Russian For Dummies

.pdf

164 Part II: Russian in Action

What did you do last night?

The easiest way to ask this question is

Chto ty dyelal vchyera vyechyerom? (shtoh tih dye-luhl fchee-rah vye- chee-ruhm; What did you do last night?; informal singular)

Chto vy dyelali vchyera vyechyerom? (shtoh vih dye-luh-lee fchee-rah vye-chee-ruhm; What did you do last night?; formal singular and plural)

When you’re talking about the past, the form of the verb you use depends on the gender and the number of people you’re addressing and the level of formality between you. (For more information, see Chapter 2.) The following are some of the forms of the verb to do that you want to be familiar with:

dyelal (dye-luhl; did/was doing; male, informal singular)

dyelala (dye-luh-luh; did/was doing; female, informal singular)

dyelali (dye-luh-lee; did/were doing; formal singular and plural)

You can answer the question Chto ty dyelal vchyera vyecherom? with

Nichyego (nee-chee-voh; nothing)

Ya byl doma (ya bihl doh-muh; I was at home) if you’re a male

Ya byla doma (ya bih-lah doh-muh; I was at home) if you’re a female If you know that the person you’re talking to was out, you can ask

Kuda ty vchyera khodil? (koo-dah tih fchee-rah khah-deel; What did you do yesterday? Literally: Where did you go yesterday?; informal singular) when speaking to a male

Kuda ty vchyera khodila? (koo-dah tih fchee-rah khah-dee-luh; What did you do yesterday? Literally: Where did you go yesterday?; informal singular) when speaking to a female

Kuda vy vchyera khodili? (koo-dah vih fchee-rah khah-dee-lee; What did you do yesterday? Literally: Where did you go yesterday?; formal singular and plural)

To answer these questions, you can say:

Ya byl v . . . (ya bihl v; I was in/at . . .) + a noun in the prepositional case if you’re a male

Ya byla v . . . (ya bih-lah v; I was in/at . . .) + a noun in the prepositional case if you’re a female

Chapter 8: Enjoying Yourself: Recreation and Sports 165

Ya khodil v . . . (ya khah-deel v; I went to . . .) + a noun in the accusative case if you’re a male

Ya khodila v . . . (ya khah-deel-luh v; I went to . . .) + a noun in the accusative case if you’re a female

If you want to specify exactly when you did something (even if it wasn’t yesterday or last night), you may want to use these phrases:

vchyera utrom (fchee-rah oot-ruhm; yesterday morning)

vchyera vyechyerom (fchee-rah vye-chee-ruhm; last night)

na proshloj nyedyelye (nuh proh-shluhy nee-dye-lee; last week)

na vykhodnyye (nuh vih-khahd-nih-ee; over the weekend)

What are you doing this weekend?

You may try to get the most out of your weeknights, but the weekend is the time for real adventure. Find out what your Russian friends do on the weekends using the following phrases:

Chto ty planiruyesh’ dyelat’ na vykhodnyye? (shtoh tih plah-nee-roo- eesh’ dye-luht’ nuh vih-khahd-nih-ee; What are you doing this weekend? Literally: What do you plan to do this weekend?; informal singular)

Chto vy planiruyetye dyelat’ na vykhodnyye? (shtoh vih plan-nee-roo- ee-tee dye-luht’ nuh vih-khahd-nih-ee; What are you doing this weekend? Literally: What do you plan to do this weekend?; formal singular and plural)

Chto ty obychno dyelayesh’ na vykhodnyye? (shtoh tih ah-bihch-nuh dye-luh-eesh’ nuh vih-khahd-nih-ee; What do you usually do on the weekend?; informal singular)

Chto vy obychno dyelayetye na vykhodnyye? (shtoh vih ah-bihch-nuh dye-luh-ee-tee nuh vih-khahd-nih-ee; What do you usually do on the weekend?; formal singular and plural)

Chto ty dyelayesh’ syegodnya vyechyerom? (shtoh tih dye-luh-eesh’ see-vohd-nye vye-chee-ruhm; What are you doing tonight?; informal singular)

Chto vy dyelayetye syegodnya vyechyerom? (shtoh vih dye-luh-ee-tee see-vohd-nye vye-chee-ruhm; What are you doing tonight?; formal singular and plural)

166 Part II: Russian in Action

To answer these questions, you may say:

Ya planiruyu (ya pluh-nee-roo-yu; I plan to . . .) + the imperfective infinitive of a verb

My planiruyem (mih pluh-nee-roo-eem; We plan to . . .) + the imperfective infinitive of a verb

Ya budu (ya boo-doo; I will . . .) + the imperfective infinitive of a verb

My budyem (mih boo-deem; We will . . .) + the imperfective infinitive of a verb

Ya obychno (ya ah-bihch-nuh; I usually . . .) + the imperfective verb in the first person singular (“I”) form

My obychno (mih ah-bihch-nuh; We usually . . .) + the imperfective verb in the first person singular (“I”) form

For details about imperfective infinitives of verbs, see Chapter 2.

And if you don’t have any particular plans, you may want to simply say Ya budu doma (ya boo-doo doh-muh; I’ll be at home) or My budyem doma (mih boo-deem doh-muh; We’ll be at home).

What do you like to do?

In conversation, you can easily switch from talking about your private life to discussing your general likes and dislikes, which Russians like to do a lot. To discover someone’s likes or dislikes, you can ask one of the following:

Chyem ty lyubish’ zanimat’sya? (chyem tih lyu-beesh’ zuh-nee-maht-sye; What do you like to do?; informal singular)

Chyem vy lyubitye zanimat’sya? (chyem vih lyu-bee-tee zuh-nee-maht- sye; What do you like to do?; formal singular and plural)

Ty lyubish’ . . . ? (tih lyu-beesh’; Do you like . . . ?; informal singular) + the imperfective infinitive of a verb or a noun in the accusative case

Vy lyubitye . . . ? (vih lyu-bee-tee; Do you like . . . ?; formal singular and plural) + the imperfective infinitive of a verb or a noun in the accusative case

For details about infinitives and cases, see Chapter 2.

You use the verb lyubit’ (lyu-beet’; to love, to like) to describe your feelings toward almost anything, from borsh’ (borsh’; borsht) to your significant other. Saying Ya lyublyu gruppu “U2” (ya lyu-blyu groo-poo yu-too; I like the band U2) isn’t too strong, and this word is just right to express your feelings for your family members, too: Ya lyublyu moyu malyen’kuyu syestru (ya lyu- blyu mah-yu mah-leen’-koo-yu sees-troo; I love my little sister).

Chapter 8: Enjoying Yourself: Recreation and Sports 167

Just like in English, the activity you like is expressed by the infinitive of a verb after the verb lyubit’: Ya lyublyu chitat’ (ya lyu-blyu chee-taht’; I like to read). With nouns, however, the rule is different. To describe a person or object you love or like, put the noun in the accusative case: Ya lyublyu muzyku (ya lyu- blyu moo-zih-koo; I love music).

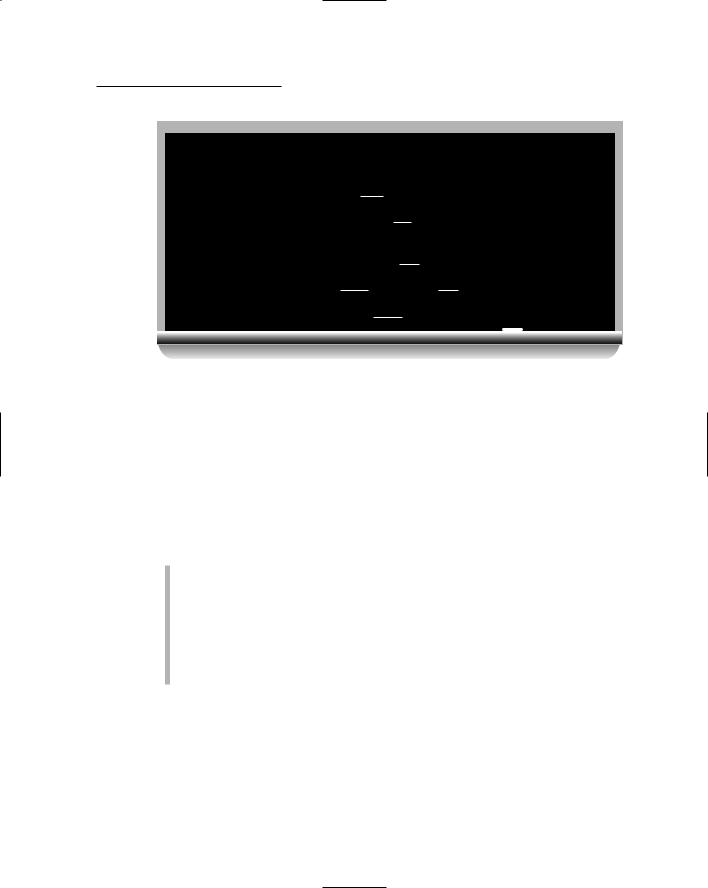

Table 8-1 shows you how to conjugate the verb lyubit’ in the present tense.

Table 8-1 |

Conjugation of Lyubit’ |

|

Conjugation |

Pronunciation |

Translation |

ya lyublyu |

yah lyu-blyu |

I love/like |

|

|

|

ty lyubish’ |

tih lyu-beesh’ |

You love/like (informal |

|

|

singular) |

|

|

|

on/ona/ono lyubit’ |

on/ah-nah/ah-noh lyu-beet’ |

He/she/it loves/likes |

|

|

|

my lyubim |

mih lyu-beem |

We love/like |

|

|

|

vy lyubitye |

vih lyu-bee-tee |

You love/like (plural singular |

|

|

and formal) |

|

|

|

oni lyubyat |

ah-nee lyu-byet |

They love/like |

|

|

|

After Russians find out what you like to do, they’re likely to come up with activities you can do together. To find out how to extend and respond to invitations, check out Chapter 7. And even if you have absolutely no interests in common, an invitation is still likely to follow: Prikhoditye v gosti! (pree-khah- dee-tee v gohs-tee; Come to visit!)

Reading All About It

An American who has traveled in Russia observed that on the Moscow metro, half the people are reading books, and the other half are holding beer bottles. But we don’t agree with such a sharp division. Some Russians can be holding a book in one hand and a beer bottle in the other!

But, all joking aside, Russians are still reported to read more than any other nation in the world. So, get prepared to discuss your reading habits using phrases we introduce in the following sections.

168 Part II: Russian in Action

Russian writers you just gotta know

A reading nation has to have some outstanding authors, and Russians certainly do. Russia is famous for the following writers:

Chekhov, or Chyekhov (cheh-khuhf) in Russian, is up there with Shakespeare and Ibsen on the Olympus of world dramaturgy. His Cherry Orchard and The Seagull are some of the most heart-breaking comedies you’ll ever see.

Dostoevsky, or Dostoyevskij (duh-stah- yehf-skee) in Russian, is the reason 50 percent of foreigners decide to learn Russian. He was a highly intense, philosophical, 19th-century writer, whose tormented and yet strangely lovable characters search for truth while throwing unbelievably scandalous scenes in public places. “The Grand Inquisitor’s Monologue” from his Brothers

Karamazov is probably the most frequently cited “favorite literary passage” among politicians all over the world.

Pushkin, or Pushkin (poosh-keen) in Russian, is someone you can mention if you want to soften any Russian’s heart. Pushkin did for Russian what Shakespeare did for English, and thankful Russians keep celebrating his birthday and putting up more and more of his statues in every town.

Tolstoy, or Tolstoj (tahl-stohy) in Russian, was a subtle psychologist and connoisseur of the human soul. His characters are so vivid, you seem to know them better than you do your family members. Reading Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina or War and Peace is the best-discovered equivalent of living a lifetime in 19th-century Russia.

Have you read it?

When you talk about reading, a handy verb to know is chitat’ (chee-taht’; to read). This verb is a regular verb (see Chapter 2 for more information). Here are some essential phrases you need in a conversation about reading:

Ya chitayu . . . (ya chee-tah-yu; I read/am reading . . .) + a noun in the accusative case

Chto ty chitayesh’? (shtoh tih chee-tah-eesh’; What are you reading?; informal singular)

Chto vy chitayetye? (shtoh vih chee-tah-ee-tee; What are you reading?; formal singular and plural)

Ty chital . . . ? (tih chee-tahl; Have you read . . . ?; informal singular) + a noun in the accusative case when speaking to a male

Ty chitala . . . ? (tih chee-tah-luh; Have you read . . . ?; informal singular) + a noun in the accusative case when speaking to a female

Vy chitali . . . ? (vih chee-tah-lee; Have you read . . . ?; formal singular and plural) + a noun in the accusative case

Chapter 8: Enjoying Yourself: Recreation and Sports 169

What do you like to read?

So you’re ready to talk about your favorite kniga (knee-guh; book) or knigi (knee-gee; books). Here are some words to outline your general preferences in literature, some of which may sound very familiar:

lityeratura (lee-tee-ruh-too-ruh; literature)

proza (proh-zuh; prose)

poyeziya (pah-eh-zee-ye; poetry)

romany (rah-mah-nih; novels)

povyesti (poh-vees-tee; tales)

rasskazy (ruhs-kah-zih; short stories)

p’yesy (p’ye-sih; plays)

stikhi (stee-khee; poems)

The conversation probably doesn’t end with you saying Ya lyublyu chitat’ romany (ya lyu-blyu chee-taht’ rah-mah-nih; I like to read novels). Somebody will ask you: A kakiye romany vy lyubitye? (ah kuh-kee-ee rah-mah-nih vih lyu-bee-tee; And what kind of novels do you like?) To answer this question, you can simply say Ya lyublyu (ya lyu-blyu; I like . . .) plus one of the following genres:

sovryemyennaya proza (suhv-ree-mye-nuh-ye proh-zuh; contemporary fiction)

dyetyektivy (deh-tehk-tee-vih; mysteries)

trillyery (tree-lee-rih; thrillers)

boyeviki (buh-ee-vee-kee; action novels)

vyestyerny (vehs-tehr-nih; Westerns)

istorichyeskaya proza (ees-tah-ree-chees-kuh-ye proh-zuh; historical fiction)

fantastika (fuhn-tahs-tee-kuh; science fiction)

lyubovnyye romany (lyu-bohv-nih-ee rah-mah-nih; romance)

biografii (bee-ahg-rah-fee-ee; biographies)

istorichyeskiye isslyedovaniya (ees-tah-ree-chees-kee-ee ees-lye-duh- vuh-nee-ye; history, Literally: historical research)

myemuary (meh-moo-ah-rih; memoirs)

170 Part II: Russian in Action

Many Russian last names, like the famous Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, decline like adjectives. Even in their initial form, in the nominative case, they sound similar. When you talk about works by a specific author, you put the name of the author in the genitive case, and place it after the word knigi (knee-gee; books): knigi Pushkina (knee-gee poosh-kee-nuh; books by Pushkin). The genitive case conveys the meaning “belonging to someone, pertaining to someone, of someone.” Examples include: p’yesy Shyekspira (p’ye-sih shehk- spee-ruh; Shakespeare’s plays), and rasskazy Chekhova (ruhs-kah-zih cheh- khuh-vuh; short stories by Chekhov). For more on cases, see Chapter 2.

Now you’re well-prepared to talk about literature, but what about the news, political commentary, and celebrity gossip? These phrases can help:

zhurnal (zhoor-nahl; magazine)

gazyeta (guh-zye-tuh; newspaper)

novosti (noh-vuhs-tee; the news)

novosti v intyernyetye (noh-vuhs-tee v een-tehr-neh-tee; news on the Internet)

stat’ya (stuh-t’ya; article)

komiksy (koh-meek-sih; comic books)

Talkin’ the Talk

It’s Claire’s first time in a Russian library. A friendly bibliotekar’ (beeb-lee-ah-tye-kuhr’; librarian) starts a conversation.

Bibliotekar’: Vy lyubitye chitat’?

|

vih lyu-bee-tee chee-taht’? |

|

Do you like to read? |

Claire: |

Da, ochyen’ lyublyu. Osobyenno romany. |

|

dah, oh-cheen’ lyu-blyu. ah-soh-bee-nuh rah-mah-nih. |

|

Yes, I like it very much. Especially novels. |

Bibliotekar’: A kakie romany, istorichyeskiye ili dyetyektivy?

ah kuh-kee-ee rah-mah-nih, ees-tah-ree-chees-kee-ee ee-lee deh-tehk-tee-vih?

And what kind of novels, historical or mysteries?

Claire: |

Bol’shye vsyego ya lyublyu fantastiku. |

|

bohl’-sheh vsee-voh ya lyu-blyu fuhn-tahs-tee-koo. |

|

Most of all, I like science fiction. |

|

|

Chapter 8: Enjoying Yourself: Recreation and Sports 171

Words to Know

osobyenno |

ah-soh-bee-nuh |

especially |

istorichyeskiye |

ees-tah-ree- |

historical |

|

chees-kee-ee |

|

dyetyektivy |

deh-tehk-tee-vih |

mystery |

bol’she vsego |

bohl’-sheh vsee-voh |

most of all |

fantastika |

fuhn-tahs-tee-kah |

science fiction |

Where do you find reading materials?

The answer to where you can find reading material is easy: Pretty much anywhere. At a Russian train station, you’re likely to see more book and periodical stands than hot dog vendors. They won’t offer the best choices, though, unless you’re looking for dyetyektivy (deh-tehk-tee-vih; mystery novels) or boyeviki (buh-ee-vee-kee; action novels). For more serious literature, you have to go to knizhnij magazin (kneezh-nihy muh-guh-zeen; bookstore) or bibliotyeka (beeb-lee-ah-tye-kuh; library). Both bookstores and libraries are divided into otdyely (aht-dye-lih; sections):

Otdyel khudozhyestvyennoj lityeratury (aht-dyel khoo-doh-zhihs-tvee- nuhy lee-tee-ruh-too-rih; section of fiction)

Otdyel uchyebnoj lityeratury (aht-dyel oo-chyeb-nuhy lee-tee-ruh-too- rih; section of educational materials)

Spravochnyj otdyel (sprah-vuhch-nihy aht-dyel; reference section)

Otdyel audio i vidyeo matyerialov (aht-dyel ah-oo-dee-uh ee vee-dee-uh muh-tee-r’ya-luhf; audio and video section)

Rejoicing in the Lap of Nature

Russians love nature. Every city in Russia has big parks where numerous urban dwellers take walks, enjoy picnics, and swim in suspiciously smelling ponds. Even more so, Russians like to get out of town and enjoy the nature in the wild. Luckily, the country’s diverse geography offers a wide variety of

172 Part II: Russian in Action

opportunities to do so. In the following sections, you discover how to make the most out of enjoying nature in Russian.

Enjoying the country house

The easiest route to nature is through the dacha (dah-chuh), which is a little country house not far from the city that most Russians have. Poyekhat’ na dachu (pah-ye-khuht’ nuh dah-choo; to go to the dacha) usually implies an overnight visit that includes barbecuing, dining in the fresh air, and, if you’re lucky, banya (bah-nye) — the Russian-style sauna. Some phrases to use during your dacha experience include the following:

zharit’ shashlyk (zhah-reet’ shuh-shlihk; to barbecue)

razvodit’ kostyor (ruhz-vah-deet’ kahs-tyor; to make a campfire)

natopit’ banyu (nuh-tah-peet’ bah-nyu; to prepare the sauna)

sad (saht; orchard, garden)

ogorod (uh-gah-roht; vegetable garden)

sobirat’ ovosh’i (suh-bee-raht’ oh-vuh-sh’ee; to pick vegetables)

rabotat’ v sadu (ruh-boh-tuht’ f suh-doo; to garden)

Picking foods in the forest

With their 73 percent of urban population, Russians like to go back to their roots and experience the kind of life where, instead of going to a store, you actually have to wander through the woods to find your food. Apparently, plenty of edible stuff is growing in the lyes (lyes; forest), and finding it is a fun activity similar to collecting points in a computer game. Just make sure to find out what you’re about to eat before you put it in your mouth!

Things you may find in the forest include:

s’yedobniye griby (s’ee-dohb-nih-ee gree-bih; edible mushrooms)

nyes’yedobniye griby (nee-s’ee-dohb-nih-ee gree-bih; poisonous mushrooms)

yagody (ya-guh-dih; berries)

dyeryevo (dye-ree-vuh; tree)

dyeryev’ya (dee-ryev’-ye; trees)

travy (trah-vih; herbs)

Chapter 8: Enjoying Yourself: Recreation and Sports 173

To talk about collecting any or all of the foods in this section, use the verb sobirat’ (suh-bee-raht’; to pick, to collect).

To describe your trip to the forest, use the expression khodit’ v lyes (khah- deet’ v lyes; to hike in the woods). And if your hiking trip involves a kostyor (kahs-tyor; campfire) and a palatka (puh-laht-kuh; tent), you can use the expression idti v pokhod (ee-tee f pah-khoht; to go camping).

Skiing in the Caucasus

The Caucasus, a picturesque mountainous region in the South of Russia, is easily accessible by train or by a flight into the city of Minvody, which actually stands for minyeral’niye vody (mee-nee-rahl’-nih-ee voh-dih; mineral waters). The reason for this unusual name is the numerous spas scattered around this beautiful area. Mineral water-based sanatorii (suh-nuh-toh-ree-ee; health care spas) and doma otdykha (dah-mah oht-dih-khuh; resorts) promise a cure for almost any health problem.

The best places to ski in the Caucasus (called Kavkaz in Russian) include Dombaj (dahm-bahy) and Priyel’brus’ye (pree-ehl’-broo-s’ee). The word Priel’brus’ye actually means “next to El’brus,” with El’brus (ehl’-broos) being the highest mountain peak in Europe (according to those who consider the Caucasus a part of Europe).

Here are some phrases to help you organize your skiing adventure:

gora (gah-rah; mountain)

gory (goh-rih; mountains)

lyzhi (lih-zhih; skis)

snoubord (snoh-oo-bohrd; snowboard)

katat’sya na lyzhakh (kuh-taht’sye nuh lih-zhuhkh; to ski)

prokat (prah-kaht; rental)

vzyat’ na prokat (vzyat’ nuh prah-kaht; to rent)

kanatnaya doroga (kuh-naht-nuh-ye dah-roh-guh; cable cars)

kanatka (kuh-naht-kuh; cable cars)

turbaza (toor-bah-zuh; tourist center)

kryem ot zagara (krehm uht zuh-gah-ruh; sunblock)