Russian For Dummies

.pdf

154 Part II: Russian in Action

To ask for a ticket, customers often use a kind of a stenographic language. Kassiry (kuh-see-rih; cashiers) are generally impatient people, and you may have a line behind you. So try to make your request for a ticket as brief as you can. If you want to go to the 2:30 p.m. show, you say one of these phrases:

Odin na chyetyrnadtsat’ tridtsat’ (ah-deen nah chee-tihr-nuh-tsuht’ treet- tsuht’; One for 2:30)

Dva na chyetyrnadtsat’ tridtsat’ (dvah nah chee-tihr-nuh-tsuht’ treet- tsuht’; Two for 2:30)

Because probably only one movie will be showing at that time, the kassir (kuh-seer; cashier) will know which movie you want to see. But if two movies happen to be showing at the same time, or if you want to make sure that you get tickets to the right movie, you can simply add the phrase na (nah; to) plus the title of the movie to your request.

Choosing a place to sit and watch

In Russia, when you buy a ticket to the movie, you’re assigned a specific seat, so the kassir (kuh-seer; cashier) may ask you where exactly you want to sit. You may hear Gdye vy khotitye sidyet’? (gdye vih khah-tee-tee see-dyet’; Where do you want to sit?) or Kakoj ryad? (kuh-kohy ryat; Which row?)

The best answer is V syeryedinye (f see-ree-dee-nee; in the middle). If you’re far-sighted, you may want to say Podal’shye (pah-dahl’-sheh; further away from the screen). But if you want to sit closer, you say Poblizhye (pah-blee- zheh; closer to the screen). You may also specify a row by saying pyervyj ryad (pyer-viy ryat; first row) or vtoroj ryad (vtah-roy ryat; second row). See Chapter 2 for more about ordinal numbers.

When you finally get your ticket, you must be able to read and understand what it says. Look for the words ryad (ryat; row) and myesto (myes-tuh; seat). For example, you may see Ryad: 5, Myesto: 14. That’s where you’re expected to sit!

In the following sections, we cover two handy verbs to know at the movies: the verbs “to sit” and “to watch.”

The verb “to sit”

The verb sidyet’ (see-dyet’; to sit) has a very peculiar conjugation; the d changes to zh in the first person singular. Because you’ll use this verb a lot, it’s a good idea to have the full conjugation. Check out Table 7-1.

Chapter 7: Going Out on the Town, Russian-Style 155

Table 7-1 |

Conjugation of Sidyet’ |

|

Conjugation |

Pronunciation |

Translation |

ya sizhu |

ya see-zhoo |

I sit or I am sitting |

|

|

|

ty sidish’ |

tih see-deesh |

You sit or You are sitting |

|

|

(informal singular) |

on/ona/ono sidit |

ohn/ah-nah/ah-noh see-deet |

He/she/it sits or He/she/it is |

|

|

sitting |

|

|

|

my sidim |

mih see-deem |

We sit or We are sitting |

|

|

|

vy siditye |

vih see-dee-tee |

You sit or You are sitting |

|

|

(formal singular and plural) |

|

|

|

oni sidyat |

ah-nee see-dyat |

They sit or They are sitting |

|

|

|

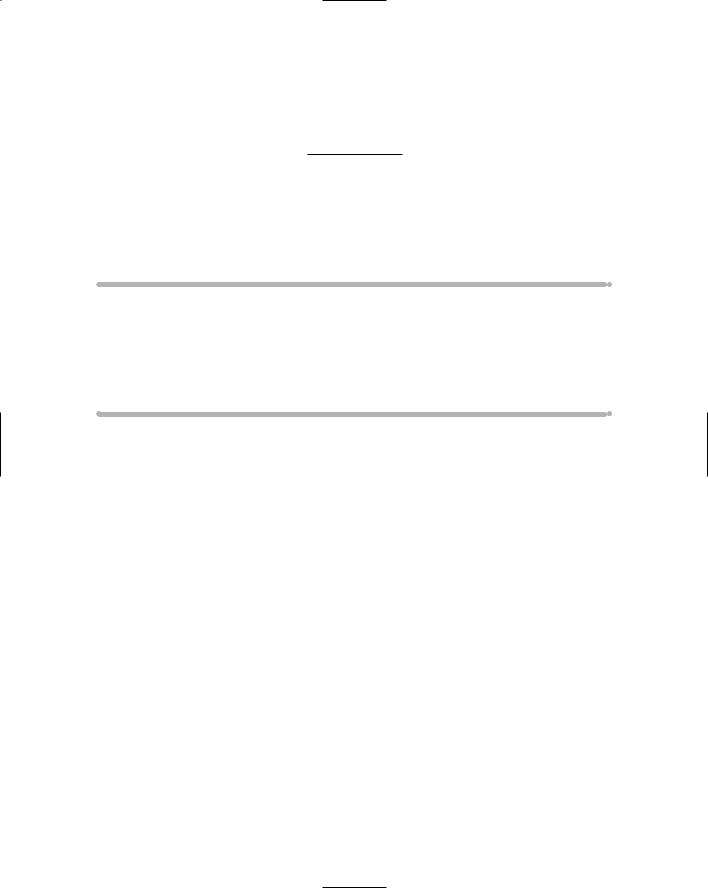

The verb “to watch”

The verb smotryet’ (smah-tret’; to watch) is another useful word when you go to the movies. Table 7-2 shows how you conjugate it in the present tense.

Table 7-2 |

Conjugation of Smotryet’ |

|

Conjugation |

Pronunciation |

Translation |

ya smotryu |

ya smah-tryu |

I watch or I am watching |

|

|

|

ty smotrish’ |

tih smoht-reesh |

You watch or You are watching |

|

|

(informal singular) |

|

|

|

on/ona/ono smotrit |

ohn/ah-nah/ah-noh |

He/she/it watches or He/she/it is |

|

smoht-reet |

watching |

|

|

|

my smotrim |

mih smoht-reem |

We watch or We are watching |

|

|

|

vy smotritye |

vih smoht-ree-tee |

You watch or You are watching |

|

|

(formal singular and plural) |

oni smotryat |

ah-nee smoht-ryet |

They watch or They are watching |

|

|

|

156 Part II: Russian in Action

It’s Classic: Taking in the Russian

Ballet and Theater

If a Russian ballet company happens to be in your area, don’t miss it! And if you’re in Russia, don’t even think of leaving without seeing at least one performance either in Moscow’s Bol’shoy Theater or St. Petersburg’s Mariinski Theater. No ballet in the world can compare with the Russian balyet (buh- lyet; ballet) in its grand, powerful style, lavish decor, impeccable technique, and its proud preservation of the classical tradition.

The Russian teatr (tee-ahtr; theater) is just as famous and impressive as the ballet, but most theater performances are in Russian, so you may not understand a lot until you work on your Russian for a while. Still, if you want to see great acting and test your Russian knowledge, by all means check out the theater, too!

In the following sections, we show how to get your tickets and what to do during the intermission.

Handy tips for ordering tickets

The technique of buying a ticket to the ballet or theater is basically the same as it is for the movie theater. Each performance hall has a kassa (kah-suh; ticket office) and a kassir (kuh-seer; cashier). You may hear Gdye vy khotitye sidyet’? (gdye vih khah-tee-tee see-dyet’; Where do you want to sit?) or Kakoj ryad? (kah-kohy ryat; Which row?) See the sections “Buying tickets” and “Choosing a place to sit and watch” earlier in this chapter.

Your answer to this question is a little bit different than in a movie theater. If you prefer a centrally located seat, you say V partyerye (f puhr-teh-ree; In the orchestra seats). But a Russian ballet hall is more complicated than a movie theater, and it has many other seating options you may want to consider, depending on your budget and taste:

lozha (loh-zhuh; box seat)

byenuar (bee-noo-ahr; lower boxes)

byel’etazh (behl’-eh-tahsh; tier above byenuar)

yarus (ya-roos; tier above bel’ehtazh)

galyeryeya (guh-lee-rye-ye; the last balcony)

balkon (buhl-kohn; balcony)

Chapter 7: Going Out on the Town, Russian-Style 157

You can try your luck at ordering tickets over the phone too. If you’re lucky enough to have somebody pick up the phone when you call the ticket office, and you’re a male, you say Ya khotyel by zakazat’ bilyet na . . . (ya khah-tyel bih zuh-kuh-zaht’ bee-lyet nah; I would like to order a ticket for . . .) + the name of the performance. If you’re a female, you say Ya khotyela by zakazat’ bilyet na . . . (ya khah-tye-luh bih zuh-kuh-zaht’ bee-lyet nah; I would like to order a ticket for . . .) + the name of the performance.

Next, you most likely hear Na kakoye chislo? (nah kah-koh-ee chees-loh; For what date?) Your response should begin with na (nah; for) followed by the date you want to attend the performance, such as Na pyatoye maya (nuh pya-tuh-ye mah-ye; For May 5). You can also say things like na syegodnya (nah see-vohd-nye; for today) or na zavtra (nuh zahf-truh; for tomorrow). And if you want to buy a ticket for a specific day of the week, you say na plus the day of the week in the accusative case. For example, “for Friday” is na pyatnitsu (nuh pyat-nee-tsoo; for Friday).

When you indicate a date, use the ordinal number and the name of the month in the genitive case. For more information on ordinal numerals, see Chapter 2. For information on months, see Chapter 11.

Things to do during the intermission

During the antrakt (uhn-trahkt; intermission), we recommend that you take a walk around the koridor (kuh-ree-dohr; hall) and look at the pictures of the past and current aktyory (uhk-tyo-rih; actors), aktrisy (uhk-tree-sih; actresses), balyeriny (buh-lee-ree-nih; ballerinas), and rezhissyory (ree-zhih-syo-rih; theater directors) that are usually displayed. Another thing you may want to do is grab a bite to eat at the bufyet (boo-fyet; buffet), which is designed to make you feel that coming to the theater is a very special occasion. Typical buffet delicacies are butyerbrody s ikroj (boo-tehr-broht s eek-rohy; caviar sandwiches), butyerbrody s kopchyonoj ryboj (boo-tehr-broht s kuhp-chyo-nuhy rih-buhy; smoked fish sandwiches), pirozhnyye (pee-rohzh-nih-ee; pastries), shokolad (shuh-kah- laht; chocolate), and shampanskoye (shuhm-pahn-skuh-ee; champagne).

Spectators aren’t allowed to wear overcoats, raincoats, or hats in the seating area. Theater-goers are expected to leave street clothing in the gardyerob (guhr-dee-rohp; cloakroom). Marching into a seating area with your coat or hat on may anger the theater attendants, who won’t hesitate to express it to you quite loudly in public.

158 Part II: Russian in Action

Enjoying (or just plain surviving) the Philharmonic

Are you a classical music lover? If so, then the Russian Philharmonic may be just what you’re looking for. But if not, then we recommend you try to avoid the Philharmonic, even if tickets are free. If you’re not used to classical music or if you can tolerate it only in limited amounts of time, going to the Philharmonic may be a very trying experience. For one thing, you have to sit almost motionless for over two hours, staring at the orkyestr (ahr-kyestr; the orchestra) or ispolnityel’ (ees-pahl-nee-teel’; performer/soloist).

Secondly, you’re not allowed to talk with your friend sitting next to you, eat candy, chew gum, or produce any sound that may disturb your fellow music lovers.

When you’re at the Philharmonic, you’re expected to do one thing and one thing only: slushat’ muzyku! (sloo-shuht’ moo-zih-koo; to listen to the music!) Whether you actually hear the music is up to you!

Culture Club: Visiting a Museum

Russians are a nation of museum-goers. Visiting a myzyej (moo-zyey; museum) is seen as a “culture” trip. This view explains why Russian parents consider their first duty to be taking their kids to all kinds of museums on a weekend. Apart from the fact that Russian cities and even villages usually have a lot of museums, whenever Russians go abroad they immediately start looking for museums they can go to. A trip anywhere in the world should certainly contain a number of museums.

In almost every city you’re likely to find the following museums to satisfy your hunger for culture:

Muzyej istorii goroda (moo-zyey ees-toh-ree-ee goh-ruh-duh; museum of the town history)

Muzyej istorii kraya (moo-zyey ees-toh-ree-ee krah-ye; regional history museum)

Istorichyeskij muzyej (ee-stah-ree-chees-keey moo-zyey; historical museum)

Kartinnaya galyeryeya (kuhr-tee-nuh-ye guh-lee-rye-ye; art gallery)

Etnografichyeskij muzyej (eht-nuh-gruh-fee-chees-keey moo-zyey; ethnographic museum)

Also, you may want to visit any of the large number of Russian museums dedicated to famous and not so famous Russian pisatyeli (pee-sah-tye-lee; writers), poety (pah-eh-tih; poets), aktyory (uhk-tyo-rih; actors) and aktrisy

Chapter 7: Going Out on the Town, Russian-Style 159

(uhk-tree-sih; actresses), khudozhniki (khoo-dohzh-nee-kee; artists), uchyonyye (oo-choh-nih-ee; scientists), and politiki (pah-lee-tee-kee; politicians). For example, in St. Petersburg alone, you find the A.S. Pushkin museum, F.M. Dostoyevsky museum, A.A. Akhmatova museum, and many, many more — almost enough for every weekend of the year.

In addition to the previously listed museums, you should also know that a lot of former tsar residences were converted into museums by the special decree of the new Soviet government after the October revolution of 1917. At that time, one of the main purposes of this action was to show the working people of Russia the revolting luxury the former Russian rulers lived in by exploiting their people. A lot of these museums are in St. Petersburg and its vicinity. Four of the most popular are Zimnyj Dvoryets (zeem-neey dvah-ryets; Winter Palace), Lyetnij Dvoryets Pyetra Vyelikogo (lyet-neey dvah-ryets peet-trah vee-lee-kuh-vuh; Summer Palace of Peter the Great), Yekatirininskij Dvoryets (yee-kuh-tee-ree-neens-skeey dvah-ryets; Catherine’s Palace), and Pavlovskij Dvoryets (pahv-luhf-skeey dvah-ryets; Paul’s Palace).

Some other words and expressions you may need in a museum are

ekskursiya (ehks-koor-see-ye; tour)

ekskursovod (ehks-koor-sah-voht; guide)

ekskursant (ehks-koor-sahnt; member of a tour group)

putyevodityel’(poo-tee-vah-dee-teel’; guidebook)

zal (zahl; exhibition hall)

eksponat (ehks-pah-naht; exhibit)

vystavka (vihs-tuhf-kuh; exhibition)

ekspozitsiya (ehks-pah-zee-tsih-ye; display)

iskusstvo (ees-koos-tvuh; arts)

kartina (kuhr-tee-nuh; painting)

skul’ptura (skool’-ptoo-ruh; sculpture or piece of sculpture)

Muzyyej otkryvayetsya v . . . (moo-zyey uht-krih-vah-eet-sye v; The museum opens at . . .)

Muzyyej zakryvayetsya v . . . (moo-zyey zuh-krih-vah-eet-sye v; The museum closes at . . .)

Skol’ko stoyat vkhodnyye bilyety? (skohl’-kuh stoh-eet fkhahd-nih-ee bee-lye-tih; How much do admission tickets cost?)

160 Part II: Russian in Action

How Was It? Talking about

Entertainment

After you’ve been out to the ballet, theater, museum, or a movie, you probably want to share your impressions with others. The best way to share these impressions is by using a form of the verb nravitsya (nrah-veet-sye; to like).

(For details on the present tense of this verb, see Chapter 6.) To say that you liked what you saw, you may want to say Mnye ponravilsya spyektakl’/fil’m (mnye pahn-rah-veel-sye speek-tahkl’/feel’m; I liked the performance/movie).

If you didn’t like the production, just add the particle nye before the verb:

Mnye nye ponravilsya spyektakl’/fil’m (mnye nee pahn-rah-veel-sye speek- tahkl’/feel’m; I did not like the performance/movie).

If you really loved a museum you visited, you say Mnye ochen’ ponravilsya muzyej (mnye oh-cheen’ pahn-rah-veel-sye moo-zyey; I loved the museum).

Don’t use lyubil (lyu-beel; loved) in this situation. The past tense of the verb lyubit’ (lyu-beet’; to love) means “I used to love,” which isn’t exactly what you want to say here. To read more about the verb lyubit’, see Chapter 8.

If you want to elaborate on your opinion about the performance or museum, you may want to use words and phrases like

potryasayush’ye! (puh-tree-sah-yu-sh’ee; amazing!)

khoroshii balyet/spyektakl’/kontsyert (khah-roh-shihy buh-lyet/speek- tahkl’/kahn-tsehrt; a good ballet/performance/concert)

plokhoj balyet/spyektakl’/fil’m (plah-khohy buh-lyet/speek-tahkl’/feel’m; a bad ballet/performance/film)

Eto byl ochyen’ krasivyj balyet/spyektakl’/muzyej. (eh-tuh bihl oh- cheen’ krah-see-vihy buh-lyet/speek-tahkl’/moo-zyey; It was a very beautiful ballet/performance/museum.)

Eto byl ochyen’ skuchnyj fil’m/spyektakl’/myzyej. (eh-tuh bihl oh- cheen’ skoosh-nihy feel’m/speek-tahkl’/moo-zyey; It was a very boring film/performance/museum.)

Eto byl nyeintyeryesnyj fil’m/spyektakl’/muzyej. (eh-tuh bihl nee-een- tee-ryes-nihy feel’m/speek-tahkl’/ moo-zyey; It wasn’t an interesting film/performance/museum.)

To ask a friend whether he or she liked an event, you can say Tyebye ponravilsya spyektakl/fil’m’? (tee-bye pahn-rah-veel-sye speek-tahkl’/feel’m?; Did you like the performance/movie?)

Chapter 7: Going Out on the Town, Russian-Style 161

Talkin’ the Talk

Natasha and John have just attended a classical ballet at the St. Petersburg Mariinskij Theater. As they’re leaving the theater, they exchange their opinions of the performance.

Natasha: |

Tyebye ponravilsya spyektakl’? |

|

tee-bye pahn-rah-veel-sye speek-tahkl’? |

|

Did you like the performance? |

John: |

Ochyen’. Potryasayush’ye. Ochyen’ krasivyj balyet. |

|

A tyebye? |

|

oh-cheen’. puh-tree-sah-yu-sh’ee. oh-cheen’ kruh-see- |

|

vihy buh-lyet uh tee-bye? |

|

A lot. It was amazing. Very beautiful ballet. And did |

|

you like it? |

Natasha: |

I mnye ochyen’ ponravilsya etot spyektakl’. Solistka |

|

tantsyevala ochyen’ khorosho. I dyekoratsii byli |

|

pryekrasnyye. |

|

ee mnye oh-cheen’ pahn-rah-veel-sye. sah-leest-kuh |

|

tuhn-tseh-vah-luh oh-cheen’ khuh-rah-shoh. ee dee- |

|

kah-rah-tsih-ee bih-lee pree-krahs-nih-ee |

|

And I liked the performance a lot. The soloist danced |

|

very well. And the décor was wonderful. |

|

|

Words to Know

A tyebye? |

a tee-bye |

And did you |

|

|

like it? |

solistka |

sah-leest-kuh |

soloist |

ochyen’ khorosho |

oh-cheen’ khuh- |

very good/well |

|

rah-shoh |

|

dyekoratsii |

dee-kah-raht-tsee-ee décor |

|

pryekrasnyye |

preek-rahs-nih-ee |

wonderful |

162 Part II: Russian in Action

Fun & Games

Fun & Games

Which of the following two days comes earlier during a week? Check out the correct answers in Appendix C.

1.ponyedyel’nik, sryeda

2.chyetvyerg, pyatnitsa

3.voskryesyen’ye, vtornik

4.subbota, voskryesyen’ye

Which of the two verbs — nachinayetsya or nachinayet — do you use to translate the verb “to start/to begin” in the following sentences? Check out the correct answers in Appendix C.

1.Peter begins his working day at 5 a.m.

2.The show begins at 7 p.m.

3.Dinner begins at 6 p.m.

4.The boss always begins the meeting on time.

Which of the following phrases would you probably use to express that you liked the show or performance you attended? Find the correct answers in Appendix C.

1.Mnye ponravilsya spyektakl’.

2.Potryasayush’ye!

3.Ochyen’ skuchnyj fil’m.

4.Nyeintyeryesnyj fil’m.

5.Ochyen’ krasivyj balyet.

Chapter 8

Enjoying Yourself: Recreation

and Sports

In This Chapter

Discussing your hobbies

Reading everything from detectives to Dostoevsky

Enjoying nature

Collecting things, working with your hands, and playing sports

The art of conversation isn’t a forgotten skill among Russians. They love trading stories, relating their experiences, and exchanging opinions. And

what’s a better conversation starter than asking people about things they like to do? Go ahead and tell your new acquaintances about your sports obsession, your reading habits, or your almost complete collection of Star Wars action figures. In this chapter, we show you how to talk about your hobbies. You also discover some activities that Russians especially enjoy, and find out what to say when you’re participating in them.

Shootin’ the Breeze about Hobbies

Before getting to the nitty-gritty of your khobbi (khoh-bee; hobby or hobbies — the word is used for both singular and plural forms), you probably want to test the water so that you don’t exhaust your vocabulary of Russian exclamations discussing Tchaikovsky with someone who prefers boxing. In the following sections, you find out how to talk about your recent experiences, your plans for the weekend, and your general likes and dislikes.