- •Preface

- •Contents

- •List of Contributors

- •1. Introduction

- •1. CONSUMER LAW: THE GROWTH OF THE LEGISLATIVE ACQUIS

- •2. EC ADVERTISING LAW

- •4. NEW RULES AND NEW TECHNIQUES—AND NEW CHALLENGES

- •2. The Unfair Commercial Practices Directive and its General Prohibition

- •1. INTRODUCTION

- •2. THE SCOPE (ARTICLE 3)

- •3. INTERNAL MARKET (ARTICLE 4)

- •4. THE STRUCTURE

- •5. THE GENERAL PROHIBITION (ARTICLE 5)

- •7. ENFORCEMENT

- •8. CONCLUSIONS

- •1. SOME BASIC FEATURES

- •2. REDUCED OR RAISED LEVEL OF CONSUMER PROTECTION?

- •5. WILL FULL HARMONISATION BE ACHIEVED?

- •1. INTRODUCTION

- •3. THE FRAGMENTATION OF COMMUNITY RULES ON COMMERCIAL PRACTICES PRIOR TO THE UCPD

- •5. THE IMPACT OF ENLARGEMENT

- •6. DISENTANGLING THE LOGIC OF COMMUNITY INFLUENCE

- •7. THE UCPD AND ITS PROSPECTIVE EFFECTS ON CEE UNFAIR COMMERCIAL PRACTICES LAW: COHERENCE AT LAST?

- •1. INTRODUCTION

- •2. LEGAL BASIS

- •3. GENERAL CHARACTER OF EC CONSUMER PROTECTION RULES

- •5. FUTURE APPROACH OF THE COURT OF JUSTICE

- •6. CONCLUSION

- •1. INTRODUCTION

- •2. SOME CRITICISMS

- •3. POLICY DEBATES ON MAXIMAL HARMONISATION

- •4. THE INTERNAL MARKET CLAUSE

- •5. CONCLUSION

- •1. INTRODUCTION

- •2. THE VISION OF THE CONSUMER IN EC LAW—CONSTITUTIONAL INHIBITIONS TO THE DISCOVERY OF REGULATORY COHERENCE

- •5. THE ‘AVERAGE CONSUMER’ UNDER THE UCPD

- •6. CONCLUSION

- •8. The Relationship of the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive to European and National Contract Laws

- •1. INTRODUCTION

- •3. POSSIBLE INFLUENCES OF THE UCPD ON ‘CONTRACT LAW’

- •5. CONCLUSION

- •9. The Unfair Commercial Practices Directive and its Consequences for the Regulation of Sales Promotion and the Law of Unfair Competition

- •1. INTRODUCTION

- •2. THE DIRECTIVE IN CONTEXT

- •3. THE CASE LAW OF THE COURT OF JUSTICE ON FREE MOVEMENT IN THE AREA OF COMMERCIAL PRACTICES

- •4. THE UNFAIR COMMERCIAL PRACTICES DIRECTIVE: B2C ONLY

- •5. THE LAW OF UNFAIR COMPETITION IN THE MEMBER STATES

- •6. NATIONAL RULES ON SALES PROMOTIONS AFTER THE UCPD

- •7. THE INFLUENCE OF ANTITRUST LAW ON THE LAW OF CONSUMER PROTECTION AND UNFAIR COMPETITION

- •8. PLEA FOR AN INTEGRATED APPROACH AT THE EC LEVEL

- •4. THE EXAMPLE OF LOOK-ALIKES

- •5. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

- •11. Unfair Commercial Practices: Stamping out Misleading Packaging

- •1. INTRODUCTION—THE THESIS OF THIS PAPER

- •3. THE COPYCAT PROBLEM

- •4. THE IMPACT ON CONSUMERS OF COPYCAT PRODUCTS

- •5. THE UNFAIR COMMERCIAL PRACTICES DIRECTIVE

- •7. THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN PUBLIC AND PRIVATE ENFORCEMENT UNDER THE DIRECTIVE

- •1. INTRODUCTION

- •3. IMPLEMENTING THE UCPD—MAIN CHALLENGES

- •4. AFFECTED LEGISLATION

- •5. TOWARDS IMPLEMENTING THE UCPD INTO UK LAW

- •6. POST-IMPLEMENTATION ISSUES

- •7. STEPS TAKEN TOWARDS IMPLEMENTATION BY THE UK

- •8. CONCLUSIONS

- •2. THE STORY BEGINS—DISTANT SHOPPING (SWEEPSTAKES I)

- •4. REGULATION 2006/2004—NATIONALISATION (VERSTAATLICHUNG) OF LAW ENFORCEMENT

- •Appendix

- •Index

20 Giuseppe B Abbamonte

some differences in the transposition laws of the Member States or in their interpretation of the Directive. For example, Article 7(3) of the Directive regulates the information that a trader must provide in advance when he makes an invitation to purchase.32 In this information, the trader has to indicate the main characteristics of product. Now, the Member States may have different views as to the main characteristics of products. For example, Member State X may issue guidelines under which the main characteristics of cars are A, B and C, while Member State Y may choose A, B, C and D. In this case, if the trader established in X addresses an invitation to purchase to consumers in Y, it will not be possible to challenge the invitation because it does not contain item D.33

4. THE STRUCTURE

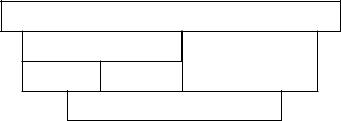

The Directive can be depicted as an inverted pyramid having the general prohibition or general clause at the apex, as illustrated in Figure 2.1.

The general prohibition is the key element of the Directive.34 It prohibits unfair commercial practices between businesses and consumers and defines the conditions for determining whether a commercial practice is unfair. In addition, the Directive regulates the main categories of unfair commercial practices: misleading and aggressive practices. The corresponding provisions reproduce with certain adaptations the tests of the general prohibition.

The general prohibition has an autonomous regulatory function in the sense that a practice which is neither misleading nor aggressive can still be captured by the general prohibition if it meets its criteria. In practice, most unfair practices are either misleading or aggressive, and it is expected that they will be assessed under these more specific provisions. The autonomous functioning of the general prohibition means that it serves as a safety net

G E N E R A L C L A U S E

MISLEADING PRACTICES

AGGRESSIVE

PRACTICES

ACTIONS OMISSIONS

B L A C K L I S T

Figure 2.1 The Structure of the Directive

32Art 7(3) of the Directive, above n 2.

33This case is further discussed in the section on the average consumer below.

34Art 5 of the Directive, above n 2.

The UCPD and its General Prohibition 21

to catch any current or future practices that cannot be categorised as either misleading or aggressive. The primary motivation is to ensure that the Directive is future-proof.

Consumer protection enforcers around the world are coming across different commercial practices in the Internet-based economy that can be defined only with great difficulty as misleading or aggressive but are equally unfair. An example of this is modem hijacking, which consists of rerouting

Internet modem connections in a way that causes the consumer to pay disproportionate telephone bills. An Internet user clicks on a banner to run a program on his computer and, without alerting the consumer, the program disconnects his modem from the local server and reconnects it to a distant server. This results in higher telephone fees compared with ordinary dial-up Internet connections. Another example of a commercial practice that could be covered under the general prohibition is given below.35

Finally, the Directive contains an exhaustive blacklist of practices that will be regarded in all circumstances as unfair.36 These unquestionably unfair practices will be prohibited at the outset in all Member States. Of course, a number of practices not explicitly included in the list could also be unfair. These practices will have to be assessed under the provisions on misleading and aggressive practices as well as those of the general prohibition. The blacklist is an integral part of the Directive and can be amended only by a revision of the Directive by means of the legislative procedure under Article 251 of the EU Treaty. The list has to be implemented in the same or an equivalent way by the Member States, which are prevented from adding to the list. If the Member States were allowed to do so, this could have the effect of circumventing the maximum harmonisation introduced by the Directive and would frustrate the objective of legal certainty pursued by the Directive.

5. THE GENERAL PROHIBITION (ARTICLE 5)

The general prohibition contains two conditions for determining whether a practice is unfair. These conditions are cumulative:

(1)The practice must be contrary to the requirements of professional diligence, and

35See below on the autonomy of the general clause.

36See Annex 1: ‘Commercial Practices which are in all circumstances considered unfair’, of the Directive, above n 3. Examples of these practices are:

—claiming to be a signatory to a code when the trader is not;

—displaying a trust mark, quality mark or equivalent without having obtained the necessary authorisation;

—creating the impression that the consumer cannot leave the premises until a contract is formed.

22Giuseppe B Abbamonte

(2)The practice must materially distort or be likely materially to distort the economic behaviour of the average consumer whom it reaches or to whom it is addressed or of the average member of the group in cases where a commercial practice is directed at a particular group of consumers.37

(a) Professional Diligence

Article 2(h) defines professional diligence as ‘the standard of special skill and care which a trader may reasonably be expected to exercise towards consumers, commensurate with honest market practice and/or the general principle of good faith in the trader’s field of activity’.38 The concept of professional diligence is broader than subjective good faith since it encompasses not only honesty but also competence on the part of the trader. For example, the behaviour of an honest but incompetent antique dealer who sells fakes, believing them to be originals, would not be in conformity with the requirements of professional diligence.

Professional diligence is broadly equivalent to the common law concept of duty of care. It is a measure of the diligence that a good businessman can reasonably be expected to exercise and must be commensurate with the duty to be performed and the individual circumstances of each case. Professionals are expected to comply with good standards of conduct and approved practices. It is a measure of diligence above that of an ordinary person or non-specialist. The boundaries of professional diligence are not always clear-cut; in certain cases assessing the diligence of a trader may require a close examination of all the relevant facts. For example, the manager of a restaurant has a duty to ensure that the ingredients used are fresh and meals properly prepared. A manager will clearly fail to comply with the professional diligence requirement if he does not ensure that food is properly handled, prepared, and served (eg that it is kept at the proper temperature or is in contact only with plates or utensils that are clean). However, if a customer becomes ill because he is allergic to a particular type of food that he has eaten in that restaurant, the manager will not be held responsible. Restaurant managers are not doctors and cannot be responsible for every accident that occurs to their customers.

(b) Material Distortion

According to Article 2(e), ‘to materially distort the economic behaviour of consumers’ means ‘using a commercial practice to appreciably impair the

37Directive 2005/29/EC, above n 2.

38Art 2(h) of ibid.

The UCPD and its General Prohibition 23

consumer’s ability to make an informed decision and thereby causing the consumer to take a transactional decision that he would not have taken otherwise’.39 The material distortion test aims to verify whether the practice has the potential to distort the consumer’s economic behaviour. This concept is at the core of the consumer protection legal systems in the Member States40 and abroad. The US Federal Statement on Deception also covers illegitimate commercial practices that are likely to deceive the consumer and thereby affect his economic behaviour.

The rationale of most of these systems is that unfair commercial practices distort consumer preferences by impairing their capacity or freedom of choice. Consumers buy unwanted products, accept terms and conditions that they would not have accepted, or turn to products that, absent the unfair practice, they would have regarded as inferior substitutes. This causes a market failure that marketing laws aim to redress.

The test, however, does not require proof that consumers have suffered economic damage (eg monetary harm). In some cases, unfair commercial practices will cause economic damage to the consumer as, for example, when sellers coerce the consumer to pay a disproportionately high price or to buy a defective product. However, the insertion of an economic damage requirement as a precondition to acting under the Directive would have been inappropriate as it would significantly have diminished the current level of consumer protection in the EU. Claimants would have to prove not only that the commercial practice caused the consumer to purchase something that he would otherwise not have purchased, but also that the consumer is worse off after the transaction. This is clearly unacceptable and impractical. In most cases, it would be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to prove and quantify the financial loss. This is particularly true where consumers have not yet bought the product because the practice

(eg a misleading advertising campaign) has not yet been launched or has only recently been launched.

The use of the adverb ‘appreciably’ in the definition introduces a threshold. Practices falling below this threshold will be considered de minimis and, thus, legitimate under the Directive. For example, the offer of refreshments at the commercial premises of the trader could have a

39Art 2(f) of ibid.

40This concept is also present in the Misleading Advertising Directive. Art 1(2) of the Misleading Advertising Directive defines misleading advertising as ‘any advertising which in any way, including its presentation, deceives or is likely to deceive the persons to whom it is addressed or whom it reaches and which, by reason of its deceptive nature, is likely to affect their economic behaviour and for these reasons injures or is likely to injure competitors’: see Council Directive 84/450/EEC of 10 Sept 1984 concerning misleading and comparative advertising, [1984] OJ L 250/17, as amended by Directive 97/55/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council [1997] OJ L 290/18.

24 Giuseppe B Abbamonte

moderate influence, but it is not likely to change consumer behaviour or cause him to make a transactional decision that he would not have otherwise made.

(c) The Average Consumer

The average consumer is the benchmark against which the unfairness of a commercial practice needs to be assessed. The average consumer test is a creation of the European Court of Justice. The Court confirmed the concept in a number of preliminary rulings on the interpretation of Articles 30 and 36 of the EC Treaty (now, after amendment, Articles 28 and 30 EC) and of provisions of secondary legislation (ie the Misleading Advertising Directive and the Community Trade Mark Regulation41). Most of the cases were about restrictions on the sale or marketing of a product on the basis of consumer protection from misleading advertising. According to the Court, ‘in order to determine whether a particular description, trade mark or promotional description or statement is misleading, it is necessary to take into account the presumed expectations of an average consumer who is reasonably well informed and reasonably observant and circumspect’.42

The test is based on the principle of proportionality. A national measure prohibiting claims (eg puffery) that might only deceive a few ‘simpleton’ and superficial consumers would be disproportionate to the objective pursued and create an unjustified barrier to trade. The test strikes the right balance between the need to protect consumers and the promotion of free trade in an openly competitive market. It is based on the standard of a hypothetical consumer and assumes that consumers should behave like rational economic operators. They should inform themselves about the quality and price of products and make efficient choices. The Court of First Instance has confirmed the test in many instances and, in assessing the likelihood of confusion of certain trade marks, has given some indications as to the behaviour of the average consumer. According to the Court of First Instance, ‘[t]he average consumer normally perceives a mark as a whole and does not proceed to analyse its various details . . . In addition, account

41See Art 28 and 30 of the Treaty establishing the European Community; Directive 84/450/ EEC, above n 41; Council Regulation (EC) No 40/94 of 20 Dec 1993 on the Community Trademark [1994] OJ L 11/1.

42The case law on the average consumer is vast. The test has been recently confirmed in the judgment of 9 Mar 2006 in Case C–421/04 Matrazen Concord, not yet reported. Some leading cases on the average consumers are Cases C–210/96 Gut Springenheide, Rudolf Tusky [1998] ECR I–04657; C–220/98 Estée Lauder v Lancaster (‘Lifting’) [2000] ECR I–00117; C–99/01 Linhart & Biffl v Unabhängiger Verwaltungssenat [2002] ECR I–09375, para 31.

The UCPD and its General Prohibition 25

should be taken of the fact that the average consumer only rarely has the chance to make a direct comparison between the different marks but has to place his trust in the imperfect image of them that he has retained in his mind. It should also be borne in mind that the average consumer’s level of attention is likely to vary according to the category of goods and services in question’.43

The Directive codifies the average consumer test, which was not applied by the courts of certain Member States.44 Transposition of the test into national law should significantly reduce the scope for divergent assessments of similar practices across the EU and enhance legal certainty.

The Directive represents a good example of constructive dialogue between the Court and the legislator. An original feature of the Directive is that it not only turns this jurisprudence into law, but refines this jurisprudence by modulating the average consumer test when the interests of specific groups of consumers are at stake. First, when the practice is addressed at a specific group of consumers, such as children or rocket scientists, it will be assessed from the perspective of the average member of the group. In the case of an advertisement of a toy during a TV programme for children, for example, one will have to take into account the expectations and the likely reaction of the average child of the group targeted and disregard those of an exceptionally immature or mature child belonging to the same group.

A second refinement of the test concerns those commercial practices that are likely materially to distort the economic behaviour of only a clearly identifiable group of consumers who, for various reasons, are particularly vulnerable to the practice or the underlying product in a way that the trader could reasonably be expected to foresee. In this case, the practice will be assessed from the perspective of the average member of that vulnerable group. This provision does not require traders to do more than is reasonable, both in considering whether the practice would have an unfair impact on any clearly identifiable group of vulnerable consumers, and in taking steps to mitigate any such impact. Some consumers because of their extreme naïvety or ignorance may be misled by, or otherwise act irrationally in response to, even the most honest commercial

43See eg Joined Cases T–183/02 and T–184/02 El Corte Inglés v Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (‘Mundicolor’) [2004] ECR II–00965, para 68. See also Case T–20/02 Interquell GmbH v Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (‘Happydog’) [2004] ECR II–1001, para 37.

44Eg the Belgian Cour de Cassation in Saint Bryce (2000) maintained that ‘the consumer who needs protection is the least attentive consumer who accepts without criticism the representations made to him and who is not in a position to see through the traps, exaggerations or the manipulative silences’ (translation from French into English by the author); the Italian court responsible for misleading advertising (TAR (Tribunale Administrative Regionale) Lazio) refused to apply the test, holding that ‘the verification and enforcement powers of the Autorità Garante (the Italian public enforcement body) would be deprived of any effectiveness for the practical impossibility to determine on a case by case basis the average IQ of the consumer reached by the advert’: see TAR Lazio, decisions of 27 July 1998 No 2281 and of 18 June 2003 and order of 15 January 2003, No 241 (translation from Italian into English by the author).

26 Giuseppe B Abbamonte

practice. There may be, for example, a few simple-minded consumers who may believe that ‘Spaghetti Bolognese’ are actually made in Bologna or ‘Yorkshire Pudding’ in York. Traders, however, will not be liable for every interpretation of or action taken in response to their commercial practices by consumers. The real aim of the provision is to capture cases of outright fraud, such as the offer of winning lottery numbers to credulous consumers, and other practices that reach the generality of consumers but are likely to affect only vulnerable consumers. An example of the latter is aggressive door-to-door selling methods that do not affect the average consumer but are likely to intimidate certain groups of consumers, such as the elderly, who may be vulnerable to pressureselling. The common characteristic of these practices is that it is not possible to prove that they are targeted at the vulnerable group, since they reach the generality of consumers and are not explicitly addressed to the vulnerable ones. In reality, the intent of these practices is to reach the vulnerable ones. A charlatan may sell winning lottery numbers on his website that is open to the general public but he knows that only the credulous consumers will be attracted to his site and lured into the scam.

At the same time, in order to avoid overzealous application of the provision and holding advertisers liable for ‘puffery’,45 the Directive clarifies that it does not affect the common and legitimate advertising practice of making exaggerated statements or statements that are not meant to be taken literally.46

According to the case law of the Court of Justice on the average consumer,47 in order to apply the average consumer test, several considerations, including but not limited to social, linguistic and cultural factors, must be borne in mind. This reflects the fact that, in certain cases, peculiar social, linguistic and cultural features in a Member State may justify a different interpretation of the message contained in the commercial practice. Returning to the example given above, it could be argued that, on the basis of the average consumer test, requiring the foreign trader to provide the additional piece of information, D, could be justified in the light of social, cultural or linguistic factors. In other words, because of these factors, the consumers of the country of destination, unlike those in the country of origin, would be misled by the omission of D. This argument, it is argued, should be dismissed. According to the Court of Justice, social, linguistic and cultural factors are not the only ones to be taken into account in applying the average consumer test.48 For example, the fact that a commercial

45Puffery consists of statements which are not capable of measurement or which consumers do not take seriously. It is about subjective or hyperbolic statements, such as ‘the ultimate driving machine’ or ‘Red Bull gives you wings’.

46Art 5(3) of the Directive, above n 2.

47Case C–220/98 Estée Lauder v Lancaster (‘Lifting’) [2000] ECR I–00117, para 29.

48For a list of factors to be considered when applying the average consumer test, see the Opinion of Fennely AG, in Case C–220/98 Estée Lauder v Lancaster (‘Lifting’) [2000] ECR I–00117, para 30.

The UCPD and its General Prohibition 27

practice has freely circulated without causing consumer protection concerns in the country of origin is another consideration.49 Given the internal market clause and the full harmonisation of the Directive, this factor should be given prominence over other factors. Therefore, the fact that a commercial practice has circulated legitimately in the country of origin should create a strong presumption about its legality in the country of destination.

(d) The Autonomy of the General Prohibition

The following is an example that illustrates how the general prohibition may operate in practice. It is an unjustified discrimination by a trader to discriminate on the basis of nationality or place of residence of the consumer in the EU. This could be the case of the manager of a hotel who, without any objective reasons, applies different conditions (eg price) according to the nationality or residence of the customers. The manager may apply higher prices to European consumers who are resident abroad or do not have the nationality of the country where the hotel is situated. This type of behaviour would be contrary to the tests of the general clause because:

—an unjustified refusal to sell or discrimination cannot be considered as compatible with the measure of diligence to be expected of a good businessman. A diligent businessman must deal openly and not engage in any unjustified discrimination that could offend prospective purchasers. This consideration must a fortiori be valid in the Internal Market and the European Union, which promotes the general principle of non-discrimination;50 and

—an unjustified refusal to sell or discriminatory treatment can materially distort the economic behaviour of the average consumer. Because of refusal or discriminatory treatment, the preferences of the consumer may be altered. He could, for example, decide not to buy that product or to turn to a competitor whose products he considered to be lower substitutes.

49Ibid.

50See Art 12 of the Treaty establishing the European Community. For an application of the principle of non-discrimination to agreements between individuals see Case C–281/98

Angonese v Cassa di Risparmio di Bolzano SpA [2000] ECR I–04139, para 30 ff. In this case the Court applied the principle of non-discrimination set out in Art 48 of the EC Treaty (now, after amendment, Art 39 EC), which regulates the freedom of movement of workers. The Court stated that ‘the principle of non-discrimination set out in Article 48 is drafted in general terms and is not specifically addressed to the Member States’ (para 30 of the judgment). It is submitted that the same considerations must be applicable, a fortiori, to Art 12 EC, which sets out a general prohibition of discrimination, which cannot be restricted to the actions of public authorities.

28 Giuseppe B Abbamonte

(e) The Articulation of the Wording of the General Prohibition with the Provisions on Misleading and Marketing Practices

As indicated above, the tests of the general prohibition are reproduced with adaptations in the provisions on misleading and aggressive practices.

The provisions on misleading and aggressive practices do not contain a separate reference to the concept of professional diligence. This is because misleading consumers or treating them aggressively is considered in itself contrary to the requirements of professional diligence. If a practice is misleading or aggressive it will not have to pass the professional diligence test in order to be declared unfair. According to the Directive, misleading and aggressive practices automatically violate the requirements of professional diligence. This means that in practice the professional diligence test will have to be applied only when the practice is assessed under the general prohibition.

The same considerations apply to the ‘distortion’ element of the material distortion test. Under the Directive misleading and aggressive practices are per se deemed to distort or be likely to distort the consumer’s ability to make an informed decision. In other words, these practices will always ‘appreciably impair’ the consumer’s ability to make an informed decision. The concept of distortion, which is based on the broad concept of appreciable impairment of the consumer’s ability to make informed decisions (see Article 2(e)), has been adapted to fit the provisions on misleading and aggressive practices. This is why, for example, Article 6, which regulates misleading actions, replaces the appreciable impairment concept with the narrower concept of deception (‘deceives or is likely to deceive’).

The ‘materiality’ condition of the material distortion test is contained in the requirement in Articles 6, 7 and 8 that the commercial practice ‘thereby causes or is likely to cause the average consumer to take a transactional decision that he would not have taken otherwise’.

The impact of misleading and aggressive commercial practice on consumers will be assessed in line with the requirements of the general prohibition on the average consumer and the vulnerable consumer. This means, for example, that where a particular group of consumers is directly targeted the impact of the misleading or agressive practice will be assessed, under Article 5.2(b), from the perspective of the average member of that group.

6. THE ROLE OF SELF-REGULATION AND THE NEED FOR A

REGULATORY BACKSTOP

Certain European countries have a long-established tradition of self-regu- lation. Codes of conduct, which are not defined in legislation, are used to set standards of good business behaviour in a particular sector. Codes

The UCPD and its General Prohibition 29

of conduct may be used by business to give sector-specific application to some general legislative requirements. For example, in the field covered by the Directive, codes could bring added value by implementing the principles of the Directive in relevant sectors. In this context, well-established codes of conduct could reflect good business practice and be used to identify the requirements of professional diligence in concrete cases. One of the advantages of self-regulation is its flexibility. Codes may be modified much more rapidly than regulation in order to respond to market developments and to tackle new unfair commercial practices swiftly. Moreover, the control exercised by code owners to eliminate unfair commercial practices may avoid recourse to administrative and/or judicial enforcement. This should be encouraged on grounds of expediency. Whereas in certain countries an action before a court may last several years, in the first instance, a self-regulatory body is normally able to reach a decision much more quickly.51

The main disadvantage of codes of conduct is that they apply only to the firms that have committed themselves to abide by them. Codes of conduct do not apply to non-members and rogue trades who do not belong to any legitimate self-regulatory association. This is the main reason a regulatory backstop is always needed. Article 10 of the Directive, by stating that the Directive does not exclude the control of unfair commercial practices by codes, implicitly recognises the role of codes of conduct.52 The Directive, however, encourages self-regulation, not as a substitute but as a means of supplementing regulation. Proceedings before self-regulatory bodies should occur in addition to the ordinary court or administrative proceedings. Under Article 10(2), recourse to the self-regulatory control bodies shall never be deemed the equivalent of forgoing a means of judicial or administrative recourse.53 The Directive will not interfere with the important role played by self-regulation in certain countries in applying and enforcing the laws on unfair commercial practices. In these countries, the Directive will represent the regulatory backstop that is available when self-regulation does not yield the desired outcomes.

An important provision in connection with codes of conduct is contained in Article 6, which regulates misleading actions. Article 6.2(b) defines as misleading the non-compliance by a trader with commitments

51Eg, in Italy an action before a court may last up to 4 or more years at first instance, while the Giuri, which is the tribunal established by the Italian Advertising Code (Codice dell’Autodisciplina Pubblicitaria) gives its decisions in an average of 30 days: see Study on the Feasibility of a General Legislative Framework on Fair Trading by the Institut für Europäisches Wirtschaftsund Verbraucherrecht eV (Nov 2000), part III, at 143, available at http://europa.eu.int/comm/consumers/cons_int/safe_shop/fair_bus_pract/ studies_en.htm.

52Art 10 of the Directive, above n 2.

53Art 10(2) of ibid.