новая папка / Operative Standards for Cancer Surgery Volume I 1st Edition

.pdf

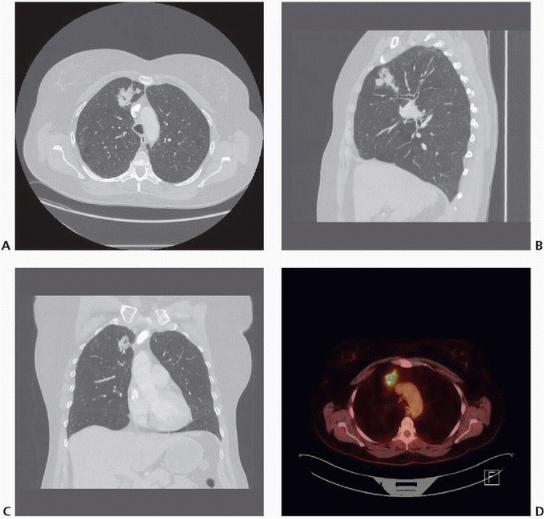

FIGURE 11-2 A: Axial, (B) sagittal, and (C) coronal CT images and (D) PET/CT image of a right upper lobe nonsmall cell lung cancer appropriate for anatomic right upper lobectomy. (Courtesy of Matthew Facktor, MD.)

If it is anatomically appropriate and likely to achieve negative surgical margins, lung-sparing anatomic resection (i.e., sleeve lobectomy) is preferable to pneumonectomy (Fig. 11-3A-D). Although pneumonectomy is a potentially safe curative-intent option in selected patients, the procedure is well known to impart a higher risk of shortand long-term morbidity and mortality.

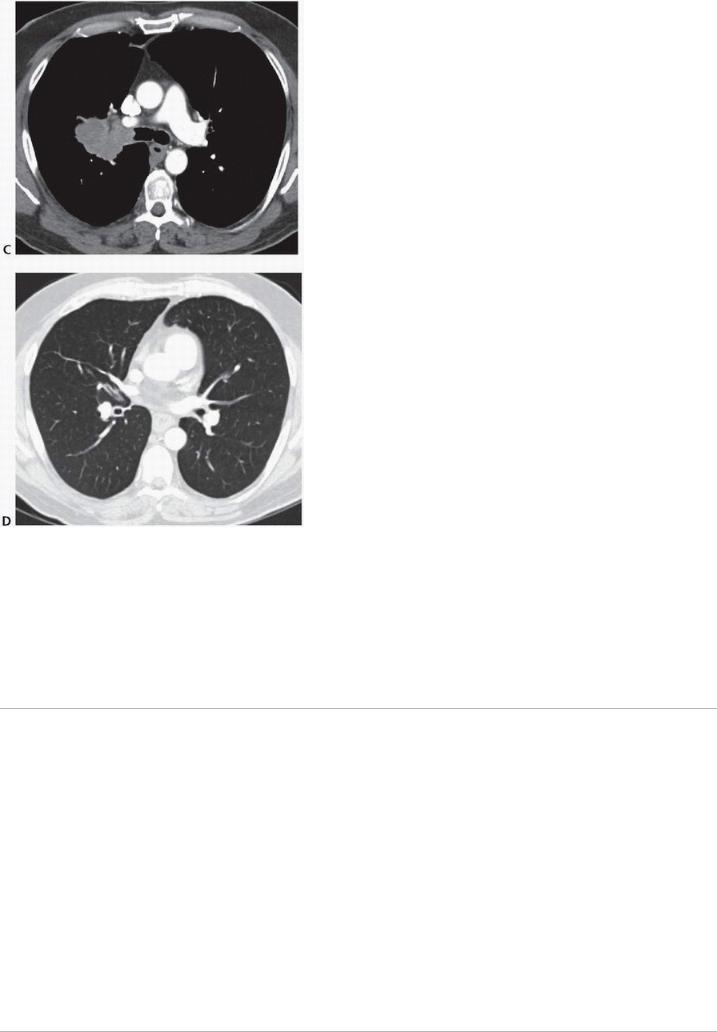

FIGURE 11-3 Right upper lobe malignancy extruding from right upper lobe orifice. A: Coronal CT lung window,

(B) coronal CT soft tissue view showing tumor protruding into bronchial lumen from right upper lobe orifice, (C) axial CT soft tissue view showing proximity to main carina, and (D) axial CT lung window showing patent airways distal to the tumor. Right upper lobe sleeve resection was accomplished with negative margins. (Courtesy of Bryan Meyers, MD, MPH.)

P.167

FIGURE 11-3 (Continued).

REFERENCES

1.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Non-small cell lung cancer practice guidelines (version 3. 2014). http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines_nojava.asp#site. Accessed March 25, 2015.

2.Ginsberg RJ, Rubinstein LV. Randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for T1 N0 non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Study Group. Ann Thorac Surg 1995;60(3):615-622.

3.Osarogiagbon RU, Ogbata O, Yu X. Number of lymph nodes associated with maximal reduction of longterm mortality risk in pathologic node-negative non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;97:385-

4.Haney JC, Hanna JM, Berry MF, et al. Differential prognostic significance of extralobar and intralobar nodal metastases in patients with surgically resected stage II non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;147(4):1164-1168.

5.Owen RM, Force SD, Gal AA, et al. Routine intraoperative frozen section analysis of bronchial margins is of limited utility in lung cancer resection. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;95(6):1859-1865.

Chapter 12

Pneumonectomy

CRITICAL ELEMENTS

Patient Selection

Patient Selection

Technical Aspects

Technical Aspects

Avoidance of Intraand Postoperative Complications

Avoidance of Intraand Postoperative Complications

1. PATIENT SELECTION

Recommendation: Proper preoperative evaluation with appropriate tests and imaging studies are essential to determine candidacy for pneumonectomy.

Type of Data: Retrospective.

Strength of Recommendation: Weak.

Rationale

Pneumonectomy is considered in patients who can physiologically tolerate the operation and whose disease cannot be cleared with lesser resections such as lobectomy, bilobectomy, or sleeve lobectomy. Patients for whom pneumonectomy is considered should first undergo careful evaluation to ensure that they can tolerate such an extensive lung resection. Preoperative pulmonary function tests, exercise testing, and room air arterial blood gas measurement, as well as imaging studies, can be used to assess a patient’s candidacy for

pneumonectomy.1,2,3,4 In general, pneumonectomy is indicated for the resection of lung cancer that cannot be removed by lobectomy or sleeve resection. Examples include central tumors involving the main bronchus (Fig. 12-1) and central tumors that involve the proximal vasculature or interlobar vasculature or cross the fissure(s). Although many consider hilar lymph node involvement to be an indication for pneumonectomy, there is no

survival advantage offered by pneumonectomy over sleeve lobectomy in this scenario.5

P.169

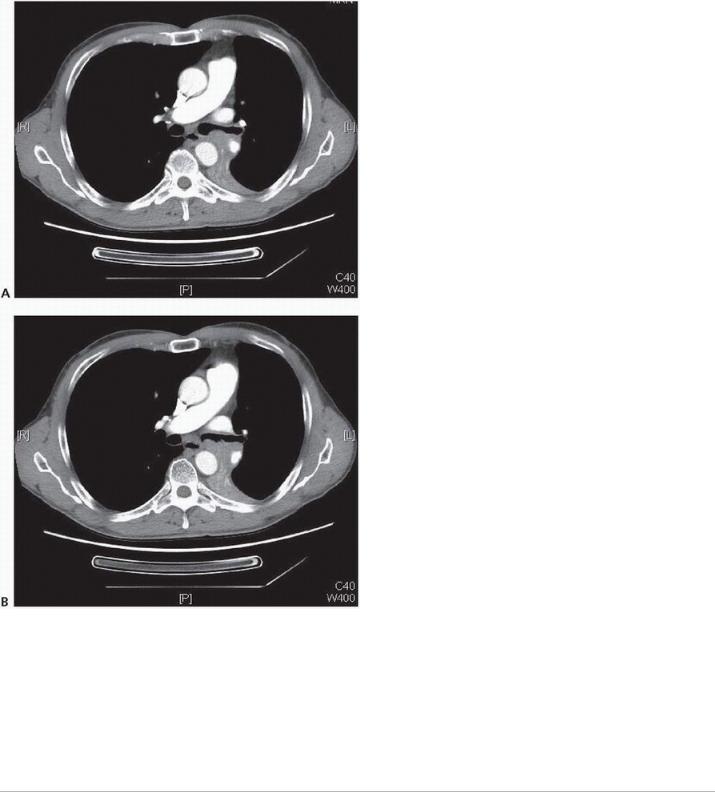

FIGURE 12-1 A,B: Axial CT images displaying proximal left main bronchus involvement by squamous cell cancer; left pneumonectomy was required for R0 resection. (Courtesy of Linda Martin, MD, MPH.)

The role of pneumonectomy in patients with N2 disease (Fig. 12-2) is controversial. Several authors presenting single-institution series have reported no overall increase in perioperative morbidity and mortality among patients

undergoing induction therapy followed by pneumonectomy.6,7,8 However, these same studies reported an

increased incidence of postoperative morbidity and mortality for patients undergoing right pneumonectomy.6,7

P.170

FIGURE 12-2 PET/CT image of malignant 4L lymph node, SUV of 4.9. “Confirmatory” endobronchial ultrasound biopsy of this node yielded squamous cell carcinoma. (Courtesy of Linda Martin, MD, MPH.)

One randomized multicenter study found no difference in survival between patients with stage III disease who underwent induction chemoradiotherapy followed by pneumonectomy and those who underwent induction

chemoradiotherapy followed by additional radiation therapy.9 However, these results were from an exploratory data analysis and not preplanned analyses. Another randomized trial of surgery versus radiotherapy in the setting of persistent N2 disease following induction chemotherapy failed to demonstrate any survival advantage

for pneumonectomy patients.10 However, these results were also the products of exploratory analyses. Given findings earlier, pneumonectomy can be safely performed from a technical standpoint but does not appear to offer an oncologic advantage in patients with stage IIIA disease in the setting of persistent N2 disease following induction chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy.

Preoperative Imaging

Preoperative imaging should be used to assist the surgeon with staging of the tumor. Positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) should be performed to rule out distant metastatic disease such

as liver, adrenal, and bone metastases.11 For patients with proximal tumors, CT with intravenous contrast should be used to evaluate for tumor extension into vascular structures, including the pulmonary veins and main pulmonary artery. Tumor invasion into the proximal pulmonary vein may mandate intrapericardial dissection of the vessel at the time of surgery. Tumor invasion into the left atrium via the pulmonary vein indicates T4 disease. In some cases, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to assess potential mediastinal or cardiac invasion if CT findings are equivocal. In addition, intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography can sometimes be helpful in assessing the degree of atrial involvement if visual inspection or palpation does not clearly demonstrate whether the tumor can be resected.

P.171

Bronchoscopic Evaluation of the Airway

Prior to or at the time of pneumonectomy, bronchoscopic evaluation of the airway is conducted. Although it should be performed before any kind of resection for lung cancer, this evaluation is especially important when pneumonectomy is being considered. The proximal location of the tumor in relation to both the mainstem bronchus and the carina should be noted to ensure that standard pneumonectomy is both necessary and feasible. In some patients with very proximal tumors, bronchoscopy may be optimally done on a date prior to the planned pneumonectomy to allow adequate time for pathologic analysis of bronchial and carinal biopsy samples to ensure that negative margins can be achieved with standard pneumonectomy. The surgeon should also take

particular note of any anatomic abnormalities, such as a tracheal bronchus. Although they are uncommon,12,13 such anomalies may alter the operative plan.

Evaluation of the Mediastinum

Prior to any exploration of the pleural space, the mediastinal lymph nodes should be thoroughly evaluated. In a center with reliable on-site frozen pathologic evaluation services, mediastinoscopy may be performed at the time of pneumonectomy and may be advantageous in terms of avoiding scar tissue or immobility of the mediastinum and hilum due to mediastinoscopy in a separate setting. The specifics of mediastinal nodal evaluation are discussed elsewhere in the manual.

Pneumonectomy versus Sleeve Lobectomy

Although no prospective randomized studies comparing pneumonectomy to sleeve resection have been performed, several studies have compared both the shortand longterm outcomes between the two techniques. Recent studies, including meta-analyses, have demonstrated that the two techniques are associated with similar rates of perioperative morbidity; importantly, however, sleeve lobectomy is associated with a lower rate of

perioperative mortality.14,15,16,17 From an oncologic perspective, the rates of locoregional recurrence in patients undergoing sleeve lobectomy are similar to those in patients undergoing pneumonectomy. However, patients undergoing sleeve lobectomy have higher rates of 5-year survival.

In addition, patients undergoing pneumonectomy appear to have worse postoperative and long-term quality of life outcomes than do patients undergoing sleeve resection. In the 12 months following surgical resection, pneumonectomy patients have significantly more dyspnea and pain than sleeve lobectomy or normal control

patients.18,19,20

Given these considerations, surgeons should carefully consider whether complete oncologic resection can be achieved with sleeve resection, rather than pneumonectomy, in a patient who can physiologically tolerate either procedure. Whenever possible, sleeve resection is preferable to pneumonectomy. For example, although pneumonectomy may be considered for a centrally located right upper lobe tumor (see Fig. 11-3 in Chapter 11), this tumor was successfully removed by sleeve lobectomy.

Intraoperative Decisions

Certain intraoperative findings should prompt the surgeon to perform a pneumonectomy rather than a lesser resection. Such findings include involvement of the proximal pulmonary

P.172 artery; the inability to separate the pulmonary veins, which would require more proximal resection; and disease extension into all parenchymal lobes. Surgeons should carefully consider the potential need for pneumonectomy before surgery in all patients with central tumors. Even if the need for pneumonectomy is believed to be unlikely, the surgeon should determine, before surgery, whether pneumonectomy would be physiologically feasible if more extensive or central disease is encountered at the time of resection.

2. TECHNICAL ASPECTS

Recommendation: Pneumonectomy can be performed via thoracotomy, thoracoscopically, or with robotic assistance, depending on the surgeon’s experience and preference. (Please also see Chapter 9.)

Type of Data: Retrospective.

Strength of Recommendation: Weak.

Rationale

The sequence in which the vessels and bronchus are divided depends on tumor anatomy. In some cases, dividing the bronchus first may allow for better visualization and easier mobilization of the vessels. However, the priority should be minimizing the length of the bronchial stump to prevent postoperative secretion pooling and reduce the potential for postoperative pneumonia or bronchopleural fistula. If the bronchus is divided first to facilitate safer manipulation and isolation of the vascular structures, particularly the pulmonary artery, then the bronchial stump should be reassessed after the lung has been removed to ensure that the stump is optimally short. The method used to divide the vessels and bronchus—by use of a stapling device or by sharp division and oversewing—is chosen by the surgeon.

Pulmonary Veins

The pulmonary veins are gently palpated to determine the extent of the tumor. If the veins are clear of tumor, each vein is gently and circumferentially dissected and then divided. Intrapericardial dissection is considered if the tumor appears to extend into the vein. Although some surgeons theorize that dividing the pulmonary veins prior to the pulmonary artery minimizes the chance of tumor embolization during manipulation, others believe that controlling and dividing the pulmonary artery first minimizes the amount of bleeding during subsequent dissection. In general, however, the order in which the vessels are divided is dictated by the tumor itself. The most appropriate approach involves taking the vessels in an order that facilitates safe and complete resection and likely varies from case to case based on specific tumor location.

Pulmonary Artery

If the tumor does not involve it, the main pulmonary artery is gently and circumferentially dissected. For tumors encroaching onto the pulmonary artery, however, several maneuvers may be used to provide additional length for the dissection and division

P.173 of the artery. On the right side, the superior vena cava can be mobilized medially to facilitate the dissection of the pulmonary artery. On the left side, the ligamentum arteriosum is divided to provide additional length for dissection; in this situation, care must be taken to avoid dividing the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Finally, intrapericardial dissection can also be performed to provide additional length for dissection and division. Pericardial defects, especially those on the right side, should be reapproximated or closed with a patch.

Bronchus

We recommend limiting the amount of dissection in the area of the proximal mainstem bronchus to preserve blood supply to the bronchial stump. However, complete clearing of the subcarinal mediastinal lymph nodes facilitates good visualization of the mainstem bronchus and thus an appropriate bronchial stump. Once the main bronchus has been circumferentially dissected, it is divided as close to the carina as possible to avoid leaving a long bronchial stump and its associated potential complications. If the bronchus is closed with suturing techniques, absorbable sutures are used to prevent the formation of suture granuloma. The resected bronchial margin is sent for frozen pathologic analysis to rule out microscopic disease. Despite the limited data in support of frozen sections of the bronchial margin, this may be the instance in which it is most helpful (refer to Chapter 9). Furthermore, we recommend testing the suture/staple line for air leaks using irrigation with saline or sterile water. The anesthesiologist is asked to perform a Valsalva maneuver to 30 cm H2O airway pressure, and any leaks

detected are closed with absorbable sutures. Finally, coverage of the bronchial stump with local soft tissue should be considered, especially on the right side. Although mediastinal tissue or mobilized pericardial fat can be useful in many cases, the use of an intercostal muscle flap or other autologous pedicled flap should be

considered for patients who have been treated with induction therapy.21

3. AVOIDANCE OF INTRA-AND POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS

Recommendation: Close adherence to the proper technical aspects of the operation and careful postoperative care decreases morbidity and mortality.

Type of Data: Retrospective.

Strength of Recommendation: Weak.

Rationale

During pneumonectomy, several steps can be taken to prevent or reduce postoperative complications.

Hemostasis

Meticulous attention to hemostasis is especially important during pneumonectomy. The use of blood products should be avoided if possible, as transfusion has been found to be an independent risk factor for postoperative

respiratory complications.22 Significant bleeding from any of the major vascular structures, bronchial vessels, or P.174

the chest wall can occur. Although life-threatening bleeding is rare, it should be considered a possibility in patients with hilar tumor involvement; patients who have extensive inflammation or infection or who have received prior radiation; and patients who have undergone prior lung resection. In such patients, it may be beneficial to gain proximal control of the major vascular structures prior to intrapericardial dissection and/or control of the hilar vessels.

Hemorrhage after pneumonectomy is relatively rare, with only 1.5% of patients requiring reoperation for

bleeding.23 In these patients, bleeding is primarily from either the chest wall or bronchial vessels and not the major pulmonary structures. Regardless, hemostasis of the chest wall and pleura and diligent inspection for any bleeding after lung removal is critical to prevent unnecessary blood loss and avoid the need for reoperation. In addition, placing a chest tube after pneumonectomy in patients in whom hilar or pleural resection was difficult can help to identify postoperative bleeding before it destabilizes the patient.

Cardiac Tamponade and Herniation

Because pneumonectomy can have life-threatening mechanical cardiac complications requiring emergent reoperation, echocardiography should be considered in patients who have refractory hypotension after pneumonectomy. Pericardial tamponade caused by a bleeding intrapericardial bronchial vessel or a retracted pulmonary structure is rare but has been described. In addition, a defect created in the pericardium during pneumonectomy can give rise to cardiac herniation; pericardial repair with patching is required to prevent this complication. Large pericardiotomy or pericardiectomy may be tolerated after left pneumonectomy but should

always be repaired after right pneumonectomy.24 In cases of severe patient instability, the thoracotomy may have to be reopened prior to obtaining any studies so that hemodynamic stability can be restored as soon as possible. It should also be stressed that, owing to the large pneumonectomy space, chest compressions after pneumonectomy are very unlikely to generate adequate blood flow through the heart; therefore, in the event of cardiac arrest, the patient’s chest should be reopened so that cardiac massage can be performed.

Pneumonia

Most patients have some degree of lung collapse after lung resection. Prevention of a subsequent pneumonia, which has a significant association with mortality, particularly in pneumonectomy patients, requires aggressive

treatment with pain control, pulmonary hygiene, and physical therapy.25,26 Frequent bronchoscopy and appropriate antibiotic therapy should be used in patients with poor respiration, excessive secretions, or