Definition of SECURITY

1

: the quality or state of being secure: as

a : freedom from danger : safety

b : freedom from fear or anxiety

c : freedom from the prospect of being laid off <job security>

2

a : something given, deposited, or pledged to make certain the fulfillment of an obligation

b : surety

3

: an instrument of investment in the form of a document (as a stock certificate or bond) providing evidence of its ownership

4

a : something that secures : protection

b (1) : measures taken to guard against espionage or sabotage, crime, attack, or escape (2) : an organization or department whose task is security

1. An investment instrument, other than an insurance policy or fixed annuity, issued by a corporation, government, or other organization which offers evidence of debt or equity. The official definition, from the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, is: "Any note, stock, treasury stock, bond, debenture, certificate of interest or participation in any profit-sharing agreement or in any oil, gas, or other mineral royaltyor lease, any collateral trust certificate, preorganization certificate or subscription, transferable share, investment contract, voting-trust certificate, certificate of deposit, for a security, any put, call, straddle, option, or privilege on any security, certificate of deposit, or group or index of securities (including any interest therein or based on the value thereof), or any put, call, straddle, option, or privilege entered into on a national securities exchange relating to foreign currency, or in general, any instrument commonly known as a 'security'; or any certificate of interest or participation in, temporary or interim certificate for, receipt for, or warrant or right to subscribe to or purchase, any of the foregoing; but shall not include currency or any note, draft, bill of exchange, or banker's acceptance which has a maturity at the time of issuance of not exceeding nine months, exclusive of days of grace, or any renewal thereof the maturity of which is likewise limited."

2. Property which is pledged as collateral for a loan.

Definition of 'Security'

A financial instrument that represents: an ownership position in a publicly-traded corporation (stock), a creditor relationship with governmental body or a corporation (bond), or rights to ownership as represented by an option. A security is a fungible, negotiable financial instrument that represents some type of financial value. The company or entity that issues the security is known as the issuer. For example, the issuer of a bond issue may be a municipal government raising funds for a particular project. Investors of securities may be retail investors - those who buy and sell securities on their own behalf and not for an organization - and wholesale investors - financial institutions acting on behalf of clients or acting on their own account. Institutional investors include investment banks, pension funds, managed funds and insurance companies.

Investopedia explains 'Security'

Securities are typically divided into debt securities and equities. A debt security is a type of security that represents money that is borrowed that must be repaid, with terms that define the amount borrowed, interest rate and maturity/renewal date. Debt securities include government and corporate bonds, certificates of deposit (CDs), preferred stock and collateralized securities (such as CDOs and CMOs). Equities represent ownership interest held by shareholders in a corporation, such as a stock. Unlike holders of debt securities who generally receive only interest and the repayment of the principal, holders of equity securities are able to profit from capital gains. In the United States, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and other self-regulatory organizations (such as the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority) regulate the public offer and sale of securities.

Definition of security

noun (plural securities)

1 [mass noun] the state of being free from danger or threat:the system is designed to provide maximum security against toxic spillsjob security

the safety of a state or organization against criminal activity such as terrorism, theft, or espionage:a matter of national security

procedures followed or measures taken to ensure the security of a state or organization:amid tight security the presidents met in the Colombian resort

the state of feeling safe, stable, and free from fear or anxiety:this man could give her the emotional security she needed

2a thing deposited or pledged as a guarantee of the fulfilment of an undertaking or the repayment of a loan, to be forfeited in case of default.

3 (often securities) a certificate attesting credit, the ownership of stocks or bonds, or the right to ownership connected with tradable derivatives.

n. pl. se·cu·ri·ties

1. Freedom from risk or danger; safety.

2. Freedom from doubt, anxiety, or fear; confidence.

3. Something that gives or assures safety, as:

a. A group or department of private guards: Call building security if a visitor acts suspicious.

b. Measures adopted by a government to prevent espionage, sabotage, or attack.

c. Measures adopted, as by a business or homeowner, to prevent a crime such as burglary or assault: Security was lax at the firm's smaller plant.

d. Measures adopted to prevent escape: Security in the prison is very tight.

4. Something deposited or given as assurance of the fulfillment of an obligation; a pledge.

5. One who undertakes to fulfill the obligation of another; a surety.

6. A document indicating ownership or creditorship; a stock certificate or bond.

International security

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Global security" redirects here. For the website of that name, see GlobalSecurity.org. For the academic journal, see International Security.

![]()

Terrorism like that on September 11 is one of the concerns of international security.[clarification needed]

International security consists of the measures taken by nations and international organizations, such as the United Nations, to ensure mutual survival and safety. These measures include military action and diplomatic agreements such as treaties and conventions. International and national security are invariably linked. International security is national security or state security in the global arena.

With the end of World War II, a new subject of study focusing on international security emerged. It began as an independent field of study, but was absorbed as a sub-field of international relations.[1] Since it took hold in the 1950s, the study of international security has been at the heart of international relations studies.[2] It covers labels like “security studies”, “strategic studies”, “peace studies”, and others.

There is no universal definition of the concept of security, but concepts in international security studies have been defined, such as sovereignty, war, anarchy, security dilemma, etc. The meaning of "security" is often treated as a common sense term that can be understood by "unacknowledged consensus".[3] As there is no universal concept, the content of international security has expanded over the years. Today it covers a variety of interconnected issues in the world that have an impact on survival. It ranges from the traditional or conventional modes of military power, the causes and consequences of war between states, economic strength, to ethnic, religious and ideological conflicts, trade and economic conflicts, energy supplies,science and technology, food, as well as threats to human security and the stability of states from environmental degradation, infectious diseases, climate change and the activities of non-state actors.[4]

While the wide perspective of international security regards everything as a security matter, the traditional approach focuses mainly or exclusively on military concerns.[1]

[edit]Concepts of security in the international arena

See also: National security#Definitions

There is no universal definition of the concept of security. Edward Kolodziej has compared it to a Tower of Babel.[5] Roland Paris (2004) views it as “in the eye of the beholder”.[6] But there is a consensus that it is important and multidimensional. It has been widely applied to “justify suspending civil liberties, making war, and massively reallocating resources during the last fifty years”.[7]

Walter Lippmann (1944) views security as the capability of a country to protect its core values, both in terms that a state need not sacrifice core values in avoiding war and can maintain them by winning war.[8] David Baldwin (1997) argues that pursuing security sometimes requires sacrificing other values, including marginal values and prime values.[7] Richard Ullman (1983) has suggested that a decrease in vulnerability is security.[9]

Arnold Wolfers (1952) argues that “security” is generally a normative term. It is applied by nations “in order to be either expedient - a rational means toward an accepted end - or moral, the best or least evil course of action”.[10] In the same way that people are different in sensing and identifying danger and threats, Wolfers argues that different nations also have different expectations of security. Not only is there a difference between forbearance of threats, but different nations also face different levels of threats because of their unique geographical, economic, ecological, and political environment.

Barry Buzan (2000) views the study of international security as more than a study of threats, but also a study of which threats that can be tolerated and which require immediate action.[11] He sees the concept of security as not either power or peace, but something in between.[12]

The concept of an international security actor has extended in all directions since the 1990s, from nations to groups, individuals, international systems, NGOs, and local governments.[13]

[edit]The Multi-Sum Security Principle

Traditional approaches to international security usually focus on state actors and their military capacities to protect national security. However, over the last decades the definition of security has been extended to cope with the 21st century globalized international community, its rapid technological developments and global threats that emerged out of this process. One such comprehensive definition has been proposed by Nayef Al-Rodhan. What he calls the "Multi-sum security principle" is based on the assumption that "in a globalized world, security can no longer be thought of as a zero-sum game involving states alone. Global security, instead, has five dimensions that include human, environmental, national, transnational, and transcultural security, and therefore, global security and the security of any state or culture cannot be achieved without good governance at all levels that guarantees security through justice for all individuals, states, and cultures."[14]

Each of these five dimensions refers to a different set of substrates. The first dimension refers to human security, a concept that makes the principle referent object of security the individual, not the state. The second dimension is environmental security and includes issues like climate change, global warming, and access to resources. The third substrate refers to national security, defined as being linked to the state’s monopoly over use of force in a given territory and as a substrate of security that emphasizes the military and policing components of security. The fourth component deals with transnational threats such as organized crime, terrorism, and human trafficking. Finally, the integrity of diverse cultures and civilisational forms tackles the issue of transcultural security. According to this multi-faceted security framework all five dimensions of security need to be addressed in order to provide just and sustainable global security. It therefore advocates cooperative interaction between states and peaceful existence between cultural groups and civilizations.[15]

[edit]Traditional security

[edit]Introduction

The traditional security paradigm refers to a realist construct of security in which the referent object of security is the state. The prevalence of this theorem reached a peak during the Cold War. For almost half a century, major world powers entrusted the security of their nation to a balance of power among states. In this sense international stability relied on the premise that if state security is maintained, then the security of citizens will necessarily follow.[16] Traditional security relied on the anarchistic balance of power, a military build-up between the United States and the Soviet Union (the two superpowers), and on the absolute sovereignty of the nation state.[17] States were deemed to be rational entities, national interests and policy driven by the desire for absolute power.[17] Security was seen as protection from invasion; executed during proxy conflicts using technical and military capabilities.

As Cold War tensions receded, it became clear that the security of citizens was threatened by hardships arising from internal state activities as well as external aggressors. Civil wars were increasingly common and compounded existing poverty, disease, hunger, violence and human rights abuses. Traditional security policies had effectively masked these underlying basic human needs in the face of state security. Through neglect of its constituents, nation states had failed in their primary objective.[18]

More recently, the traditional state-centric notion of security has been challenged by more holistic approaches to security.[19] Among the approaches which seeks to acknowledge and address these basic threats to human safety are paradigms that include cooperative, comprehensive and collective measures, aimed to ensure security for the individual and, as a result, for the state.

To enhance international security against potential threats caused by terrorism and organized crime, there have been an increase in international cooperation, resulting in transnational policing. The international police Interpol shares information across international borders and this cooperation has been greatly enhanced by the arrival of the Internet and the ability to instantly transfer documents, films and photographs worldwide.

[edit]Theoretical approaches

Main article: International relations theory

[edit]Realism

[edit]Classical realism

Main article: Classical realism in international relations theory

In the field of international relations, realism has long been a dominant theory, from ancient military theories and writings of Chinese and Greek thinkers, Sun Tzu and Thucydides being two of the more notable, to Hobbes, Machiavelli and Rousseau. It is the foundation of contemporary international security studies. The twentieth century classical realism is mainly derived from Edward Hallett Carr's book The Twenty Years' Crisis.[20] The realist views anarchy and the absence of a power to regulate the interactions between states as the distinctive characteristics of international politics. Because of anarchy, or a constant state of antagonism, the international system differs from the domestic system.[21] Realism has a variety of sub-schools whose lines of thought are based on three core assumptions: groupism, egoism, and power-centrism.[22]According to classical realists, bad things happen because the people who make foreign policy are sometimes bad.[23]

[edit]Neorealism

Main article: Neorealism (international relations)

Beginning in the 1960s, with increasing criticism of realism, Kenneth Waltz tried to revive the traditional realist theory by translating some core realist ideas into a deductive, top-down theoretical framework that eventually came to be called neorealism.[22] Theory of International Politics[24]brought together and clarified many earlier realist ideas about how the features of the overall system of states affects the way states interact:

"Neorealism answers questions: Why the modern states-system has persisted in the face of attempts by certain states at dominance; why war among great powers recurred over centuries; and why states often find cooperation hard. In addition, the book forwarded one more specific theory: that great-power war would tend to be more frequent in multipolarity (an international system shaped by the power of three or more major states) than bipolarity (an international system shaped by two major states, or superpowers)."[25]

The main theories of neorealism are balance of power theory, balance of threat theory, security odilemma theory, offense-defense theory, hegemonic stability theory and power transition theory.

[edit]Liberalism

Main article: Liberalism in international relations theory

Liberalism has a shorter history than realism but has been a prominent theory since World War I. It is a concept with a variety of meanings. Liberal thinking dates back to philosophers such as Thomas Paine and Immanuel Kant, who argued that republican constitutions produce peace. Kant's concept of Perpetual Peace is arguably seen as the starting point of contemporary liberal thought.[26]

[edit]Economic liberalism

Economic liberalism assumes that economic openness and interdependence between countries makes them more peaceful than countries who are isolated. Eric Gartzke has written that economic freedom is 50 times more effective than democracy in creating peace.[27] Globalization has been important to economic liberalism.

[edit]Liberal institutionalism

Main article: Liberal institutionalism

Liberal institutionalism views international institutions as the main factor to avoid conflicts between nations. Liberal institutionalists argue that; although the anarchic system presupposed by realists cannot be made to disappear by institutions; the international environment that is constructed can influence the behavior of states within the system.[28] Varieties of international governmental organizations (IGOs) and international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) are seen as contributors to world peace.

[edit]Comparison between realism and liberalism

-

Realist and liberal security systems[29]

Theoretical base

Realist (alliance)

Liberal (community of law)

Structure of the international system

Material; static; anarchic; self-help system

Social; dynamic; governance without government

Conceptions of security

Basic principles

Accumulation of power

Integration

Strategies

Military deterrence; control of allies

Democratization; conflict resolution; rule of Law

Institutional features

Functional scope

Military realm only

Multiple issue areas

Criterion for membership

Strategic relevance

Democratic system of rule

Internal power structure

Reflects distribution of power; most likely hegemonic

Symmetrical; high degree of interdependence

Decision-making

Will of dominant power prevails

Democratically legitimized

Relation of system to its environment

Dissociated; perception of threat

Serves as an attractive model; open for association

[edit]Constructivism

Main article: Constructivism (international relations)

Since its founding in the 1980s, constructivism has become an influential approach in international security studies. “It is less a theory of international relations or security, however, than a broader social theory which then informs how we might approach the study of security.”[30]Constructivists argue that security is a social construction. They emphasize the importance of social, cultural and historical factors, which leads to different actors construing similar events differently.

[edit]Prominent thinkers

Barry Buzan – Copenhagen School Alexander Wendt – Constructivism Edward Hallett Carr – Classical realism Hans J. Morgenthau – Classical realism Immanuel Kant – Kantian liberalism John Mearsheimer – Neorealism Kathryn Sikkink – Constructivism Kenneth Waltz – Neorealism Machiavelli – Classical realism Peter J. Katzenstein – Constructivism Robert Axelrod – Liberal institutionalism Robert Gilpin – Neorealism Robert Jervis – Neorealism Robert Keohane – Liberal institutionalism Thomas Hobbes – Classical realism Thucydides – Classical realism

[edit]Human security

Main article: Human security

Human security derives from the traditional concept of security from military threats to the safety of people and communities.[31] It is an extension of mere existence (survival) to well-being and dignity of human beings.[31] Human security is an emerging school of thought about the practice of international security. There is no single definition of human security, it varies from “ a narrow term of prevention of violence to a broad comprehensive view that proposes development, human rights and traditional security together.” Critics of the concept of human security claim that it covers almost everything and that it is too broad to be the focus of research. There have also been criticisms of its challenge to the role of states and their sovereignty.[31]

Human security offers a critique of and advocates an alternative to the traditional state-based conception of security. Essentially, it argues that the proper referent for security is the individual and that state practices should reflect this rather than primarily focusing on securing borders through unilateral military action. The justification for the human security approach is said to be that the traditional conception of security is no longer appropriate or effective in the highly interconnected and interdependent modern world in which global threats such as poverty, environmental degradation, and terrorism supersede the traditional security threats of interstate attack and warfare. Further, state-interest-based arguments for human security propose that the international system is too interconnected for the state to maintain an isolationist international policy. Therefore, it argues that a state can best maintain its security and the security of its citizens by ensuring the security of others. It is need to be noted that without the traditional security no human security can be assured.

-

Traditional vs Human Security[17]

Type of security

Referent

Responsibility

Threats

Traditional

The state

Integrity of the state

Interstate war, nuclear proliferation, revolution, civil conflict

Human

The individual

Integrity of the individual

Disease, poverty, natural disaster, violence, landmines, human rights abuses

[edit]UNDP human security proposal

The 1994 UNDP Human Development Report (HDR)[32] proposes that increasing human security entails:

Investing in human development, not in arms;

Engaging policy makers to address the emerging peace dividend;

Giving the United Nations a clear mandate to promote and sustain development;

Enlarging the concept of development cooperation so that it includes all flows, not just aid;

Agreeing that 20 percent of national budgets and 20 percent of foreign aid be used for human development; and

Establishing an Economic Security Council.

The report elaborates on seven components to human security. Tadjbakhsh and Chenoy list them as follows:

-

Components of human security as per the HDR 1994 report[33]

Type of security

Definition

Threats

Economic security

An assured basic income

Poverty, unemployment, indebtedness, lack of income

Food security

Physical and economic access to basic food

Hunger, famines and the lack of physical and economic access to basic food

Health security

Protection from diseases and unhealthy lifestyles

Inadequate health care, new and recurrent diseases including epidemics and pandemics, poor nutrition and unsafe environment, unsafe lifestyles

Environmental security

Healthy physical environment

Environmental degradation, natural disasters, pollution and resource depletion

Personal security

Security from physical violence

From the state (torture), other states (war), groups of people (ethnic tension), individuals or gangs (crime), industrial, workplace or traffic accidents

Community security

Safe membership in a group

From the group (oppressive practices), between groups (ethnic violence), from dominant groups (e.g. indigenous people vulnerability)

Political security

Living in a society that honors basic human rights

Political or state repression, including torture, disappearance, human rights violations, detention and imprisonment

Security

X-ray machines and metal detectors are used to control what is allowed to pass through an airport security perimeter.

Security spikes protect a gated community in the East End of London.

Security checkpoint at the entrance to theDelta Air Lines corporate headquarters inAtlanta

Security is the degree of protection to safeguard a nation, union of nations, persons or person against danger, damage, loss, and crime. Security as a form of protection are structures and processes that provide or improve security as a condition.The Institute for Security and Open Methodologies (ISECOM) in the OSSTMM 3 defines security as "a form of protection where a separation is created between the assets and the threat". This includes but is not limited to the elimination of either the asset or the threat. Security as a national condition was defined in a United Nations study (1986):[citation needed] so that countries can develop and progress safely.

Security has to be compared to related concepts: safety, continuity, reliability. The key difference between security and reliability is that security must take into account the actions of people attempting to cause destruction.

Different scenarios also give rise to the context in which security is maintained:

With respect to classified matter, the condition that prevents unauthorized persons from having access to official information that is safeguarded in the interests of national security.

Measures taken by a military unit, an activity or installation to protect itself against all acts designed to, or which may, impair its effectiveness.

[edit]Perceived security compared to real security

Perception of security may be poorly mapped to measureable objective security. For example, the fear of earthquakes has been reported to be more common than the fear of slipping on the bathroom floor although the latter kills many more people than the former.[1] Similarly, the perceived effectiveness of security measures is sometimes different from the actual security provided by those measures. The presence of security protections may even be taken for security itself. For example, twocomputer security programs could be interfering with each other and even cancelling each other's effect, while the owner believes s/he is getting double the protection.

Security theater is a critical term for deployment of measures primarily aimed at raising subjective security in a population without a genuine or commensurate concern for the effects of that measure on—and possibly decreasing—objective security. For example, some consider the screening of airline passengers based on static databases to have been Security Theater and Computer Assisted Passenger Prescreening System to have created a decrease in objective security.

Perception of security can also increase objective security when it affects or deters malicious behavior, as with visual signs of security protections, such as video surveillance, alarm systems in a home, or an anti-theft system in a car such as avehicle tracking system or warning sign.

Since some intruders will decide not to attempt to break into such areas or vehicles, there can actually be less damage to windows in addition to protection of valuable objects inside. Without such advertisement, a car-thief might, for example, approach a car, break the window, and then flee in response to an alarm being triggered. Either way, perhaps the car itself and the objects inside aren't stolen, but with perceived security even the windows of the car have a lower chance of being damaged, increasing the financial security of its owner(s).

However, the non-profit, security research group, ISECOM, has determined that such signs may actually increase the violence, daring, and desperation of an intruder.[2] This claim shows that perceived security works mostly on the provider and is not security at all.[3]

It is important, however, for signs advertising security not to give clues as to how to subvert that security, for example in the case where a home burglar might be more likely to break into a certain home if he or she is able to learn beforehand which company makes its security system.

[edit]Categorizing security

There is an immense literature on the analysis and categorization of security. Part of the reason for this is that, in most security systems, the "weakest link in the chain" is the most important. The situation is asymmetric since the 'defender' must cover all points of attack while the attacker need only identify a single weak point upon which to concentrate.

Politics

Collective security

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Collective security can be understood as a security arrangement, regional or global, in which each state in the system accepts that the security of one is the concern of all, and agrees to join in a collective response to threats to, and breaches of, the peace. Collective security is more ambitious than systems of alliance security or collective defence in that it seeks to encompass the totality of states within a region or indeed globally, and to address a wide range of possible threats. While collective security is an idea with a long history, its implementation in practice has proved problematic. Several prerequisites have to be met for it to have a chance of working.

Contents [hide]

|

[edit]History

[edit]Early mentions

Collective security, as suggested by many, is one of the most promising approaches for peace and a valuable device for power management on an international scale. Cardinal Richelieu proposed a scheme for collective security in 1629, which was partially reflected in the 1648 Peace of Westphalia. In the eighteenth century many proposals were made for collective security arrangements, especially in Europe.

The concept of a peaceful community of nations was outlined in 1795 in Immanuel Kant’s Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch.[1] Kant outlined the idea of a league of nations that would control conflict and promote peace between states.[2] However, he argues for the establishment of a peaceful world community not in a sense that there be a global government but in the hope that each state would declare itself as a free state that respects its citizens and welcomes foreign visitors as fellow rational beings. His key argument is that a union of free states would promote peaceful society worldwide: therefore, in his view, there can be a perpetual peace shaped by the international community rather than by a world government.[3]

Bahá'u'lláh (1817–1892), the founder of the Bahá'í Faith, prescribed collective security as a means to establish world peace in his writings during the 19th century:

The time must come when the imperative necessity for the holding of a vast, an all-embracing assemblage of men will be universally realized. The rulers and kings of the earth must needs attend it, and, participating in its deliberations, must consider such ways and means as will lay the foundations of the world's Great Peace amongst men. Such a peace demandeth that the Great Powers should resolve, for the sake of the tranquility of the peoples of the earth, to be fully reconciled among themselves. Should any king take up arms against another, all should unitedly arise and prevent him. If this be done, the nations of the world will no longer require any armaments, except for the purpose of preserving the security of their realms and of maintaining internal order within their territories. This will ensure the peace and composure of every people, government and nation.[4]

International co-operation to promote collective security originated in the Concert of Europe that developed after the Napoleonic Wars in the nineteenth century in an attempt to maintain the status quo between European states and so avoid war.[5][6] This period also saw the development of international law with the first Geneva Conventions establishing laws about humanitarian relief during war and the international Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 governing rules of war and the peaceful settlement of international disputes.[7][8]

The forerunner of the League of Nations, the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), was formed by peace activists William Randal Cremer and Frédéric Passy in 1889. The organization was international in scope with a third of the members of parliament, in the 24 countries with parliaments, serving as members of the IPU by 1914. Its aims were to encourage governments to solve international disputes by peaceful means and arbitration and annual conferences were held to help governments refine the process of international arbitration. The IPU's structure consisted of a Council headed by a President which would later be reflected in the structure of the League.[9]

At the start of the twentieth century two power blocs emerged through alliances between the European Great Powers. It was these alliances that came into effect at the start of the First World War in 1914, drawing all the major European powers into the war. This was the first major war in Europe between industrialized countries and the first time in Western Europe the results of industrialization (for example mass production) had been dedicated to war. The result of this industrial warfare was an unprecedented casualty level with eight and a half million members of armed services dead, an estimated 21 million wounded, and approximately 10 million civilian deaths.[10][11]

By the time the fighting ended in November 1918, the war had had a profound impact, affecting the social, political and economic systems of Europe and inflicting psychological and physical damage on the continent.[12] Anti-war sentiment rose across the world; the First World War was described as "the war to end all wars",[13][14] and its possible causes were vigorously investigated. The causes identified included arms races, alliances, secret diplomacy, and the freedom of sovereign states to enter into war for their own benefit. The perceived remedies to these were seen as the creation of an international organization whose aim was to prevent future war through disarmament, open diplomacy, international co-operation, restrictions on the right to wage wars, and penalties that made war unattractive to nations.[15]

[edit]Collective security in the League of Nations

After World War I, the first large scale attempt to provide collective security in modern times was the establishment of the League of Nations in 1919-20. The provisions of the League of Nations Covenant represented a weak system for decision-making and for collective action. An example of the failure of the League of Nations' collective security is the Manchurian Crisis, when Japan occupied part of China (which was a League member). After the invasion, members of the League passed a resolution calling for Japan to withdraw or face severe penalties. Given that every nation on the League of Nations council had veto power, Japan promptly vetoed the resolution, severely limiting the LN's ability to respond. After two years of deliberation, the League passed a resolution condemning the invasion without committing the League's members to any action against it. The Japanese replied by quitting the League.

A similar process occurred in 1935, when Italy invaded Ethiopia. Sanctions were passed, but Italy would have vetoed any stronger resolution. Additionally, Britain and France sought to court Italy's government as a potential deterrent to Hitler, given that Mussolini was not yet in what would become the Axis alliance of World War II. Thus, neither enforced any serious sanctions against the Italian government. Additionally, in this case and with the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, the absence of the USA from the League of Nations deprived the LN of another major power that could have used economic leverage against either of the aggressor states. Inaction by the League subjected it to criticisms that it was weak and concerned more with European issues (most leading members were European), and did not deter Hitler from his plans to dominate Europe. The Ethiopian monarch Emperor Haile Selassie I continued to support collective security though, having assessed that impotence lay not in the principle but in its covenantors commitment to honor its tenets.

One active and articulate exponent of collective security during the immediate pre-war years was the Soviet foreign minister Maxim Litvinov. However, there are grounds for doubt about the depth of Soviet commitment to this principle, as well as that of Western powers. After the Munich Agreement in September 1938 and the passivity of outside powers in the face of German occupation of the remainder of Czechoslovakia in March 1939 it was shown that the Western Powers were not prepared to engage in collective security against aggression by the Axis Powers together with the Soviet Union, Soviet foreign policy was revised and Litvinov was replaced as foreign minister in early May 1939, in order to facilitate the negotiations that led to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with Germany, signed by Litvinov's successor, Vyacheslav Molotov, on August 23 of that year. The war in Europe broke out a week later, with the German invasion of Poland on September 1.

[edit]Recent events

The 1945 United Nations Charter, although containing stronger provisions for decision-making and collective military action than those of the League of Nations Covenant, does not represent a complete system of collective security, but rather a balance between collective action on the one hand and continued operation of the states system (including the continued special roles of great powers) on the other.

Cited examples of the limitations of collective security include the Falklands War. When Argentina invaded the islands, which are overseas territories of the United Kingdom, many UN members stayed out of the issue, as it did not directly concern them. There was also a controversy about the United States role in that conflict due their obligations as an Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance (the "Rio Pact") member. However, many politicians who view the system as having faults also believe it remains a useful tool for keeping international peace.

The role of the UN and collective security in general is also evolving given the rise of internal state conflicts since the end of WWII, there have been 111 military conflicts world wide, but only 9 of which have involved two or more states going to war with one another. The remainder have either been internal civil wars or civil wars where other nations intervened in some manner. This means that collective security may have to evolve towards providing a means to ensure stability and a fair international resolution to those internal conflicts. Whether this will involve more powerful peacekeeping forces or a larger role for the UN diplomatically will likely be judged from a case to case basis.

[edit]Theory

Collective security can be understood as a security arrangement in which all states cooperate collectively to provide security for all by the actions of all against any states within the groups which might challenge the existing order by using force. This contrasts with self-help strategies of engaging in war for purely immediate national interest. While collective security is possible, several prerequisites have to be met for it to work.

Sovereign nations eager to maintain the status quo, willingly cooperate, accepting a degree of vulnerability and in some cases of minor nations, also accede to the interests of the chief contributing nations organising the collective security. Collective Security is achieved by setting up an international cooperative organisation, under the auspices of international law and this gives rise to a form of international collective governance, albeit limited in scope and effectiveness. The collective security organisation then becomes an arena for diplomacy, balance of power and exercise of soft power. The use of hard power by states, unless legitimised by the Collective Security organisation, is considered illegitimate, reprehensible and needing remediation of some kind. The collective security organisation not only gives cheaper security, but also may be the only practicable means of security for smaller nations against more powerful threatening neighbours without the need of joining the camp of the nations balancing their neighbours.

The concept of "collective security" forwarded by men such as Michael Joseph Savage, Martin Wight, Immanuel Kant, and Woodrow Wilson, are deemed to apply interests in security in a broad manner, to "avoid grouping powers into opposing camps, and refusing to draw dividing lines that would leave anyone out."[16] The term "collective security" has also been cited as a principle of the United Nations, and the League of Nations before that. By employing a system of collective security, the UN hopes to dissuade any member state from acting in a manner likely to threaten peace, thereby avoiding any conflict.

[edit]Basic assumptions

Organski (1960) lists five basic assumptions underlying the theory of collective security :[17]

In an armed conflict, member nation-states will be able to agree on which nation is the aggressor.

All member nation-states are equally committed to contain and constrain the aggression, irrespective of its source or origin.

All member nation-states have identical freedom of action and ability to join in proceedings against the aggressor.

The cumulative power of the cooperating members of the alliance for collective security will be adequate and sufficient to overpower the might of the aggressor.

In the light of the threat posed by the collective might of the nations of a collective security coalition, the aggressor nation will modify its policies, or if unwilling to do so, will be defeated.

[edit]Prerequisites

Morgenthau (1948) states that three prerequisites must be met for collective security to successfully prevent war :

The collective security system must be able to assemble military force in strength greatly in excess to that assembled by the aggressor(s) thereby deterring the aggressor(s) from attempting to change the world order defended by the collective security system.

Those nations, whose combined strength would be used for deterrence as mentioned in the first prerequisite, should have identical beliefs about the security of the world order that the collective is defending.

Nations must be willing to subordinate their conflicting interests to the common good defined in terms of the common defence of all member-states.

[edit]Collective defense

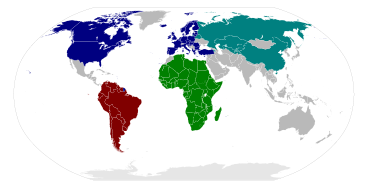

Current major military alliances

NATO, CSDP

SCO(Not a Military Block), CSTO

SADC

PSC

See also: List of military alliances

Collective defense (also collective defence) is an arrangement, usually formalized by a treaty and an organization, among participant states that commit support in defense of a member state if it is attacked by another state outside the organization. NATO is the best known collective defense organization. Its now famous Article V calls on (but does not fully commit) member states to assist another member under attack. This article was invoked after the September 11 attacks on the United States, after which other NATO members provided assistance to the US War on Terror in Afghanistan.

Collective defense has its roots in multiparty alliances, and entails benefits as well as risks. On the one hand, by combining and pooling resources, it can reduce any single state's cost of providing fully for its security. Smaller members of NATO, for example, have leeway to invest a greater proportion of their budget on non-military priorities, such as education or health, since they can count on other members to come to their defense, if needed.

On the other hand, collective defense also involves risky commitments. Member states can become embroiled in costly wars in which neither the direct victim nor the aggressor benefit. In the First World War, countries in the collective defense arrangement known as the Triple Entente (France, Britain, Russia) were pulled into war quickly when Russia started full mobilization against Austria-Hungary, whose ally Germany subsequently declared war on Russia.

|

Security and Security Complex: Operational Concepts

Security continues to be a top concern, a major issue of debate in national, regional, and global agendas. Likewise, it continues to require major resources and the sacrifice of many lives. However, as societies and international relations change, the approach to security also evolves. For that reason, security continues to be the focus of discussion, and to be redesigned in all its components and major dimensions, from its reference to international security systems. Starting from these debates, and in the light of the current international situation, what we propose in this paper are operational concepts of security and of security complex.