Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

may also occur.

Other late findings include cyanosis, clubbing, a ventricular gallop, and hemoptysis. Left-sided heart failure may also lead to signs of shock, such as hypotension, a thready pulse, and cold, clammy skin.

Mediastinal tumor. Orthopnea is an early sign of a mediastinal tumor, resulting from pressure of the tumor against the trachea, bronchus, or lung when the patient lies down. However, he may be asymptomatic until the tumor enlarges. Then it produces retrosternal chest pain, a dry cough, hoarseness, dysphagia, stertorous respirations, palpitations, and cyanosis. Examination reveals suprasternal retractions on inspiration, bulging of the chest wall, tracheal deviation, dilated jugular and superficial chest veins, and face, neck, and arm edema.

Special Considerations

To relieve orthopnea, place the patient in semi-Fowler’s or high Fowler’s position; if this doesn’t help, have him lean over a bedside table with his chest forward. If necessary, administer oxygen via nasal cannula. A diuretic may be needed to reduce lung fluid. Monitor electrolyte levels closely after administering diuretics. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors should be used for the patient with left-sided heart failure, unless contraindicated. Monitor his intake and output closely.

An electrocardiogram, chest X-ray, pulmonary function tests, and an arterial blood gas analysis may be necessary for further evaluation.

A central venous line or pulmonary artery catheter may be inserted to help measure central venous pressure and pulmonary artery wedge pressure and cardiac output, respectively.

Patient Counseling

Explain which signs and symptoms the patient should report and the dietary and fluid restrictions the patient needs. Discuss the importance of tracking the patient’s daily weight.

Pediatric Pointers

Common causes of orthopnea in a child include heart failure, croup, cystic fibrosis, and asthma. Sleeping in an infant seat may improve symptoms for a young child.

Geriatric Pointers

If the elderly patient is using more than one pillow at night, consider noncardiogenic pulmonary reasons for this, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease, sleep apnea, arthritis, or simply the need for greater comfort.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis. Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Orthostatic Hypotension[Postural hypotension]

In orthostatic hypotension, the patient’s blood pressure drops 15 to 20 mm Hg or more — with or without an increase in the heart rate of at least 20 beats/minute — when he rises from a supine to a sitting or standing position. (Blood pressure should be measured 5 minutes after the patient has changed his position.) This common sign indicates failure of compensatory vasomotor responses to adjust to position changes. It’s typically associated with light-headedness, syncope, or blurred vision and may occur in a hypotensive, normotensive, or hypertensive patient. Although commonly a nonpathologic sign in an elderly person, orthostatic hypotension may result from prolonged bed rest, fluid and electrolyte imbalance, endocrine or systemic disorders, and the effects of drugs.

To detect orthostatic hypotension, take and compare blood pressure readings with the patient supine, sitting, and then standing.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If you detect orthostatic hypotension, quickly check for tachycardia, an altered level of consciousness (LOC), and pale, clammy skin. If these signs are present, suspect hypovolemic shock. Insert a large-bore I.V. line for fluid or blood replacement. Take the patient’s vital signs every 15 minutes, and monitor his intake and output. Encourage bed rest.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient is in no danger, obtain a history. Ask the patient if he frequently experiences dizziness, weakness, or fainting when he stands. Also ask about associated symptoms, particularly fatigue, orthopnea, impotence, nausea, headaches, abdominal or chest discomfort, and GI bleeding. Then obtain a complete drug history.

Begin the physical examination by checking the patient’s skin turgor. Palpate peripheral pulses and auscultate the heart and lungs. Finally, test muscle strength and observe the patient’s gait for unsteadiness.

Medical Causes

Adrenal insufficiency. Adrenal insufficiency typically begins insidiously, with progressively severe signs and symptoms. Orthostatic hypotension may be accompanied by fatigue, muscle weakness, poor coordination, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, fasting hypoglycemia, weight loss, abdominal pain, irritability, and a weak, irregular pulse. Another common feature is hyperpigmentation — bronze coloring of the skin — which is especially prominent on the face, lips, gums, tongue, buccal mucosa, elbows, palms, knuckles, waist, and knees. Diarrhea, constipation, a decreased libido, amenorrhea, and syncope may also occur along with enhanced taste, smell, and hearing and cravings for salty food.

Alcoholism. Chronic alcoholism can lead to the development of peripheral neuropathy, which can present as orthostatic hypotension. Impotence is also a major issue in these patients. Other symptoms include numbness, tingling, nausea, vomiting, changes in bowel habits, and bizarre behavior.

Amyloidosis. Orthostatic hypotension is commonly associated with amyloid infiltration of the autonomic nerves. Associated signs and symptoms vary widely and include angina, tachycardia, dyspnea, orthopnea, fatigue, and a cough.

Hyperaldosteronism. Hyperaldosteronism typically produces orthostatic hypotension with sustained elevated blood pressure. Most other clinical effects of hyperaldosteronism result from hypokalemia, which increases neuromuscular irritability and produces muscle weakness, intermittent flaccid paralysis, fatigue, a headache, paresthesia and, possibly, tetany with positive Trousseau’s and Chvostek’s signs. The patient may also exhibit vision disturbances, nocturia, polydipsia, and personality changes. Diabetes mellitus is a common finding.

Hyponatremia. In hyponatremia, orthostatic hypotension is typically accompanied by a headache, profound thirst, tachycardia, nausea and vomiting, abdominal cramps, muscle twitching and weakness, fatigue, oliguria or anuria, cold clammy skin, poor skin turgor, irritability, seizures, and a decreased LOC. Cyanosis, a thready pulse and, eventually, vasomotor collapse may occur in a severe sodium deficit. Common causes include adrenal insufficiency, hypothyroidism, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, and the use of thiazide diuretics.

Hypovolemia. Mild to moderate hypovolemia may cause orthostatic hypotension associated with apathy, fatigue, muscle weakness, anorexia, nausea, and profound thirst. The patient may also develop dizziness, oliguria, sunken eyeballs, poor skin turgor, and dry mucous membranes.

Other Causes

Drugs. Certain drugs may cause orthostatic hypotension by reducing circulating blood volume, causing blood vessel dilation, or depressing the sympathetic nervous system. These drugs include antihypertensives (especially guanethidine monosulfate and the initial dosage of prazosin hydrochloride), tricyclic antidepressants, phenothiazines, levodopa, nitrates, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, morphine, bretylium tosylate, and spinal anesthesia. Large doses of diuretics can also cause orthostatic hypotension.

Treatments. Orthostatic hypotension is commonly associated with prolonged bed rest (24 hours or longer). It may also result from sympathectomy, which disrupts normal vasoconstrictive mechanisms.

Special Considerations

Monitor the patient’s fluid balance by carefully recording his intake and output and weighing him daily. To help minimize orthostatic hypotension, advise the patient to change his position gradually. Elevate the head of his bed and help him to a sitting position with his feet dangling over the side of the bed. If he can tolerate this position, have him sit in a chair for brief periods. Immediately return him to bed if he becomes dizzy or pale or displays other signs of hypotension.

Always keep the patient’s safety in mind. Never leave him unattended while he’s sitting or walking; evaluate his need for assistive devices, such as a cane or walker.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as hematocrit, serum electrolyte and drug levels, urinalysis, 12-lead electrocardiogram, and chest X-ray.

Patient Counseling

Explain the importance of avoiding volume depletion and how to change position gradually.

Pediatric Pointers

Because normal blood pressure is lower in children than in adults, familiarize yourself with normal age-specific values to detect orthostatic hypotension. From birth to age 3 months, normal systolic pressure is 40 to 80 mm Hg; from age 3 months to 1 year, 80 to 100 mm Hg; and from ages 1 to 12, 100 mm Hg plus 2 mm Hg for every year older than age 1. Diastolic blood pressure is first heard at about age 4; it’s normally 60 mm Hg at this age and gradually increases to 70 mm Hg by age 12.

The causes of orthostatic hypotension in children may be the same as those in adults.

Geriatric Pointers

Elderly patients commonly experience autonomic dysfunction, which can present as orthostatic hypotension. Postprandial hypotension occurs 45 to 60 minutes after a meal and has been documented in up to one-third of nursing home residents.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis. Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

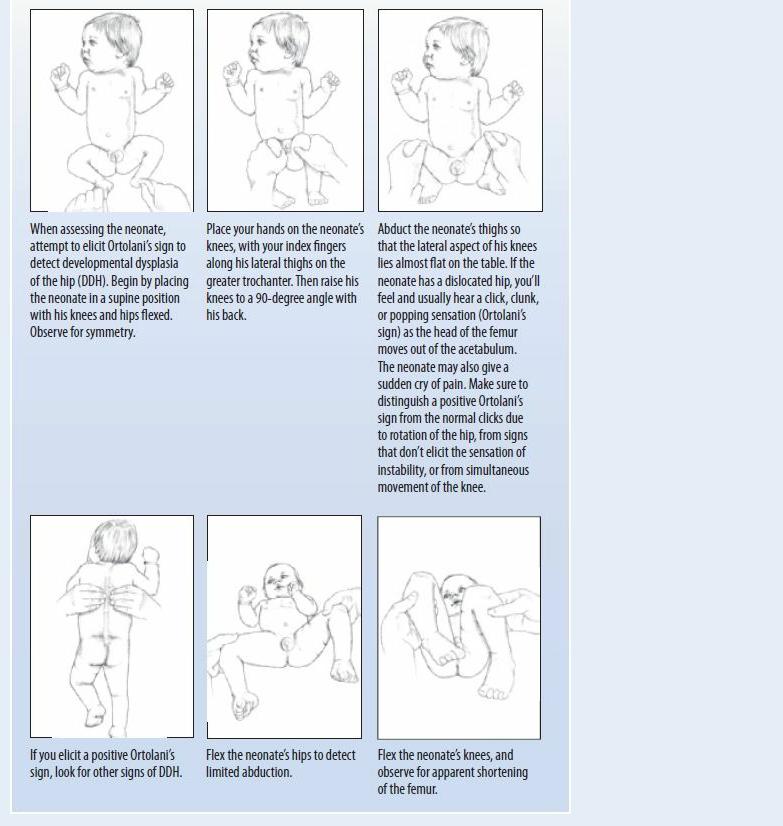

Ortolani’s Sign

Ortolani’s sign — a click, clunk, or popping sensation that’s felt and commonly heard when a neonate’s hip is flexed 90 degrees and abducted — is an indication of developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH); it results when the femoral head enters or exits the acetabulum. Screening for this sign is an important part of neonatal care because early detection and treatment of DDH improves the neonate’s chances of growing with a correctly formed, functional joint.

History and Physical Examination

During assessment for Ortolani’s sign, the neonate should be relaxed and lying supine. (See Detecting Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip, page 538.) After eliciting Ortolani’s sign, evaluate the neonate for asymmetrical gluteal folds, limited hip abduction, and unequal leg length.

Medical Causes

DDH. With complete dysplasia, the affected leg may appear shorter, or the affected hip may appear more prominent.

GENDER CUE

GENDER CUE

Most common in the female, DDH produces Ortolani’s sign, which may be accompanied by limited hip abduction and unequal gluteal folds. Usually, the neonate with DDH has no gross deformity or pain.

CULTURAL CUE

CULTURAL CUE

A strong relationship between hip dysplasia and methods of handling neonates has been demonstrated. For instance, Inuit and Navajo Indians have a high incidence of DDH, which may be related to their practice of wrapping neonates in blankets or strapping them to cradleboards. In cultures where mothers carry neonates on their backs or hips, such as in the Far East and Africa, hip dysplasia is rarely seen.

Special Considerations

Ortolani’s sign can be elicited only during the first 4 to 6 weeks of life; this is also the optimum time for effective corrective treatment. If treatment is delayed, DDH may cause degenerative hip changes, lordosis, joint malformation, and soft tissue damage. Various methods of abduction can be used to produce a stable joint. These methods include using soft splinting devices and a plaster hip spica cast.

Patient Counseling

Explain the neonate’s condition and its treatments to the parents. Teach them how to keep the affected limb in an abducted position.

EXAMINATION TIP Detecting Developmental Dysplasia of the

Hip

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Otorrhea

Otorrhea — drainage from the ear — may be bloody (otorrhagia), purulent, clear, or

serosanguineous. Its onset, duration, and severity provide clues to the underlying cause. This sign may result from disorders that affect the external ear canal or the middle ear, including allergy, infection, neoplasms, trauma, and collagen diseases. Otorrhea may occur alone or with other symptoms such as ear pain.

History and Physical Examination

Begin your evaluation by asking the patient when otorrhea began, noting how he recognized it. Did he clean the drainage from deep within the ear canal, or did he wipe it from the auricle? Have him describe the color, consistency, and odor of the drainage. Is it clear, purulent, or bloody? Does it occur in one or both ears? Is it continuous or intermittent? If the patient wears cotton in his ear to absorb the drainage, ask how often he changes it.

Then explore associated otologic symptoms, especially pain. Is there tenderness on movement of the pinna or tragus? Ask about vertigo, which is absent in disorders of the external ear canal. Also ask about tinnitus.

Next, check the patient’s medical history for recent upper respiratory infection or head trauma. Also, ask how he cleans his ears and if he’s an avid swimmer. Note a history of cancer, dermatitis, or immunosuppressant therapy.

Focus the physical examination on the patient’s external ear, middle ear, and tympanic membrane. (If his symptoms are unilateral, examine the uninvolved ear first as not to cross-contaminate.) Inspect the external ear, and apply pressure on the tragus and mastoid area to elicit tenderness. Then insert an otoscope, using the largest speculum that will comfortably fit into the ear canal. If necessary, clean cerumen, pus, or other debris from the canal. Observe for edema, erythema, crusts, or polyps. Inspect the tympanic membrane, which should look like a shiny, pearl-gray cone. Note color changes, perforation, absence of the normal light reflex (a cone of light appearing toward the bottom of the drum), or a bulging membrane.

Next, test hearing acuity. Have the patient occlude one ear while you whisper some common twosyllable words toward the unoccluded ear. Stand behind him so he doesn’t read your lips, and ask him to repeat what he heard. Perform the test on the other ear using different words. Then use a tuning fork to perform Weber’s and the Rinne tests. (See Differentiating Conductive from Sensorineural Hearing Loss, page 372.)

Complete your assessment by palpating the patient’s neck and his preauricular, parotid, and postauricular (mastoid) areas for lymphadenopathy. Also, test the function of cranial nerves VII, IX, X, and XI.

Medical Causes

Aural polyps. Aural polyps may produce foul, purulent and, perhaps, blood-streaked discharge. If they occlude the external ear canal, the polyps may cause partial hearing loss.

Basilar skull fracture. With a basilar skull fracture, otorrhea may be clear and watery and positive for glucose, representing cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage, or bloody, representing hemorrhage. Occasionally, inspection reveals blood behind the eardrum. Otorrhea may be accompanied by hearing loss, CSF or bloody rhinorrhea, periorbital ecchymosis (raccoon eyes), and mastoid ecchymosis (Battle’s sign). Cranial nerve palsies, a decreased level of consciousness, and a headache are other common findings.

Epidural abscess. In epidural abscess, profuse, creamy otorrhea is accompanied by steady,

throbbing ear pain; a fever; and a temporal or temporoparietal headache on the ipsilateral side. Myringitis (infectious). With acute infectious myringitis, small, reddened, blood-filled blebs erupt in the external ear canal, the tympanic membrane and, occasionally, the middle ear. Spontaneous rupture of these blebs causes serosanguineous otorrhea. Other features include severe ear pain, tenderness over the mastoid process and, rarely, a fever and hearing loss. Chronic infectious myringitis causes purulent otorrhea, pruritus, and gradual hearing loss.

Otitis externa. Acute otitis externa, commonly known as swimmer’s ear, usually causes purulent, yellow, sticky, foul-smelling otorrhea. Inspection may reveal white-green debris in the external ear canal. Associated findings include edema, erythema, pain, and itching of the auricle and external ear canal; severe tenderness with movement of the mastoid, tragus, mouth, or jaw; tenderness and swelling of surrounding nodes; and partial conductive hearing loss. The patient may also develop a low-grade fever and a headache ipsilateral to the affected ear.

Chronic otitis externa usually causes scanty, intermittent otorrhea that may be serous or purulent and possibly foul smelling. Its primary symptom, however, is itching. Related findings include edema and slight erythema.

Life-threatening malignant otitis externa produces debris in the ear canal, which may build up against the tympanic membrane, causing severe pain that’s especially acute during manipulation of the tragus or auricle. Most common in patients with diabetes and immunosuppressed patients, this fulminant bacterial infection may also cause pruritus, tinnitus and, possibly, unilateral hearing loss.

Otitis media. With acute otitis media, rupture of the tympanic membrane produces bloody, purulent otorrhea and relieves continuous or intermittent ear pain. Typically, a conductive hearing loss worsens over several hours.

With acute suppurative otitis media, the patient may also exhibit signs and symptoms of an upper respiratory infection — a sore throat, a cough, nasal discharge, and a headache. Other features include dizziness, a fever, nausea, and vomiting.

Chronic otitis media causes intermittent, purulent, foul-smelling otorrhea commonly associated with tympanic membrane perforation. Conductive hearing loss occurs gradually and may be accompanied by pain, nausea, and vertigo.

Trauma. Bloody otorrhea may result from trauma, such as a blow to the external ear, a foreign body in the ear, or barotrauma. Usually, bleeding is minimal or moderate; it may be accompanied by partial hearing loss.

Tumor (malignant). Squamous cell carcinoma of the external ear causes purulent otorrhea with itching; deep, boring ear pain; hearing loss; and, in late stages, facial paralysis.

In squamous cell carcinoma of the middle ear, blood-tinged otorrhea occurs early, typically accompanied by hearing loss on the affected side. Pain and facial paralysis are late features.

Special Considerations

Apply warm, moist compresses, heating pads, or hot water bottles to the patient’s ears to relieve inflammation and pain. Use cotton wicks to gently clean the draining ear or to apply topical drugs. Keep eardrops at room temperature; instillation of cold eardrops may cause vertigo. If the patient has impaired hearing, ensure that he understands everything that’s explained to him, using written messages if necessary.

Patient Counseling

Instruct the patient on safe ways to blow his nose and clean his ears. Stress the use of earplugs when swimming. Explain which signs and symptoms the patient should report.

Pediatric Pointers

When you examine or clean a child’s ear, remember that the auditory canal lies horizontally and that the pinna must be pulled downward and backward. Restrain a child during an ear procedure by having him sit on a parent’s lap with the ear to be examined facing you. Have him put one arm around the parent’s waist and the other down at his own side, and then ask the parent to hold the child in place. Or, if you are alone with the child, ask him to lie on his abdomen with his arms at his sides and his head turned so the affected ear faces the ceiling. Bend over him, restraining his upper body with your elbows and upper arms.

Perforation of the tympanic membrane secondary to otitis media is the most common cause of otorrhea in infants and young children. Children are also likely to insert foreign bodies into their ears, resulting in infection, pain, and purulent discharge.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012) Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012) Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

PQ

Pallor

Pallor is abnormal paleness or loss of skin color, which may develop suddenly or gradually. Although generalized pallor affects the entire body, it’s most apparent on the face, conjunctiva, oral mucosa, and nail beds. Localized pallor commonly affects a single limb.

How easily pallor is detected varies with skin color and the thickness and vascularity of underlying subcutaneous tissue. At times, it’s merely a subtle lightening of skin color that may be difficult to detect in dark-skinned persons; sometimes it’s evident only on the conjunctiva and oral mucosa.

Pallor may result from decreased peripheral oxyhemoglobin or decreased total oxyhemoglobin. The former reflects diminished peripheral blood flow associated with peripheral vasoconstriction or arterial occlusion or with low cardiac output. (Transient peripheral vasoconstriction may occur with exposure to cold, causing nonpathologic pallor.) The latter usually results from anemia, the chief cause of pallor. (See How Pallor Develops, page 544.)

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If generalized pallor suddenly develops, quickly look for signs of shock, such as tachycardia, hypotension, oliguria, and a decreased level of consciousness (LOC). Prepare to rapidly infuse fluids or blood. Obtain a blood sample for hemoglobin and serum glucose levels and hematocrit. Keep emergency resuscitation equipment nearby.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient’s condition permits, take a complete history. Does the patient or anyone in his family have a history of anemia or of a chronic disorder that might lead to pallor, such as renal failure, heart failure, or diabetes? Ask about the patient’s diet, particularly his intake of red meat and green vegetables.

Then, explore the pallor more fully. Find out when the patient first noticed it. Is it constant or intermittent? Does it occur when he’s exposed to the cold? Does it occur when he’s under emotional stress? Explore associated signs and symptoms, such as dizziness, fainting, orthostasis, weakness and fatigue on exertion, dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, menstrual irregularities, or loss of libido. If pallor is confined to one or both legs, ask the patient if walking is painful. Do his legs feel cold or numb? If pallor is confined to his fingers, ask about tingling and numbness.

Start the physical examination by taking the patient’s vital signs. Make sure to check for orthostatic hypotension. Auscultate the heart for gallops and murmurs and the lungs for crackles. Check the patient’s skin temperature — cold extremities commonly occur with vasoconstriction or arterial occlusion. Also, note skin ulceration. Examine the abdomen for splenomegaly. Finally, palpate peripheral pulses. An absent pulse in a pale extremity may indicate arterial occlusion,