Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

Medical Causes

Calculi. Renal and ureteral calculi produce intense unilateral, colicky flank pain. Typically, initial CVA pain radiates to the flank, suprapubic region, and perhaps the genitalia; abdominal and lower back pain is also possible. Nausea and vomiting commonly accompany severe pain. Associated findings include CVA tenderness, hematuria, hypoactive bowel sounds and, possibly, signs and symptoms of a UTI (urinary frequency and urgency, dysuria, nocturia, fatigue, a low-grade fever, and tenesmus).

Cortical necrosis (acute). Unilateral flank pain is usually severe. Accompanying findings include gross hematuria, anuria, leukocytosis, and a fever.

Obstructive uropathy. With acute obstruction, flank pain may be excruciating; with gradual obstruction, it’s typically a dull ache. With both, the pain may also localize in the upper abdomen and radiate to the groin. Nausea and vomiting, abdominal distention, anuria alternating with periods of oliguria and polyuria, and hypoactive bowel sounds may also occur. Additional findings — a palpable abdominal mass, CVA tenderness, and bladder distention — vary with the site and cause of the obstruction.

Papillary necrosis (acute). Intense bilateral flank pain occurs along with renal colic, CVA tenderness, and abdominal pain and rigidity. Urinary signs and symptoms include oliguria or anuria, hematuria, and pyuria, with associated high fever, chills, vomiting, and hypoactive bowel sounds.

Perirenal abscess. Intense unilateral flank pain and CVA tenderness accompany dysuria, a persistent high fever, chills and, in some patients, a palpable abdominal mass.

Polycystic kidney disease. Dull, aching, bilateral flank pain is commonly the earliest symptom of polycystic kidney disease. The pain can become severe and colicky if cysts rupture and clots migrate or cause obstruction. Nonspecific early findings include polyuria, increased blood pressure, and signs of a UTI. Later findings include hematuria and perineal, low back, and suprapubic pain.

Pyelonephritis (acute). Intense, constant, and unilateral or bilateral flank pain develops over a few hours or days along with typical urinary features: dysuria, nocturia, hematuria, urgency, frequency, and tenesmus. Other common findings include a persistent high fever, chills, anorexia, weakness, fatigue, generalized myalgia, abdominal pain, and marked CVA tenderness.

Renal cancer. Unilateral flank pain, gross hematuria, and a palpable flank mass form the classic clinical triad. Flank pain is usually dull and vague, although severe colicky pain can occur during bleeding or passage of clots. Associated signs and symptoms include a fever, increased blood pressure, and urine retention. Weight loss, leg edema, nausea, and vomiting are indications of advanced disease.

Renal infarction. Unilateral, constant, severe flank pain and tenderness typically accompany persistent, severe upper abdominal pain. The patient may also develop CVA tenderness, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, a fever, hypoactive bowel sounds, hematuria, and oliguria or anuria.

Renal trauma. Variable bilateral or unilateral flank pain is a common symptom. A visible or palpable flank mass may also exist, along with CVA or abdominal pain — which may be severe and radiate to the groin. Other findings include hematuria, oliguria, abdominal distention,

Turner’s sign, hypoactive bowel sounds, and nausea or vomiting. Severe injury may produce signs of shock, such as tachycardia and cool, clammy skin.

Renal vein thrombosis. Severe unilateral flank and lower back pain with CVA and epigastric tenderness typify the rapid onset of venous obstruction. Other features include a fever, hematuria, and leg edema. Bilateral flank pain, oliguria, and other uremic signs and symptoms (nausea, vomiting, and uremic fetor) typify bilateral obstruction.

Special Considerations

Administer pain medication. Continue to monitor the patient’s vital signs, and maintain a precise record of his intake and output.

Diagnostic evaluation may involve serial urine and serum analysis, excretory urography, flank ultrasonography, a computed tomography scan, voiding cystourethrography, cystoscopy, and retrograde ureteropyelography, urethrography, and cystography.

Patient Counseling

Explain the signs and symptoms to report and the importance of increased fluid intake (unless contraindicated). Emphasize the need to take drugs as prescribed and to keep follow-up appointments.

Pediatric Pointers

Assessment of flank pain can be difficult if a child can’t describe the pain. In such cases, transillumination of the abdomen and flanks may help in the assessment of bladder distention and identification of masses. Common causes of flank pain in a child include obstructive uropathy, acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, infantile polycystic kidney disease, and nephroblastoma.

REFERENCES

Bande, D., Abbara, S., & Kalva, S. P. (2011). Acute renal infarction secondary to calcific embolus from mitral annular calcification.

Cardiovascular Interventional Radiology, 34, 647–649.

Lopez, V. M. , & Glauser, J. (2010) . A case of renal artery thrombosis with renal infarction. Journal of Emergency Trauma and Shock, 3, 302.

Fontanel, Bulging

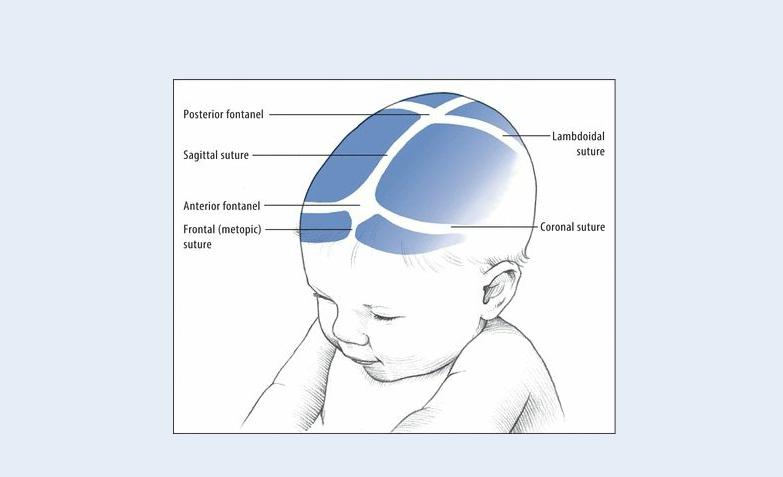

In a normal infant, the anterior fontanel, or “soft spot,” is flat, soft yet firm, and well demarcated against surrounding skull bones. The posterior fontanel shouldn’t be fused at birth but may be overriding following the birthing process. This fontanel usually closes by age 3 months. (See Locating Fontanels.) Subtle pulsations may be visible, reflecting the arterial pulse.

EXAMINATION TIP Locating Fontanels

EXAMINATION TIP Locating Fontanels

The anterior fontanel lies at the junction of the sagittal, coronal, and frontal sutures. It normally measures about 2.5 × 4 to 5 cm at birth and usually closes by age 18 to 20 months.

The posterior fontanel lies at the junction of the sagittal and lambdoidal sutures. It measures 1 to 2 cm around and normally closes by age 3 months.

A bulging fontanel — widened, tense, and with marked pulsations — is a cardinal sign of meningitis associated with increased intracranial pressure (ICP), a medical emergency. It can also be an indication of encephalitis or fluid overload such as in hydrocephalus. Because prolonged coughing, crying, or lying down can cause transient, physiologic bulging, the infant’s head should be observed and palpated while the infant is upright and relaxed to detect pathologic bulging.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If you detect a bulging fontanel, measure its size and the head circumference, and note the overall shape of the head. Take the infant’s vital signs, and determine his level of consciousness (LOC) by observing spontaneous activity, postural reflex activity, and sensory responses. Note whether the infant assumes a normal, flexed posture or one of extreme extension, opisthotonos, or hypotonia. Observe arm and leg movements; excessive tremulousness or frequent twitching may herald the onset of a seizure. Look for other signs of increased ICP: abnormal respiratory patterns and a distinctive, high-pitched cry.

Ensure airway patency, and have size-appropriate emergency equipment on hand. Provide oxygen, establish I.V. access, and if the infant is having a seizure, stay with him to prevent injury and administer an anticonvulsant. Administer an antibiotic, antipyretic, and osmotic diuretic to help reduce cerebral edema and decrease ICP. If these measures fail to reduce ICP, neuromuscular blockade, intubation, mechanical ventilation and, in rare cases, barbiturate coma and total body hypothermia may be necessary.

History and Physical Examination

When the infant’s condition is stabilized, you can begin investigating the underlying cause of increased ICP. Obtain the child’s medical history from a parent or caretaker, paying particular attention to a recent infection or trauma, including birth trauma. Has the infant or a family member had a recent rash or fever? Ask about changes in the infant’s behavior, such as frequent vomiting, lethargy, or disinterest in feeding.

Medical Causes

Increased ICP. Besides a bulging fontanel and increased head circumference, other early signs and symptoms are usually subtle and difficult to discern. They may include behavioral changes, irritability, fatigue, and vomiting. As ICP rises, the infant’s pupils may dilate and his LOC may decrease to drowsiness and eventual coma. Seizures commonly occur. Infections with meningitis and encephalitis can cause an increase in ICP and a bulging fontanel. Hydrocephalus, brain tumor, intracranial hemorrhage, and congestive heart failure are other possible causes.

Special Considerations

Closely monitor the infant’s condition, including urine output (via an indwelling urinary catheter, if necessary), and continue to observe him for seizures. Restrict fluids, and place the infant in the supine position, with his body tilted 30 degrees and his head up, to enhance cerebral venous drainage and reduce intracranial blood volume.

Clarify any diagnostic tests and assessments for the infant’s parents or caretaker. Such tests may include an intracranial computed tomography scan or skull X-ray, cerebral angiography, and a full sepsis workup, including blood studies and urine cultures.

Patient Counseling

Explain the purpose and procedure of diagnostic tests and treatments to the infant’s parents. Provide emotional support, and advise them how they can best be involved in their infant’s care.

REFERENCES

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2011). Urinary tract infection: Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of the initial UTI in febrile infants and children 2 to 24 months. Pediatrics, 128(3), 595–610.

Ardell, S. , Offringa, M., & Soll, R. (2010) . Prophylactic vitamin K for the prevention of vitamin K deficiency bleeding in preterm neonates. Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews, 2010(1). Article No. CD008342.

Fontanel Depression

Depression of the anterior fontanel below the surrounding bony ridges of the skull is a sign of dehydration. A common disorder of infancy and early childhood, dehydration can result from insufficient fluid intake, but typically reflects excessive fluid loss from severe vomiting or diarrhea. It may also reflect insensible water loss, pyloric stenosis, or tracheoesophageal fistula. It’s best to assess the fontanel when the infant is in an upright position and isn’t crying.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If you detect a markedly depressed fontanel, take the infant’s vital signs, weigh him, and check for signs of shock — tachycardia, tachypnea, and cool, clammy skin. If these signs are present, insert an I.V. line and administer fluids. Have size-appropriate emergency equipment on hand. Anticipate oxygen administration. Monitor urine output by weighing wet diapers.

History and Physical Examination

Obtain a thorough patient history from a parent or caretaker, focusing on recent fever, vomiting, diarrhea, and behavioral changes. Monitor the infant’s fluid intake and urine output over the past 24 hours, including the number of wet diapers during that time. Ask about the child’s preillness weight, and compare it to his current weight; weight loss in an infant reflects water loss.

Medical Causes

Dehydration. With mild dehydration (5% weight loss), the anterior fontanel appears slightly depressed. The infant has pale, dry skin and mucous membranes; decreased urine output; a normal or slightly elevated pulse rate; and, possibly, irritability.

Moderate dehydration (10% weight loss) causes slightly more pronounced fontanel depression, along with gray skin with poor turgor, dry mucous membranes, decreased tears, and decreased urine output. The infant has normal or decreased blood pressure, an increased pulse rate and, possibly, lethargy.

Severe dehydration (15% or greater weight loss) may result in a markedly sunken fontanel, along with extremely poor skin turgor, parched mucous membranes, marked oliguria or anuria, lethargy, and signs of shock, such as a rapid, thready pulse; very low blood pressure; and obtundation.

Special Considerations

Continue to monitor the infant’s vital signs and intake and output, and watch for signs of worsening dehydration. Obtain serum electrolyte values to check for an increased or decreased sodium, chloride, or potassium level. If the patient has mild dehydration, provide small amounts of clear fluids frequently or provide an oral rehydration solution. If the infant can’t ingest sufficient fluid, begin I.V. parenteral nutrition.

If the patient has moderate to severe dehydration, your first priority is rapid restoration of extracellular fluid volume to treat or prevent shock. Continue to administer I.V. solution with sodium bicarbonate added to combat acidosis. As renal function improves, administer I.V. potassium replacements. When the infant’s fluid status stabilizes, begin to replace depleted fat and protein stores through diet.

Tests to evaluate dehydration include urinalysis for specific gravity and, possibly, blood tests to determine blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine levels, osmolality, and acid-base status.

Patient Counseling

Explain all procedures and treatments to the infant’s parents, and provide emotional support. Explain

ways to prevent dehydration.

REFERENCES

Alonso-Coello, P. , Irfan, A. , Sola, I. , Gich, I. , Delgado-Noguera, M. , Rigau, D., & Schunemann, H. (2010) . The quality of clinical practice guidelines over the last two decades: A systematic review of guideline appraisal studies . Quality and Safety in Health Care, 19:58.

National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health . (2009) . Diarrhoea and vomiting caused by gastroenteritis. Diagnosis, assessment and management in children younger than 5 years. London, United Kingdom: RCOG Press, 200.

G

Gag Reflex Abnormalities

[Pharyngeal reflex abnormalities]

The gag reflex — a protective mechanism that prevents aspiration of food, fluid, and vomitus — normally can be elicited by touching the posterior wall of the oropharynx with a tongue depressor or by suctioning the throat. Prompt elevation of the palate, constriction of the pharyngeal musculature, and a sensation of gagging indicate a normal gag reflex. An abnormal gag reflex — either decreased or absent — interferes with the ability to swallow and, more important, increases susceptibility to life-threatening aspiration.

An impaired gag reflex can result from a lesion that affects its mediators — cranial nerves (CNs) IX (glossopharyngeal) and X (vagus) or the pons or medulla. It can also occur during a coma, in muscle diseases such as severe myasthenia gravis, or as a temporary result of anesthesia.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If you detect an abnormal gag reflex, immediately stop the patient’s oral intake to prevent aspiration. Quickly evaluate his level of consciousness (LOC). If it’s decreased, place him in a sidelying position to prevent aspiration; if not, place him in Fowler’s position. Have suction equipment at hand.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient (or a family member if the patient can’t communicate) about the onset and duration of swallowing difficulties, if any. Are liquids more difficult to swallow than solids? Is swallowing more difficult at certain times of the day (as occurs in the bulbar palsy associated with myasthenia gravis)? If the patient also has trouble chewing, suspect more widespread neurologic involvement because chewing involves different CNs.

Explore the patient’s medical history for vascular and degenerative disorders. Then, assess his respiratory status for evidence of aspiration and perform a neurologic examination.

Medical Causes

Basilar artery occlusion. Basilar artery occlusion may suddenly diminish or obliterate the gag reflex. It also causes diffuse sensory loss, dysarthria, facial weakness, extraocular muscle palsies, quadriplegia, and a decreased LOC.

Brain stem glioma. Brain stem glioma causes a gradual loss of the gag reflex. Related symptoms reflect bilateral brain stem involvement and include diplopia and facial weakness.

Common involvement of the corticospinal pathways causes spasticity and paresis of the arms and legs as well as gait disturbances.

Bulbar palsy. Loss of the gag reflex reflects temporary or permanent paralysis of muscles supplied by CNs IX and X. Other indicators of bulbar palsy include jaw and facial muscle weakness, dysphagia, loss of sensation at the base of the tongue, increased salivation, possible difficulty articulating and breathing, and fasciculations.

Wallenberg’s syndrome. In Wallenberg’s syndrome, the pharyngeal phase of swallowing and the gag reflex can become impaired. Symptoms usually have an acute onset, occurring within hours to days. The patient may experience loss of pain and temperature sensation ipsilaterally in the orofacial region and contralaterally on the body. Some patients lose their sense of taste on one side of the tongue, while maintaining taste sensations on the other side. Other patients may complain of uncontrollable hiccups, vomiting, rapid involuntary movements of the eyes (nystagmus), problems with balance and gait coordination, ipsilateral ataxia of the arm and leg, and signs of Horner’s syndrome (unilateral ptosis and miosis, hemifacial anhidrosis).

Other Causes

Anesthesia. General and local (throat) anesthesia can produce temporary loss of the gag reflex.

Special Considerations

Continually assess the patient’s ability to swallow. If his gag reflex is absent, provide tube feedings; if it’s merely diminished, try pureed foods. Advise the patient to take small amounts and eat slowly while sitting or in high Fowler’s position. Stay with him while he eats and observe for choking. Remember to keep suction equipment handy in case of aspiration. Keep accurate intake and output records, and assess the patient’s nutritional status daily.

Refer the patient to a therapist to determine his aspiration risk and develop an exercise program to strengthen specific muscles.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic studies, such as swallow studies, a computed tomography scan, magnetic resonance imaging, EEG, lumbar puncture, and arteriography.

Patient Counseling

Advise the patient to eat small amounts slowly while sitting or in high Fowler’s position. Teach him techniques for safe swallowing. Discuss the types and textures of foods that reduce the risk of choking.

Pediatric Pointers

Brain stem glioma is an important cause of an abnormal gag reflex in children.

REFERENCES

Murthy, J. (2010). Neurological complications of dengue infection. Neurology India, 58, 581–584.

Rodenhuis-Zybert, I. A., Wilschut, J., & Smit, J. M. (2010) . Dengue virus life cycle: Viral and host factors modulating infectivity.

Cellular and Molecular Life Science, 67, 2773–2786.

Gait, Bizarre

[Hysterical gait]

A bizarre gait has no obvious organic basis; rather, it’s produced unconsciously by a person with a somatoform disorder (hysterical neurosis) or consciously by a malingerer. The gait has no consistent pattern. It may mimic an organic impairment, but characteristically has a more theatrical or bizarre quality with key elements missing, such as a spastic gait without hip circumduction, or leg “paralysis” with normal reflexes and motor strength. Its manifestations may include wild gyrations, exaggerated stepping, leg dragging, or mimicking unusual walks such as that of a tightrope walker.

History and Physical Examination

If you suspect that the patient’s gait impairment has no organic cause, begin to investigate other possibilities. Ask the patient when he first developed the impairment and whether it coincided with a stressful period or event, such as the death of a loved one or loss of a job. Ask about associated symptoms, and explore reports of frequent unexplained illnesses and multiple physician’s visits. Subtly try to determine if the patient will gain anything from malingering, for instance, added attention or an insurance settlement.

Begin the physical examination by testing the patient’s reflexes and sensorimotor function, noting abnormal response patterns. To quickly check his reports of leg weakness or paralysis, perform a test for Hoover’s sign: Place the patient in the supine position and stand at his feet. Cradle a heel in each of your palms and rest your hands on the table. Ask the patient to raise the affected leg. In true motor weakness, the heel of the other leg will press downward; in hysteria, this movement will be absent. As a further check, observe the patient for normal movements when he’s unaware of being watched.

Medical Causes

Conversion disorder. Conversion disorder is a rare somatoform disorder, in which a bizarre gait or paralysis may develop after severe stress and isn’t accompanied by other symptoms. The patient typically shows indifference toward his impairment.

Malingering. Malingering is a rare cause of bizarre gait, in which the patient may also complain of a headache and chest and back pain.

Somatization disorder. Bizarre gait is one of many possible somatic complaints. The patient may exhibit any combination of pseudoneurologic signs and symptoms — fainting, weakness, memory loss, dysphagia, visual problems (diplopia, vision loss, blurred vision), loss of voice, seizures, and bladder dysfunction. He may also report pain in the back, joints, and extremities (most commonly the legs) and complaints in almost any body system. For example, characteristic GI complaints include pain, bloating, nausea, and vomiting.

The patient’s reflexes and motor strength remain normal, but peculiar contractures and arm or leg rigidity may occur. His reputed sensory loss doesn’t conform to a known sensory dermatome. In some cases, he won’t stand or walk (astasia/abasia), remaining bedridden although still able to move his legs in bed.

Special Considerations

A full neurologic workup may be necessary to completely rule out an organic cause of the patient’s abnormal gait. Remember, even though bizarre gait has no organic basis, it’s real to the patient (unless, of course, he’s malingering). Avoid expressing judgment on the patient’s actions or motives; you’ll need to be supportive and reinforce positive progress. Because muscle atrophy and bone demineralization can develop in a bedridden patient, encourage ambulation and resumption of normal activities. Consider a referral for psychiatric counseling as appropriate.

Patient Counseling

Instruct the patient in the use of assistive devices, as necessary. Review safety measures such as wearing proper footwear.

Pediatric Pointers

Bizarre gait is rare in patients younger than age 8. More common in prepubescence, it usually results from conversion disorder.

REFERENCES

Debi, R., Mor, A., Segal, G., Segal, O., Agar, G., Debbi, E., … Elbaz A. (2011). Correlation between single limb support phase and selfevaluation questionnaires in knee osteoarthritis populations. Disability and Rehabilitation, 33, 1103–1109.

Elbaz, A. , Mor, A . , Segal, O. , Agar, G. , Halperin, N. , Haim, A., … Debi, R. (2012) . Can single limb support objectively assess the functional severity of knee osteoarthritis? Knee, 12(1), 32–35.

Gait, Propulsive

[Festinating gait]

Propulsive gait is characterized by a stooped, rigid posture — the patient’s head and neck are bent forward; his flexed, stiffened arms are held away from the body; his fingers are extended; and his knees and hips are stiffly bent. During ambulation, this posture results in a forward shifting of the body’s center of gravity and consequent impairment of balance, causing increasingly rapid, short, shuffling steps with involuntary acceleration (festination) and lack of control over forward motion (propulsion) or backward motion (retropulsion). (See Identifying Gait Abnormalities.)

Identifying Gait Abnormalities