- •CONTENTS

- •INTRODUCTION

- •1 Getting Started

- •Better, Cheaper, Easier

- •Who This Book Is For

- •What Kind of Digital Film Should You Make?

- •2 Writing and Scheduling

- •Screenwriting

- •Finding a Story

- •Structure

- •Writing Visually

- •Formatting Your Script

- •Writing for Television

- •Writing for “Unscripted”

- •Writing for Corporate Projects

- •Scheduling

- •Breaking Down a Script

- •Choosing a Shooting Order

- •How Much Can You Shoot in a Day?

- •Production Boards

- •Scheduling for Unscripted Projects

- •3 Digital Video Primer

- •What Is HD?

- •Components of Digital Video

- •Tracks

- •Frames

- •Scan Lines

- •Pixels

- •Audio Tracks

- •Audio Sampling

- •Working with Analog or SD Video

- •Digital Image Quality

- •Color Sampling

- •Bit Depth

- •Compression Ratios

- •Data Rate

- •Understanding Digital Media Files

- •Digital Video Container Files

- •Codecs

- •Audio Container Files and Codecs

- •Transcoding

- •Acquisition Formats

- •Unscientific Answers to Highly Technical Questions

- •4 Choosing a Camera

- •Evaluating a Camera

- •Image Quality

- •Sensors

- •Compression

- •Sharpening

- •White Balance

- •Image Tweaking

- •Lenses

- •Lens Quality

- •Lens Features

- •Interchangeable Lenses

- •Never Mind the Reasons, How Does It Look?

- •Camera Features

- •Camera Body Types

- •Manual Controls

- •Focus

- •Shutter Speed

- •Aperture Control

- •Image Stabilization

- •Viewfinder

- •Interface

- •Audio

- •Media Type

- •Wireless

- •Batteries and AC Adaptors

- •DSLRs

- •Use Your Director of Photography

- •Accessorizing

- •Tripods

- •Field Monitors

- •Remote Controls

- •Microphones

- •Filters

- •All That Other Stuff

- •What You Should Choose

- •5 Planning Your Shoot

- •Storyboarding

- •Shots and Coverage

- •Camera Angles

- •Computer-Generated Storyboards

- •Less Is More

- •Camera Diagrams and Shot Lists

- •Location Scouting

- •Production Design

- •Art Directing Basics

- •Building a Set

- •Set Dressing and Props

- •DIY Art Direction

- •Visual Planning for Documentaries

- •Effects Planning

- •Creating Rough Effects Shots

- •6 Lighting

- •Film-Style Lighting

- •The Art of Lighting

- •Three-Point Lighting

- •Types of Light

- •Color Temperature

- •Types of Lights

- •Wattage

- •Controlling the Quality of Light

- •Lighting Gels

- •Diffusion

- •Lighting Your Actors

- •Interior Lighting

- •Power Supply

- •Mixing Daylight and Interior Light

- •Using Household Lights

- •Exterior Lighting

- •Enhancing Existing Daylight

- •Video Lighting

- •Low-Light Shooting

- •Special Lighting Situations

- •Lighting for Video-to-Film Transfers

- •Lighting for Blue and Green Screen

- •7 Using the Camera

- •Setting Focus

- •Using the Zoom Lens

- •Controlling the Zoom

- •Exposure

- •Aperture

- •Shutter Speed

- •Gain

- •Which One to Adjust?

- •Exposure and Depth of Field

- •White Balancing

- •Composition

- •Headroom

- •Lead Your Subject

- •Following Versus Anticipating

- •Don’t Be Afraid to Get Too Close

- •Listen

- •Eyelines

- •Clearing Frame

- •Beware of the Stage Line

- •TV Framing

- •Breaking the Rules

- •Camera Movement

- •Panning and Tilting

- •Zooms and Dolly Shots

- •Tracking Shots

- •Handholding

- •Deciding When to Move

- •Shooting Checklist

- •8 Production Sound

- •What You Want to Record

- •Microphones

- •What a Mic Hears

- •How a Mic Hears

- •Types of Mics

- •Mixing

- •Connecting It All Up

- •Wireless Mics

- •Setting Up

- •Placing Your Mics

- •Getting the Right Sound for the Picture

- •Testing Sound

- •Reference Tone

- •Managing Your Set

- •Recording Your Sound

- •Room Tone

- •Run-and-Gun Audio

- •Gear Checklist

- •9 Shooting and Directing

- •The Shooting Script

- •Updating the Shooting Script

- •Directing

- •Rehearsals

- •Managing the Set

- •Putting Plans into Action

- •Double-Check Your Camera Settings

- •The Protocol of Shooting

- •Respect for Acting

- •Organization on the Set

- •Script Supervising for Scripted Projects

- •Documentary Field Notes

- •What’s Different with a DSLR?

- •DSLR Camera Settings for HD Video

- •Working with Interchangeable Lenses

- •What Lenses Do I Need?

- •How to Get a Shallow Depth of Field

- •Measuring and Pulling Focus

- •Measuring Focus

- •Pulling Focus

- •Advanced Camera Rigging and Supports

- •Viewing Video on the Set

- •Double-System Audio Recording

- •How to Record Double-System Audio

- •Multi-Cam Shooting

- •Multi-Cam Basics

- •Challenges of Multi-Cam Shoots

- •Going Tapeless

- •On-set Media Workstations

- •Media Cards and Workflow

- •Organizing Media on the Set

- •Audio Media Workflow

- •Shooting Blue-Screen Effects

- •11 Editing Gear

- •Setting Up a Workstation

- •Storage

- •Monitors

- •Videotape Interface

- •Custom Keyboards and Controllers

- •Backing Up

- •Networked Systems

- •Storage Area Networks (SANs) and Network-Attached Storage (NAS)

- •Cloud Storage

- •Render Farms

- •Audio Equipment

- •Digital Video Cables and Connectors

- •FireWire

- •HDMI

- •Fibre Channel

- •Thunderbolt

- •Audio Interfaces

- •Know What You Need

- •12 Editing Software

- •The Interface

- •Editing Tools

- •Drag-and-Drop Editing

- •Three-Point Editing

- •JKL Editing

- •Insert and Overwrite Editing

- •Trimming

- •Ripple and Roll, Slip and Slide

- •Multi-Camera Editing

- •Advanced Features

- •Organizational Tools

- •Importing Media

- •Effects and Titles

- •Types of Effects

- •Titles

- •Audio Tools

- •Equalization

- •Audio Effects and Filters

- •Audio Plug-In Formats

- •Mixing

- •OMF Export

- •Finishing Tools

- •Our Software Recommendations

- •Know What You Need

- •13 Preparing to Edit

- •Organizing Your Media

- •Create a Naming System

- •Setting Up Your Project

- •Importing and Transcoding

- •Capturing Tape-based Media

- •Logging

- •Capturing

- •Importing Audio

- •Importing Still Images

- •Moving Media

- •Sorting Media After Ingest

- •How to Sort by Content

- •Synchronizing Double-System Sound and Picture

- •Preparing Multi-Camera Media

- •Troubleshooting

- •14 Editing

- •Editing Basics

- •Applied Three-Act Structure

- •Building a Rough Cut

- •Watch Everything

- •Radio Cuts

- •Master Shot—Style Coverage

- •Editing Techniques

- •Cutaways and Reaction Shots

- •Matching Action

- •Matching Screen Position

- •Overlapping Edits

- •Matching Emotion and Tone

- •Pauses and Pull-Ups

- •Hard Sound Effects and Music

- •Transitions Between Scenes

- •Hard Cuts

- •Dissolves, Fades, and Wipes

- •Establishing Shots

- •Clearing Frame and Natural “Wipes”

- •Solving Technical Problems

- •Missing Elements

- •Temporary Elements

- •Multi-Cam Editing

- •Fine Cutting

- •Editing for Style

- •Duration

- •The Big Picture

- •15 Sound Editing

- •Sounding Off

- •Setting Up

- •Temp Mixes

- •Audio Levels Metering

- •Clipping and Distortion

- •Using Your Editing App for Sound

- •Dedicated Sound Editing Apps

- •Moving Your Audio

- •Editing Sound

- •Unintelligible Dialogue

- •Changes in Tone

- •Is There Extraneous Noise in the Shot?

- •Are There Bad Video Edits That Can Be Reinforced with Audio?

- •Is There Bad Audio?

- •Are There Vocal Problems You Need to Correct?

- •Dialogue Editing

- •Non-Dialogue Voice Recordings

- •EQ Is Your Friend

- •Sound Effects

- •Sound Effect Sources

- •Music

- •Editing Music

- •License to Play

- •Finding a Composer

- •Do It Yourself

- •16 Color Correction

- •Color Correction

- •Advanced Color Controls

- •Seeing Color

- •A Less Scientific Approach

- •Too Much of a Good Thing

- •Brightening Dark Video

- •Compensating for Overexposure

- •Correcting Bad White Balance

- •Using Tracks and Layers to Adjust Color

- •Black-and-White Effects

- •Correcting Color for Film

- •Making Your Video Look Like Film

- •One More Thing

- •17 Titles and Effects

- •Titles

- •Choosing Your Typeface and Size

- •Ordering Your Titles

- •Coloring Your Titles

- •Placing Your Titles

- •Safe Titles

- •Motion Effects

- •Keyframes and Interpolating

- •Integrating Still Images and Video

- •Special Effects Workflow

- •Compositing 101

- •Keys

- •Keying Tips

- •Mattes

- •Mixing SD and HD Footage

- •Using Effects to Fix Problems

- •Eliminating Camera Shake

- •Getting Rid of Things

- •Moving On

- •18 Finishing

- •What Do You Need?

- •Start Early

- •What Is Mastering?

- •What to Do Now

- •Preparing for Film Festivals

- •DIY File-Based Masters

- •Preparing Your Sequence

- •Color Grading

- •Create a Mix

- •Make a Textless Master

- •Export Your Masters

- •Watch Your Export

- •Web Video and Video-on-Demand

- •Streaming or Download?

- •Compressing for the Web

- •Choosing a Data Rate

- •Choosing a Keyframe Interval

- •DVD and Blu-Ray Discs

- •DVD and Blu-Ray Compression

- •DVD and Blu-Ray Disc Authoring

- •High-End Finishing

- •Reel Changes

- •Preparing for a Professional Audio Mix

- •Preparing for Professional Color Grading

- •Putting Audio and Video Back Together

- •Digital Videotape Masters

- •35mm Film Prints

- •The Film Printing Process

- •Printing from a Negative

- •Direct-to-Print

- •Optical Soundtracks

- •Digital Cinema Masters

- •Archiving Your Project

- •GLOSSARY

- •INDEX

Chapter 3 n Digital Video Primer |

55 |

Audio Container Files and Codecs

When audio is stored in a separate file without video, it is usually stored in one of several standard PCM formats: WAV, AIFF, or SDII. These are all uncompressed formats, and all fall under the category of PCM audio.

As long as you maintain the same sampling rate, conversions between different PCM audio file types are lossless. MP3 is a highly compressed audio format that offers very small file sizes and good sound quality, despite the compression. Typically, MP3 is not considered a great file format for editing audio in films. MP4 (sometimes called MPEG-4 because both MP3 and MP4 are part of the MPEG video specification) is a successor to MP3 that offers better compression without degrading quality. A 128K MP4 file delivers 160K MP3 quality in a much smaller space. AAC format (which you might have encountered in downloads from the iTunes Music Store) is just an MP4 audio file with a special digital-rights-management (DRM) “wrapper.”

Dolby AC-3 audio consists of 5.1 channels of Dolby Digital Surround Sound. Typically, the 5.1 channels are designed to create a surround environment in a movie theater, so the channels are laid out as left, center, right, left surround, right surround, and the .1 channel is an optional subwoofer track for low-frequency sounds. HD video formats offer AC-3 5.1 sound. DTS and SDDS audio are other forms of surround sound used for feature films. (You’ll find more about surround sound formats in Chapter 18.)

Transcoding

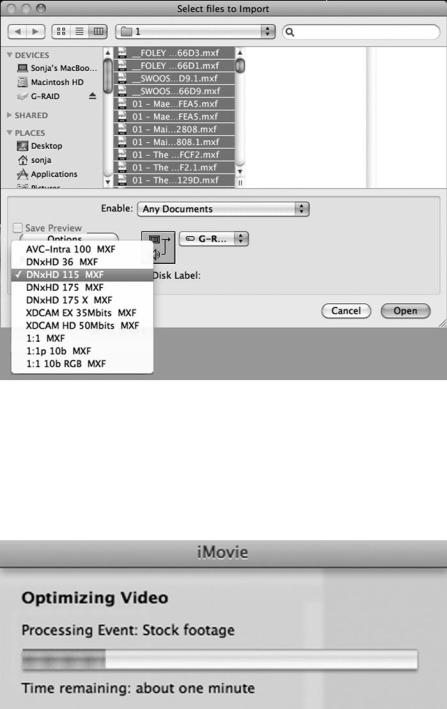

The process of converting a piece of media from one codec to another is called transcoding. Most video container file formats can support a wide range of different codecs. So, for example, you can have a .MOV file that uses the H.264 codec, and you can also have a .MOV file that uses the Avid DNxHD codec. If you shoot footage with a camera using H.264, drag it to your desktop, and then convert it to DNxHD to work with Avid Media Composer, you are transcoding your original media (see Figure 3.13). The file itself will still be a .MOV file, but you will have fundamentally changed your media.

Transcoding can be a hardware-based or a software-based process and whenever you move digital video around, you run the chance of transcoding your media. Transcoding isn’t necessarily bad; in fact, it’s often necessary and beneficial, but you should make sure you are not unintentionally transcoding your media to a lower quality codec.

So how and when does transcoding happen? The first way has to do with how you move media from your camera to your computer. If you are dragging and dropping files from a disc or hard drive to your computer’s hard drive, you are not transcoding. But if you are using a cable running from your camera or videotape deck to a video input on your computer or video card, then you need to be careful. If you shoot HD, then you need to make sure that the chain of connectors and cables between your camera and your computer is all digital. If your camera has an analog video-out connector, such as S-video, then simply by sending your video out through this connector you are transcoding it into an analog signal. Then when it gets to your video card or connector on the computer, it is being transcoded back into a digital signal. It’s true that you may not see a huge difference in the resulting image, but it’s better to avoid transcoding your media more often than is necessary for your workflow.

56 The Digital Filmmaking Handbook, 4E

Figure 3.13

The Import Files window in Media Composer 5 offers a selection of codecs to choose from as you transcode your media.

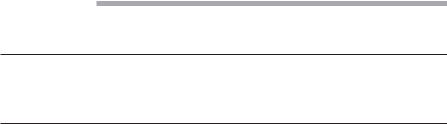

The second way that transcoding happens is when you bring your video files into your editing software. Typically, if you use the Import command to bring video into an editing app, you are basically telling the editing software to transcode your footage into a codec that the application prefers. Higher-end applications make you aware of this process, but more consumeroriented apps, such as Apple iMovie, will do this automatically (see Figure 3.14). Basically, if you try to bring media into your editing software, and it takes a while to do so, you can probably assume the app is transcoding your media.

Figure 3.14

Some apps like Apple iMovie automatically transcode your media when you bring it into the application.

Chapter 3 n Digital Video Primer |

57 |

The third way that transcoding happens is when you export media from your editing application to a file for viewing. Typically, you’ll create several different masters at the end of your editing process: a high-resolution master for screenings, a low-res master for Web streaming, and several other options in-between. We’ll discuss how to transcode your final cut for various delivery formats in Chapter 18.

Going Native

When editing applications offer “native support” for various types of media, that means you will be able to edit those formats without the need for transcoding.

Acquisition Formats

Video footage is almost always acquired by a camera (unless it is computer-generated), and every video camera records to a specific, usually proprietary, format. Because video cameras are constantly being updated and developed, acquisition formats change frequently. Also, be aware that some higher-end cameras can record more than one format.

Here is a list of what’s out there for digital video acquisition at the time of this writing:

nDV is still out there, but fading fast. This 25Mbps SD format was designed to work with FireWire-based DV video (Digital8, DV, DVCAM, or DVCPro), and it uses the hardware DV codec in the camera or video deck to compress and decompress the video on DV tape stock.

nHDV is the “consumer” HD format and is much more compressed than the other HD formats, resulting in a lower quality image. As a result, it also has a low bit rate (about 25Mbps), which means it can be transferred or captured via FireWire. HDV camcorders use the MPEG-2 codec to record 4:2:0, 8-bit color images on either DV tape or SD cards.

nDVCPRO-HD is technically part of the DV family but employs a more complex DV encoding algorithm and higher bit rates (40–100Mbps) resulting in high-quality 4:2:2, 8-bit HD video.

nMPEG-IMX is a 4:2:2, 8-bit format that uses intraframe compression and records to optical discs or digital videotape. It is a popular ENG (electronic news gathering) format for TV, news, and so on.

nXDCAM HD from Sony is a 4:2:2, 8-bit direct-to-disc professional HD format that uses MPEG-2 compression to record to optical discs or memory cards.

nAVCHD is a tapeless MPEG-4–based HD format developed by Panasonic and Sony and aimed at consumer-grade HD cameras. It offers 4:2:0 8-bit color sampling, and it is used by several different types of cameras, including the Panasonic AVCCAM line and most DSLR cameras that shoot HD.

nAVC-Intra is a 4:2:0, 10-bit MPEG-4–based HD codec that comes in either a 100Mbps or 50Mbps format. Developed by Panasonic, this format is often used in conjunction with proprietary P2 cards.

nHDCAM is a 4:4:4, 10-bit HD codec used by the Sony professional family of camcorders that uses proprietary DCT-based compression.

58 The Digital Filmmaking Handbook, 4E

nRed R3D is a high-quality digital video format that seeks to compete with 35mm film, offering 2K, 3K, and 4K resolutions and using the proprietary R3D codec.

nApple Pro Res started out as an intermediate codec used for editing, but with the introduction of the Arri Alexa digital cinema camera, it is now also an acquisition format.

nArriRAW is a digital cinema codec used by the Arri line of cameras.

Intermediate Formats

After you acquire your HD video, you’ll bring it into your computer in order to edit it. Some editing applications use intermediate formats for optimized playback during editing. Most intermediate formats are proprietary, and although you are not always required to transcode your camera-original media into an intermediate format, usually the editing process works better if you do. The Apple ProRes family of intermediate codecs is designed to work with Final Cut Pro, and the Avid DNxHD family of intermediate codecs are designed to work with Avid’s line of editing applications, including Media Composer 5. Both offer several quality levels available, including an “uncompressed” codec. More about intermediate formats in Chapter 13, “Preparing to Edit.”

What If I’m Shooting with My Smart Phone?

Sometimes, it’s impossible to resist the instant gratification of shooting with a consumer device such as an iPhone or a point-and-shoot camera. Bear in mind that at the time of this writing only the newest devices can shoot full HD video. Here are some strategies for dealing with “low-end” media.

nStay low. If you shoot low-quality consumer video and your goal is to create a video for the Web, then you might want to consider sticking with lower-end consumer technology throughout your project. Rather than upgrading (transcoding) this footage into high-res HD, it’s easier and cheaper to just use a lower-end editing application like iMovie and finish with a Web-oriented codec such as Sorenson.

nMix it up. If most of your project is HD, but you have a few shots that you want to incorporate that were shot on a low-quality consumer camera, the best strategy is to transcode this media into the intermediate format that you are using to edit. (Your editing app should be able to do this easily for you.) Then use the FX capabilities of your editing software to integrate this footage with your HD footage. For more about how to use basic special effects to mix HD and SD footage, take a look at Chapter 17.

Unscientific Answers to Highly Technical Questions

So back to those questions in the beginning: What is the best way to shoot my project? Should I shoot 24P? What is the difference between 1080 and 720 HD? What type of digital video will look most like film?

Chapter 3 n Digital Video Primer |

59 |

Here are some unscientific answers:

nShoot the best quality you can. Why? Because it will look better. Have you ever watched a tiny thumbnail-sized trailer of the latest Hollywood blockbuster? It looks pretty good, even though it’s highly compressed. Most likely, it was shot on film or a digital cinema format. For whatever reasons, higher-quality acquisition formats hold up better even when they are transcoded into a low-quality delivery format.

nDon’t let production values stop your production. Why not? Because if your story is strong, no one will care what it looks like. Most people stop noticing things like compression artifacts a minute or two into the story. Yes, a beautiful-looking film is compelling and some may disagree, but we feel that story is more important than beauty. Great shots are the icing on the cake, but the story is the cake. In a dream world, you have both, but a great story can stand alone. If you don’t believe this, watch some documentaries. Documentary subject matter very rarely allows for ideal shooting. But with a subject with a compelling story, this simply doesn’t matter.

n720 or 1080? Extreme video nerds are going to put a price on our head for saying this, but it doesn’t really matter whether you choose 720 or 1080. They’re both excellent. If you work for a TV network that requires 720, then you should shoot 720. Or if the camera you love only shoots 720, then shoot 720. If not, you will probably shoot 1080 because it sounds better, and that’s what most people are choosing if they have a choice.

n24p? If you are making a film-like project, whether it’s a feature length or a short, you might as well shoot 24p. The things that made it difficult to deal with in the past have faded away. Plus, the whole film world is set up to expect and work with 24fps. And even if you can’t see a difference between 24fps and 30fps, you’ll at least be saving about 20 percent in terms of storage space on your hard drives thanks to the lower frame rate.

nGo with the flow. If you are making a TV project in the U.S., you might as well stick to standard 29.97fps because the American TV world is set up to expect and work with that frame rate. If you are making a project destined for computers or the Web, choose 30fps because that’s what is expected for the Internet. If you are making a video project outside the U.S., you should use the standard European frame rate of 25fps. If you are shooting a feature film, shoot 24fps. If you want your TV/Web project to look like film, you can do more with some well-chosen postproduction processes like color grading than a lower frame rate will ever come close to, in terms of creating a “film look.”

nDigital cinema? If you can afford it, yes! But just remember that every step of the postproduction pipeline is going to cost more, not just the camera. Choosing a digital cinema format that records to SD cards could help you save a few bucks, though.

nWhat looks most like film? A film look is based on more than high image resolution and low frame rates. It’s also the lens, the camera itself, shot design, production design, lighting, locations, quality of acting, and many other variables. And that’s exactly what we’re going to talk about in the upcoming chapters.