ppl_05_e2

.pdf

ID: 3658

Customer: Oleg Ostapenko E-mail: ostapenko2002@yahoo.com

Customer: Oleg Ostapenko E-mail: ostapenko2002@yahoo.com

CHAPTER 11: STABILITY

Any keel surface (side surface) above the Centre of Gravity (C of G), such as the fuselage sides or fn, will, during a side slip, set up forces creating a restoring moment which will tend to return the aircraft to the wings-level attitude.

(See Figure 11.21)

Most low-wing aircraft possess pronounced dihedral to give them lateral stability. The

Piper PA28 Warrior pictured in Figure 11.22 has a wing of marked positive dihedral.

Figure 11.22 Positive dihedral on the Piper PA28 Warrior.

High-Wing Aircraft.

High-wing aircraft have such a degree of inherent lateral stability that their wing dihedral angle is normally very small. You can see the difference between the dihedral on a high-wing Cessna 172 and the low wing Piper PA 28 in Figure 11.23.

Figure 11.23 The difference in dihedral between low and high wing aircraft.

237

Order: 6026

Customer: Oleg Ostapenko E-mail: ostapenko2002@yahoo.com

Customer: Oleg Ostapenko E-mail: ostapenko2002@yahoo.com

CHAPTER 11: STABILITY

A high-wing aircraft

requires less dihedral,

because the keel surfaces above the C of G, together with the pendulum effect, give the aircraft inherent lateral stability.

With a high-wing aircraft, during a sideslip, the sideways component of the relative airfow fows up around the fuselage on the lower wing, increasing its angle of attack and, thus, its lift, and fows down towards the higher wing decreasing its angle of attack and lift. This phenomenon contributes towards positive lateral stability (See Figure 11.24).

Figure 11.24 Lateral Stability characteristics of a high wing. Relative airflow in a sideslip.

The fuselage and side (or keel) surfaces above the C of G also exert a stabilising effect.

In addition, high wing aircraft produce a stabilising moment, contributing to their lateral stability, as a result of the pendulum effect, as depicted in Figure 11.25.

Figure 11.25 Lateral Stability characteristics of a high-wing: the Pendulum Effect.

Swept Back Wings.

The study of high speed fight is not a requirement for the Private Pilot’s Licence.

However, you should know that sweepback also contributes to positive lateral stability, because, during a sideslip, the lower wing effectively presents a greater span, and, thus, a greater aspect ratio to the relative airfow. The lower wing will therefore generate more lift giving rise to a restoring moment which tends to return the aircraft to the wings-level attitude. (See Figure 11.26.)

238

ID: 3658

Customer: Oleg Ostapenko E-mail: ostapenko2002@yahoo.com

Customer: Oleg Ostapenko E-mail: ostapenko2002@yahoo.com

CHAPTER 11: STABILITY

Lateral stability is reinforced by sweep-back.

Figure 11.26 Lateral Stability characteristics of a swept-back wing.

Anhedral.

Jet aircraft with a wing of pronounced sweep-back may actually posses too much positive lateral stability. Such aircraft may, consequently have a wing with anhedral. Anhedral is negative dihedral and reduces lateral stability. (See Figure 11.27).

Figure 11.27 Anhedral reduces lateral stability.

The Effect of Flaps and Power on Lateral Stability.

You will recall that faps reduce longitudinal stability because of their infuence on downwash. Lateral stability is also reduced when partial span faps are deployed.

The deployment of partial-span faps causes the lift on the inboard section of the wing to increase relative to the wing’s outer section, as depicted in Figure 11.28. This phenomenon, which moves the spanwise centre of pressure inboard, reduces the spanwise moment arm. Consequently, during a sideslip, any modifcation of the lift force occurs closer inboard, reducing the correcting moment. The overall effect of deploying fap, then, is to reduce lateral stability.

239

Order: 6026

Customer: Oleg Ostapenko E-mail: ostapenko2002@yahoo.com

Customer: Oleg Ostapenko E-mail: ostapenko2002@yahoo.com

CHAPTER 11: STABILITY

Lateral stability is reduced

when flaps are selected

because the Centre of Pressure moves inboard.

The propeller slipstream, at high engine power settings and low aircraft forward speed, also reduces lateral stability as the inboard wing sections become more effective than the outer sections in generating lift force because of the energising effect of the slipstream. At low forward speed, of course, the ailerons are less effective.

Figure 11.28 The point through which the lift force acts moves inboard with flaps extended.

The reduction in the lateral stability is most critical when the effects of fap, propeller slipstream and low forward speed are combined. The reduction in lateral stability would be conveyed to the pilot as a reduction in the control movement required to manoeuvre the aircraft in roll.

Figure 11.29 High power settings at low forward speed reduce lateral stability.

240

ID: 3658

Customer: Oleg Ostapenko E-mail: ostapenko2002@yahoo.com

Customer: Oleg Ostapenko E-mail: ostapenko2002@yahoo.com

CHAPTER 11: STABILITY

DIRECTIONAL STABILITY.

Introduction.

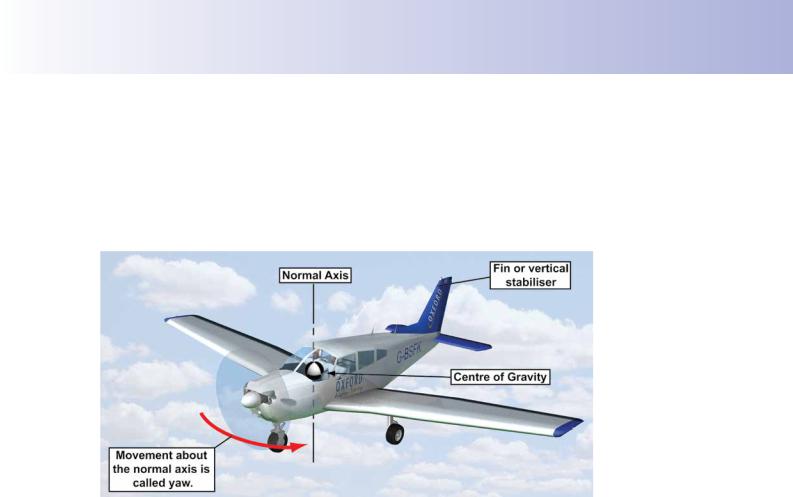

Directional stability is stability about the vertical, or normal, axis. Movement about this axis is called yaw, so vertical stability may also be defned as stability in the yawing plane. The tail fn or vertical stabiliser is the surface which contributes most to directional stability. See Figure 11.30.

Figure 11.30 Directional stability is stability about the normal axis, in the yawing plane.

An aircraft possesses positive directional stability if it tends to recover from a disturbance in the yawing plane without any control input from the pilot. Most light aircraft have pronounced directional stability, their nose weathercocking readily into the relative airfow.

Weathercocking is a term which likens the directional stability of an aircraft to the mode of operation of weathercocks on church steeples. A weathercock swings into the wind because the greater part of its side (keel) surfaces are behind its point of rotation. An aircraft rotates about its centre of gravity; therefore, as the greater area of its keel surface is behind the centre of gravity, the aircraft is directionally stable.

The Tail Fin or Vertical Stabiliser.

The tail fn is a symmetrical aerofoil. Therefore, with a relative airfow from straight ahead, the fn will be at 0º angle of attack, as shown in Figure 11.31, and no aerodynamic force, except drag, will be produced by the fn.

But if the aircraft is disturbed in the yawing plane, the angle of attack at the fn increases, creating an aerodynamic force opposing the yaw, thus providing a correcting turning moment about the aircraft’s Centre of Gravity (C of G). The nose of the aircraft will, therefore, swing back to face the relative airfow, and the aircraft will have displayed positive directional stability. (See Figure 11.32).

Note that when an aircraft is disturbed in the yawing plane, it is moving crabwise through the air, with the relative airfow striking its keel surfaces at an angle. This movement is referred to as slip or skid. In this fight condition, the weathercocking effect will also cause the aircraft to tend to swing back to face the relative airfow.

241

Order: 6026

Customer: Oleg Ostapenko E-mail: ostapenko2002@yahoo.com

Customer: Oleg Ostapenko E-mail: ostapenko2002@yahoo.com

CHAPTER 11: STABILITY

Figure 11.31 The tail fin is a symmetrical aerofoil, exerting no aerodynamic force when the aircraft faces the relative airflow.

Directional stability is provided by the fin.

Figure 11.32 The tail fin provides directional stability when the aircraft is disturbed in the yawing plane.

The Effectiveness of the Tail Fin.

The correcting turning moment produced by the tail fn which gives an aircraft directional stability depends on three factors. They are:

•The angle of attack caused by the disturbance in the yawing plane.

•The side-surface or area of the fn, and effciency of the fn’s aerofoil section.

•The length of the moment arm between the fn and the C of G.

A small fn at the end of a long fuselage may be just as effcient in giving an aircraft directional stability as a large fn at the end of a short fuselage.

242

ID: 3658

Customer: Oleg Ostapenko E-mail: ostapenko2002@yahoo.com

Customer: Oleg Ostapenko E-mail: ostapenko2002@yahoo.com

CHAPTER 11: STABILITY

You may have seen aircraft with more than one fn, as depicted in Figure 11.33. This feature indicates that the aircraft, for design or aerodynamic reasons, requires a greater fn surface area than a single fn can provide. (e.g. F14 Tomcat, F15 Eagle), or,as in the case of the Miles Gemini below, the designer opts to take advantage of increased fn/rudder effectiveness by placing them in the propeller slipstream.

Figure 11.33 An aeroplane with two tail fins.

The stabilising action of the tail fn can be supplemented by the use of dorsal and ventral fns, as illustrated in Figure 11.34, Dorsal and ventral fns are small aerofoil sections positioned above and below the fuselage, respectively, and are used to increase the keel area aft of the aircraft’s C of G.

Figure 11.34 Dorsal and Ventral fins.

THE INTERRELATIONSHIP BETWEEN LATERAL AND DIRECTIONAL STABILITY.

Having considered lateral and directional stability separately, we now need to examine why an aircraft’s lateral and directional rotation about its C of G are not independent of each other. There is an important interrelationship between an aircraft’s displacement in the rolling plane and its displacement in the yawing plane.

A displacement in the yawing plane will always infuence an aircraft’s motion in the rolling plane, and vice versa.

Movements in the rolling and yawing planes are interrelated.

243

Order: 6026

Customer: Oleg Ostapenko E-mail: ostapenko2002@yahoo.com

Customer: Oleg Ostapenko E-mail: ostapenko2002@yahoo.com

CHAPTER 11: STABILITY

An initial roll will be

followed by a sideslip

towards the lower wing and then yaw in the same direction as roll.

Initial Roll Followed by Yaw.

If a pilot selects an angle of bank with ailerons alone, without making any further control movements, the aircraft responds initially by rolling about its longitudinal axis. The displacement of the ailerons which induces the roll generates increased lift on the up-going wing, while the lift on the down-going wing decreases. As you have learnt in the early chapters of this book, an increase in lift is always accompanied by an increase in drag. Therefore, the up-going wing will be held back relative to the down-going wing, causing the aircraft to yaw towards the upper wing. This initial yaw following a roll induced by ailerons alone is called adverse aileron yaw or adverse yaw. The initial roll, therefore, has led to yaw. If there is no further control input from the pilot, subsequent developments will be as follows.

•The aircraft will slip towards the lower wing, and the side component of the relative airfow will, consequently, strike the aircraft’s keel surfaces. In a conventional aircraft, the keel surfaces behind the centre of gravity (C of G) are of a greater area than the area of the keel surfaces forward of the C of G, and, therefore, because of the sideslip, the aircraft will now yaw in the direction of the lower wing.

•The yaw towards the lower wing naturally causes the higher wing, on the outside of the turn, to move faster than the lower wing. The velocity of the airfow over the higher wing will, thus, be greater than that over the lower

wing, further increasing the lift differential between the two wings (Lift = CL ½ ρ v2 S) so as to reinforce the rolling movement.

•More roll will induce more yaw which will reinforce the roll, and so on.

Thus, the original roll frst caused yaw against the direction of roll followed by yaw in the direction of roll. The yaw in the direction of roll mutually reinforced each other and, if not halted, by the pilot’s intervention, lead to the aircraft entering a spiral dive.

(See Figure 11.35)

Figure 11.35 Rolling and yawing actions mutually reinforce themselves in the same direction and lead to a spiral dive.

244

ID: 3658

Customer: Oleg Ostapenko E-mail: ostapenko2002@yahoo.com

Customer: Oleg Ostapenko E-mail: ostapenko2002@yahoo.com

CHAPTER 11: STABILITY

We see, then, that a movement about the longitudinal axis always affects an aircraft’s motion about the normal axis. An initial roll will, thus, be followed by yaw, unless the pilot intervenes by making an appropriate control movement.

An aircraft’s degree of directional stability compared to its level of lateral stability will infuence the extent to which a rolling movement will induce a yawing movement. If the aircraft is very stable directionally (as most light aircraft are), with a large fn

(vertical stabiliser) and rudder surface, the tendency for the aircraft to yaw in the direction of slip will be very marked.

Initial Yaw Followed by Roll.

If the aircraft is displaced in the yawing plane (that is, directionally, about its normal axis), one wing will move forward relative to the other. Unless the pilot intervenes, the forward moving wing will generate a greater lift force than the rearwards moving wing. The main reason for this is that, during the initial yaw, the velocity of the airfow over the forward-moving wing will be greater than that over the rearwards-moving wing, thus increasing lift, (Lift = CL ½ ρ v2 S).

Consequently, the aircraft will begin to roll in the direction of yaw. The roll will induce more yaw, which in turn will cause more roll, and so on. Again, unless the pilot intervenes, a spiral dive will ensue. An initial yaw, then, will be followed by roll in the same direction as yaw.

The Stability Characteristics of Light Aircraft.

We see, then, that the lateral and directional stability characteristics of an aircraft are inextricably linked to each other.

Light aircraft, generally, posses strong directional stability, while having a degree of lateral stability that is not much greater than neutral. Paradoxically, therefore, being much more stable directionally than laterally, a light aircraft will have a marked tendency to yaw into the sideslip, causing further roll, but have a less marked tendency to correct the roll. This sequence of events will, as we have seen, lead to a spiral dive if the pilot does not intervene. Thus, high directional stability and weak lateral stability lead to spiral divergence.

However, if lateral stability were to be high compared to directional stability, the aircraft would display a strong tendency to right itself following a disturbance in the rolling plane, while not showing any strong tendency to turn into the direction of any sideslip. Such an aircraft may even tend to yaw away from the roll. An aircraft with these stability characteristics, therefore, may be prone to an oscillatory motion in both the rolling and yawing planes, known as dutch roll.

As you have learnt, the stability characteristics of light aircraft are such that dutch roll is not a marked feature.

An initial yaw will be followed by roll in the same direction as yaw.

A light aircraft is usually more stable directionally than laterally.

245

Order: 6026

Customer: Oleg Ostapenko E-mail: ostapenko2002@yahoo.com

Customer: Oleg Ostapenko E-mail: ostapenko2002@yahoo.com

CHAPTER 11: STABILITY QUESTIONS

Representative PPL - type questions to test your theoretical knowledge of Stability.

1.With a forward Centre of Gravity, an aircraft will have:

a.reduced longitudinal stability

b.lighter forces for control movements

c.decreased elevator effectiveness when faring

d.shorter take off distances

2.An aft Centre of Gravity will give:

a.increased longitudinal stability

b.heavy forces for control movements

c.increased elevator effectiveness when faring

d.longer take off distances

3.An aircraft is disturbed from its fight path by a gust of wind. If, over a short period of time, it tends to return to its original attitude without pilot intervention, the aircraft is said to possess:

a.instability

b.negative dynamic stability

c.neutral dynamic stability

d.positive dynamic stability

4.An aircraft is disturbed from its fight path by a gust of wind. The aircraft is neutrally stable if, with no intervention from the pilot, it tends to:

a.return to its original attitude without further deviation from its original attitude

b.return to its original attitude following further deviation from its original attitude

c.maintain the new attitude

d.continue to deviate from its original attitude

5.Complete the following sentence in order to give the most satisfactory defnition of stability. An aeroplane which is inherently stable will:

a.require less effort to control

b.be diffcult to stall

c.not spin

d.have a built-in tendency to return to its original state following the removal of any disturbing force

6.After a disturbance in pitch, an aircraft oscillates in pitch with increasing amplitude. It is:

a.statically and dynamically unstable

b.statically stable but dynamically unstable

c.statically unstable but dynamically stable

d.statically and dynamically stable

246