Федеральное агентство по образованию

Государственное образовательное учреждение высшего

профессионального образования

"МОСКОВСКИЙ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЙ ЛИНГВИСТИЧЕСКИЙ

УНИВЕРСИТЕТ"

Т.Б. Межова

«Деликт и гражданская ответственность в Англии и США»

Автор:_________ Межова Т.Б.

Москва 2009

Introduction

I. The word ‘tort’ derives from the Latin tortus, meaning crooked or twisted, and the Norman-French tort, meaning wrong. In English law we use the word tort to denote certain civil wrongs as distinct from criminal wrongs.

A tort is a civil wrong, other than a breach of trust or breach of contract. The law of tort, therefore, provides remedies for the: 1) intentional and direct interference with another's person, property or land (trespass); 2) indirect interference with another's land (nuisance); 3) unintentional and careless interference with another's person or property (negligence); 4) slighting of another's reputation (defamation). It also protects more specialized interests (e.g. business and economic interests), and has specific rules regarding liability for premises and animals. Prior to examining some of these torts in more detail, it is useful to contrast tortuous, criminal and contractual liability:

|

|

Criminal |

Contract |

Tort |

|

Nature of obligations |

Mandatory |

voluntary |

mandatory |

|

Responsibility for enforcement |

State |

individual |

individual |

Thus, criminal law consists of general (or public) obligations, binding on all citizens, enforced by the State. In contrast, contract law consists of private obligations, voluntarily entered into, enforced by the individuals concerned. The law of tort is curious hybrid, consisting of general (or public obligations), binding on all citizens, but that are left for individuals to enforce. First, we must examine the distinctions between (a) a tort and a crime, (b) a tort and a breach of contract, and (c) a tort and a breach of trust. The object of criminal proceedings is primarily punishment. The police are the principal agents to enforce the criminal law, though a private person may also prosecute a criminal offence. If the defendant is found guilty the court may award the proper punishment. The object of proceedings in tort is not punishment, but compensation or reparation to the claimant, previously designated as the plaintiff for the loss or injury caused by the defendant, i.e. damages. The same facts may disclose a crime and a tort. Thus, if A steals B’s coat, there is (i) a crime of theft, and (ii) trespass to goods (a tort) and conversion (also a tort). If X assaults Y, there is both a crime and a tort. In contract the duties are fixed by the parties themselves. They impose terms and conditions themselves by their agreement. In tort, on the other hand, the duties are fixed by law (common law or statute) and arise by the operation of the law itself. Here, too, the same circumstances may give rise to a breach of contract and a tort. Thus, if A hires a taxi-cab driven by B, and B by dangerous driving injures the passenger, (A), the latter will have a cause of action for (i) breach of the contractual duty of care, and (ii) the tort of negligence. So, too, where A employs privately a surgeon, B, to operate on A’s son, B owes A a contractual duty of care. If B fails in that duty there will also be liability in tort to the child.

II. Prof. P.H. Winfield, an important authority in this field, asserts that ‘tortious liability arises from the breach of a duty primarily fixed by law; such duty is towards persons generally, and its breach is redressible by an action for unliquidated damages’

As a general rule, where one person suffers unlawful harm or damage at the hands of another, an action in tort for that damage or injury arises. Sometimes we find instances where harm is done by one person to another yet the law does not provide a remedy: this is described as damnum sine injuria (‘damage without legal wrong’). Ordinary trade competition is the most common example. In contrast to the above, we can imagine a situation where there is a legal wrong but no loss or damage. This is described as injuria sine damno, and is an exception to the general rule that there must be damage or injury before action may be brought. Certain torts are actionable per se (i.e. actionable in themselves). Examples are trespass and libel: in either of these cases no loss need be alleged or proved. In torts not actionable per se, the claimant will succeed only if it can be proved that the defendant has infringed a legal right and that thereby the claimant has suffered damage.

In tort, the intention or motive for an action is generally irrelevant. Malice in the sense of improper motive is, however, relevant to the following cases:

(a) Malicious prosecution. For example, A prosecutes B without just cause; B is acquitted. If it can be proved that A brought the prosecution out of private spite, B may sue A for the offence of malicious prosecution.

(b) Malicious falsehood. For example, A makes an allegation that a ship is unseaworthy; as a result the crew refuses to sail, thereby causing loss. If the allegation is proved to be untrue, A may be sued for the offence of malicious falsehood.

(c) Defamation. The presence of malice will destroy the defence of ‘qualified privilege’ in a case of defamation, and is relevant also to the defence of ‘fair comment’ in libel

(d) Conspiracy, i.e. a combination of persons to cause illegal harm to another. Malice is relevant here in the sense of improper motive.

(e) Nuisance, see Christie v. Davey (1893)

II. The general rule is that anyone of full age may sue and be sued in tort. At common law the maxim ‘The King can do no wrong’ applied until 1947. The Crown Proceedings Act, 1947, altered the common law, and section 2(1) now provides that ‘the Crown shall be subject to all those liabilities in tort to which, if it were a person of full age and capacity, it would be subject.

The Crown is not liable for torts committed by the police by other public officers who are appointed and paid by local authorities, or by members of public corporations such as the Coal Board, Gas Board, and Electricity Board.

Judges have absolute immunity for acts within their judicial capacity. This immunity probably also applies to justices of the peace acting within their jurisdiction. Counsel and witnesses have similar immunity in respect of all matters relating to the case with which they are concerned. A foreign sovereign is not liable in tort in the English courts of law unless they submit to the jurisdiction, thereby waiving their immunity from legal process. They may however, sue in an English court. Ambassadors, High Commissioners and certain other diplomats cannot be sued in tort during their terms of office. A corporation can sue and be sued in its corporate name. It is liable vicariously (i.e. on their behalf) for torts committed by its servants or agents acting within the scope of their authority. These unincorporated bodies enjoy special protection in tort; in certain cases in accordance with the Trade Union Act, 1984, to ensure immunity a ballot must be held prior to a strike. Trades unions may, however, sue in tort in their registered names. As a general rule minority is no defence in tort. Where, however, a tort is founded on malice or where negligence is a necessary ingredient of the tort, the age of the minor is relevant; through want of age a minor may be incapable of forming the specific intent, and what may be negligent in an adult may not be so in respect of a child. If an unborn child is injured by a tort it may sue provided it is born alive and disabled (Congenital Disabilities (Civil Liability) Act, 1976). Where the act complained of is also a breach of contract the claimant cannot avoid the defence of minority by framing his or her action in tort. Parents are not liable, merely because they are parents, for the torts of their children. But a parent will be liable where there has been authorization or commissioning or ordering of a tort, in which case the parent incurs vicarious liability. Secondly a parent may also be held liable for personal negligence where the child has been given the opportunity to do harm. Persons of unsound mind are, in general, liable for their torts. However, a person of unsound mind who is incapable of forming the intention or malice as required in torts of malicious prosecution or deceit, will not be held liable. Similarly, a person who is so insane that their actions are involuntary, will escape liability. The wife may now sue and be sued in tort as a feme sole (i.e. as a single woman), and the husband is no longer liable for his wife’s torts by reason only of being her husband. Where, however, the wife is agent or servant of her husband he may render himself vicariously liable (Law Reform (Married Women and Tortfeasors) Aliens fall into two classes: enemy aliens and other aliens. Enemy aliens are members of a state with which England is at war, or persons (including British subjects) who ‘voluntarily reside or carry on business’ in that state. Such persons cannot bring an action in tort, but they may if sued defend one, and they may appeal. Other aliens have neither disability nor immunity.

CHAPTER ONE

NEGLIGENCE

UNIT ONE

1. Read the following text

What is Negligence

Negligence is the failure to take reasonable care where a duty to do so exists, and where that failure causes recoverable loss or damage to the person to whom the duty is owed. Therefore, negligence is more precise than simple carelessness, and is only actionable upon proof of damage. Negligence emerged as a distinct tort from the tort of trespass. Its separate existence was established conclusively by the House of Lords in Donoghue v. Stevenson |1932]. Here, for the first time, the House of Lords sought to identify the general principles underlying negligence, and Lord Atkin advanced his famous neighbor principle:

1) you are under a duty to take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions that you can reasonably foresee might injure your neighbor;

2) your neighbor is someone so closely and directly affected by your actions that you ought reasonably to have them in mind as being so affected when considering those actions;

These notions of a duty of care and neighborhood remain the central foundations of the modern tort of negligence. Following various refinements and variations since 1932, five requirements must be met for negligence liability to arise:

1) the damage suffered by the claimant must disclose a cause of action;

2) the defendant must owe the claimant a duty of care;

3) the defendant must have been in breach of that duty;

4) the breach of duty must have been a cause in fact of the claimant's damage;

5) the claimant's damage must have been a reasonably foreseeable consequence of the defendant's breach.

The cause of action

The forms of damage that are recoverable in negligence are:

1) personal injury;

2) physical damage to property;

3) economic loss consequential on either of the above.

However, pure economic loss is generally not recoverable (Spartan Steel & Alloys Ltd v. Martin & Co (Contractors) Ltd [1973]; D & F Estates Ltd v. Church Commissioners [1989]; Murphy v. Brentwood D.C. [1990]). This limitation is not a matter of principle (as pure economic loss is often reasonably foreseeable). Rather, it is a matter of policy to avoid placing the defendant in a position of almost unlimited liability.

There is one important exception to this general position. Pure economic loss is recoverable where there is a special relationship between claimant and defendant, i.e. where the claimant was relying on the specialist skill and knowledge of the defendant (Hedley Byrne & Co Ltd v. Heller & Partners Ltd [1964]; Junior Books Ltd v. Veitchi Co Ltd [1982]; Simaan General Contracting Co v. Pilkington Glass Ltd (No. 2) [1988]).

The duty of care

As noted above, Lord Atkin's original formulation of neighborhood as the test for duty of care has been subject to a number of refinements (e.g. in Anns v. Merlon L.B.C. [1978]; Yuen Кип Yeu v. Attorney General of Hong Kong [1988])

The present test is one of proximity, i.e. there must be a sufficiently proximate (or close) relationship between claimant and defendant so that it is fair, just and reasonable in the circumstances to impose a duty of care on the defendant (Caparo Industries plc v. Dickman [1990]; Davis v. Radcliffe [1990]). For proximity to arise there must be neighborhood (in the sense of foreseeability of harm). However, neighborhood alone does not automatically amount to proximity. The court also considers previous cases by way of analogy and, where appropriate, questions of public policy (e.g. Hill v. One Constable of West Yorkshire [1988]). Therefore, proximity is a more flexible (and less predictable) notion than that of neighbourhood. There are two particular situations where the courts have imposed additional requirements (over and above mere neighborhood) in order to satisfy the requirement of proximity and, hence, to give rise to a duty of care.

Negligent statements

In Hedley Byrne & Co Ltd v. Heller & Partners Ltd [1964], the House of Lords held that liability for negligent statements must be treated differently (and in a more restricted way) to liability for negligent acts because:

1) reasonably careful people tend to be more careful over what they do than what they say;

2) while negligent acts tend to have a limited range of effect (giving rise to a limited amount of liability), negligent words can have a much wider effect (e.g. where they are broadcast) and could give rise to excessive and almost unlimited liability;

3) negligent words generally cause only pure economic loss which again, as noted above, could involve the defendant in excessive liability.

Therefore, rather than a mere relationship of neighborhood, a special relationship is required to give rise to the necessary proximity in such cases. According to Caparo Industries plc v. Dickman [1990], a special relationship arises where:

1) the person seeking the information or advice was relying on the other to exercise care and skill in their reply;

2) this reliance was reasonable in the circumstances;

3) the maker of the statement knew that his statement would be communicated to the inquirer (either as an individual or member of an identifiable class) specifically in connection with a particular transaction or transactions of a particular kind;

4) the maker of the statement knew that the inquirer would be very likely to rely on it for the purpose of deciding whether or not to enter into that transaction or transactions of that kind.

There is no requirement that the maker of the statement be in the business of giving information or advice of the type sought. It is sufficient that he holds himself out as possessing the required skill or knowledge and the inquirer reasonably relies on this (Chaudhry v. Prabhakar [1988]).

2. Answer the following questions

1. What is negligence?

2. When is negligence actionable?

3. What does Lord Atkin’s famous principle consist of?

4. What five requirements must be met for negligence liability to arise?

5. What are the forms of damage that are recoverable in negligence?

6. Why is pure economic loss generally not recoverable?

7. What is the present test for the duty of care?

8. What is the meaning of ‘proximity’ and ‘neighborhood’?

9. What special relations can give rise to the proximity?

10. What conditions should be met to impose the liability on the maker of the statement?

3. Find the English for

1) обязанность соблюдать разумную предосторожность, 2) повод для судебного разбирательства при наличии доказательств причинения ущерба, 3) знаменитый принцип соседства, 4) избегать действия или бездействия, влекущего нарушение этой обязанности, 5) причинная связь, 6) неподлежащие компенсации финансовые потери, 7) привести к практически неограниченной ответственности, 8) полагаться на специальные (профессиональные) навыки и знания, 9) тест о соблюдении должной степени предосторожности при наличии пространственной близости, 10) правильно, справедливо и разумно, 11) служить основанием для возникновения ограниченной ответственности, 12) полагаться на другое лицо для соблюдении должной степени осторожности и мастерства, 13) предоставлять необходимую профессионально-компетентную информацию или совет, 14) выдавать себя за лицо, обладающее профессиональными квалификациями

3. Supply the right articles where necessary to complete the sentences and answer the question: “What policy considerations’ determine the duty of care?”

(…) policy plays a vital role in determining (…) existence of (…) duty of care. It can be defined as (…) departure from established legal principle for (…) pragmatic purposes. There are some issues of policy that are commonly raised: 1) To allow (…) claim would open (…) ‘floodgates’ and expose (…) defendant to (…) indeterminate liability. 2) The imposition of (…) duty would prevent (…) defendant from doing his job properly. This leads to (…) class of ‘protected parties’ (… ) persons who enjoy immunity from (…) suit: (…) judges and (…) witnesses in judicial proceedings enjoy immunity on (…) grounds of ‘public policy’; as well as barristers and solicitor-advocates. Lawyers used to enjoy immunity concerning their conduct of cases in (…) court. There is also ‘public policy’ immunity for ( ) carrying out of public duties by (…) public bodies.

The European Court of Human Rights deprecated (…) idea of blanket immunity for (…) police from negligence actions in 1998 - especially when police actions led to (…) fatality. However (…) police may be liable where there is (…) special relationship between (…) police and (…) informant. (…) same immunity for (…) discharge of public duties , unless responsibility had exceptionally been assumed to (…) particular defendant, also applies to (…) Crown Prosecution Service, (…) fire brigade (…) ambulance service

4. Supply the right tense and aspect form of the verb to complete the sentences and answer the question “When is liability for physical injury and physical loss imposed?”

Particular aspect of a duty of care and physical injury The meaning of the term ‘proximity (vary) varies according to who (use) the term, when it (use) and the type of injury that (be) suffered. As far as physical injury (be) concerned the courts readily (hold) the parties to be proximate and, for this type of injury, proximity really (equate) to foreseeability. However the House of Lords (hold) in Marc Rich & Co AG v Bishop Rock Marine Co Ltd (1995) that even in cases of physical damage, the court (have) to consider not only foreseeability and proximity but also whether it (be) fair, just and reasonable to impose a duty. Speaking about physical loss, the law (will) more readily impose liability for directly inflicted physical loss than for indirectly inflicted.

5. Supply the right English word to make sentences complete

|

1) rely on him, 2) foreseeable, 3) oblige, 4) favorably disposed, 5) negligent |

Rescuers The law does not oblige a person to undertake a rescue unless the parties are in special relationship, but the courts are favorably disposed to someone who does attempt a rescue and is injured in the process. Rescuers may be owed a duty in situations when 1) rescue is foreseeable. (Haynes v Harford (1935)) and 2) there must be real threat (Cutler v United Dairies (1933)). But rescuer himself can owe a duty to the accident victim when 1) the rescuer is negligent (Horsley v MacLaren (1979)) and 2) if he induced the claimant rely on him. (Zelenko v Gimbel Bros (1935)).

CASES

Analyze the following cases and advise your client on the existence of the duty of care. (If necessary find more information about these cases in the world internet.)

1) The plaintiff was a soldier serving with the British Army in the Gulf War. He was injured and his hearing was affected when his gun commander negligently ordered a gun to be fired. (Mulcahy v Ministry of Defence (1996)).

2) The plaintiff who was a trespasser and engaged in criminal activities was attempting to break into a brick shed on the defendant’s allotment. The defendant poked a shot gun through a small hole in the door and fired, injuring the plaintiff. (Revill v Newberry(1995)).

3) One of the defendants unsuccessfully inspected a light aircraft and certified that it was airworthy. The other defendant was certifying authority. The plaintiff was the passenger injured in a test flight. (Perrett v Collins (1995)).

REVISION AND PRACTICE SECTION

1. You should now write your revision notes for Nuisance. Give your definition to

1. Cause of action, 2. Duty of care

UNIT TWO

1. Read the following text

Nervous shock

Nervous shock is a precise term meaning a recognized psychiatric illness (e.g. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) caused by shock. The law does not recognize claims for ordinary grief or sorrow, no matter how keenly or deeply felt. As with negligent statements, it is the potential breadth of liability that is the prompt for limitations here. As Lord Wilberforce observed in McLaughlin v. O'Brian [1982], "just because 'shock' in its nature is capable of affecting so wide a range of people there is a very real need for the law to place some limitation on the extent of admissible claims". Therefore, it would seem that a person is owed a duty of care in respect of nervous shock where:

1) the shock is consequent upon physical injury to himself; or

2) the shock is consequent upon a reasonably apprehended fear of physical injury to himself, even though no injury in fact occurs (Dulieu v. White [1901]); and

3) personal injury to the claimant (whether physical or psychological) is reasonably foreseeable (Page v. Smith [1995]).

The position is a little more complicated where shock is caused by injury or fear of injury to another person. The House of Lords stated the present position here when considering a series of test cases arising from the Hillsborough Stadium disaster (Alcock v. Chief Constable of South Yorkshire Police [1991])—a person is owed a duty of care in respect of nervous shock where:

1) the shock is consequent upon physical injury to another; and:

2) the claimant sees or hears (or some equivalent thereof) the accident itself or its immediate aftermath; and

3) the claimant (the secondary victim) has a close relationship of love and affection with the injured person (the primary victim) (McFarlane v. E E Caledonia Ltd [1993]) or the claimant is a rescuer (Chadwick v. British Transport Commission [1967]); and

4) psychological injury to the claimant (the secondary victim) is reasonably foreseeable (Page v. Smith (1995]); or 5) the shock is consequent upon a reasonably apprehended fear of physical injury to another, even though no injury in fact occurs, and the requirements stated above are met.

The "immediate aftermath" of the accident extends to the hospital to which the injured person is taken and persists for as long as that person remains in the state produced by the accident, up to and including immediate post-accident treatment (McLoughlin v. O'Brian [1982]).

The breach of duty

The defendant will be in breach of his duty of care if he fails to show reasonable care. This is essentially an objective test, measuring the defendant's conduct against the degree of care a reasonable man would have exercised in the same circumstances.

The reasonable man

The reasonable man is expected to possess a certain amount of basic knowledge (e.g. that acid burns) and to show a basic or ordinary level of skill. Generally, expert skill or knowledge is not expected unless the defendant has claimed such knowledge or skill (Phillips v. William Whitely Ltd |1938|). Even where expert skill or knowledge is required, the standard expected remains that of the reasonably competent expert in the given field. It may be evidence of the fact that the defendant has acted reasonably to show he acted in accordance with general, accepted or approved practice in the given field. This comparison, must be with the accepted practice at the material time, discounting any subsequent developments, alterations or advances (Roe v. Minister of Health [1954]). However, this comparison will not help the defendant where it would have been clear to a reasonable man that the accepted practice was itself negligent (Cavanagh v. Ulster Weaving Ca Ltd [1960],

An exclusively objective test would, in some circumstances, lead to injustice. Therefore, there are circumstances where the court will modify the objective standard by taking into account certain subjective characteristics of the defendant:

1) Mental or physical incapacity may make it impossible for the defendant to show reasonable care. It would be unjust to hold them negligent in failing to show, the degree of care it is impossible for them to achieve. However, a person may be negligent in placing himself in a position that requires a degree of care he knows he is unable to achieve.

2) Young children are not required to show the same degree of care as adults. An allowance is made as their youth and immaturity may prevent them appreciating fully the risks and consequences of their actions (Cough v. Thorne [1966]).

3) The elderly are not expected to show the same degree of physical or mental agility or speed of reflex as that of a younger adult (Daly v. Liverpool Corporation [1939]). The allowance made here is less than that for children, as the elderly have the benefit of knowledge and experience that the child does not. The law also requires people to take account of the effects of ageing and a failure to do so may itself amount to negligence.

4) The court may take account of illness on the part of the defendant provided it is both sudden and incapacitating and there has been no forewarning (Ryan v. Youngs [1938]).

Reasonable care

In deciding what amounts to reasonable care in the circumstances, the courts will consider two main factors. The first one is the degree of risk created by the defendant's conduct. (This may be so slight that the reasonable man would be entitled to ignore it (Bolton v. Stone [1951]). Therefore the general approach is that the greater the degree of risk created, the greater the degree of care that should be taken to guard against it.) The second factor is the seriousness of the potential harm. Again, the greater the potential harm is, the greater the obligation to take care to prevent it should be (Paris v. Stepney B.C. |l95l]). The court may also take consider the social utility of the defendant's activities and the cost and practicability of taking precautions against the risk.

2. Answer the following questions

1. What does nervous shock mean in legal terminology?

2. When is a duty of care owed to a person?

3. What conditions must be satisfied in order to impose a duty of care as to nervous shock?

5. What is the importance of personal injury factor in case of nervous shock?

6. Can a rescuer undergo a nervous shock?

7. What is considered the immediate aftermath of the accident?

8. What is an objective test for the breach of duty of care?

9. What is the general definition of a reasonable man?

10. What factors are relevant in respect to reasonable power?

3. Find the English for

1) психическое заболевание, 2) обычное горе или печаль, 3) ответственность перед широким кругом лиц, 4) иски к рассмотрению, 5) шок как прямое следствие, 6) разумно обоснованный страх получения телесных повреждений, 6) оказание неотложной медицинской помощи, 7) не проявлять разумную осторожность, 8) определенный объем базовых знаний и обычный уровень навыков, 9) соответствовать общепринятой и признанной в данной области практике, 10) умственная или физическая ограниченная способность, 11) проявлять должную степень предосторожности, свойственную взрослому человеку, 12) при внезапном наступлении болезни

4. Supply the right prepositions where necessary and answer the question: “Who are in law primary victims?”

Primary victims The law (…) negligence relating (…) nervous shock makes an important distinction (…) primary and secondary victims. Primary victims are those who have been directly involved (…) the accident and are (…) the range (…) foreseeable injury. There are no policy control mechanisms to limit the number (…) claimants. The question (…) foreseeability is the basic one and there is no distinction (…) physical and psychiatric injury while ruling (…) claims (…) nervous shock. Primary victims are those who fear physical injury (…) themselves, or rescuers (…) the injured, or those who believe they are about to be, or have been, the involuntary cause (…) another’s death or injury.

5. Supply the words from the table to make the sentences complete. Answer the question: What criteria must be satisfied to recover as a secondary victim?”

|

1. liability 2. distress or grief 3. claim 4. recover 5. in a close and loving relationship 6. in the vicinity of 7. with his own unaided senses |

Secondary victims Before there can be (нести ответственность) in the case of secondary victims, there must be a medically recognized psychiatric illness or medical disorder; there is no liability for emotional (расстройство или горе) unless this leads to a recognizable medical condition. There have been held to include: depression, personality charge, post-traumatic stress disorder. It was held that there could be no (иск) for the terror suffered immediately before death for the knowledge that the death was imminent. An abnormally sensitive claimant will be unable to recover unless a person of ‘normal fortitude’ would have suffered There are some other criteria that the claimant will have to satisfy before they can (получать компенсацию) for nervous shock in the case of secondary victims.

Proximity in terms of relationship- the claimant must be (быть в близких отношениях и любить) with the accident victim. Rescuers are the exception to the case.

Proximity in terms of time and space- the claimant must be at the scene of the accident, (в непосредственной близости от) the accident or come across the ‘immediate aftermath’ of the accident. The claimant’s injuries must be reasonably foreseeable. There must be a direct perception of the accident by the claimant (без посторонней помощи).

CASES

1. Advise your client on his/her liability to primary victims resulting from nervous shock:

1) The plaintiff suffered from chronic fatigue syndrome, or post-viral fatigue syndrome. The plaintiff was physically uninjured in a collision between his car and a car driven by the defendant but his condition became chronic as a result of the accident. (Page v Smith (1995))

2) Police Officers Suffered nervous shock while on duty, in rescuing the victims of a disaster caused by negligence for which their employer was responsible. (Frost v Chief Constable of South Yorkshire (1999))

3) A social worker suffered a nervous breakdown when chronically overworked by his employer (Walker v Northumberland County Council (1995))

2. Advise your client on his/her liability to secondary victims resulting from nervous shock:

1) The plaintiff was two miles from the accident but rushed to the hospital to see her family prior to them receive medical treatment. He claimed recovery for nervous shock. (McLoughlin v O’Brian (1983))

3. Advise your client on his/her recovery for economic loss.

a) The plaintiffs had suffered loss because their lobsters had been killed as a result of defective motors on the tank. They claimed to recover the cost of lobsters and repairs of the tank and also the loss of profit (Muirhead v Industrial Tank Specialties Ltd (1986))

b). The plaintiffs were shareholders in a company and, as such, were entitled to annual auditing accounts. On the basis of these accounts, they launched a takeover bid in the company before discovering that the accounts had been negligently audited and ha d wrongly shown the company to be profit-making.( Caparo Industries plc v Dickman (1990))

REVISION AND PRACTICE SECTION

1 You should now write your revision notes for Nuisance. Give your definition to

1. Nervous shock. 2. Primary victims 3. Secondary victims

2 Using your cards, you should now be able to write a short paragraph in response to the following question:

1. When in law a person is owed a duty of care in case of nervous shock?

UNIT THREE

1. Read the following text

Proof of breach

The burden of proving breach lies on the claimant. This is the civil burden of showing that, on the balance of probabilities; the defendant was in breach of duty. However, for a variety of practical reasons, it may be extremely difficult (or even impossible) for the claimant to present definite proof of the defendant's breach. In such circumstances, the claimant may be able to rely on the res ipsa loquitor maxim. This is a rule of evidence that asks the court to accept that "the facts speak for themselves" and infer breach of duty from the general circumstances of the case. For the maxim to apply, two requirements must be met (Scott v. London & St Katherine Docks Co |1863]):

1) the accident must be of a type that does not normally occur without someone having been negligent;

2) the circumstances must not merely indicate negligence by someone but negligence on the part of the defendant.

The maxim can only be used to establish breach of duty. It cannot be relied on to establish the required causal link between the defendant's breach and claimant's damage.

The causal link

For the defendant to be liable there must be a clear, unbroken causal link between his breach of duty and the damage suffered by the claimant, i.e. the breach must be a cause in fact of the damage. This is established by the application of the but for test, i.e. but for the defendant's breach of duty, would the damage to the claimant have occurred? Where, on the balance of probabilities, the damage would not have occurred, the defendant will be held responsible. Where, by contrast, the damage would probably have occurred in any event, the defendant will not be liable (Barnett v. Chelsea & Kensington Hospital Management Committee [1969]; Hotson v. East Berkshire Health Authority [1987]; Wilsher v. Essex Area Health Authority [1988]).The defendant's breach need not be the sole cause of the damage. It is sufficient that it makes a significant material contribution (Bonningtons Castings Ltd v. Wardlaw [1956]). However, it must have been a cause—merely increasing the risk of damage is not sufficient (Wilsher v. Essex Area Health Authority [1988]; Page v. Smith (No. 2) [1996]).

Foreseeability of harm and remoteness of damage

In addition to establishing a factual causal link, the .claimant must also establish that the breach was a cause in law of the damage. Following the decision of the Privy Council in The Wagon Mound (No. 1) [1961], the defendant will only be liable for damage that is a reasonably foreseeable consequence of his breach. Damage which is not reasonably foreseeable is regarded as too remote from the breach and, therefore, not recoverable. In establishing that damage was reasonably foreseeable, the claimant does not have to show the precise nature, extent or manner of occurrence was foreseeable (Stewart v. West African Air Terminals Ltd [1964]). What must be established is that the damage suffered was a reasonably foreseeable type of damage, occurring in a reasonably foreseeable manner. For example, in Hughes v. Lord Advocate [1963], burns sustained in a gas explosion (which was itself unforeseeable) were held to be within the general range of injuries which might reasonably foreseeabiy arise from leaving a paraffin lamp unattended at road works. In Bradford, v. Robinson Rentals Ltd [1967], frostbite (though itself unforeseeable) was held to be within the general range of reasonably foreseeable injuries resulting from exposure to cold. However, in Doughty v. Turner Manufacturing Co Ltd [1964], injuries sustained when an asbestos cover fell into a vat of chemicals, causing them to erupt, were held to be outside the general range of reasonably foreseeable injuries that might result from being splashed by chemicals. While splashing was reasonably foreseeable, the chemical eruption was not. Therefore, it is sometimes difficult to predict when the courts will regard unusual injuries or manners of occurrence as being unforeseeable or as being merely an unusual variation of reasonably, foreseeable consequences (Jolley (A.P.) v. Sutton L.B.C. [2000]).

There is no requirement that the extent of the damage be reasonably foreseeable (Vacwell Engineering Co Ltd v. BDH Chemicals Ltd [1971]). This principle stands alongside the thin skull rule, which requires the defendant take his victim as he finds him. Therefore, the defendant cannot argue he is not responsible for damage aggravated by the physical (Dulieu v. White [1901]) or mental (Brice v. Brown [1984]) peculiarities of the claimant. That this rule survives the decision in The Wagon Mound is clear from Smith v. Leech Brain & Co Ltd [1962], where latent cancer was triggered into activity by a burn.

Defences to negligence

Where the claimant has met these five requirements, the defendant will be liable unless he is able to raise a defence. There are three main possibilities: Contributory negligence, volenti non fit injuria, exclusion of liability.

2. Answer the following questions

1. Who bears the burden of proving the breach of duty?

2. Why is the maxim res ipsa loquitor applied in difficult cases?

3. What factors should be considered to find the defendant liable?

4. What does the test ‘but for’ consist of?

5. What is the interrelation between the breach of duty and the damage caused?

6. How can the claimant prove that the damage was foreseeable?

7. What is the example to illustrate this principle?

8. What is the ‘thin skull rule’ principle?

3. Find the English for

1) вещь говорящая сама за себя (лат) 2) бремя гражданского судопроизводства 3) исходя из степени наибольшей вероятности 4) установленная причина 5) причинно следственная связь между нарушением обязанности и причиненным истцу ущербом 6) считать слишком удаленным 7) одна из обычных причин причинения вреда здоровью 8) сущность, размеры или способ каким был причинен вред здоровью можно было предвидеть 9) оставлять без присмотра (вещь) 10) умереть от переохлаждения организма 11) правило «хрупкого черепа» 12) рассматривать пострадавшего исходя из объективных особенностей личности 13) физические или умственные особенности

4. Read the extract and explain the use of tenses in the following cases. Answer the question: “Why was there a difference in decisions if the facts of the two cases are almost the same?”

A) A cricket ball had been hit out of a cricket ground six times in 28 years into a nearby, rarely used lane . On the seventh occasion, it hit a passer-by in the lane. Held: the chances of such an accident were so small that it was not reasonable to expect the defendant to take precautions against it happening. (Bolton v Stone (1951)) B) A cricket ball was hit out of the ground eight to nine times a season. Held: the defendant had been negligent as it was reasonable to expect the defendant to take precautions. (Miller v Jackson (1977))

5. Supply the linking words and conjunctions from the table to complete the sentences and answer the questions 1) “When shall the plaintiff recover for negligence?

|

as where which that that |

The law of negligence does not give the same level of protection to economic interests (1…) it does to physical interests. There are only three types of situation (2…) recovery is allowed in negligence for economic loss: a) economic loss (3…) is consequential upon physical damage; b) negligent statements; c) ‘pockets of liability’ (4…) which are thought to survive (see Murphy v Brentwood DC (1991)). Economic loss It is long established (5…)economic loss as a result of physical injury is recoverable not only for the cost of repairing physical damage to person or property but also for ‘consequential’ loss of earnings or profits during convalescence or repair. Negligent misstatements The difficulty in negligent misstatements (6…) caused economic loss is that they may be made on an informal occasion and passed on without the consent of the speaker.

6. Read the text and answer the question: “What is contributory negligence defence?”

Contributory negligence This is where the claimant's damage is due, in part, to his own negligence. Under the Law Reform (Contributory Negligence) Act 1945, this is a partial defense, allowing the court to apportion responsibility for the damage between the claimant and defendant and reduce the defendant's liability accordingly. The defendant must show:

1) the claimant failed to exercise reasonable care for his own safety (Davies v. Swan Motor Co (Swansea) Ltd [1949]);

2) This failure made a material contribution to the claimant's damage {Jones v. Livox Quarries Ltd (1952)). In apportioning responsibility, the court considers two factors:

3) the extent to which the actions of the claimant and defendant were a cause of the damage (the causative potency test);

4) the degree to which the claimant and defendant departed from the standards of the reasonable man (the degree of blameworthiness test).

For example, failure to wear a seat belt will generally result in a reduction of 25 per cent where wearing the belt would have eliminated the injury completely, and 15 per cent where the injury would have been less severe (Froom v. Butcher [1976]). As with the position of the defendant in general negligence, the court may modify the test of reasonableness by taking into account certain subjective characteristics of the claimant.

Regarding contributory negligence, in addition to the factors of mental or physical incapacity, youth or old age, the court may also take into account: 1) where contributory negligence is alleged against a worker, consideration may be given to the fact that the worker's appreciation of risk may have lessened through familiarity with the work or the noise and stress of the workplace (Grant v. Sun Shipping Co Ltd (1948)); 2) where the claimant has been placed in a position of danger by the defendant's negligence and, in the agony of the moment, seeks to escape this danger, he will not be contributory negligent should this decision turn out to be mistaken (Jones v. Boyce(1816)), provided his apprehension of danger is reasonable. This remains so even where the claimant has time to reflect upon his situation (Haynes v. Harwood (1935)). However, while the claimant may not be contributory negligent in his decision to attempt escape, he may be negligent in his choice of method or its operation {Sayers v. Harlow U.D.C.(1958)).

7) Read the text and answer the question: “What is volenti поп fit injuria defence?”

Volenti поп fit injuria Volenti (consent to the risk) is a complete defence to negligence. However, the circumstances in which it may be raised are severely limited and it is of little practical application today. This is partly because the courts prefer to find a claimant contributory negligent (allowing them to apportion responsibility) rather than as being volens to the risk, e.g. a claimant who accepts a lift from a driver he knows has been drinking will generally be regarded as contributory negligent (Owens v. Brimmell [1977]). However, volenti may apply where the claimant is aware that the driver is so drunk that an accident is a virtual certainty (Ashton v. Turner [1981]; Morris v. Murray (1990)). Furthermore, the effectiveness of consent to express exclusions of liability has been significantly restricted by the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 (see below). Volenti may be inferred from the claimant's conduct where four requirements are met (Id Ltd v. Shatwcl (1965)):

1) the claimant was aware of the defendant's negligent conduct;

2) the claimant was aware of the risk to himself that this created;

3) the claimant continued to participate freely in the activity in the face of this knowledge;

4) the damage suffered was a reasonably foreseeable consequence of the risk consented to.

Regarding the position of rescuers, volenti cannot be raised against a rescuer provided the decision to attempt rescue was a reasonable one (Haynes v. Harwood [1935]; Culler v. United Dairies (London) Ltd [1933]). This remains so even where the rescuer knows there is a virtual certainty of injury. Furthermore, even where the decision to rescue was unreasonable, or where the rescuer has been negligent in his choice of method or its operation, the courts will generally regard this as contributory negligence rather than volenti. This preferential treatment is because the courts do not wish to discourage people from acting as rescuers. They do not make any fundamental distinction here between the layman and professional rescuer (Ogwo v. Taylor [1987]). The fact that a person's employment is inherently dangerous does not make them volens to risks arising from another's negligence. However, the particular skills and knowledge of the professional are relevant in deciding whether they exercised reasonable care for their own safety in assessing contributory negligence.

8) Read the text and answer the question:” What is exclusion of liability defence?”

Exclusion of liability The defendant may seek to rely on ал undertaking by the claimant to accept the risk of negligence in order to exclude or limit his liability. However, as noted above, the extent to which he can do this is limited by the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977: 1) section 2(1) provides that a person cannot, by reference to any contractual term or non-contractual notice, exclude or restrict business liability for causing death or personal injury through negligence; 2) section 2(2) provides that such liability for other forms of loss or damage can only be excluded or restricted in so far as the term or notice is reasonable; 3) section 2(3) provides that a person's agreement to or awareness of such a term or notice does not, in itself, amount to volenti.

Nevertheless, there may still be certain non-business situations where such undertaking would be effective in excluding or restricting the defendant's liability.

CASES

1. Advise your client on his/her liability to primary victims resulting from nervous shock

1) The plaintiff was a soldier serving with the British Army in the Gulf War. He was injured and his hearing was affected when his gun commander negligently ordered a gun to be fired.( Mulcahy v Ministry of Defence (1996))

2) The plaintiff who was a trespasser and engaged in criminal activities was attempting to break into a brick shed on the defendant’s allotment. The defendant poked a shot gun through a small hole in the door and fired, injuring the plaintiff. (Revill v Newberry(1995)).

3) One of the defendants unsuccessfully inspected a light aircraft and certified that it was airworthy. The other defendant was certifying authority. The plaintiff was the passenger injured in a test flight. (Perrett v Collins (1995))

2. Advise your client whether there was a breach of duty in the standard of care. Study the chart below

1) The plaintiff was blind in one eye. While he was working for the defendants, a metal chip entered his good eye and rendered him totally blind. (Paris v Stepney BC (1951))

2) The plaintiff was a fireman and part of a rescue team that was rushing to the scene of an accident to rescue a woman trapped under a car. The plaintiff was injured by a heavy piece of equipment which had not been properly secured on the lorry on which it was traveling in the emergency circumstances (Watt v Hertfordshire CC (1954))

3) The defendant’s factory was flooded; the water mixed with factory oil and made the floor slippery. Sawdust was spread on the surface, but not enough to cover the whole affected area. (Latimer v AEC Ltd (1953))

REVISION AND PRACTICE SECTION

1. You should now write revision notes for negligence. Give the definition to

1) Causation 2) Foreseeability of Damage 3) Defences [volenti] 4) Defences (exclusion of liability) 5) Defences (Contributory Negligence)

2. Explain the rules of law relating to the following area of negligence

1) Breach of Duty as an element in a tort of negligence

CHAPTER TWO

NUISANCE

UNIT ONE

1. Read the following text

Private nuisance

Private nuisance is the indirect and unreasonable interference with the use or enjoyment of neighbouring land (Sedleigh-Denfield v. O'Callaghan (1940)). This may be caused by many different things, e.g. noise, smoke, odours, fumes, water and plant and tree roots. The basis of liability here is the failure to meet the reasonable expectations of one's neighbours. While this has clear similarities with negligence, there are also important differences. In negligence, the question is whether the defendant's conduct was reasonable, while in nuisance the question is whether the effect of that conduct on the defendant's neighbours is reasonable. Therefore, if the defendant's conduct in fact causes an actionable nuisance, it is no defence to show that he has taken reasonable care to prevent this. If the defendant cannot carry on a particular activity without causing an actionable nuisance, then he should not carry on that activity or, at least, should carry it on somewhere else (Rapier v. London Tramways Co [1893]). This means that nuisance can, in certain circumstances, take on the appearance of a tort of strict liability

Proof of damage

This is the essential element. A nuisance is only actionable where it causes damage to the claimant's interests. This requirement is clearly satisfied where the nuisance causes physical damage to the claimant's land, as this is always unreasonable. Where the damage complained of is disturbance to use or enjoyment, this must be more than trivial (Andreae v. Selfridge [1938])—the law expects a degree of give-and-take between neighbours (Bamford v. Turnley [1862]).

Other relevant factors

While proof of damage is essential to a successful nuisance action, there are a number of other factors the court may consider:

1) Generally, the nuisance must be of a continuing or regular nature. Isolated or irregular instances will not normally amount to a nuisance (Bolton v. Stone (1951)). However, where the defendant is responsible for a continuous state of affairs with the potential for nuisance, he may be liable immediately should a nuisance in fact occur (Spicer v. Smee([1946)).

2) Where the damage complained of is disturbance, to use or enjoyment, the court may consider the character of the neighbourhood (St Helen's Smelting Co v. Tipping [1865]). What may be reasonable in an industrial area may not be in a residential area. Similarly, what may reasonable in a busy city may not be in a quiet village.

3) The fact the claimant may be unusually sensitive is not relevant to the issue of liability—the test remains the expectations of the reasonable neighbour (Robinson v. Kilvert [1889]). However, once liability has been established, unusual sensitivity may be relevant to the question of remedies (McKinnon Industries Ltd v.Walker [1951]).

4) While malice on the part of the defendant is not an essential requirement, the presence of malice may tip the balance, converting otherwise reasonable conduct into an actionable nuisance (Christie v. Davey [1893]; Hollywood Silver Fox Farm Ltd v. Emmett [1936]). 5) The defendant may be liable for a nuisance caused by the fault of another or due to natural causes. This is known as "adoption" or "continuance" of nuisance, and arises where the defendant knew or ought to have known of the nuisance and failed to take reasonable steps to stop it (Leakey v. National Trust [1980])

2. Answer the following questions

1) What is private nuisance?

2) What makes a basis of liability for nuisance?

3) What is the difference between a tort of negligence and a tort of nuisance?

4) What is the standard of proof to make a tort of nuisance actionable?

5) Shall every interference with ‘others’ use of land amount to nuisance?

6) What factors are relevant in classifying the deed as nuisance?

7) Why is malice important in determining a tort of nuisance?

3. Find the English for

1) источник опасности или неудобства для какого-л. лица или группы лиц, 2) непрямое и необоснованное вмешательство, 3) не оправдывать разумные ожидания соседей, 4) судебно наказуемое гражданское правонарушение создания помех (неудобства), 5) заниматься какой-либо деятельностью без причинения неудобства другому лицу, 6) наносить вред интересам истца, 7) значительный причиненный вред, 8) компромисс, взаимные уступки, 9) особенности прилегающей местности, 10) злой умысел со стороны ответчика

5. Supply the words from the table to make the sentences complete. Answer the question: “What is the difference between public and private nuisance?”

|

1) confusion, 2) a public and a private, 3) interferences with rights of the public at large, 4) harassing telephone calls at home, 5) suffered particular damage, 6) some right over or in connection with it 7.) land |

There tends to be 1)… between public and private nuisance. Public nuisance is a crime covering a number of 2)…., such as brothel keeping, selling impure food and obstructing public highways. It is not tortious unless an individual proves that he has 3)… beyond that suffered by the rest of the community. Private nuisance is an unlawful interference with the use or enjoyment of land, or 4) …. At one time, the law of private nuisance seemed to be moving away from solely restraining activities which affected enjoyment of 5)…. In Khorasandijan v Bush (1993), the plaintiff was granted an injunction not only in respect of 6)…, but also for harassment at work and in the street. The House of Lords in Hunter v Canary Wharf (1997) rejected this approach and confined nuisance to its traditional … boundaries. Lord Hoffmann emphasized, in that case, that it is a tort relating to land. Public nuisance is different from private nuisance as it is not necessarily connected with the user of land. Public nuisance is usually a crime, although it can be a tort. To make matters even more confusing, the same incident can be both 7)… a public and a private nuisance.

6. Supply the right articles where necessary to make the sentences complete

Private nuisance is … unlawful interference with … use or enjoyment of .. land, or some right over or in connection with it. What is unlawful falls to be decided in an ex post facto manner. Most activities which give rise to ... claims in nuisance are in themselves lawful. It is only when … activity interferes with another's enjoyment of land to such … extent that it is … nuisance that it becomes unlawful Examples of … private nuisance: It was said by Lord Wright that ' .. forms that nuisance take ‘are protean’. Examples would be as follows

1) Encroachment on the claimant's land, Davey v Harrow Corporation (1958).

2) Physical damage to the claimant's land, Sedleigh-Denfield v O'Ca/laghan (1940).

3) Interference with the claimant's use or enjoyment of land through smells, smoke, dust, noise, etc, Halsey v Esso Petroleum Co Ltd(1961).

4) Interference with an easement or profit.

7. Supply the right modal verbs or their substitutes to make the sentences complete

|

1) may 2) has to 3) will 4) must 5) will |

Physical damage As a general rule, nuisance is not actionable per se and actual damage must be proved, subject to the following exceptions: where a presumption of damage can be made, for example, by building a cornice so that it projects over the claimant's land, it may be presumed that damage will be caused to the claimant's land by rain water dripping from the cornice onto the land; interference with an easement, profit a prendre or right of access where there has been acquiescence in certain circumstances. So, private nuisance is concerned with balancing the competing claims of neighbors to use their property as they think fit. However, a distinction must be made between physical damage to property, where such conduct 3)…, subject to the de minimis rule, be a nuisance, and personal discomfort or amenity damage, where the judge will consider many factors to determine the balance. If the conduct complained of causes physical damage to the claimant's property, this 4)… amount to nuisance (subject to any defense available). In St Helens Smelting Co v Tipping (1865), Lord Westbury said that an 'occupier is entitled to expect protection from physical damage no matter where he lives'.

Amenity damage Amenity damage is interference such as noise, smells, dust and vibrations which will interfere with use and enjoyment of land without physically damaging the property. In the case of amenity damage, the degree of interference will be measured against the surrounding circumstances.

8) Describe the types of damage in private nuisance cases. Use cases from the text to illustrate your answer

CASES

Advise your client on his/her liability

1) In St Helens Smelting Co v Tipping (1865) the plaintiff's estate was located in a manufacturing area. Fumes from a copper smelting works damaged the trees on the estate. The distinction was made between physical damage and amenity damage, particularly the nature of the surrounding area and locality.

2) In Halsey v Esso Petroleum Co (1961). The plaintiff's house was in a zone that was classified as residential for planning purposes. The defendant's oil depot was across the road in an industrial zone. There was a combination of physical and amenity damage: acid smuts from the defendant's depot damaged paintwork on the plaintiff's car, clothing and washing on the line; there was a nauseating smell; » noise from the boilers caused the plaintiffs windows and doors to vibrate and prevented him from sleeping. There was also noise from the delivery tankers at night.

3) In Laws v Florinplace Ltd (1981), the defendants opened a sex centre and cinema club which showed explicit sex acts. Local residents sought an injunction.

4) In Christie v Davey (1893), the defendant lived next door to a music teacher. He objected to the noise and retaliated by banging on the walls, beating trays, etc.

5) In Hollywood Silver Fox Farm Ltd v Emmett (1936), the plaintiffs bred silver foxes. If they are disturbed in the breeding season they eat their young. The defendant fired a gun as near as possible to the breeding pens with the malicious intention of causing damage

REVISION AND PRACTICE SECTION

1. You should now write your revision notes for Nuisance. Give your definition to

1. The difference between public and private nuisance 2. Proof of damage 3. Physical damage 4. Amenity damage

2. Using your cards, you should now be able to write a short paragraph in response to each of the following question:

1. What is a tort of private nuisance?

2. What are the elements of private nuisance?

UNIT TWO

After examining the following chart read the text

Nuisance protects those persons who have an interest in the land affected, so only an owner or occupier with an interest in the land can sue. The plaintiff in Khorasandijan v Bush (1993) succeeded without having a proprietary interest in the land. She was being harassed by a former boyfriend. Most of the harassment took place at her mother's home, in which the plaintiff had no proprietary interest. Dillon LJ said that the law had to be reconsidered in the light of changed social conditions. He felt that as the mother could have sued, there was no reason to prevent the daughter from suing. Khorasandijan illustrates an expansionary approach to the tort of nuisance. It was decided at a time when it appeared that it would evolve to protect interests other than land. The case was overruled by Hunter v Canary Wharf (1997). The majority of the House of Lords held that the plaintiff should establish a right to the land affected in order to sue in private nuisance. This restricts nuisance as a tort designed to protect interests in land.

The claimant

1) The creator of the nuisance A person who creates a nuisance by positive conduct may be sued. It is not necessary for the creator of the nuisance to have any interest in the land from which the nuisance emanates. A defendant in trespass need not be a neighbouring landowner and the same should be true in nuisance.

2) The occupier The occupier is the usual defendant in private nuisance. An occupier will be liable for:

1) Persons under his control. (Under the principles of agency and vicarious liability)

2) Independent contractors. Where nuisance is an inevitable or foreseeable consequence of work undertaken by independent contractors, the occupier cannot avoid liability by employing a contractor, as in the case of Mantania v National Provincial Bank Ltd (1936).

3) Actions of a predecessor in title. An occupier who knows or ought reasonably to have known of the existence of a predecessor in title will be liable for continuing the nuisance if he does not abate it. If the nuisance could not reasonably have been discovered, he will not be liable.

4) Actions of trespassers. An occupier is not liable for a nuisance created on his land by a trespasser unless he adopts or continues the nuisance.

5) Acts of nature. At common law, it was thought that an occupier had no duty to abate a nuisance that arose on his land from natural causes. The extent of the obligation was to permit his neighbor access to abate the nuisance. The Privy Council in Goldman v Margrave (1967) established that an occupier is under a duty to do what is reasonable in the circumstances to prevent or minimize a known risk of damage to the neighbor’s property.

3) The landlord A landlord may be liable for a nuisance arising in three types of situation:

(a) Where the landlord authorized the nuisance.

(b) Nuisance existed before the date of the letting.

(c) Where the landlord has an obligation or a right to repair. The law on landlords' liability for nuisance is still developing

Defenses

Consent of the claimant Where the claimant has expressly consented to the nuisance, this is a defense provided it is true consent, i.e. to both the nature and extent of the nuisance. Prescription This is a form of implied consent. Where the defendant has been committing the nuisance for more than twenty years and has done so without force, secrecy or permission (nec vi, nec clam, nec precario), this is a defense against a claimant who has not complained during this time. However, this defense is of little practical application today as the time starts running from the time the particular claimant became aware of the nuisance (Sturges v. Bridgman [1879]). Therefore, it is no defense to argue that the claimant "came into" the nuisance—the fact that a previous occupier of the affected land had not complained does not bind a subsequent occupier. Statutory authority The defendant may have a defense where their actions are in pursuance of a statutory power or duty, though they must take all reasonable steps to keep any nuisance caused to a minimum.

Remedies

At common law, a successful claimant has a right to damages. However, it may well be that the claimant wants the nuisance stopped by an injunction. We should remember that an injunction, being an equitable remedy, lies in the discretion of the court and will only be granted where it is just and equitable to do so. A self-help remedy, abatement, is also available. The claimant may take all reasonable steps to stop the nuisance though, for a variety of reasons, this is usually not advisable.

2. Answer the following questions

1) Who can sue in a tort of nuisance?

2) Who can be sued in a tort of nuisance?

3) When shall the occupier be liable for a tort of nuisance?

4) When is the occupier liable for the actions of others in nuisance?

5) What is the legal position as for the occupier’s liability for acts of nature?

6) What is the liability of the landlord for existing situations?

7) What is the most common remedy for the tort of nuisance?

3. Find the English for

1) право в недвижимости, 2) докучать, причинять беспокойство, 3) развиваться, эволюционировать, 4) отвергать решение по ранее рассмотренному делу с созданием новой нормы прецедентного права, 5) вполне определенное поведение, 6) в соответствии с агентским договором, 7) предыдущий владелец собственности, 8) подразумеваемое согласие, 9) средство судебной защиты по праву справедливости, 10) судебное предписание, судебный запрет

4. Supply the English variant for the Russian words in brackets to make the sentences complete and answer the question: “When is the occupier liable for actions of trespassers?”

Actions of trespassers An occupier is (не нести ответственности за) a nuisance created on his land by a trespasser unless he adopts or continues the nuisance. In Sedleigh-Denfield v O'Callaghan (1940), (границы владений) between the appellant's premises and those of the respondents was a hedge and a ditch, both of which belonged to the respondents. Without informing the respondents, (лицо, нарушившее границы владений) laid a pipe in the ditch. Some three years later the pipe became blocked and the appellant's garden (быть затопленным). The respondents' servants had cleared the ditch out twice yearly. The appellant claimed damages in nuisance. It was held that he would succeed because the respondents knew or ought to have known (о наличии помех) and permitted it to continue without taking prompt and efficient action ( ликвидировать их)

5. Supply the English variant for the Russian words in brackets to make the sentences complete and answer the question: “What is the act of nature?”

Acts of nature At common law, it was thought that an occupier had no duty to abate a nuisance that arose on his land (по естественным причинам). The extent of the obligation was to permit (своему соседу) access to abate the nuisance. The Privy Council in Goldman v Margrave (1967) established that an occupier is under a duty to do what is reasonable in the circumstances to prevent or (сводить к минимуму) a known risk of damage to the neighbor’s property. The appellant was the owner/occupier of land next to the respondents. A tree on the appellant's land (ударить молнией) and caught fire. The appellant took steps to deal with the burning tree, but subsequently left the fire to burn itself out and took no steps to prevent the fire spreading. The fire later revived and spread, (причинить существенный вред) to the respondents' land. The appellant was held to be liable.

6. Analyze the elements of the tort of private nuisance in 200-300 words in the form of a legal precis. Consult the chart below

7. Supply the English variant for the Russian words in brackets to make the sentences complete and answer the question: “When shall a landlord be liable for nuisance?”

A landlord may be liable for a nuisance where the landlord (дает разрешение на) the nuisance. In Sampson v Hodson (1981), a tiled terrace was built over the plaintiff's sitting room and bedroom. The noise (чрезмерный) and it was held that the landlord was liable in nuisance. A landlord, who let flats with poor sound insulation to tenants, was not liable in the tort of nuisance to a tenant whose reasonable (использование) of her flat was interfered with by the ordinary use of an adjoining flat by another (жилец) tenant (Baxter v Camden London Borough Council (No 2) (1998)).

CASES

Advise your client on his/her liability and available defenses

1) In Pride of Derby and Derbyshire Angling Association Ltd v British Celanese Ltd (1953), pollutant sewage from factories reached a river through the effluent pipe of a local authority from the sewage works.

2) In Adams v Ursell (1913), the defendant ran a fish and chip shop. The plaintiff objected to the noise and smells. The defendant tried to argue that the fish and chip shop was of public benefit

3) In Miller v Jackson (1977), cricket had been played on a village ground since 1905. In 1970, houses were built in such a place that cricket balls went into a garden. It was held that there was a nuisance; there was an interference with the reasonable enjoyment of land.

4) In Sturges v Bridgeman (1879), a confectioner and a physician lived next door to each other. The confectioner used two large machines and had done so for more than 20 years. The noise and vibrations had been no problem until the physician built a consulting room at the end of his garden

5) In Allen v Gulf Oil Refining Ltd (1981), a statute authorized the defendants to carry out oil refinement works. The plaintiff complained of noise, smell and vibration.

REVISION AND PRACTICE SECTION

1. You should now write your revision notes for nuisance. Give the definition to

1) Claimants and Defendants 2) Defenses in Nuisance 3) Remedies for nuisance

2. Using your cards, you should now be able to write a short paragraph in response to each of the following questions

1) Who may bring a claim in private nuisance? 2) Who may be sued and what defenses may they have? 3) Explain the remedies available for private nuisance

UNIT THREE

1. Read the following text

Public nuisance

A public nuisance is a crime as well as a tort. The remedy for a public nuisance is a prosecution or relator action by the Attorney General on behalf of the public. A claimant who suffers particular damage, over and above the damage suffered by the rest of the public, may maintain an action in public nuisance. Public nuisance has been defined as 'an act or omission which materially affects the reasonable comfort of a class of Her Majesty's subjects', per Romer LJ in AG v PYA Quarries Ltd (1957).

Public nuisance is most important in relation to highways

What obstructions are actionable? 1) A temporary or permanent obstruction that is reasonable in amount and duration will not be a nuisance. 2) An obstruction which creates a foreseeable danger will amount to a nuisance.

Damage

The claimant must suffer direct and substantial damage to bring an action in public nuisance. The following have been held to be special damage: 1) additional transport costs, caused by an obstruction, see Rose v Miles (1815); 2) obstructing access to a coffee shop, see Benjamin v Storr (1874); and 3) obstructing the view of a procession so that the plaintiff lost profit on renting a room, see Campbell v Paddington BC (1911). Tarry v Ashton (1876) is an example of public nuisance being capable of amounting to a tort of strict liability. The defendant's lamp projected over the highway. An independent contractor repaired the lamp but it fell on the plaintiff. The defendant was found liable in the absence of fault.

Similarly, in Wringe v Cohen (1940), a wall of the defendants' house, which was let to weekly tenants, collapsed. The defendants, who were liable to keep the house in a good state of repair, did not know that the wall was in a dangerous condition but were nevertheless held to be liable. In Mint v Good (1951), again, a wall in front of houses which were let to weekly tenants collapsed, although there was no express agreement between the landlord and tenant as to repair. The landlord was held to be liable.

Liability in tort is generally dependent upon proof of fault on the part of the defendant. However, there is a limited amount of strict liability, principally concerning liability for certain extra-hazardous activities. This liability may be imposed by statute (for example, the Nuclear Installations Act 1965, the Control of Pollution Act 1974) or under the common law rule established in Rylands v. Fletcher [1868].

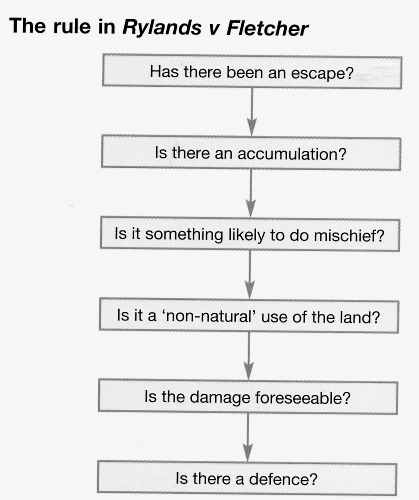

The rule in Rylands v. Fletcher

Under this rule: A person who is in occupation of land and brings onto that land something that is not naturally there, and does so for his own non-natural use, and that thing is likely to do mischief should it escape, then that person will be liable for the consequences of any such escape, even in the absence of any fault on his part. The various elements of this rule require further explanation.

1) The defendant must have been in occupation (i.e. in control) of the land from which the thing escapes.

2) The thing must not have been naturally present on the land [e.g. self-sown trees and plants are naturally present whereas deliberately cultivated ones are not).

3) The thing must have been brought onto the land by the defendant for his own use, though not necessarily for his own benefit.

4) The defendant must have been using the land is some non-natural way. i.e. he must have been engaged in some special use bringing with it an increased danger to others, and not merely the ordinary use of land or that which is for the general benefit of the community (Rickards v. Lothian [1913]]. This considerably limits the scope of the rule in practice.

5) The thing must be likely to do mischief should it escape. This does not mean it has to be inherently dangerous; merely that it is potentially dangerous should it escape in ал uncontrolled way.

6) The thing must escape, i.e. leave the confines of the defendant's land (Read v. Lyons (J) & Co Ltd [1947]). Where there is no escape, the claimant must rely on the principles of negligence, occupiers' liability or nuisance as appropriate.

Defences While liability under the rule is strict, it is not absolute, and there are five main defences available:

1) The defendant is not liable where the escape is due to an Act of God. This applies where the escape is the result of natural causes without any human intervention, and such natural events were not reasonably foreseeable (Tennent v. Earl of Glasgow [1864])

2) The defendant may be able to avoid liability where he was acting under statutory authority. 3) The defendant will not be liable where the escape is due to the unforeseeable act of a stranger (e.g. a trespasser).

4) The defendant will not be liable where the claimant had, expressly or impliedly, consented to the thing being brought onto the land or to its remaining there. Thus, while "coming into" the situation is no defense to an action in nuisance; it may be a defense to an action based on the rule. Consent here means true consent, in the sense that the claimant was aware not only of the presence of the thing but also of its potential for mischief should it escape.

5) The defendant will not be liable where the escape is due to the sole fault of the claimant. Where the escape is partly due to the fault of the claimant, contributory negligence will apply.

2. Answer the following questions

1. What is public nuisance?

2. When is public nuisance a crime\ a tort?

3. What is the remedy for public nuisance?

4. How is the damage assessed in a tort of public nuisance?

5. What is the most important wrongdoing in a tort of public nuisance?

6. What type of damage shall be suffered in an action of public nuisance?

7. When does a tort of nuisance give rise to strict liability?

8. What are the main principles formulated in Rylands v Fletcher ?

9. What does ‘a defence of coming into a situation’ mean? Is it a valid defence?

10. What is the range of application of statutory authority defence?

3. Find the English for

1) реляторное действие, 2) возбуждать иск, 3) создание временного или постоянного препятствия будут квалифицироваться как…, 4) понести прямой и значительный ущерб, 5) некоторые действия представляющие особую опасность для окружающих 6) нанесет вред, покинув мести нахождения (расположения) 7) при использовании имущества не сопряженного с выгодой для себя, 8) (не) представлять опасности по своей природе, 9) обстоятельства непреодолимой силы, 10) распоряжение властей

4. Read the case and answer the questions: “What is the rule in a test for public nuisance?” and “What are the limits to the rule?”

The rule was originally formulated by Blackburn J in Rylands v Fletcher in the following terms: The person who for his own purposes brings on his land and collects and keeps there anything likely to do mischief if it escapes, must keep it in at his own peril and, if he does not do so, is prima facie answerable for all the damage which is the natural consequence of the escape. This was approved by the House of Lords, and the condition that there must be a 'non-natural user' was added by Lord Cairns. Limits of the rule may be summarized as follows: 1) There must have been an escape of something 'likely to do mischief, 2) There must have been a non-natural use of the land. As for 'Anything likely to do mischief if it escapes' this is a question of fact in each case. However, things which have been held to be within the rule include electricity, gas which was likely to pollute water supplies, explosives, fumes and water.

5. Read the case and answer the question: “ What is an ‘escape’ in the law of tort?”

There must be an escape In Read v Lyons & Co Ltd (1947), it was said that escape, for the purposes of applying the proposition in Rylands v Fletcher, means 'escape from a place where the defendant has occupation or control over land to a place which is outside his occupation or control', per Lord Simon, and 'there must be the escape of something from one man's close to another man's close', per Lord Macmillan. In Read v Lyons, the plaintiff was a munitions worker who was injured by an exploding shell while in the defendant's munitions factory. It was held that there had not been an escape of a dangerous thing, so the defendant could not be liable under Rylands v Fletcher. The claimant must prove not only that there has been an escape, but also that damage is a natural consequence of the escape.

6. Read the case and answer the question: “When is the respondent liable for 'bringing onto the land and keeping it there' ?