- •Кафедра английского языка № 4

- •Contents

- •Vocabulary

- •Vision n

- •Improving your Mind Maps

- •Vocabulary

- •Vertical organisational structure

- •Vocabulary

- •Individually tailored products

- •Vocabulary

- •Income-sensitive goods

- •Vocabulary

- •In an innovation economy, it's no longer a cure-all

- •Vocabulary

- •Ideagora, a Marketplace for Minds

- •Ideas and innovations are increasingly coming from outside company walls—and Web-based virtual talent pools are stepping in to fill the need

- •Vocabulary

- •Incremental innovation

- •Venture capital

- •If you want to create a solid brand, you need to invest steadily and consistently in the process. Patience and fortitude will pay

- •Brand tribe; brand dilution; flagship brand; brand portfolio; copycat; brand extension;, brand image; brand revitalization; brand extension; brand awareness

- •Vocabulary

Contents

UNIT 1. GREAT MANAGERS AND BIG IDEAS 5

UNIT 2. THE NEW ORGANISATION 22

UNIT 3. KEEP THE CUSTOMER SATISFIED 38

UNIT 4. CASE STUDY – DELL 56

UNIT 5. QUALITY MANAGEMENT 71

UNIT 6. SIX SIGMA vs INNOVATION 83

UNIT 7. INNOVATION MANAGEMENT 101

UNIT 8. BRAND MANAGEMENT 126

UNIT 1. GREAT MANAGERS AND BIG IDEAS

|

Competencies:

|

|

|

|

READING AND SPEAKING (1) |

What great managers of the past century do you know?

What are they famous for?

What is their contribution to the art and science of management?

What great management ideas can you name?

1. Put the jumbled paragraphs of the text in the correct chronological order.

The Big Ideas

a)

Quality.W. Edwards Deming hated American management style, and by the 1980s American managers came to love him for it. Deming, the traveling evangelist of quality, had been ignored by American corporations in the late 1940s when he tried to interest them in his statistical methods for process control. So in 1950 he took his tent show to Japan, where he railed against American evils like competition (cooperation was more constructive), production quotas (which sacrificed quality for quantity), and end-of-the-line inspections (which in effect plan for defects rather than design processes to prevent them). Having lost everything in the war, Japanese manufacturers proved receptive and soon were taking market share from American companies. When an American television program "discovered" Deming in 1980, business was finally ready to listen to it.

b)

Leadership. The most ingenious corporate structure means nothing unless someone leads it well. One of the earliest and most original thinkers on leadership issues was Mary Parker Follett, a New England social worker trained in political science who became an adviser to business leaders in the 1920s and 1930s. Follett preferred constructive conflict to compromise. She believed employees should have a voice in how things are done, but only if they share in the responsibility. And half a century before the business schools got around to it, she spoke of managers who lead with shared vision and common purpose. No wonder Peter Drucker has called her the "prophet of management."

c)

Scientific

management. Frederick

Winslow Taylor is the management thinker humanists still love to

hate, although he's been dead since 1915. His system of scientific

management, they say, dehumanizes workers and reduces management to a

matter of measurem ents.

But ever since Taylor's methods of "working smarter" first

made him famous at the turn of the century, our appetite for greater

productivity has been insatiable.

ents.

But ever since Taylor's methods of "working smarter" first

made him famous at the turn of the century, our appetite for greater

productivity has been insatiable.

Taylor first got out his stopwatch in 1881 in the hope that science could end a tug of war over piece rates. As a young foreman at Midvale Steel in Philadelphia, he was expected to cut rates when production was high, but he knew that workers would react by holding down production when rates fell. Seeking a Platonic ideal of steelmaking, Taylor carefully isolated and timed each step in the process. Along the way, he saw ways to improve the system — by rearranging the shop, modifying a tool, or eliminating a movement. He supplied instruction cards so that the machinist didn't need to think: Taylor had done the thinking for him. Taylor spent the next 30 years refining his principles of scientific management. When in 1910 Louis Brandeis publicized Taylor's ideas to expose the wasteful habits of the railroads, the efficiency era was born. "In the past the man was first," Taylor wrote. "In the future the system must be first."

d)

Modern Corporation. Turning a random assemblage of car companies into what has been America's largest corporation for the better part of seven decades is impressive, but it didn't earn Alfred Sloan Jr. a place on this list. What did was his design for General Motors — multiple divisions controlled and supported by a central core. That set the standard for the modern decentralized corporation.

e)

Management guru. If Peter Drucker's name comes up frequently in these pages, it might be because he has chronicled oranticipated almost every major management landmark, from GM at the close of the Sloan era (inConcept of the Corporation) to knowledge workers (a term he coined 40 years ago).The Practice of Management,first published in 1954, is still going strong. The original management guru (a word Drucker says people use only because "charlatan" is too long to fit in a headline), Drucker has done more to legitimize management as a profession than a business school full of theorists.

f)

Laborrights.Not all big ideas about managing have come from managers. No one has fought harder in this century than labor unions to make work safer and more fair. And no one better personifies the nobler side of labor's struggles than Walter Reuther. He negotiated the 1955 merger of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (which he led) with the American Federation of Labor and broadened labor's influence. In 34 years with the United Auto Workers, he championed the rights of workers to medical coverage, pensions, and unemployment benefits. The boss was still the boss, but the workers had found a voice.

g)

Reengineering. Michael Hammer and James Champy set the business world on fire in the early '90s, selling two million copies of their manifesto,Reengineering the Corporationand FORTUNE, we admit, helped to fan the flames. Now that reengineering is about as popular as Linda Tripp, it's fair to ask, what were we thinking? First, Hammer and Champy's vision was no mere cost-cutting tool but the first large-scale, systematic application of information technology to management. By re-imagining business processes, companies could put back together tasks that Taylor and Co. had pulled apart, building responsibility into jobs that used to pass the buck. Second, no one said reengineering would be easy. In fact, one critic has compared it to chemotherapy ― a radical treatment that destroys a lot along the way. Half-hearted attempts pretty much guaranteed failure. And there were plenty of failures, not to mention that companies used the idea to justify willy-nilly downsizing. As the authors later acknowledged, they hadn't paid enough attention to the people.

h)

Assembly line. Henry Ford gets his due elsewhere in this magazine, so why mention him here? Two words: mass production. In 1909, Ford produced almost 14,000 cars; just five years later the moving assembly line had increased output to over 230,000. Ford's moving assembly line upped Taylor's ante: Taylor tested the maximum a man could produce; Ford's assembly line had its own speed, and the workers had to adapt to it.

i)

Managing by the numbers.Add, subtract. That pretty much sums up 30 years of finance-driven management. The '60s brought the conglomerate era, when companies like ITT branched out into rental cars, hotels, and Wonder Bread bakeries. It was no drawback to be ignorant about these new businesses, the gods of finance proclaimed — with good data, you could manage anything. Bigger was better, and being on top of the FORTUNE 500 was best. But the conglomerate strategy did not stand the test of time. Harold Geneen, the king of the conglomerates, managed to hold ITT together until he stepped down as CEO in 1977. Disassembly followed. By the 1980s the momentum had reversed, so the equation 2 + 2 = 5 was now 5 – 2= 7. What fueled the frenzy of the Deal Decade were new fads in financing — leveraged buyouts and their new currency, junk bonds. By piling on debt, takeover artists aimed to force managers to eliminate waste and reawaken the entrepreneurial impulse in bloated businesses. Although investors saw gains, often such deals left companies strapped for capital to invest in the future or sent once stable businesses into bankruptcy.

j)

Knowledge management.If the Internet economy has taught us anything, it's that the physical world Frederick Taylor lived in determines less and less of what we value. A good idea, especially one that is well timed, has almost unprecedented worth. It follows, then, that the stuff between workers' ears, obviated by Taylor and barely tolerated by Ford, becomes treasure to today's managers. Now the challenge for managers is how to capture, harness, and develop that knowledge profitably.

k)

Brand management. It's tough out there in consumer-products land: so many products, so little supermarket shelf space. But those crowded shelves are a testament of sorts to the glory of brands. And all those brands, in their sometimes maddening variety, owe their vitality to an idea that surfaced at Procter & Gamble way back in 1931. The poor showing of Camay against the well-established Ivory soap led P&G manager (and future CEO) Neil McElroy to suggest that what Camay needed was an advocate. This "one man, one brand" system turned company men into entrepreneurs who went all out for their product, a system that left its mark on products the world over.

Fortune, November 22, 1999

Notes

-

Congress of Industrial Orga-nizations (CIO)

Конгресс производственных профсоюзов (КПП)

American Federation of Labour (AFL)

Американская федерация труда (АФТ)

United Auto Workers (UAW) [United Automobile, Aereo-space and Agricultural Workers of America]

Объединенный профсоюз работ-ников автомобильной промыш-ленности (Объединенный проф-союз работников автомобильной, авиакосмической промышленно-сти и сельскохозяйственного машиностроения)

Linda Tripp

Monica Lewinsky’s friend who recorded telephone conversations with Lewinsky in late 1977 which eventually led to the impeachment of President Clinton

2. Discuss the following questions.

What are the aims of the total quality management (TQM) and re-engineering?

What management concept is behind creating a conglomerate and a focused business?

What is Taylorism?

What does synergy mean in management?

What big ideas were developed in the car industry?

What is the contribution of Proctor & Gamble to the management theory and practice?

|

|

READING AND SPEAKING (2) |

3. Scan the following article and say what conclusions were made in the study “Management Practice and Productivity.”

What witch doctors?

Maybe management theory is not hocus pocus after all

ONCE again, scepticism about management theory — at least as business schools teach it — is growing. In his latest book, “The Future of Management”, Gary Hamel notes that several top executives — including Sergey Brin and Larry Page (the “Google Guys”) and John Mackey of Whole Foods Market — did not go to business school. Donald Trump is a Wharton alumnus, but you would not guess it from his new bestseller, “Think Big and Kick Ass in Business and Life”, with its street-fighter's advice to always get even and never marry without a prenuptial agreement. Rakesh Khurana’s new book about business schools, “From Higher Aims to Hired Hands”, charts how management science declined from a serious intellectual endeavour to a slapdash set of potted theories.

All of this seems in keeping with the sceptical title of a book about management theorists written a decade ago by two journalists at The Economist(one now its editor-in-chief) called “The Witch Doctors”.

A new study begs to differ, arguing that firms implementing sound management practice have higher labour productivity, sales growth and return on capital. “Improved management practice is one of the most effective ways for a firm to outperform its peers,” concludes the study, “Management Practice and Productivity: Why They Matter”. That this is at all controversial shows how far management theory has fallen from its peak early in the 20th century, when it seemed that the science of running firms would be as rigorous as, say, applied physics.

To prove their case, the study’s authors, including Nick Bloom of Stanford University and John Van Reenen of the London School of Economics, have interviewed managers at some 4,000 companies in America, Europe and Asia. (This advances an earlier study of 700 firms in America, Britain, France and Germany.)

Using the interviews, the authors rated management practices on a scale of one to five (with one being worst and five best) across 18 categories within three broad areas: shop-floor operations, performance management and talent management. There seems to be no magic bullet: a firm’s average score across all 18 dimensions was the best guide to whether it would outperform its peers.

Many of the detailed findings are more surprising. In every part of the world, the spread between the best and worst run firms is wide. American firms tend to be best run, with an average score of 3.3, and Indian firms are the worst, with an average score of 2.62. But the best 20% of firms in India performed better than the average American firm, and the best 10% of Indian firms outscored 75% of American firms.

In every country surveyed, businesses owned by multinationals tend to be better run than their locally owned peers. Multinational firms in India scored better than any other businesses except American multinationals operating in America. When a local firm is acquired by a multinational, the quality of its management tends to rise.

Multinationals have an edge, the authors argue, because they “have been forced to take a systematic approach to management. Only by having strong, effective management practices in place have they been able to replicate the same standards of performance across different regions, cultures and markets.”

Another driver of better management practice is competition, which has the strongest effects on the worst managed companies. In many countries, weak competition allows too many underperforming, poorly managed firms to survive. When firms with a score of 2 or less are excluded, the average score across the board rises from 2.62 to 2.88 in India and from 2.64 to 2.91 in Greece, compared with a small rise from 3 to 3.09 in more competitive Britain and from 3.3 to 3.33 in super competitive America.

One other notable finding: firms with dispersed ownership scored best and performed best, whilst those owned and run by their founders or members of the founder’s family performed relatively poorly. Worst of all were family-owned firms run by the founder’s eldest son, with an average management score of 2.53, further proof of the wisdom of Warren Buffett’s opposition to the hereditary principle, which he calls the “lucky sperm club”, and describes as akin to “choosing the 2020 Olympic team by picking the eldest sons of the gold-medal winners in the 2000 Olympics.”

Economist.com, Nov 13th, 2007

Note

The Witch Doctors — the book by John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge, the Economist editors (the former became editor-in-chief in 2006).

4. Answer the following questions.

Why is scepticism to management theory growing?

In what way is the new study different?

What methods did the authors use?

What areas of management did the survey cover?

Which companies were better run in every country?

What other factors tend to improve management practices?

Is the form of ownership important for corporate performance?

What is Warren Buffett’s attitude to hereditary principle? Do you agree with him?

5. Explain the following.

a Wharton alumnus

to get even

a serious intellectual endeavour

a slapdash set of potted theories

all of this seems in keeping with

to prove one’s case

there seems to be no magic bullet

shop-floor operations

performance management

dispersed ownership

underperforming firms

to replicate the same standards of performance

I T

MATTERS

T

MATTERS

6. Find information in the Internet about a) Donald Trump, b) John Mackey of Whole Foods Market; c) Sergey Brin and Larry Page; d) some other famous entrepreneur. Make mini-presentations about those famous people and their businesses(Portfolio entry).

|

|

TRANSLATION

|

7. Translate the text “The Big Ideas” orally.

8. Translate the text “What Witch Doctors?” in writing.

9. Translate the following sentences into Russian.

Propping up weaker companies hurts the strong ones, since they then have to cope with subsidized competitors.

Tapping into the knowledge base of GE is a negotiating tool or benefit of doing business, not an end in itself. Bringing customers to GE’s research and development centers or famed training facilities in Crotonville, for example, is meant to improve productivity, not provide free field trips.

That the products which the business units select to sell globally, will continue to be tailored to local markets only adds to the complexity. Internal "disruption" is already affecting sales.

Whatever detailed rules the SEC agrees are almost certain to be challenged by the lawyers, who are not a group lacking in legal representation.

Gone are the days when Vivendi Universal’s top executives hobnobbed with pop stars and gave interviews to Rolling Stone. What Jean-Marie Messier once trumpeted as the core of his ill-starred vision of a global media and communications empire has become a faint echo after his departure as chief executive and almost two years of aggressive restructuring that has rescued the French conglomerate from the brink of collapse.

As Microsoft focuses increasingly on developing an image as an innovator — the company is trying to fend off not only antitrust threats but also the competitive challenge to Windows from the rise of open-source software like Linux — it has adjusted its advertising strategy in recent years. While Microsoft in the past had predominantly used product-specific advertising, the company is now spending about one-quarter of its ad budget on a brand-building campaign that seeks to give Microsoft a more human face.

|

|

LANGUAGE FOCUS |

10. Suggest the Russian for the following.

a moving assembly line, to roll off the assembly line, to end a tug of war over smth; to expose wasteful habits and inefficiencies; leadership issues; the leader’s vision; multiple divisions controlled from the central core; to get one’s due; to dodge price controls; sprawling empires of HR departments; bloated businesses; bloated (swollen) budget; to branch out into hotels and bakeries; to impose import quotas; to dodge oil production quotas; to build responsibility into jobs; a landmark deal; to lead with shared vision and common purpose; the momentum has reversed; to fuel the frenzy; to be a testament to the glory of brands; finance-driven management; to step down as CEO; to outscore ; shop-floor operations; performance management; to rate management practices

11. Translate the following into English.

управление качеством; устанавливать обязательные для членов нефтяного картеля квоты на добычу; сосредоточить внимание на основных направлениях деятельности; устранить все дефекты в автомобиле на конечной стадии производства; подливать масла в огонь; управление торговой маркой; обоснованное сокращение размеров компании; переосмысление и реорганизация всего процесса; крупномасштабное сокращение издержек; разросшиеся отделы; обсуждать показатели работы компании; уйти с поста главного исполнительного директора; использовать систему поставок «точно в срок»; иметь преимущество; недостаточно хорошо работающие фирмы; обгонять по показателям аналогичные фирмы

12. Define the adjectives shown in the chart and give possible combinations with the nouns in the box.

diamond, politician, businessmen, appetite, mind, leather, population, ambition, attempt, toy, signature, person, solution, desire, tool, pleasure, companies, money, speech

|

adjectives |

definition |

collocations with nouns |

|

insatiable |

|

|

|

ingenious |

|

|

|

indigenous |

|

|

|

genuine |

|

|

|

half-hearted |

|

|

|

faint-hearted |

|

|

|

hard-nosed |

|

|

13. Give the English for the following using the words of the unit.

Кто бы мог подумать, что новая теория в области управления разожжет страсти в деловом мире и заставит многих переосмыслить все основы бизнеса.

Нельзя было ожидать, что новые веяния в менеджменте заставят управленцев заняться сокращением издержек и устранением потерь.

Вскоре после окончания войны президент Франции Шарль де Голль (Charles de Gaulles) распорядился о создании собственной компьютерной фирмы «Буль» (Bull), призванной стать гордостью национальной индустрии и бросить вызов доминирующему положению американской компании Ай-Би-Эм (IBM).

Многие конгломераты начинают избавляться от неприбыльных предприятий и уделять внимание основному виду деятельности, в которой компания добилась преимущества в конкурентоспособности на мировом рынке.

Использование заемных средств при выкупе компаний расширяет финансовые возможности компании в таких операциях и позволяет захватывать объекты поглощений, которые оказались бы ей не по зубам, если бы она опиралась на собственный капитал.

Что касается стратегии, то компания «Джи-И Кэпитал» (GE Capital) пошла в Европе тем же путем, который обеспечил ей успех в США: захват недостаточно хорошо работающих предприятий в области лизинга, страхования или потребительского кредита. В случае необходимости компания назначала новое руководство и внедряла более эффективную технологию и методы работы. Она объединяла компании одного профиля для достижения эффекта масштаба, ставя нелегкие задачи перед менеджерами этих компаний.

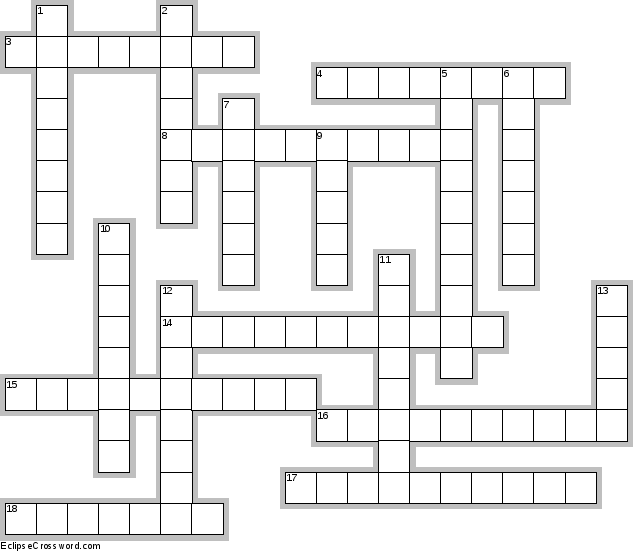

Solve the following crossword puzzle.

Across

3. a plant which is processing oil, metals or sugar

4. milestone

8. official examination to check if everything is as it should be

14. arrogant, domineering

15. local, belonging to a place or region

16. deprive of human qualities as pity, kindness and creativity

17. trade-off

18. swollen

Down

1. tarnish, defame

2. of the original stock; true, authentic

5. governance

6. a new candidate

7. a valuable or desirable thing, property, resources

9. to train and instruct

10. a person who fights for smb. or for a cause

11. a series of meetings for intensive study

12. insurance

13. evade

|

|

BUSINESS SKILLS |

15. Read the following articles and pick out information about new ways to solve corporate problems. Express your opinion of these innovations.

Shall We Play A Game?

Playing war games can give companies new perspectives on complex problems

WAR GAMES are commonly used by the military to evaluate strategies, explore scenarios and reveal unexpected weaknesses. American ships and aircraft have just begun two weeks of war games in the Gulf, prompting protests from Iran, and last week South Korea carried out an annual computerised war-game exercise.

Might war games deserve a greater role in business? Military analogies abound in the corporate world. Plenty of bosses look to Sun Tzu, an ancient Chinese general, for management tips. And in business, as in war, outcomes depend on what others do, as well as one's own actions. Yet many firms fail to think systematically about how rivals will react to their plans — and traditional planning does a poor job of taking competitors' responses into account, says John McDermott, head of strategy at Xerox, an office-equipment company. Corporate war games, which simulate the interactions of multiple actors in a market, provide a better way to do so.

Such games have two chief characteristics. First, players break into teams and take on the roles of fierce competitors (and sometimes other constituencies, such as customers). Second, the games involve several turns, allowing competitors not just to draw up their own strategies but to respond to the choices of others. Their popularity is rising. Booz Allen Hamilton (BAH), a consultancy, is running 100 war games a year, up from around 50 three years ago. Open Options, a Canadian strategy consultancy, has been going since 1996 and its revenue doubled last year.

Games can vary greatly in sophistication. Fuld & Company, a consultancy, recently ran a simple public game devoted to social-networking websites at the London Business School. Student teams took on the roles of YouTube, MySpace, Second Life and Facebook, and devised strategies that were judged by a panel of outside experts. Halfway through, organisers spiced things up with the announcement that Apple had entered the market with iTown, a fictitious online community for users of its iTunes music service. (If the game is an accurate guide to the future, MySpace is sitting pretty and Facebook is in trouble.)

BAH introduces a quantitative element into its games, calculating the effect of each team's strategy on their company's profits and stockmarket value at the end of each turn. Open Options takes the number-crunching further still. To help Xerox understand the market dynamics of the print and copy industry, it ran a one-day workshop in which teams from Xerox took the roles of the big companies in the market, itself included. Each team identified the things “their” company could do to change its strategy and drew up a list of its desired outcomes; these “preference trees” were shared with the other teams and fine-tuned. The results were then pumped into Open Options' proprietary software tools, which played out interactions between the companies and produced a range of possible outcomes.

Mr McDermott says the game's predictive power was astonishing: one forecast, that a company would start to acquire a certain group of assets within the industry, came true within six months. By shedding light on areas where companies have different priorities, the concept of preference trees helps to highlight potential trade-offs, as well as competition. Open Options charges North American clients roughly $100,000 for an engagement. “The bang for buck was outstanding,” says Mr McDermott.

The secret of successful war-gaming does not simply lie in mathematics, however. Interaction, not algebra, is the best way to win support for a new strategy. Game-players must be senior for the same reason — although having the top boss on a team can stifle feedback. Strategies also have to capture competitors' hard-to-quantify corporate cultures: when designing a game, BAH seeks out employees at its clients who have actually worked at competitors for that reason. But perhaps war games' greatest value lies in the way they encourage managers to think differently about the consequences of their actions. “To know your enemy, you must become your enemy,” as Sun Tzu would say.

The Economist, 31 May 2007

Piecing Things Together

What companies can learn from playing with Lego

WHEN recruiting at British universities, PricewaterhouseCoopers, a consultancy, presents candidates with an unusual exercise. They are asked to build a tall and sturdy tower using the smallest possible number of snap-together Lego bricks. Similarly, at Google Games, a recruiting event first staged by the search-engine giant in April, candidates are invited to build Lego bridges — the stronger the better. In each case, the company is trying to convey the idea that it offers a creative, fun working environment. “It was as much advertising as a way of trying to get recruits,” says Brett Daniel, a student at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign who built the Google Games' weakest bridge.

The eponymous Danish firm, based in Billund, Denmark, has embraced the corporate use of its coloured plastic bricks. As part of a scheme called “Serious Play” it is certifying a growing number of professional Lego consultants, now present in 25 countries. They coach managers by getting them to build “metaphorical abstractions” of such things as corporate strategy, says Lego's Jesper Jensen, who runs the scheme. Hisham El-Gamal of Quest, a management consultancy based in Cairo that offers Serious Play workshops, says demand for the two-day, $7,000 courses is booming.

Firms

in crisis, such as those besmirched by scandal or in the throes of a

takeover, tend to be most receptive to the idea of Lego workshops,

says François de Boissezon of Imagics, a consultancy based in

Brussels. The results can be embarrassing, particularly for senior

managers. Tsai Yu-Chen of UGene Mentor, a Serious Play consultancy

based in Taipei, says a common exercise is modelling, but not naming,

“the people you hate most”. One chief executive was modelled as a

figure so fat that he blocked a hallway, suggesting he was clogging

up the company.

Firms

in crisis, such as those besmirched by scandal or in the throes of a

takeover, tend to be most receptive to the idea of Lego workshops,

says François de Boissezon of Imagics, a consultancy based in

Brussels. The results can be embarrassing, particularly for senior

managers. Tsai Yu-Chen of UGene Mentor, a Serious Play consultancy

based in Taipei, says a common exercise is modelling, but not naming,

“the people you hate most”. One chief executive was modelled as a

figure so fat that he blocked a hallway, suggesting he was clogging

up the company.

Lego workshops are effective because child-like play is a form of instinctive behaviour not regulated by conscious thought, says Lucio Margulis of Juego Serio, a consultancy in Buenos Aires. This produces “Eureka” moments: a perfectionist who realises the absurdity of frustration over an imperfect Lego construction; the owner of a firm with dismal customer relations who models headquarters as a fort under siege; or an overbearing boss who depicts his staff as soldiers headed into battle. Even in the office, it seems, Lego has a part to play.

The Economist, 5thJuly 2007

|

|

get real

|

Consider such ideas as scenario planning, change management, active inertia, benchmarking, economies of scale and economies of scope, etc. Use computer slides to illustrate or emphasize what you are going to say.

16. Read the passages and fill in the gaps with the names of people who have made a name in management.

1. He reminded us again and again that responsible management is not about buzzwords. It's not about fads. Ultimately, it is not even about developing new products or fattening the bottom line (although he believed those things are important).

Rather, it is about far more fundamental tenets — a philosophy that grew directly out of [________]'s experience as a young writer who had witnessed the rise of Nazi Germany (which in the early 1930s banned and burned the Austria native's work).

[________] wrote that management, at its core, "deals with people, their values, their growth and development—and this makes it a humanity. So does its concern with, and impact on, social structure and the community. Indeed, as everyone has learned who…has been working with managers of all kinds of institutions for long years, management is deeply involved in moral concerns — the nature of man, good, and evil."

2. Some innovators, like Thomas Edison and Alexander Graham Bell, develop products that change the way we live. Others, such as Martin Luther King Jr., force us to see the world through a new moral lens. [________]’s contribution is both more abstract and more elemental: He invented the very idea of the modern American corporation. [________] was the first Organization Man, a visionary devoted to bringing discipline to the impulsive, informal, often chaotic capitalist enterprise of the early 20th century. [________] saw that the business of business could be rationalized, the output measured, and managers rewarded in a way that pushed them to reach for excellence. His ideas, which are now the model for virtually every large corporation, are almost invisible because of their ubiquity. But when he introduced these principles to General Motors Corp. in the 90s and 1930s, they were revolutionary.

3. [_________] is known as the father of the Japanese post-war industrial revival and was regarded by many as the leading quality guru in the United States. Trained as a statistician, his expertise was used during World War II to assist the United States in its effort to improve the quality of war materials.

He was invited to Japan at the end of World War II by Japanese industrial leaders and engineers. They asked [________] how long it would take to shift the perception of the world from the existing paradigm that Japan produced cheap, shoddy imitations to one of producing innovative quality products.

[_________] told the group that if they would follow his directions, they could achieve the desired outcome in five years. Few of the leaders believed him.

4. [_________] didn't invent the automobile, but he invented the automobile business. When he founded the [_________] Motor Co. in 1903, cars were fussy, unreliable, costly novelties. [_________]'s genius was to make them simple, solid, and inexpensive necessities. In so doing, he built the largest industrial organization of the early 20th century and amassed a personal fortune of $1 billion ($36 billion in today's dollars), but he also placed himself at the forefront of a social revolution that had an immeasurable impact on American life. When he got his Model T rolling in 1908, the horse disappeared so fast that the conversion of acreage from hay to other crops is said to have caused an agricultural revolution. And that was only the beginning.

5. [_________] is usually portrayed as the consummate computer geek. Editorial cartoonists and magazine illustrators love to caricature his dweeby spectacles, intransigent hair, and quaintly ill-fitting clothes. Business journalists relish describing his idiosyncratic physical mannerisms and his goofy, jargon-laced speech. Indeed, [_________] himself seems to cultivate a nerdy image.

But the reality is that [_________] is, if anything, the quintessential fin de siecle businessman — a hypercompetitor who combines equal parts technologist, entrepreneur, and corporate architect. Though it's been decades since he actually wrote computer code, he still peruses the work of key programmers and makes detailed suggestions for specific products. Perhaps the shrewdest business strategist of the last quarter of the century, [_________] has flummoxed much larger competitors like IBM and found ways to steal the march on brilliant IT innovators like Apple and Netscape. And unlike most techno-entrepreneurs of his generation, his skills as an imaginative manager and leader have kept pace with his company's breakneck growth.

17. Make a mini-presentation about the person, who you believe has

made a significant contribution to the theory and/or practice of

management. (Portfolio

entry).

17. Make a mini-presentation about the person, who you believe has

made a significant contribution to the theory and/or practice of

management. (Portfolio

entry).

R EFLECTION

SPOT

EFLECTION

SPOT

What have you learned from the Unit? What competencies did it help you develop?