2004 The Dark Tower VII The Dark Tower

.pdfHARRY POTTER MODEL

SERIAL #465-17-CC NDJKR

“Don’t Mess with the 449!”

We’ll Kick the “Slytherin” Out of You!

There were two dozen sneetches in the crate, packed like eggs in little nests of plastic excelsior. None of Roland’s band had had the opportunity to study live ones closely during

their battle with the Wolves, but now they had a good swatch of time during which they could indulge their most natural interests and curiosities. Each took up a sneetch. They were about the size of tennis balls, but a great deal heavier. Their surfaces had been gridded, making them resemble globes marked with lines of latitude and longitude. Although they looked like steel, the surfaces had a faint giving quality, like very hard rubber.

There was an ID-plate on each sneetch and a button beside it. “That wakes it up,” Eddie murmured, and Jake nodded. There was also a small depressed area in the curved surface, just the right size for a finger. Jake pushed it without the slightest worry that the thing

would explode, or maybe extrude a mini-buzzsaw that would cut off his fingers. You used the button at the bottom of the depression to access the programming. He didn’t know how

he knew that, but he most certainly did.

A curved section of the sneetch’s surface slid away with a faintAuowwm! sound.

Revealed were four tiny lights, three of them dark and one flashing slow amber pulses.

There were seven windows, now showing0 00 00 00 . Beneath each was a button so small that you’d need something like the end of a straightened paperclip to push it. “The size of a bug’s asshole,” as Eddie grumbled later on, while trying to program one. To the right of the

windows were another two buttons, these markedS andW .

Jake showed it to Roland. “This one’sSET and the other one’sWAIT . Do you think so? I think so.”

Roland nodded. He’d never seen such a weapon before—not close up, at any rate—but, coupled with the windows, he thought the use of the buttons was obvious. And he thought the sneetches might be useful in a way the long-shooters with their atom-shells would not be.SET andWAIT .

SET…andWAIT .

“Did Ted and his two pals leave all this stuff for us here?” Susannah asked.

Roland hardly thought it mattered who’d left it—it was here and that was enough—but he nodded.

“How? And where’d they get it?”

Roland didn’t know. What he did know was that the cave was a ma’sun—a war-chest. Below them, men were making war on the Tower which the line of Eld was sworn to protect. He and his tet would fall upon them by surprise, and with these tools they would smite and smite until their enemies lay with their boots pointed to the sky.

Or until theirs did.

“Maybe he explains on one of the tapes he left us,” Jake said. He had engaged the safety of his new Cobra automatic and tucked it away in the shoulder-bag with the remaining Orizas. Susannah had also helped herself to one of the Cobras, after twirling it around her finger a time or two, like Annie Oakley.

“Maybe he does,” she said, and gave Jake a smile. It had been a long time since Susannah had felt so physically well. Sonot-preg . Yet her mind was troubled. Or perhaps it was her spirit.

Eddie was holding up a piece of cloth that had been rolled into a tube and tied with three hanks of string. “That guy Ted said he was leaving us a map of the prison-camp. Bet this is it. Anyone ’sides me want a look?”

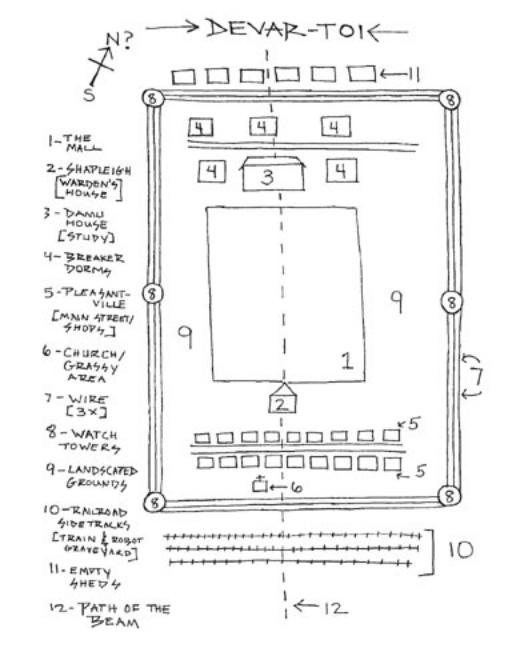

They all did. Jake helped Eddie to unroll the map. Brautigan had warned them it was rough,

and it surely was: really no more than a series of circles and squares. Susannah saw the name of the little town—Pleasantville—and thought again of Ray Bradbury. Jake was tickled by the crude compass, where the map-maker had added a question mark beside the letterN .

While they were studying this hastily rendered example of cartography, a long and wavering cry rose in the murk outside. Eddie, Susannah, and Jake looked around nervously.

Oy raised his head from his paws, gave a low, brief growl, then put his head back down again and appeared to go to sleep:Hell wit’choo, bad boy, I’m wit’ my homies and I ain’t

ascairt.

“What is it?” Eddie asked. “A coyote? A jackal?”

“Some kind of desert dog,” Roland agreed absently. He was squatted on his hunkers (which suggested his hip was better, at least temporarily) with his arms wrapped around his

shins. He never took his eyes from the crude circles and squares drawn on the cloth.

“Can-toi-tete.”

“Is that likeDan -Tete?” Jake asked.

Roland ignored him. He scooped up the map and left the cave with it, not looking back. The others shared a glance and then followed him, once more wrapping their blankets about them like shawls.

Three

Roland returned to where Sheemie (with a little help from his friends) had brought them through. This time the gunslinger used the binoculars, looking down at Blue Heaven long and long. Somewhere behind them, the desert dog howled again, a lonely sound in the gloom.

And, Jake thought, the gloom was gloomier now. Your eyes adjusted as the day dialed itself down, but that brilliant spotlight of sun seemed brighter than ever by contrast. He was

pretty sure the deal with the sun-machine was that you got your full-on, your full-off, and nothing in between. Maybe they even let it shine all night, but Jake doubted it. People’s nervous systems were set up for an orderly progression of dark and day, he’d learned that

in science class. You could make do with long periods of low light—people did it every year in the Arctic countries—but it could really mess with your head. Jake didn’t think the

guys in charge down there would want to goof up their Breakers if they could help it. Also, they’d want to save their “sun” for as long as they could; everything here was old and prone

to breakdowns.

At last Roland gave the binoculars to Susannah. “Do look ya especially at the buildings on either end of the grassy rectangle.” He unrolled the map like a character about to read a scroll in a stage-play, glanced at it briefly, and then said, “They’re numbered 2 and 3 on the map.”

Susannah studied them carefully. The one marked 2, the Warden’s House, was a small

Cape Cod painted electric blue with white trim. It was what her mother might have called a fairy-tale house, because of the bright colors and the gingerbread scalloping around the eaves.

Damli House was much bigger, and as she looked, she saw several people going in and out. Some had the carefree look of civilians. Others seemed much more—oh, call it watchful. And she saw two or three slumping along under loads of stuff. She handed the glasses to Eddie and asked him if those were Children of Roderick.

“I think so,” he said, “but I can’t be completely—”

“Never mind the Rods,” Roland said, “not now. What do you think of those two buildings, Susannah?”

“Well,” she said, proceeding carefully (she did not, in fact, have the slightest idea what it was he wanted from her), “they’re both beautifully maintained, especially compared to some of the falling-down wrecks we’ve seen on our travels. The one they call Damli House is especially handsome. It’s a style we call Queen Anne, and—”

“Are they of wood, do you think, or just made to look that way? I’m particularly interested in the one called Damli.”

Susannah redirected the binoculars there, then handed them to Eddie. He looked, then

handed them to Jake. While Jake was looking, there was an audibleCLICK! sound that rolled to them across the miles…and the Cecil B. DeMille sunbeam which had been

shining down on the Devar-Toi like a spotlight went out, leaving them in a thick purple dusk which would soon be complete and utter dark.

In it, the desert-dog began to howl again, raising the skin on Jake’s arms into gooseflesh. The sound rose…rose…and suddenly cut off with one final choked syllable. It sounded

like some final cry of surprise, and Jake had no doubt that the desert-dog was dead. Something had crept up behind it, and when the big overhead light went out—

There were still lights on down there, he saw: a double white row that might have been streetlights in “Pleasantville,” yellow circles that were probably arc-sodiums along the various paths of what Susannah was calling Breaker U…and spotlights running random

patterns across the dark.

No,Jake thought,not spotlights. Searchlights .Like in a prison movie. “Let’s go back,” he said. “There’s nothing to see anymore, and I don’t like it out here in the dark.”

Roland agreed. They followed him in single file, with Eddie carrying Susannah and Jake walking behind them with Oy at his heel. He kept expecting a second desert-dog to take up the cry of the first, but none did.

Four

“They were wood,” Jake said. He was sitting cross-legged beneath one of the gas lanterns, letting its welcome white glow shine down on his face.

“Wood,” Eddie agreed.

Susannah hesitated a moment, sensing it was a question of real importance and reviewing what she had seen. Then she also nodded. “Wood, I’m almost positive.Especially the one

they call Damli House. A Queen Anne built out of stone or brick and camouflaged to look like wood? It makes no sense.”

“If it fools wandering folk who’d burn it down,” Roland said, “it does. It does make sense.”

Susannah thought about it. He was right, of course, but—

“I still say wood.”

Roland nodded. “So do I.” He had found a large green bottle markedPERRIER . Now he opened it and ascertained that Perrier was water. He took five cups and poured a measure into each. He set them down in front of Jake, Susannah, Eddie, Oy, and himself.

“Do you call me dinh?” he asked Eddie.

“Yes, Roland, you know I do.”

“Will you share khef with me, and drink this water?”

“Yes, if you like.” Eddie had been smiling, but now he wasn’t. The feeling was back, and it was strong. Ka-shume, a rueful word he did not yet know.

“Drink, bondsman.”

Eddie didn’t exactly like being called bondsman, but he drank his water. Roland knelt before him and put a brief, dry kiss on Eddie’s lips. “I love you, Eddie,” he said, and

outside in the ruin that was Thunderclap, a desert wind arose, carrying gritty poisoned dust.

“Why…I love you, too,” Eddie said. It was surprised out of him. “What’s wrong? And don’t tell me nothing is, because I feel it.”

“Nothing’s wrong,” Roland said, smiling, but Jake had never heard the gunslinger sound so sad. It terrified him. “It’s only ka-shume, and it comes to every ka-tet that ever was…but now, while we are whole, we share our water. We share our khef. ’Tis a jolly thing to do.”

He looked at Susannah.

“Do you call me dinh?”

“Yes, Roland, I call you dinh.” She looked very pale, but perhaps it was only the white light from the gas lanterns.

“Will you share khef with me, and drink this water?”

“With pleasure,” said she, and took up the plastic cup.

“Drink, bondswoman.”

She drank, her grave dark eyes never leaving his. She thought of the voices she’d heard in her dream of the Oxford jail-cell: this one dead, that one dead, t’other one dead; O

Discordia, and the shadows grow deeper.

Roland kissed her mouth. “I love you, Susannah.”

“I love you, too.”

The gunslinger turned to Jake. “Do you call me dinh?”

“Yes,” Jake said. There was no question abouthis pallor; even his lips were ashy. “Ka-shume means death, doesn’t it? Which one of us will it be?”

“I know not,” Roland said, “and the shadow may yet lift from us, for the wheel’s still in

spin. Did you not feel ka-shume when you and Callahan went into the place of the vampires?”

“Yes.”

“Ka-shume for both?”

“Yes.”

“Yet here you are. Our ka-tet is strong, and has survived many dangers. It may survive this one, too.”

“But I feel—”

“Yes,” Roland said. His voice was kind, but that awful look was in his eyes. The look that was beyond mere sadness, the one that said this would be whatever it was, but the Tower

was beyond, the Dark Tower was beyond and it was there that he dwelt, heart and soul, ka and khef. “Yes, I feel it, too. So do we all. Which is why we take water, which is to say fellowship, one with the other. Will you share khef with me, and share this water?”

“Yes.”

“Drink, bondsman.”

Jake did. Then, before Roland could kiss him, he dropped the cup, flung his arms about the gunslinger’s neck, and whispered fiercely into his ear: “Roland, I love you.”

“I love you, too,” he said, and released him. Outside, the wind gusted again. Jake waited for something to howl—perhaps in triumph—but nothing did.

Smiling, Roland turned to the billy-bumbler.

“Oy of Mid-World, do you call me dinh?”

“Dinh!” Oy said.

“Will you share khef with me, and this water?”

“Khef! Wat’!”

“Drink, bondsman.”

Oy inserted his snout into his plastic cup—an act of some delicacy—and lapped until the water was gone. Then he looked up expectantly. There were beads of Perrier on his whiskers.

“Oy, I love you,” Roland said, and leaned his face within range of the bumbler’s sharp teeth. Oy licked his cheek a single time, then poked his snout back into the glass, hoping for a missed drop or two.

Roland put out his hands. Jake took one and Susannah the other. Soon they were all linked.Like drunks at the end of an A.A. meeting, Eddie thought.

“We are ka-tet,” Roland said. “We are one from many. We have shared our water as we have shared our lives and our quest. If one should fall, that one will not be lost, for we are one and will not forget, even in death.”

They held hands a moment longer. Roland was the first to let go.

“What’s your plan?” Susannah asked him. She didn’t call him sugar; never called him that or any other endearment ever again, so far as Jake was aware. “Will you tell us?”

Roland nodded toward the Wollensak tape recorder, still sitting on the barrel. “Perhaps we should listen to that first,” he said. “I do have a plan of sorts, but what Brautigan has to say might help with some of the details.”

Five

Night in Thunderclap is the very definition of darkness: no moon, no stars. Yet if we were

to stand outside the cave where Roland and his tet have just shared khef and will now listen to the tapes Ted Brautigan has left them, we’d see two red coals floating in that

wind-driven darkness. If we were to climb the path up the side of Steek-Tete toward those floating coals (a dangerous proposition in the dark), we’d eventually come upon a

seven-legged spider now crouched over the queerly deflated body of a mutie coyote. This can-toi-tete was a literally misbegotten thing in life, with the stub of a fifth leg jutting from its chest and a jellylike mass of flesh hanging down between its rear legs like a deformed udder, but its flesh nourishes Mordred, and its blood—taken in a series of long, steaming gulps—is as sweet as a dessert wine. There are, in truth, all sorts of things to eat over here. Mordred has no friends to lift him from place to place via the seven-league boots of teleportation, but he found his journey from Thunderclap Station to Steek-Tete far from arduous.

He has overheard enough to be sure of what his father is planning: a surprise attack on the facility below. They’re badly outnumbered, but Roland’s band of shooters is fiercely

devoted to him, and surprise is ever a powerful weapon.

And gunslingers are what Jake would callfou, crazy when their blood is up, and afraid of nothing. Such insanity is an even more powerful weapon.

Mordred was born with a fair amount of inbred knowledge, it seems. He knows, for

instance, that his Red Father, possessed of such information as Mordred now has, would have sent word of the gunslinger’s presence at once to the Devar-Toi’s Master or Security

Chief. And then, sometime later tonight, the ka-tet out of Mid-World would have

foundthemselves ambushed. Killed in their sleep, mayhap, thus allowing the Breakers to continue the King’s work. Mordred wasn’t born with a knowledge of that work, but he’s

capable of logic and his ears are sharp. He now understands what the gunslingers are about: they have come here to break the Breakers.

He could stop it, true, but Mordred feels no interest in his Red Father’s plans or ambitions. What he most truly enjoys, he’s discovering, is the bitter loneliness ofoutside . Of watching

with the cold interest of a child watching life and death and war and peace through the glass wall of the antfarm on his bureau.

Would he let yon ki’-dam actually kill his White Father? Oh, probably not. Mordred is

reserving that pleasure for himself, and he has his reasons; already he has his reasons. But as for the others—the young man, the shor’-leg woman, the kid—yes, if ki’-dam Prentiss

gets the upper hand, by all means let him kill any or all three of them. As for Mordred Deschain, he will let the game play out straight. He will watch. He will listen. He will hear

the screams and smell the burning and watch the blood soak into the ground. And then, if he judges that Roland won’t win his throw, he, Mordred, will step in. On behalf of the

Crimson King, if it seems like a good idea, but really on his own behalf, and for his own

reason, which is really quite simple:Mordred’s a-hungry.

And if Roland and his ka-tet should win their throw? Win and press on to the Tower?

Mordred doesn’t really think it will happen, for he is in his own strange way a member of their ka-tet, he shares their khef and feels what they do. He feels the impending break of their fellowship.

Ka-shume!Mordred thinks, smiling. There’s a single eye left in the desert-dog’s face. One of the hairy black spider-legs caresses it and then plucks it out. Mordred eats it like a grape,

then turns back to where the white light of the gas-lanterns spills around the corners of the blanket Roland has hung across the cave’s mouth.

Could he go down closer? Close enough to listen?

Mordred thinks he could, especially with the rising wind to mask the sound of his movements. An exciting idea.

He scutters down the rocky slope toward the errant sparks of light, toward the murmur of the voice from the tape recorder and the thoughts of those listening: his brothers, his sister-mother, the pet billy, and, of course, overseeing them all, Big White Ka-Daddy.

Mordred creeps as close as he dares and then crouches in the cold and windy dark, miserable and enjoying his misery, dreaming his outside dreams. Inside, beyond the blanket, is light. Let them have it, if they like; for now let there be light. Eventually he, Mordred, will put it out. And in the darkness, he will have his pleasure.

Chapter VIII:

Notes from

the Gingerbread House