матковська

.pdf

28 Cognitive Exploration of Language and Linguistics

2.2 From words to meanings: Semasiology

Let us suppose you want to communicate to someone else that you can see an apple. As already discussed in Chapter 1, you can make this clear in three di erent semiotic ways. You can point to it (indexical sign), you can draw a picture that resembles the thing (iconic sign), or you can say the word apple, which is a symbolic sign. In the last case, how does the word that I pronounce [æp6l] relate to the thing I see? The word itself is of course not the thing itself, but only a symbol for the thing. A symbolic sign is a given form which symbolizes or stands for a concept (or a meaning) and this concept is related to a whole category of entities in the conceptual and experiential world. The relationship between these three elements (a) form, b) concept or meaning, and c) referent or entity in the conceptual and experiential world) was presented in a triangle in Chapter 1, Table 2 and is reproduced here as Table 2 for the sake of clarity.

Table 2. The semiotic triangle

concept or meaning B

A |

SIGN |

C |

|

form |

referent, i.e., entity in |

|

conceptual and |

|

experienced world |

Although many di erent interpretations have been proposed for this semiotic triangle since it was devised by its inventors Ogden and Richards (1923), the interpretation proposed here is generally acceptable. There is a direct, though conventional link between A (form) and B (concept, meaning) and between B (concept) and C (referent, i.e., entity in conceptual and experienced world). But there is only an indirect link between A (form) and C (referent or entity in world), indicated by the interrupted line AC. This semiotic triangle is a further elaboration of the views of the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, who introduced two essential terms: The word form is the signifiant (that which signifies), and the meaning of the word is the signifié (that which is signified). We will refer to the former simply as word form or word and put it in italics, and to the latter as meaning — or if a word form is polysemous, as its senses — and put it in single quotation marks. For example, the word (form) apple stands for the meaning ‘a kind of fruit’.

Chapter 2. What’s in a word? 29

As the dictionary entry of the word fruit in Section 2.1 shows, this word has more than one meaning. Next to the basic, every-day sense ‘sweet and soft edible part of a plant’ as in (1a), illustrated in Figure 1a, it has various other senses. In its technical sense (1b) ‘the seed-bearing part of a plant or tree’, the word refers to things that are not usually included in its every-day use, as shown in Figure 1b. It also has a more general use in an expression like the fruits of nature (1d), which refers to ‘all the natural things that the earth produces’ (including, for instance, grains and vegetables). In addition to these literal senses, there is a range of figurative senses, including the abstract sense in (1c) ‘the result or outcome of an action’ as in the fruits of his labour or his work bore fruit, or the somewhat archaic senses in (1e) ‘homosexual’ or in (1f) ‘o spring, progeny’ as in the biblical expressions the fruit of the womb, the fruit of his loins.

Each of these di erent uses represents a separate sense of fruit. In turn, each sense may be thought of as referring to a di erent set of things in the outside world, a set of referents. For example, when we use the word fruit with the basic sense ‘sweet and soft edible part of a plant’, we refer to a set of referents that includes apples, oranges, bananas, and many other sweet and soft edible objects as in Figure 1a. If we use fruit in its second sense ‘seed-bearing part of plant’, we think of the fruit’s function as a seed for future plants, typically shown by the seeds or the referents in the middle of the melon in Figure 1b.

But the seed-bearing part may be the whole fruit as is the case with a walnut, which is “technically speaking” a fruit (in the second sense), but it is probably not a fruit in the every-day sense. Thus in the case of a walnut, the referent is the whole seed-bearing part. In the case of the melon (in the second, technical sense), the referent is rather the core with the seeds. However, in the every-day sense, it is rather the edible part. A referent can be defined in a

a. Cut oranges |

b. melon seeds |

Figure 1.

30 Cognitive Exploration of Language and Linguistics

simplified way as an entity or part of an entity evoked by words. Each word sense evokes a member of a di erent conceptual category. In the fruit example, the category members happen to be material objects, but in the case of verbs, they could be actions and in the case of adjectives, they could be properties.

There is no precondition that the “things” in the category need exist in the real world. The category “fruit” contains all real and imaginary apples and oranges that fruit could possibly be applied to, in the same way in which goblin will have a set of members associated with it, regardless of whether goblins are real or not.

In the next sections we will look more closely at the relationships among members of a category. We will look at which member is considered the most central or salient one (2.2.1), how the members are linked to each other in meaning (2.2.2), and how meanings are fuzzy, i.e. cannot always be distinguished clearly (2.2.3).

2.2.1 Salience: Prototypical word senses and referents

In Chapter 1.3.1, it was shown that categories, e.g. the category “chair”, have prototypical or central members and more marginal or peripheral members. This principle does not only apply to the members of a category, but also to the various senses of a word form. The question then is: How can we tell which sense of a word form like fruit is the most central? There are three interrelated ways that help us determine which sense of a word is the most central. In order to establish the salience of a sense, we can look at what particular sense comes to mind first, we can make a statistical count as to which use is the most frequent, or we can look at which sense is the more basic in its capacity to clarify the other senses.

When you hear someone say “I like fruit”, probably the first thing that comes to everybody’s mind, not only to the dictionary maker’s, is the ‘sweet and soft edible part’ sense and not the archaic ‘o spring’ sense. The technical sense of ‘seed-bearing part of a plant or tree’ would not occur to us as immediately, unless we were talking about fruit in that sort of context. If you were to count the types of senses where a word like fruit is used in every-day language, you would probably discover that the ‘edible part’ sense is used far more frequently than the other senses. From this we may infer that the sense ‘edible part’ is much more central or salient in our conception of fruit than the ‘seed-bearing part’ sense and certainly more salient than the archaic ‘o spring’ sense. Another reason for regarding both the ‘edible part’ and also the ‘seed-bearing part’ sense

Chapter 2. What’s in a word? 31

as more central than the other senses is the fact that these senses are a good starting-point for describing the other senses of fruit. For example, suppose you don’t know the expression fruit of the womb. This sense can be understood more easily through the central ‘seed-bearing part’ sense of fruit rather than the other way round. In other words, the most salient, basic senses are the centre of semantic cohesion in the category: They hold the category together by making the other senses accessible to our understanding.

Thus centrality e ects or prototypicality e ects mean that some elements in a category are far more conspicuous or salient, or more frequently used than others. Such prototypicality e ects occur not only at the level of senses but also at the level of referents. As we saw earlier, fruit has many di erent referents. When Northern Europeans are asked to name fruits, they are more likely to name apples and oranges than avocados or pomegranates whereas Southern Europeans would name figs. Also, if we were to count the actual uses of words in a Northern European context, references to apples or oranges are likely to be more frequent than references to mangoes.

2.2.2 Links between word senses: Radial networks

The fact that some word senses are more salient and others more peripheral is not the only e ect under consideration here. Word senses are also linked to one another in a systematic way through several cognitive processes so that they show an internally structured set of links. In order to analyze these links and the processes that bring them about, let us consider the senses of school in (3).

(3) school |

|

|

a. |

‘learning institution or building’ |

Is there a school nearby? |

b. |

‘lessons’ |

School begins at 9 a.m. |

c. |

‘pupils and/or sta of teachers’ |

The school is going to the British |

|

|

Museum tomorrow. |

|

|

We must hand in the geography |

|

|

project to the school in May. |

d. |

‘university faculty’ |

At 18 she went to law school. |

e. |

‘holiday course’ |

Where is the summer school on |

|

|

linguistics to be held? |

f. |

‘group of artists with similar |

Van Gogh belongs to the Im- |

|

style’ |

pressionist school. |

32 Cognitive Exploration of Language and Linguistics

g.‘views shared by a group of people’

h.‘a group of big fish swimming together’

There are two schools of thought on drinking red wine with fish. A school of whales followed the boat.

The first sense of school in (3a) is in fact not just ‘learning institution’, but it can also be the place or building where the learning institution is housed. Thus in the sentence She left school at the age of 14, the word school can only mean ‘learning institution’, but in She left the school after 4 p.m., school can mean both, and in The school was burned down only the building is meant.

The last case in (3h) is a problem. As stated before (see definition of homonymy) there are, historically speaking, two words school. The senses in (3a–g) of school go back to a Latin word schola; the last meaning (3h) is not an extension of the other senses but it stems from a di erent word form, i.e. Old English scolu ‘troup’ and has its own development. Still, in the present use of the meaning of school as ‘group of big fish’, the language user appeals to folk etymology and may rather see this meaning as a metaphorical extension of the other senses. Accordingly we will treat the ‘group of big fish’ sense of school as a process of folk etymology, taking all the senses of this word to be related to each other.

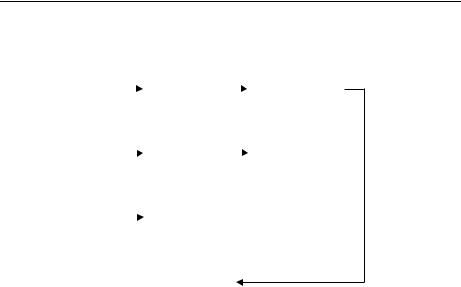

So, these eight senses appear to form a cluster that is structured in the shape of a radial network, i.e. a centre with radii going in various directions. For the radial network representing the senses of school we find four main directions as represented in Table 3.

What are now the processes that constitute the links within this radial network? It is clear that the central meaning of school has to do with ‘learning by a group of (young) people’. There are four di erent processes that allow us to focus on one or more components in this general category. The first is metonymy. In metonymy (from Greek meta ‘change’ and onoma ‘name’) the basic meaning of a word can be used for a part or the part for the whole. For instance, school as a ‘learning institution for a group of people’ allows us to focus upon each subset (the pupils, the sta ) of this complex category and we can take the subset (e.g. the head of the school) for the whole category. In metonymy the semantic link between two or more senses of a word is based on a relationship of contiguity, i.e. between the whole of something, i.e. school as an “institution for learning in group” and a part of it, e.g., the lessons. In fact, the expression the school can metonymically stand for each of its components, i.e. the building itself, the lessons, the pupils, the sta , the headmaster etc. More generally, contiguity is the state of being in some sort of contact such as that between a part and a whole, a container and the contents, a place and its inhabitants, etc.

Chapter 2. What’s in a word? 33

Table 3. Radial network of the senses of school

c. ‘pupils / teaching staff ’ |

|

h. ‘group of fish’ |

|

b. ‘lessons’

a. ‘learning institution; |

d. ‘university faculty |

building’ |

e. ‘one special course’’ |

f.‘group of artists sharing style’

g.‘group of people sharing opinions’

For example, in English and most languages we may say something like He drank the whole bottle. With such an expression we mean of course the contents in the bottle and not the bottle itself. Because the bottle and its contents are literally in contact with each other, this is considered a metonymic link. As we will see in Chapter 3.3, however, the concept of contiguity does not apply only to real physical or spatial contact, but also to more abstract associations such as time or cause.

The link which language users as folk etymologists make between the sense of school as a ‘group of pupils/teaching sta ’ and its most peripheral sense as ‘a group of fish swimming together’ is based on the process of metaphor. Metaphor (from Greek metapherein ‘carry over’) is based on perceived similarity. Referring to the bottom part of a mountain as the foot of the mountain is based on a conceived similarity between the structure of the human body and a mountain and hence a transfer is made from the set-up of the human body to that of the environment. Even the interpretation of a homonym such as school in the sense of ‘group of fish’ can be related to the senses of school as ‘group of pupils’ and may thus be motivated by the relation of similarity which language users perceive between a group of pupils following a master and a group of fish swimming together and following a leader. But the similarity is completely in the eyes of the beholder: If he wants to see the similarity, it is there. But the link is never objectively given as in the case of metonymy, where the relation of contiguity always involves some objective link between the various senses of a word. In metaphor one of the basic senses of a form, the source domain, e.g. elements of the human body, is used to grasp or explain a sense in a di erent domain, e.g. the elements of a mountain, called the target domain.

34 Cognitive Exploration of Language and Linguistics

The other senses of school are based on the processes of specialization and generalization. The process of specialization is found with the senses of school as in (3d) ‘a university faculty’ and (3e) ‘one special course’. In a process of specialization the word’s original meaning is always narrowed down to a smaller set of special referents. Thus from the general meaning of school as ‘an institution for learning’, English has narrowed the sense down to that of an ‘academic unit for learning’ (3d) and even further down to ‘any specialized institution for learning one specific subject’ as is usually the case in a summer school (3e), or a dance school, a language school, etc.

Another example of specialization is the English word corn, which was originally a cover-term for ‘all kinds of grain’. Later it specialized to the most typical referent in various English-speaking countries such as ‘wheat’ in England, ‘oats’ in Scotland, and ‘maize’ in the USA. The word queen also went through a specialization process. Originally, it meant any ‘wife or woman’, but now it is highly restricted to only one type of wife as in ‘king’s wife’ or ‘female sovereign’. Each language abounds with cases of specialization. Thus hound now denotes ‘a dog used in hunting’, but it used to denote ‘any kind of dog’, like the German or Dutch words Hund, hond ‘dog’. Similarly deer originally meant ‘any animal’ like German or Dutch Tier, dier ‘animal’, fowl meant ‘any kind of bird’ like German or Dutch Vogel ‘bird’, to starve meant ‘any form or way of dying’ like Dutch sterven, German sterben ‘to die’.

The opposite of specialization is generalization, which we find in the senses of school as in (3f) ‘group of artists’ or (3g) ‘group of people sharing opinions’. Here the meaning component of ‘an institution for learning’ has been broadened to that of ‘any group of people mentally engaged upon shared activities or sharing views of style or opinions’. Some other examples of generalization are moon and to arrive. The word moon originally referred to the earth’s satellite, but it is now applied to any planet’s satellite. The verb to arrive used to mean ‘to reach the river’s shore’ or ‘to come to the river bank’, but now it means ‘to reach any destination’.

In summary (see Table 4), the di erent senses of a polysemous word like school form a cluster of senses which are interrelated through di erent links: metonymy, metaphor, specialization and generalization. The various senses of a word are thus systematically linked to one another by means of di erent paths. Together, the relations between these senses form a radial set as shown in Table 3, starting from a central (set of) sense(s) and developing into the di erent directions. In addition, Table 4 o ers a survey of the possible processes that have led to the meaning extensions of school.

Chapter 2. What’s in a word? 35

Table 4. Processes of meaning extension of school

METONYMY

a. ‘learning |

|

|

|

b. lessons |

|

|

c. ‘pupils, |

||

|

|

|

|||||||

institution’ |

|

|

|

|

teaching staff ’ |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

SPECIALIZATION |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

d. ‘university, |

|

|

e. ‘special course’ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

faculty’ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

GENERALIZATION |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

f. ‘school of |

|

|

g. ‘school |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

artists’ |

|

|

of thought’ |

METAPHOR

h. ‘school of fish’

2.2.3 Fuzziness in conceptual categories and word senses

So far we have talked about the senses of a word as if they are clearly separate from each other. But we saw in Chapter 1 that meanings reflect conceptual categories. Categories may have clear centres, but their boundaries may not be clear-cut, and categories may overlap. As already discussed in Chapter 1.3.1, this phenomenon is called fuzziness, i.e. the boundaries of any category may be unclear or fuzzy. Since senses symbolize conceptual categories, it is no surprise that they cannot be defined in such a way that they include all the referents that should be included and exclude those that do not belong to the category. As an illustration, let us consider the question whether the central sense of fruit can be delimited in a straightforward fashion. Such a delimitation would take the form of a classical definition, a definition that lists all the necessary and su cient conditions for something to be a member of a category. Such a classical definition is possible for any mathematical category, e.g. the category of “triangle”, which is defined as ‘a flat shape with three straight sides and three angles’ (DCE). A condition is necessary in the sense of naming characteristics that are common to all triangles, and it is su cient in the sense that it distinguishes a category, e.g. a triangle from any other category, e.g. a shape like  . This shape has three lines, but only two angles. So both elements “three lines” and “three angles” are necessary conditions, but at the same time also su cient conditions: A flat shape with three lines and three angles can only be a triangle. But things are di erent with most natural categories.

. This shape has three lines, but only two angles. So both elements “three lines” and “three angles” are necessary conditions, but at the same time also su cient conditions: A flat shape with three lines and three angles can only be a triangle. But things are di erent with most natural categories.

36 Cognitive Exploration of Language and Linguistics

If we try to give the necessary conditions or characteristics for fruit, characteristics such as sweet, soft, and having seeds may come to mind as good candidates. But these are not always necessary since lemons are not sweet, avocados are not necessarily soft, and bananas do not contain parts that are immediately recognizable as seeds. There are of course a number of characteristics that are necessary. All fruits “grow above the ground on plants or trees” rather than in the ground. They have “to ripen” before you can eat them, and if you want to prepare them rather than eat them raw, you would primarily use sugar, or at least use them in dishes that have a predominantly “sweet taste”. Taken together, however, these obligatory features are not su cient since they do not exclude almonds and other nuts or a vegetable like rhubarb, which grows above the ground and is usually cooked with sugar.

We must conclude, then, that the central sense of fruit cannot be defined in a classical sense, satisfying both necessary and su cient conditions and covering all the eventualities of what speakers understand by fruit. However, this does not mean that our conceptualization of fruit, our mental picture of fruit, what we call to mind when we think of fruit, is necessarily fuzzy or illdefined. It could very well be that the image that spontaneously comes to mind when we think of fruit is very clear-cut. Indeed, when we ask people to name a few examples of fruit, they will come up with very much the same list. But all the same, we also have to accept that such a mental image does not fit all fruits equally well.

2.3 From concepts to words: Onomasiology

Whereas semasiological analysis starts with a word and tries to discover the various senses it may have, onomasiological analysis starts from a given concept and investigates the words that are used to name that particular concept. What is the purpose of onomasiological analysis? First of all, it can help us find out where (new) lexical items come from and which mechanisms are used to introduce di erent words for the same concept into the vocabulary of a language. The main purpose of onomasiological analysis is to discover patterns in a group of conceptually related words, called a lexical field. A lexical field is a collection of words that all name things in the same conceptual domain. Thus words such as breakfast, lunch and brunch are related and belong to the same lexical field because they all name things in the domain of “meals”. A conceptual domain, in its turn, can be defined as any coherent area of conceptualization,

Chapter 2. What’s in a word? 37

such as meals, space, smell, colour, articles of dress, the human body, the rules of football, etc., etc.

The question is: What is the position and status of single words in a lexical field delimited by a more general word like meal? Other typical examples of lexical fields are found in conceptual domains such as disease, travel, speed, games, knowledge, etc. As we will show in the next sections, the conceptual relations that occur between words in a lexical field are very analogous to those between the senses of a word identified in the section on semasiology: salience e ects, links and fuzziness.

2.3.1 Salience in conceptual domains: Basic level terms

Just as there are salience e ects in semasiology, which tell us which one of all the senses of a word or which one of the referents is thought of first and used most often, there are salience e ects in onomasiology. For example, in a group of words like animal, canine, and dog, the hierarchical order goes from more general to more specific. If faced with something that barks at you, probably a word like dog would come to mind first. This would be one type of salience e ect. Another type of salience e ect may occur in a group of words that are at the same level of a hierarchy, such as labrador, Alsatian, German shepherd, and so on. Some names for dog breeds may occur more often than others. Both types of salience e ects are discussed below.

According to anthropologist Brent Berlin, popular classifications of biological domains usually conform to a general organizational principle. Such classifications consist of at least three — for Berlin’s investigation even five — levels, which go from very broad or generic to very narrow or specific. Thus in conceptual domains (see Table 5) with several levels, the most general category is at the highest level, and the most specific one is at the lowest level. A basic level term is a word which, amongst several other possibilities, is used most readily to refer to a given phenomenon. There are many indications that basic level terms are more salient than others. For example, while learning a language, young children tend to acquire basic level terms such as tree, cow, horse, fish, skirt before generic names like plant, animal, garment, vehicle, fruit or specific names such as oak tree, labrador, jeans, sports car and Granny Smith. From a linguistic point of view, basic level terms are usually short and morphologically simple. From a conceptual point of view, the basic level constitutes the level where salience e ects are most outspoken. At the basic level category, individual members have the most in common with each other, and have the least in