Schuman S. - The IAF Handbook of Group Facilitation (2005)(en)

.pdf

board member and teacher 2 to form a subcommittee and draft a proposal. Their charge was to come up with a plan that met two objectives: (1) it would cover everyone’s concerns, and (2) it would be acceptable to all parties. Exhibit 8.2 shows what they came back with.

Exhibit 8.2

The Pseudo-Solution

Policies for Improving Discipline at Lincoln Junior High School

•Extreme student misbehavior will not be tolerated at this school.

•A quarterly newsletter, stressing the importance of discipline at home, shall be mailed to parents.

•Every teacher and administrator will be expected to read two books or articles on positive methods of child discipline during the next year.

•Teachers shall try harder to handle student misbehavior within their classrooms.

Adapted from Kaner, Lind, Toldi, Fisk, and Berger, 1996.

At Community At Work, we call this type of outcome a pseudo-solution: innocuous, noncontroversial, and entirely ineffectual. Yet when it was submitted to the other participants for their endorsement, it was almost adopted. The parent and the school principal made it known that they were willing to approve it. It was blocked only because one of the teachers held out, insisting that this proposal, if implemented, would have no effect on student discipline and would be regarded by the faculty with cynicism and scorn. The school principal then realized that the proposal had the potential to lower teacher morale and undermine the school’s

Promoting Mutual Understanding for Effective Collaboration |

119 |

credibility with the broader community. After a few more rounds of discussion, the group decided to hire a professional facilitator. Thus, a Community At Work facilitator became engaged in this case.

Enter the Facilitator

The facilitator began her work by interviewing each person separately. She did this for two equally important reasons: so she could spend quality time with each of them as individuals in order to begin building positive relationships with them and so she could begin to learn about each person’s subjective reality as it influenced his or her thinking about student discipline. In this regard, she was interested not only in their stakeholder positions but also anything else—background, core values, assumptions—that might be meaningfully related to the task at hand, in the mind of the person being interviewed.

Exhibit 8.3 shows a small sample of what she learned from the interviews regarding the participants’ frames of reference.

As the exhibit makes clear, each participant’s opinions on student discipline were shaped by his or her own life experience. This provides a perfect illustration of the classic problem of intersubjectivity. The problem is that everyone who participates in a given discussion interprets it quite differently. If those participants do not know each other well (and often, even when they do know each other well) their discussions will be laced with misinterpretations and misunderstandings— sometimes explicit and sometimes unnoticed.

The challenge for the student discipline policy-setting group, as for any other multistakeholder group that comes face to face with the problem of intersubjectivity, was this: What will it take for group members to transcend their individual frames of reference and build a shared framework of understanding.

DYNAMICS OF GROUP DECISION MAKING

To prepare the group to move toward effective collaboration based on mutual understanding, the facilitator began by teaching the group about the dynamics of group decision making. She wanted to give participants the ability to communicate objectively about the experiences they were having. This meant teaching them a few simple principles that would provide them with shared points of reference and shared language.

120 |

The IAF Handbook of Group Facilitation |

Exhibit 8.3

Frames of Reference

PARENT

•Last month, her son had to get stitches because he got caught in the middle of a playground fight.

•There have been two burglaries recently in her neighborhood.

•She grew up in a small town where they left their houses unlocked day and night.

TEACHER 1

•She is nearing retirement and doesn't want to stay up nights changing lesson plans that worked fine for years.

•The principal gave her a bad evaluation last year, and she‘s afraid she‘ll be put on a performance review.

TEACHER 2

•He has a master‘s degree in child psychology and has attended intensive summer training seminars about self- esteem-based behavior programs.

•He had a rough home life as a child and often misbehaved at school to get attention.

•He feels alienated from his peers, who often accuse him of taking the kids‘ side too often. He feels hurt by teachers

who hint that he needs kids to like him.

PRINCIPAL

•As her budget has been further cut each year, she has had to assume increasing responsibility for jobs that were previously done by resource teachers and an assistant principal.

•She constantly feels under the gun with deadline pressures and feels blamed from all sides. She wants people to help shoulder the responsibilities, but she doesn't know how to get them to help her.

SCHOOL BOARD MEMBER

•He went to grammar school in the 1940‘s. His teachers were strict disciplinarians.

•He served with distinction in the Korean War. Then he started his own business. He believes strongly in the value of selfreliance.

•He was elected to the school board on a campaign of fiscal responsibility, so he has not paid close attention to academic matters.

Adapted from Kaner, Lind, Toldi, Fisk, and Berger, 1996.

Promoting Mutual Understanding for Effective Collaboration |

121 |

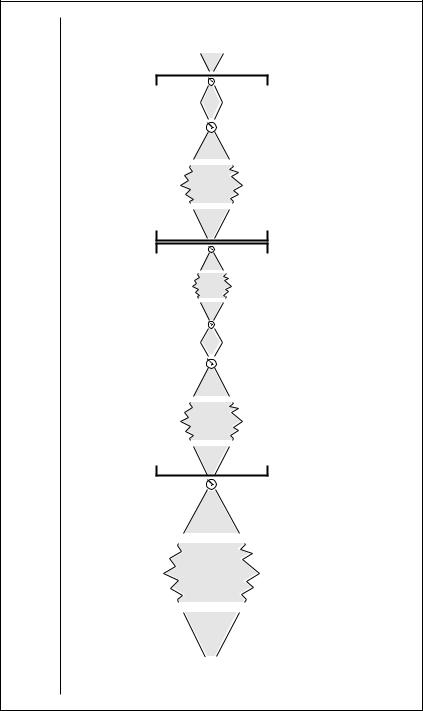

First, she explained the principles of divergent thinking and convergent thinking, and gave them examples of each type of process in action. “When a group is in a divergent phase,” she explained, “the members are tossing out their thoughts and beliefs without even trying to understand one another. People are just ‘putting it out there.’ In a convergent phase, in contrast, people are more naturally focusing, narrowing, simplifying—coming together as they move toward agreement.” (See Exhibit 8.4.)

Exhibit 8.4

Divergent and Convergent Thinking

|

|

|

|

|

g |

|

|

|

|

in |

|

|

|

|

k |

|

|

|

|

|

in |

|

|

|

|

|

Th |

|

|

|

|

|

nt |

|

|

|

|

e |

|

|

|

|

g |

|

|

|

|

|

r |

|

|

|

|

e |

|

|

|

|

|

iv |

|

|

|

|

|

D |

|

|

|

|

|

New

Topic

Convergent Think

ing

Decision

Point

Divergent Thinking |

|

Convergent Thinking |

Generating alternatives |

vs. |

Evaluating alternatives |

Free-for-all open discussion |

vs. |

Summarizing key points |

Gathering diverse points of view |

vs. |

Sorting ideas into categories |

Unpacking the logic of a problem |

vs. |

Arriving at a general conclusion |

Adapted from Kaner, Lind, Toldi, Fisk, and Berger, 1996.

122 |

The IAF Handbook of Group Facilitation |

Then she introduced the key problem, intersubjectivity (though she never used that term). To her audience of participants, she posed the problem as “the struggle to understand one another, the struggle to integrate each other’s points of view.” Thus, the facilitator proceeded to show the group how difficult it is for people in any group to put their own opinions aside while they focus on one another’s perspectives. To help group members see this, she led them through a three-step activity. First, she asked them to generate but not discuss some examples from their own interactions with one another. Second, they generated a related list using examples from previous experiences in different groups entirely. Third, they discussed

the new thoughts and insights that were now surfacing.

In the ensuing discussion, the facilitator validated the obvious: in the throes of misunderstandings and under time pressure, group members can be impatient, repetitious, insensitive, defensive, short-tempered, or worse. Building mutual understanding is a frustrating process. It can be draining and confusing. Still, it’s not a bad thing to go through that struggle; it’s perfectly normal. In fact, it’s actually a healthy thing—much healthier, indeed, than cranking out an ineffectual pseudosolution and calling it quits as a group.

At Community At Work, we have given this difficult period of group process a name: the Groan Zone (Kaner, Lind, Toldi, Fisk, and Berger, 1996). The goal of hanging in there and working through the Groan Zone is to achieve a shared framework of understanding, an ability to think from one another’s points of view. This capacity to think from the perspectives of other members is essential for developing an inclusive win/win solution.

The entire model, which was developed by several colleagues at Community At Work, is presented in Exhibit 8.5.

When the facilitator explained the dynamics of group decision making to the members of this group, they responded with a huge outpouring of relief. They said things like, “So you mean we’re normal?” and “I am so glad there are words to describe what I’ve been feeling.”

Yet despite the fact that their new insights strengthened their determination to persevere, it did not (and could not) prevent them from getting stuck in their own Groan Zones.

Promoting Mutual Understanding for Effective Collaboration |

123 |

Exhibit 8.5

Diamond of Participatory Decision Making

|

Business |

|

|

Usual |

|

|

as |

Divergent |

New |

? |

|

Topic |

|

Zone |

Time

|

|

Closure |

Groan |

Convergent |

Zone |

|

||

Zone |

Zone |

|

Decision

Point

This is the Diamond of Participatory Decision Making. It was developed by Sam Kaner with Lenny Lind, Catherine Toldi, Sarah Fisk, and Duane Berger. Facilitators can use this model in many ways: as a diagnostic tool, a road map, or a teaching tool to provide their groups with shared language and shared points of reference. But fundamentally it was created to validate and legitimize the hidden aspects of everyday life in groups.

Most people have trouble communicating in groups, especially when the issues are complex. But how often is this acknowledged? Blaming and complaining are more typical. This is self-defeating. Group dynamics can be awkward, but they are natural and normal nonetheless. Only when this is accepted can people succeed in tapping the enormous power of group decision making. These beliefs are at the very heart of Community At Work's philosophy of group facilitation.

Source: The Diamond of Participatory Decision-Making was originally published in S. Kaner, with L. Lind, C. Toldi, S. Fisk, and D. Berger, Facilitators’ Guide to Participatory Decision-Making, Gabriola Island B.C., Canada: New Society, 1996.

A TYPICAL GROUP DISCUSSION IN THE GROAN ZONE

Exhibit 8.6 is an illustration of “no listening.” Each person has spoken, but only superficially on the same topic. When “no listening” occurs, the group has no chance to build a shared framework. People are instead operating from their own points of view, disconnected from one another, driven for the most part by preexisting, fixed positions.

124 |

The IAF Handbook of Group Facilitation |

Exhibit 8.6

“No Listening” in the Groan Zone

TEACHER 1 |

TEACHER 2 |

“Perhaps your son |

“I'm sorry you had to deal with the |

needs professional |

break-in. But suspending our |

help. We are teachers, |

students for misbehavior will not |

not psychiatrists.“ |

change what happened to your son.“ |

PARENT

“Our house was broken into last year–my son still has nightmares.“

PRINCIPAL

“Sounds like you want to hold the school responsible for the conditions in your neighborhood.“

SCHOOL BOARD MEMBER

“I think we are all responsible for the safety of our neighborhoods. It's terrible that your son is still having nightmares. If we spent less tax money on our bloated school bureaucracy, we'd have more to spend on police, and people‘s homes would be better protected.“

Adapted from Kaner, Lind, Toldi, Fisk, and Berger, 1996.

Yet at the same time, these participants were beginning, bit by bit, to reveal their individual contexts. For the facilitator, the challenge was to tease out these personal frames of reference and, by using careful, effective listening skills, help the group members begin to listen better too. A facilitator’s skill at listening can have an enormous effect on participants’ capacity for transcending their fixed positions.

Promoting Mutual Understanding for Effective Collaboration |

125 |

BUILDING MUTUAL UNDERSTANDING THROUGH EFFECTIVE LISTENING

Mutual understanding requires taking the time to understand. This means taking time to listen. To ask. To wonder. To draw someone out. To show support and empathize.

All of these activities could conceivably be done by the members themselves, without the aid of a facilitator. Yet so often, it seems as though the facilitator is the only person in the room who is willing and ready to make the attempt to understand.

Why is this so? The obvious answer is that a facilitator is a trained listener who has been authorized to bring those skills to the group. But the question remains: Why only the facilitator? Why don’t the other members of a group use their own skills and talents to draw each other out and enhance mutual understanding?

Part of the answer resides in one’s capacity to tolerate discomfort and stay detached. A facilitator who can tolerate the discomfort of the Groan Zone will be able to keep listening, keep inquiring, keep trying to learn more about what really matters to each participant. Conversely, facilitators who feel uncomfortable and impatient will find themselves pushing their groups, not flowing with them. Under those circumstances, a group may arrive at the Convergent Zone, but the resulting agreements will likely be shaped by compromise and acquiescence, rather than by both/and thinking, in the service of a commitment to find inclusive solutions.

This, of course, does not relieve the facilitator of the duty to transfer the responsibility for effective listening to the group members. The more that participants listen to one another actively rather than through the mediating presence of a facilitator, the more quickly and capably they will grasp each other’s views.

In Exhibit 8.7 the behavior of effective listening is being done by the facilitator. This representation was deliberate, and it accurately reflects what was done by the real facilitator in the actual case, during periods when no one else was willing to pay more than superficial attention to the views and feelings of the others.

126 |

The IAF Handbook of Group Facilitation |

Exhibit 8.7

Effective Listening

“How can you expect my child to learn anything in a classroom with kids who are out of control?“

“Yes, it is–and I‘m worried for him. Our house was broken into last year, and he still has nightmares.“

“Yes, definitely. And I know it‘s not just about the schools. I worry about

him walking around our neighborhood“ I worry about his choice of friends. Raising a child in today‘s world is so frightening. As a mother, I feel overwhelmed.“

“I can see your child‘s education is important to you.“

“So is your son‘s personal safety part of your concern?“

PARENT |

FACILITATOR |

Adapted from Kaner, Lind, Toldi, Fisk, and Berger, 1996.

Later, as the case unfolded, and with consistent modeling by the facilitator, the group members became increasingly able to listen and therefore to understand and then to collaborate. They broke free of their pattern of making speeches, complaints, and veiled accusations (Exhibit 8.8).

Promoting Mutual Understanding for Effective Collaboration |

127 |

The Diamond Necklace

Exhibit 8.8

In a participatory decision-making process, a group should expect to reenter the Groan Zone again and again, whenever it becomes necessary to build shared understanding about a subissue that needs resolution. For example, objectives may need to be clarified. Agreements may be needed on items like scope, definitions of key terms, nonnegotiables, problem identification, solution criteria, and so forth — plus all the procedural issues like membership, schedules, meeting logistics, expenditures — you name it!

Following meeting

Next meeting

|

ageneral |

|

|

actionplans. |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Intheactualcasestudy,thegroupmadeitsmajorleapforwardwhenparticipantsagreedon |

framework,consistingofthesethreekeyelements: |

•Theremustbeconsequencesforstudentmisbehavior. •Teachersmusthaveordevelopeffectivebehaviormanagementskills. •Moreparentinvolvementinschoolactivitiesisneeded. |

Withinthisgeneralframework,thegroupproceededtoconvergeonspecificapproachesand |

Toldi,Fisk,andBerger,1996. |

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

AdaptedfromKaner,Lind, |

128 |

The IAF Handbook of Group Facilitation |