Color Atlas of Neurology

.pdf

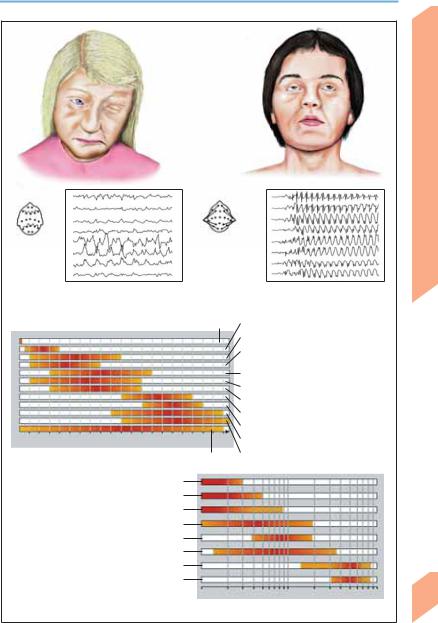

Epilepsy: Seizure Types

Ictal EEG: Focal activity on

left (frontoprecentral spike Clonus on right side waves)

of face

Clonus in right arm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

50 V |

|

|

|

|

Simple partial seizure |

|

|

|

1s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ictal EEG: Bilateral frontotemporal activity Oral automatisms (rhythmic ε waves)

(licking, chewing, lip smacking)

Oral automatisms |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(snorting, throat |

|

|

|

50 V |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

clearing, chewing) |

|

|

|

|

1s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

Complex partial seizure |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Partial seizures (focal epilepsy) |

|

|

|

|

||

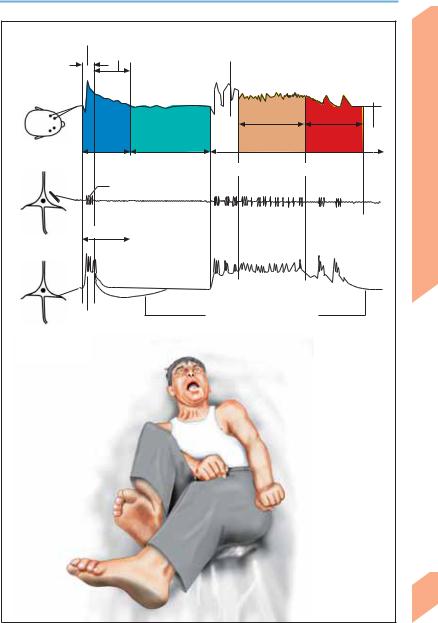

Interictal |

Prodromal |

Tonic |

Clonic |

|

Postictal phase |

|||

phase |

phase |

phase |

phase |

|

|

|

|

|

Normal EEG |

Focal or |

Ictal ` and _ |

Rhythmic |

Extinction |

Irregular and |

|

generalized |

spike waves |

slowing with |

phase |

high β and |

|

dysrhythmia |

|

occasional |

|

sub-β wave |

|

and slowing |

|

spikes |

|

activity |

Generalized seizures (schematic representation of ictal EEG in grand mal seizure)

Central Nervous System

193

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Central Nervous System

Epilepsy: Seizure Types

Site of focus |

Seizure type |

Symptoms and signs |

|

|

|

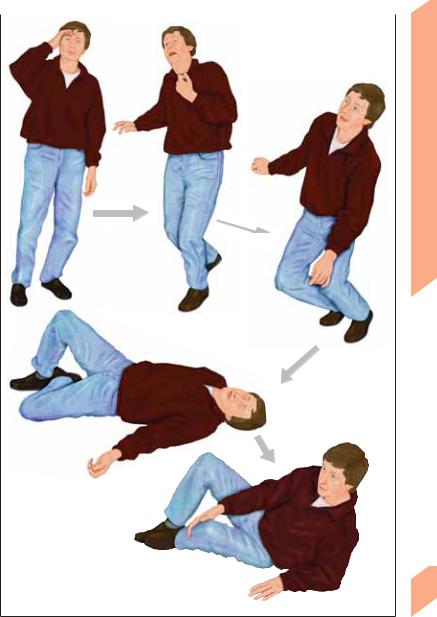

Frontal lobe |

Simple or complex par- |

|

tial seizures with or |

|

without secondary |

|

generalization (hypermo- |

|

tor frontal lobe seizures) |

Adversive head movement and other complex motor phenomena (mainly in legs), e. g., pelvic movements, ambulatory automatisms, swimming movements, fencing posture, staring, laughing, outcries, genital fumbling, autonomic dysfunction, speech arrest. Mood changes may also occur. Seizures occur several times a day with an abrupt onset. The unvarying course of the seizures may suggest hysteria. Brief postictal confusion

Temporal lobe |

Complex partial seizures |

Ascending epigastric sensations (nausea, heat sensa- |

|

with or without second- |

tion); olfactory/gustatory hallucinations; compulsive |

|

ary generalization |

thoughts, feeling of detachment, déjà-vu, jamais-vu; |

|

|

oral and other automatisms (psychomotor attacks); |

|

|

dyspnea, urinary urgency, palpitations; macropsia, |

|

|

micropsia; postictal confusion |

Parietal lobe |

Simple partial seizures |

Sensory and/or motor phenomena (jacksonian |

|

with or without second- |

seizures); pain (rare) |

|

ary generalization |

|

Occipital lobe |

Simple partial seizure |

|

with or without second- |

|

ary generalization |

(Adapted from Gram, 1990) |

|

! Generalized Seizures

Generalized epilepsy reflects paroxysmal discharges occurring in both hemispheres. The seizures may be either convulsive (e. g., general-

Unformed visual hallucinations (sparks, flashes)

ized tonic-clonic seizure GTCS) or nonconvulsive (myoclonic, tonic, or atonic seizures; absence seizures). Generalized seizures are classified by their clinical features.

|

Feature |

Absence Seizure |

Myoclonic |

Atonic |

Tonic-clonic Seizure |

|

|

|

Seizure |

(Astatic) |

|

|

|

|

|

Seizure |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conscious- |

Impaired |

Unaffected |

Impaired |

Impaired |

|

ness |

|

|

|

|

|

Duration |

A few (!30) seconds |

1–5 seconds |

A few sec- |

1–3 minutes |

|

|

|

|

onds |

|

|

Symptoms |

Brief absence, vacant |

Sudden, bi- |

Sudden loss |

Initial cry (occasionally); falls |

|

and signs |

gaze and blinking fol- |

laterally syn- |

of muscle |

(loss of muscle tone); respira- |

|

|

lowed by immediate |

chronous |

tone causing |

tory arrest; cyanosis; tonic, |

|

|

return of mental clar- |

jerks in arms |

severe falls |

then clonic seizures; muscle re- |

|

|

ity; automatisms (lip |

and legs; |

|

laxation followed by deep |

|

|

smacking, chewing, |

often occur in |

|

sleep. Tongue biting, urinary |

|

|

fiddling, fumbling) |

series |

|

and fecal incontinence |

|

|

may occur |

|

|

|

|

Age group |

Children and adoles- |

Children and |

Infants and |

Any age |

|

|

cents |

adolescents |

children |

|

|

Ictal EEG |

Bilateral regular |

Polyspike |

Polyspike |

Often obscured by muscle arti- |

|

|

3 (2–4) Hz spike |

waves, spike |

waves, flat- |

facts |

194 |

|

waves |

waves, or |

tening or low- |

|

|

|

sharp and |

voltage fast |

|

|

|

|

|

slow waves |

activity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(Adapted from Gram, 1990)

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Epilepsy: Seizure Types

Fixed stare, blank facial expression

|

100 V |

1s |

|

|

|

|

|

Generalized 3 Hz |

|

|

|

|

|

spike-wave activity |

Absence

Tonic arm Eyes open, upward gaze position

Mouth open

Leg extension

|

|

|

|

|

|

100 V |

1s |

Generalized |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

sharp/slow-wave |

|

|

|

|

|

activity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tonic seizure |

(in myoclonic/astatic epilepsy)

Body rigid, limbs extended, head back, grimace

Generalized tonic-clonic seizure

(Grand mal, tonic phase; transition to clonic phase with forceful, rhythmic convulsions)

EEG

EMG (masseter m.)

EMG (biceps brachii m.)

Pupillary diameter

Intravesical pressure

Blood pressure (systolic)

Heart rate

Respiratory rate |

|

|

|

Prodromal phase |

Ictal phase |

Extinction |

Recovery phase |

|

(tonic-clonic) |

phase |

|

Tonic-clonic grand mal seizure (temporal course)

Central Nervous System

195

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Central Nervous System

Epilepsy: Classification

The etiology and prognosis of epilepsy depend on its clinical type. All forms of epilepsy (e. g., absence epilepsy of childhood, juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, temporal lobe epilepsy, frontal lobe epilepsy, reflex epilepsy) are characterized by recurrent paroxysmal attacks; thus classification cannot be based on a single seizure. Epileptic syndromes vary in seizure pattern, cause, age at onset, precipitating factors, EEG changes, and prognosis (e. g., neonatal convulsions, infantile spasms and salaam seizures = West syndrome, Lennox–Gastaut syndrome, temporal lobe seizures). Seizures triggered by fever, substance abuse, alcohol, eclampsia, trauma, tumor, sleep deprivation, or medications are designated as isolated nonrecurring seizures or acute epileptic

reactions. Status epilepticus is a single prolonged seizure or a series of seizures without full recovery in between. Any type of seizure (convulsive or nonconvulsive) may appear under the guise of status epilepticus. In grand mal status epilepticus, patients do not regain consciousness between seizures.

Location-related (focal, partial) epilepsy can be differentiated from generalized epilepsies and epileptic syndromes on the basis of the seizure pattern. Seizures that cannot be classified because of inadequate data on focal or generalized seizure development are called unclassified epilepsy or epileptic syndrome. Other terms used in classification refer to seizure etiology (e. g., idiopathic, cryptogenic, symptomatic).

Type of Epilepsy |

Features |

|

|

Location-related |

Partial (focal) seizures |

Generalized |

Generalized convulsive seizures (GCS) |

Idiopathic |

No known cause other than genetic predisposition. No manifestations |

|

other than epileptic seizures. Characteristic age of onset |

Cryptogenic |

Assumed to reflect a CNS disorder of unidentified type. (Once the cause |

|

is identified, epilepsy is classified as symptomatic.) |

Symptomatic |

Due to an identified CNS disorder or lesion |

|

|

|

Type of Epilepsy |

Etiology |

Epilepsy/Epileptic Syndrome |

|

Location-related |

Idiopathic (charac- |

Benign epilepsy of childhood with centrotemporal spikes; |

|

(focal, localized, |

teristic age of |

epilepsy of childhood with occipital paroxysms |

|

partial) |

onset) |

|

|

|

Cryptogenic or |

Variable expression depending on cause and location (e. g., tem- |

|

|

symptomatic |

poral, frontal, parietal, or occipital lobe epilepsy) |

|

Generalized |

Idiopathic (charac- |

Absence epilepsy of childhood (pyknolepsy); juvenile absence |

|

|

teristic age of |

epilepsy; juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (impulsive petit mal); awak- |

|

|

onset) |

ening grand mal epilepsy (GTCS); epilepsy with specific triggers |

|

|

|

(reflex epilepsy) |

|

|

Cryptogenic or |

West syndrome (infantile spasms, salaam seizures); Lennox– |

|

|

symptomatic |

Gastaut syndrome; myoclonic-astatic epilepsy; epilepsy with |

|

|

|

myoclonic absence |

|

|

Symptomatic |

Early myoclonic encephalopathy (unspecific etiology); seizures |

|

|

|

secondary to various diseases |

|

Unsure whether |

Idiopathic or symp- |

Neonatal convulsions; acquired epileptic aphasia (Landau– |

|

focal or general- |

tomatic |

Kleffner syndrome) |

|

ized |

|

|

196 |

Variably focal and |

Symptomatic |

Febrile convulsions; isolated seizure or isolated status epilepti- |

|

generalized |

(situation-related |

cus; acute metabolic or toxic triggers |

seizure)

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.