Color Atlas of Neurology

.pdf

CNS Infections

Replication in

tonsils |

|

Oral transmission |

|

of poliovirus |

Motor neuron |

Viremia

Neuronal involvement (organ manifestation)

Route of infection

Paresis and muscular atrophy

|

Neurogenic |

Acute poliomyelitis |

muscle lesion |

Incomplete recovery (muscular atrophy)

Latency phase (10-15 years) with stable deficit

Complete recovery (no muscular atrophy)

Postpolio syndrome

Increasing muscular atrophy |

New muscular atrophy |

Central Nervous System

243

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

CNS Infections

! Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy

|

(PML) |

|

|

Pathogenesis. The causative organism, JC virus, |

|

|

is a ubiquitous papovavirus that usually stays |

|

|

dormant within the body. It is reactivated in |

|

|

persons with impaired cellular immunity and |

|

|

spreads through the bloodstream to the CNS, |

|

|

where it induces multiple white-matter lesions. |

|

|

Symptoms and signs. PML appears as a compli- |

|

|

cation of cancer (chronic lymphatic leukemia, |

|

System |

Hodgkin lymphoma), tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, |

|

immune suppression, and AIDS, producing vari- |

||

able symptoms and signs. The major manifesta- |

||

|

||

|

tions in patients without AIDS are visual distur- |

|

Nervous |

bances (visual field defects, cortical blindness), |

|

hemiparesis, and neuropsychological distur- |

||

bances (impairment of memory and cognitive |

||

functions, dysphasia, behavioral abnormalities). |

||

Central |

The major manifestations of PML as a complica- |

|

tion of AIDS are (from most to least frequent): |

||

|

||

|

central paresis, cognitive impairment, visual |

|

|

disturbances, gait impairment, ataxia, dys- |

|

|

arthria, dysphasia, and headache. PML usually |

|

|

progresses rapidly, causing death in 4–6 |

|

|

months. The definitive diagnosis is by histologi- |

|

|

cal examination of brain tissue obtained by bi- |

|

|

opsy or necropsy. CT reveals asymmetrically dis- |

|

|

tributed, hypodense white-matter lesions |

|

|

without mass effect or contrast enhancement; |

|

|

these lesions are hyperintense on T2-weighted |

|

|

MRI, which also demonstrates involvement of |

|

|

the subcortical white matter (“U fibers”). The |

|

|

CSF findings are usually normal, but oligoclonal |

|

|

bands may be found in AIDS patients. |

|

|

Virustatic therapy. There is as yet no validated |

|

|

treatment regimen. |

|

|

! Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Infection |

|

|

Pathogenesis. CMV, a member of the her- |

|

|

pesvirus family, is transmitted through respira- |

|

|

tory droplets, sexual intercourse, and contact |

|

|

with contaminated blood, blood products, or |

|

|

transplanted organs. It is widely distributed |

|

|

throughout the world, with a regional and age- |

|

|

dependent prevalence of up to 100%. CMV vir- |

|

|

ions are thought to replicate initially in |

|

|

oropharyngeal epithelial cells (salivary glands) |

244and then disseminate to the organs of the body, including the nervous system, through the

bloodstream. The virus remains dormant in

monocytes and lymphocytes as long as the immune system keeps it in check. Reactivation of the virus is almost always asymptomatic in healthy individuals, but severe generalized disease can develop in persons with immune compromise due to AIDS, organ transplantation, immunosuppressant drugs, or a primary malignancy.

Symptoms and signs. The primary infection is usually clinically silent. Intrauterine fetal infection leads to generalized fetopathies in fewer than 5% of neonates. In immunocompromised patients, particularly those with AIDS, (reactivated) CMV infection presents a variable combination of manifestations, including retinitis (partial or total loss of vision), pneumonia, and enteritis (colitis, esophagitis, proctitis). The neurological manifestations of CMV infection are manifold. PNS involvement is reflected as Guil- lain–Barré syndrome or lumbosacral polyradiculopathy (subacute paraparesis with or without back pain or radicular pain). CNS involvement produces encephalitis, meningitis, ventriculitis (inflammatory changes in the ependyma) and/or myelitis. Symptoms and signs may be absent, minor, or progressively severe, as in HIV-related encephalopathy. CMV vasculitis may lead to ischemic stroke. The diagnosis usually cannot be made from the clinical findings alone (except in the case of CMV retinitis). MRI reveals periventricular contrast enhancement in CMV vasculitis; other MRI and CT findings are nonspecific. There may be CSF pleocytosis with an elevated protein concentration. The diagnosis can be established by culture or identification by polymerase chain reaction of CMV in tissue, CSF, or urine, or by serological detection of CMV-specific antibodies.

Virustatic therapy. Gancyclovir, foscarnet, or cidofovir are given for initial treatment and secondary prophylaxis.

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

CNS Infections

Foci of demyelination seen on MRI (no mass effect or contrast enhancement)

Dysarthria, dysphasia, cognitive impairment, behavioral changes

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

Cotton-wool spots near optic disk

Microangiopathy Hemorrhage

CMV retinitis

CMV ventriculitis on MRI (ependymal contrast enhancement)

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection

Central Nervous System

245

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

CNS Infections

|

! Rabies |

|

|

Pathogenesis. Rabies virus is a rhabdovirus that |

|

|

is mainly transmitted by the bite of a rabid ani- |

|

|

mal. The reservoirs of infection are wild animals |

|

|

in Europe and America (foxes, wild boar, deer, |

|

|

martens, raccoons, badgers, bats; sylvatic rabies) |

|

|

and dogs in Asia (urban rabies). The virus repli- |

|

|

cates in muscles cells near the site of entry and |

|

|

then spreads via muscle spindles and motor end |

|

|

plates to the peripheral nerves, as far as the spi- |

|

System |

nal ganglia and spinal motor neurons, where |

|

secondary replication takes place. It sub- |

||

sequently spreads to the CNS and other organs |

||

|

||

|

(salivary glands, cornea, kidneys, lungs) by way |

|

Nervous |

of the fiber pathways of the autonomic nervous |

|

months (range: 1 week to 1 year). Proof that the |

||

|

system. The limbic system (p. 144) is usually |

|

|

also involved. The mean incubation time is 2–3 |

|

Central |

biting animal was rabid is essential for diagno- |

|

sis, as rabies is otherwise very difficult to diag- |

||

|

||

|

nose until its late clinical manifestations appear. |

|

|

The virus can be isolated from the patient’s |

|

|

sputum, urine or CSF in the first week after in- |

|

|

fection. |

|

|

Symptoms and signs. The course of rabies can be |

|

|

divided into three stages. The prodromal stage |

|

|

(2–4 days) is characterized by paresthesia, hy- |

|

|

peresthesia, and pain at the site of the bite and |

|

|

the entire ipsilateral side of the body. The |

|

|

patient suffers from nausea, malaise, fever, and |

|

|

headache and, within a few days, also from |

|

|

anxiety, irritability, insomnia, motor hyperactiv- |

|

|

ity, and depression. |

|

|

Hyperexcitability stage. In the ensuing days, the |

|

|

patient typically develops increasing restless- |

|

|

ness, incoherent speech, and painful spasms of |

|

|

the limbs and muscles of deglutition, reflecting |

|

|

involvement of the midbrain tegmentum. Hy- |

|

|

drophobia, as this stage of the disease is called, is |

|

|

characterized by painful laryngospasms, respi- |

|

|

ratory muscle spasms, and opisthotonus, with |

|

|

tonic-clonic spasms throughout the body that |

|

|

are initially triggered by attempts to drink but |

|

|

later even by the mere sight of water, unex- |

|

|

pected noises, breezes, or bright light. There |

|

|

may be alternating periods of extreme agitation |

|

|

(screaming, spitting, and/or scratching fits) and |

246relative calm. The patient dies within a few days if untreated, or else progresses to the next stage

after a brief clinical improvement.

Paralytic stage (paralytic rabies). The patient’s mood and hydrophobic manifestations improve, but spinal involvement produces an ascending flaccid paralysis with myalgia and fasciculations. Weakness may appear in all limbs at once, or else in an initially asymmetrical pattern, beginning in the bitten limb and then spreading. In some cases, the clinical picture is dominated by cranial nerve palsies (oculomotor disturbances, dysphagia, drooling, dysarthrophonia) and autonomic dysfunction (cardiac arrhythmia, pulmonary edema, diabetes insipidus, hyperhidrosis).

Rabies prophylaxis. Preexposure prophylaxis:

Vaccination of persons at risk (veterinarians, laboratory personnel, travelers to endemic areas).

Local wound treatment: Thorough washing of the bite wound with soap and water.

Postexposure prophylaxis: Vaccination and rabies immunoglobulin.

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

CNS Infections

Rabies virus |

Sympathetic |

(bullet-shaped) |

trunk |

Motor end plate

Route of rabies virus transmission

Animal bite |

|

Excitation stage (hydrophobia) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Excitation stage (spasms, opisthotonus)

Central Nervous System

247

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Central Nervous System

248

CNS Infections

Opportunistic Fungal Infections

CNS mycosis is sometimes found in otherwise healthy persons but mainly occurs as a component of an opportunistic systemic mycosis in persons with immune compromise due to AIDS, organ transplantation, severe burns, malignant diseases, diabetes mellitus, connective tissue diseases, chemotherapy, or chronic corticosteroid therapy. Certain types of mycosis (blastomycosis, coccidioidmycosis, histoplasmosis) are endemic to certain regions of the world (North America, South America, Africa).

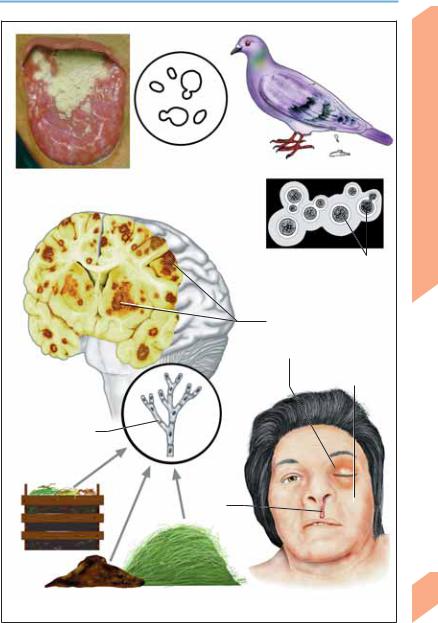

! Cryptococcus neoformans (Cryptococcosis)

Cryptococcus, a yeastlike fungus with a polysaccharide capsule, is a common cause of CNS mycosis. It is mainly transmitted by inhalation of dust contaminated with the feces of pet birds and pigeons. Local pulmonary infection is followed by hematogenous spread to the CNS. In the presence of a competent immune system (particularly cell-mediated immunity), the pulmonary infection usually remains asymptomatic and self-limited. Immune-compromised persons, however, may develop meningoencephalitis with or without prior signs of pulmonary cryptococcosis. Its manifestations are heterogeneous and usually progressive. Signs of subacute or chronic meningitis are accompanied by cranial nerve deficits (III, IV, VI), encephalitic syndrome, and/or signs of intracranial hypertension. Diagnosis: MRI reveals granulomatous cystic lesions with surrounding edema. Lung infiltrates may be seen. The nonspecific CSF changes include a variable (usually mild) lymphomonocytic pleocytosis as well as elevated protein, low glucose, and elevated lactate concentrations. An india ink histological preparation reveals the pathogen with a surrounding halo (carbon particles cannot penetrate its polysaccharide capsule). Identification of pathogen: demonstration of antigen in CSF and serum; tests for anticryptococcal antibody yield variable results. Treatment: initially, amphotericin B + flucytosine; subsequently, fluconazole or (if fluconazole is not tolerated) itraconazole.

! Candida (Candidiasis)

Candida albicans is a constituent of the normal body flora. In persons with impaired cell-medi-

ated immunity, Candida can infect the oropharynx (thrush) and then spread to the upper respiratory tract, esophagus, and intestine. CNS infection comes about by hematogenous spread (candida sepsis), resulting in meningitis or meningoencephalitis. Ocular changes: Candida endophthalmitis. Diagnosis:

Candida abscesses can be seen on CT or MRI. The CSF changes included pleocytosis (several hundred cells/µl) and elevated concentrations of protein and lactate. Pathogen identification: Microscopy, culture, or detection of specific antigens or antibodies. Local treatment: Amphotericin B or fluconazole. Systemic tratment: Amphotericin B + flucytosine.

! Aspergillus (Aspergillosis)

The mold Aspergillus fumigatus is commonly found in cellulose-containing materials such as silage grain, wood, paper, potting soil, and foliage. Inhaled spores produce local inflammation in the airways, sinuses, and lungs. Organisms reach the CNS by hematogenous spread or by direct extension (e. g., from osteomyelitis of the skull base, otitis, or mastoiditis), causing encephalitis, dural granulomas, or multiple abscesses. Diagnosis: CT and MRI reveal multiple, sometimes hemorrhagic lesions. The CSF findings include granulocytic pleocytosis and markedly elevated protein, decreased glucose, and elevated lactate concentration. Pathogen identification: Culture; if negative, then lung or brain biopsy. Treatment: Amphotericin B + flucytosine or itraconazole.

! Mucor, Absidia, Rhizopus (Mucormycosis)

Inhaled spores of these molds enter the nasopharynx, bronchi, and lungs, where they mainly infect blood vessels. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis is a rare complication of diabetic ketoacidosis, lymphoproliferative disorders, and drug abuse; infection spreads from the paranasal sinuses via blood vessels to the retro-orbi- tal tissues (causing retro-orbital edema, exophthalmos, and ophthalmoplegia) and to the brain (causing infarction with secondary hemorrhage). Diagnosis: CT, MRI; associated findings on ENT examination. Pathogen identification: Biopsy, smears. Treatment: Surgical excision of infected tissue if possible; amphotericin B.

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

CNS Infections

Candida albicans |

Pigeon feces |

(yeast form) |

Candidiasis of tongue (thrush)

Candida

Ink-stained CSF

specimen

Bright polysaccharide capsule, sprouting of daughter cells

Cryptococcosis

Cerebral aspergillosis (multiple hemorrhagic, necrotic foci)

Erythema, periorbital edema, exophthalmos, ptosis

Facial nerve palsy

Aspergillosis

Aspergillus fumigatus (hyphal filaments)

Bloody

nasal discharge

Rhinocerebral mucormycosis

Central Nervous System

249

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Central Nervous System

250

CNS Infections

Protozoan and Helminthic Infections

! Toxoplasma gondii (Toxoplasmosis)

This protozoan goes through three stages of development. Tachyzoites (endozoites; acute stage) are crescent-shaped, rapidly replicating forms that circulate in the bloodstream and are spread from one individual to another through contaminated blood or blood products. These develop into bradyzoites (cystozoites; latent stage), which aggregate to form tissue cysts (e. g., in muscle) containing several thousand organisms each. Oocysts are found only in the intestinal mucosa of the definitive host (domestic cat). Infectious sporozoites (sporulated oocysts) appear 2–4 days after the oocysts are eliminated in cat feces. Reuptake of the organism by the definitive host, or infection of an intermediate host (human, pig, sheep), occurs by ingestion of sporozoites from contaminated feces, or by consumption of raw meat containing tissue cysts. In the intermediate host, the sporozoites develop into tachyzoites, which then become bradyzoites and tissue cysts. Placental transmission (congenital toxoplasmosis hydrocephalus, intracellular calcium deposits, chorioretinitis) occurs only if the mother is initially infected during pregnancy. In immunocompetent persons, acute toxoplasmosis is usually asymptomatic, and only occasionally causes symptoms such as lymphadenopathy, fatigue, low-grade fever, arthralgia, and headache. IgG antibodies can be detected in latent toxoplasmosis (bradyzoite stage). In immunodeficient persons (p. 240), however, latent toxoplasmosis usually becomes symptomatic on reactivation. The central nervous system is most commonly affected (mainly encephalitis; myelitis is rare); other organs that may be affected include the eyes (chorioretinitis, iridocyclitis), heart, liver, spleen, PNS (neuritis) and muscles (myositis).

Diagnosis: EEG (slowing, focal signs), CT/MRI (solitary or multiple ring-enhancing abscesses), CSF (lymphomonocytic pleocytosis, mildly elevated protein concentration). Treatment: pyrimethamine/sulfadiazine or clindamycin/ folinic acid.

! Taenia solium (Neurocysticercosis)

tomatic infection of the human gut. Tapeworm segments that contain eggs (proglottids) are eliminated in the feces of pigs (the intermediate host) or humans with intestinal infection and then reingested by humans (or pigs) under poor hygienic conditions. The oval-shaped larvae pass through the intestinal wall and travel to multiple organs (including the eyes, skin, muscles, lung, and heart) by hematogenous, lymphatic, or direct spread. The CNS is often involved, though manifestations such as epileptic seizures, intracranial hypertension, behavioral changes (dementia, disorientation), hemiparesis, aphasia, and ataxia are uncommon. Spinal cysts are rare. Diagnosis: CT (solitary or multiple hypodense cysts with or without contrast enhancement, calcification and/or hydrocephalus), MRI (demonstration of cysts and surrounding edema), CSF examination (low-grade lymphocytic pleocytosis, occasional eosinophilia). Treatment: Praziquantel or albendazole; neurosurgical excision of intraventricular cysts; ventricular shunting in patients with hydrocephalus.

! Plasmodium falciparum (Cerebral Malaria)

This protozoan is most commonly transmitted by the bite of the female anopheles mosquito. Primary asexual reproduction of the organisms takes place in the hepatic parenchyma (preerythrocytic schizogony). The organisms then invade red blood cells and develop further inside them (intraerythrocytic development). The repeated liberation of merozoites causes recurrent episodes of fever. P. falciparum preferentially colonizes the capillaries of the brain, heart, liver, and kidneys. Pathogen identification: Blood culture. Treatment: See current topical literature for recommendations.

Ingestion of the tapeworm Taenia solium in raw or undercooked pork leads to a usually asymp-

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

CNS Infections

Placental transmission

EndoImmunodeficiency zoites

Oral transmission (sporulated oocysts, cysts in meat)

Toxoplasmosis

Sporulated oocysts

Hematogenous/lymphatic Contaminated raw spread pork

Infected porcine muscle (hydatid)

|

Contam- |

|

|

|

inated |

|

|

|

vegetables |

Intestinal |

|

|

Proglot- |

infection |

|

|

tids |

|

Cerebral cyst with mass effect |

|

|

Scolex |

(potential complications: |

|

|

meningitis, calcification, |

|

|

|

(head of |

obstructive hydrocephalus) |

|

|

tapeworm) |

|

|

Worm eggs |

Tapeworm |

|

Intermediate |

Cerebral cysticercosis |

|

|

host |

|

|

|

Endemic regions for malaria (current distribution may differ)

|

|

Multiple |

|

|

petechiae in |

|

|

cerebral |

Female anopheles mosquito |

Cerebral malaria |

malaria |

Central Nervous System

251

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Central Nervous System

252

CNS Infections

Transmissible Spongiform

Encephalopathies

The transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) are characterized by spongiform histological changes in the brain (vacuoles in neurons and neuropil), transmissibility to humans by way of infected tissue or contaminated surgical instruments, and, in some cases, a genetic determination. TSEs are transmitted by nucleic acidfree proteinaceous particles called prions and are associated with mutations in prion protein (PrP); they are therefore referred to as prion diseases.

Normal cellular prion protein (PrPc) is synthesized intracellularly, transported to the cell membrane, and returned to the cell interior by endocytosis. Part of the PrPc is then broken down by proteases, and another fraction is transported back to the cell surface. The physiological function of PrPc is still unknown. It is found in all mammalian species and is especially abundant in neurons. PRNP, the gene responsible for the expression of PrPc in man, is found on the short arm of chromosome 20. PRNP mutations yield the mutated form of PrP ( PrP) that causes the genetic spongiform encephalopathies. Another mutated form of PrP (PrPsc) causes the infectious spongiform encephalopathies. PrPsc induces the conversion of PrPc to PrPsc in the following manner: PrPsc enters the cell and binds with PrPc to yield a heterodimer. The resulting conformational change in the PrPc molecule (α-helical structure) and its interaction with a still unidentified cellular protein (protein X) transform it into PrPsc (#-sheet structure). Protein X is thought to supply the energy needed for protein folding, or at least to lower the activation energy for it. PrPsc cannot be formed in cells lacking PrPc. Mutated PrPsc presumably reaches the CNS by axonal transport or in lymphatic cells; these forms of transport have been demonstrated in forms of spongiform encephalopathies that affect domestic animals, e. g., scrapie (in sheep) and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE). PrP and PrPsc cannot be broken down intracellularly and therefore accumulate within the cells. Partial proteolysis of these proteins yields a protease-resistant molecule (PrP 27–30) that polymerizes to form amyloid, which, in turn, induces further neu-

ropathological changes. PrP and amyloid have been found in certain myopathies (such as inclusion body myositis, p. 344); others involve an accumulation of PrP (PrP overexpression myopathy).

! Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease (CJD)

CJD is a very rare disease, arising in ca. 1 person per 106 per year. It usually affects older adults (peak incidence around age 60). 85–90% of cases are sporadic (due to a spontaneous gene mutation or conformational change of PrPc to PrPsc); 5–15% are familial (usually autosomal dominant); and very rare cases are iatrogenic (transmitted by contaminated neurosurgical instruments or implants, growth hormone, and dural and corneal grafts). It usually progresses rapidly to death within 4–12 months of onset, though the survival time in individual cases varies from a few weeks to several years. Early manifestations are not typically seen, but may include fatigability, vertigo, cognitive impairment, anxiety, insomnia, hallucinations, increasing apathy, and depression. The principal finding is a rapidly progressive dementia associated with myoclonus, increased startle response, motor disturbances (rigidity, muscle atrophy, fasciculations, cerebellar ataxia), and visual disturbances. Late manifestations include akinetic mutism, severe myoclonus, epileptic seizures, and autonomic dysfunction. A new variant of CJD has recently arisen in the United Kingdom; unlike the typical form, it tends to affect younger patients, produces mainly behavioral changes in its early stages, and is associated with longer survival (though it, too, is fatal). It is thought to be caused by the consumption of beef from cattle infected with BSE. Diagnosis: EEG (1 Hz periodic biphasic or triphasic sharp-wave complexes), CT (cortical atrophy), T2/proton-weighted MRI (bilateral hyperintensity in basal ganglia in ca. 80%), CSF examination (elevation of neuron-specific enolase, S100# or tau protein concentration; presence of protein 14–3-3).

!Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker Disease (GSS) and Fatal Familial Insomnia (FFI)

See pp. 114 and 280.

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.