Color Atlas of Neurology

.pdf

|

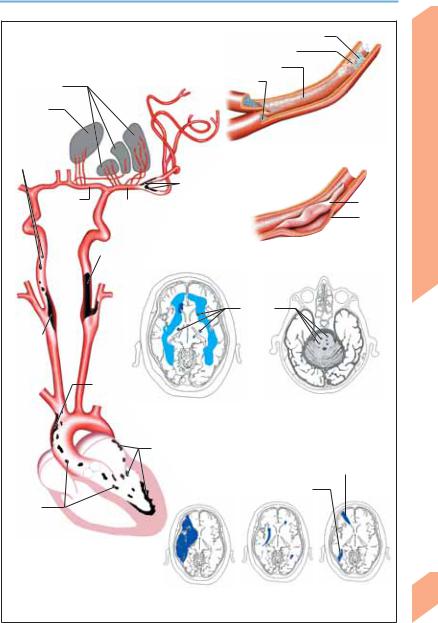

Stroke: Pathogenesis of Infarction |

|

||

|

Thrombus (source of embolism) |

|

||

|

Atherosclerosis (plaque) |

|

|

|

|

Thrombi |

|

|

|

Basal ganglia |

Embolus |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thalamus |

|

|

|

|

Arterio- |

|

Thromboembolism |

|

|

arterial |

|

|

|

|

thrombo- |

|

|

|

System |

emboli |

|

|

|

|

|

stenosis |

|

|

|

|

Intracranial arterial |

|

|

|

Anterior |

Middle |

|

Intima |

Nervous |

cerebral a. |

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

cerebral a. |

|

Media |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Carotid stenosis |

|

Arterial dissection |

Central |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

(hemodynamic |

|

|

|

|

disturbance) |

|

|

|

|

Lacunes |

|

|

|

Carotid |

|

|

|

|

stenosis |

|

|

|

|

|

Thrombus in |

|

|

|

|

aortic arch |

|

|

|

|

Subcortical arteriosclerotic |

|

Lacunar state |

|

|

encephalopathy |

|

(brain stem) |

|

|

Intracardiac thrombi |

|

|

|

|

(atrium, valves, ventricle) |

|

|

|

|

|

Middle/anterior cerebral a. |

|

|

|

Middle/posterior cerebral a. |

|

||

Cardio- |

|

|

|

|

genic |

|

|

|

|

thromboemboli |

|

|

|

|

Sources of thromboembolism |

|

|

|

|

|

Territorial infarct |

End zone |

Border zone |

173 |

|

(middle cerebral a.) |

infarcts |

infarcts |

|

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Central Nervous System

Stroke: Pathophysiology and Treatment

Stroke Pathophysiology

Hemodynamic insufficiency. Cerebrovascular autoregulation is normally able to maintain a relatively constant cerebral blood flow (CBF) of 50–60 ml/100 g brain tissue/min as long as the mean arterial pressure (MAP) remains within the range of 50–150 mmHg (p. 162). The regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) is finely adjusted according to local metabolic requirements (coupling of CBF and metabolism). If the MAP falls below 50 mmHg, and in certain pathological states (e. g., ischemia), autoregulation fails and CBF declines. Vascular stenosis or occlusion induces compensatory vasodilatation downstream, which increases the cerebral blood volume and CBF (vascular reserve); the extent of local brain injury depends on the availability of collateral flow, the duration of hemodynamic insufficiency, and the vulnerability of the particular brain region affected. Major neurological deficits arise only when CBF falls below the critical ischemia threshold (ca. 20 ml/100 g/min). Hypoperfusion. If adequate CBF is not reestablished, clinically evident neurological dysfunction ensues (breakdown of cerebral metabolismEEG and evoked potential change). Prolonged, severe depression of CBF below the infarction threshold of ca. 8–10 ml/100 g/min causes progressive and irreversible abolition of all cellular metabolic processes, accompanied by structural breakdown (necrosis). Infarction occurs where hypoperfusion is most severe; the area of tissue surrounding the zone of infarction in which the CBF lies between the thresholds for ischemia and infarction is called the ischemic penumbra. Brain tissue in the zone of infarction is irretrievably lost, while that in the ischemic penumbra is at risk, but potentially recoverable. The longer the ischemia lasts, the more likely infarction will occur; thus, time is brain. The zones of infarction and ischemia are well demonstrated by recently developed MRI techniques (DWI, PWI).1,2

Stroke Treatment

Primary prevention involves the therapeutic modification or elimination of risk factors.

Patients with asymptomatic stenosis are given antiplatelet therapy (APT) consisting of aspirin, aspirin–dipyridamole combination, or clopidogrel. Endarterectomy may be indicated in asymptomatic high-grade stenosis (!80%4 or

!90%3). Anticoagulants may be indicated in patients with atrial fibrillation without rheumatic valvular heart disease, depending on their individual risk profile (TIAs, age, comorbidities). Acute treatment is based on the existence of a 3–6-hour interval between the onset of ischemia and the occurrence of maximum irreversible tissue damage (treatment window).

General treatment measures include the assurance of adequate cardiorespiratory status (normal blood oxygenation is essential for the survival of the ischemic penumbra); because autoregulation of CBF in the penumbra is impaired, the systolic BP should be maintained above 160 mmHg. The serum glucose level should not be allowed to exceed 200 mg/100 ml. Balanced fluid replacement should be provided, and fever, if it occurs, should be treated. Physicians should be vigilant in the recognition and treatment of complications such as aspiration (secondary to dysphagia), deep venous thrombosis (secondary to immobility of a plegic limb), cardiac arrhythmia, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and pressure sores. Rehabilitation measures include physical, occupational, and speech therapy, as well as psychological counseling of the patient and family.

Special treatment measures: APT (after exclusion of hemorrhage); thrombolysis, treatment of cerebral edema, surgical decompression in space-occupying cerebellar or MCA infarcts, and anticonvulsants, as needed.

Secondary prevention. APT (TIA, mild stroke, atherothrombotic stroke); oral anticoagulation (cardiac embolism, arterial dissection); endarterectomy (in symptomatic carotid stenosis

!70%4, or !80%3, or after mild strokes). The potential utility and indications of carotid angioplasty and stenting in the treatment of carotid stenosis are currently under intensive study.

174 1Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) demonstrates the zone of infarction; the early CT signs of infarction (blurring of insular cortex, hypodensity of basal ganglia, cortical swelling) are less reliable.

2Perfusion-weighted imaging (PWI) demonstrates the ischemic penumbra and zone of oligemia (tissue at risk). 3Data from the European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST).

4Data from the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET).

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Stroke: Pathophysiology and Treatment

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

CBF (ml/100g/min) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hemodynamic |

Metabolic |

Penumbra |

|

Infarct |

|

|||

|

|

|

disturbances |

disturbances |

(TIA, reversible |

(Irreversible |

|

||||

|

|

|

(asymptomatic) |

(asymptomatic) |

|

||||||

50 |

|

|

|

|

deficit) |

|

|

deficit) |

|

||

|

|

|

|

O2U |

|

|

Cellular |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

40 |

|

|

|

O2 |

pH |

, |

|

Ca2+ |

|

||

|

CBV |

|

|

influx |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

30 |

|

CBV/CBF |

|

GU |

lactic acidosis |

Osmolysis |

|

||||

|

|

VGCC open |

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Normal O2U |

|

|

|

|||

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cell death |

|

|||

|

|

|

Free radicals |

Glutamate |

|

|

|

||||

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Decades |

|

Years |

Hours |

|

Minutes |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Time course of ischemic lesion |

CBF |

= |

Cerebral blood flow |

|||||||

|

development |

|

|

CBV |

= |

Cerebral blood volume |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

GU |

= |

Cerebral glucose utilization |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

O2 |

= |

Cerebral oxygen extraction |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

O2U |

= |

Cerebral oxygen utilization |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

VGCC = Voltage-gated calcium channels |

|||||

Arterial occlusion (no perfusion)

Penumbra

Region of infarction

Infarction threshold

Collateral vessel (vascular reserve)

Intact brain tissue

Collateral vessel

Ischemic threshold

Ischemic cascade

Central Nervous System

175

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Stroke: Intracranial Hemorrhage

Clinical Features

|

Spontaneous (i.e., |

nontraumatic) |

intracranial |

||

|

hemorrhage may be epidural, subdural (p. 267), |

||||

|

subarachnoid, intraparenchymal, or in- |

||||

|

traventricular. Its site and extent are readily |

||||

|

seen on CT (somewhat less well on MRI) and de- |

||||

|

termine its clinical manifestations. |

|

|

||

|

! Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH) |

|

|

||

|

Symptoms and signs. The typical presentation |

||||

System |

of aneurysmal rupture (by far the most common |

||||

cause of SAH) is with a very severe headache of |

|||||

abrupt onset (“the worst headache of my life”), |

|||||

|

|||||

|

often initially accompanied by nausea, vomit- |

||||

Nervous |

ing, diaphoresis, and impairment of conscious- |

||||

ness. The neck is stiff, and neck flexion is painful. |

|||||

There may also be focal neurological signs, pho- |

|||||

tophobia, and/or backache. Subarachnoid blood |

|||||

Central |

can be seen on CT within 24 hours of the hemor- |

||||

rhage in roughly 90% of cases. If SAH is sus- |

|||||

|

|||||

|

pected but the CT is negative, a diagnostic lum- |

||||

|

bar puncture must be performed. |

|

|

||

|

Complications. The initial hemorrhage may ex- |

||||

|

tend beyond the subarachnoid space into the |

||||

|

brain parenchyma, the subarachnoid space, and/ |

||||

|

or the ventricular system. A ruptured saccular |

||||

|

aneurysm may rebleed at any time until it is |

||||

|

definitively treated; the rebleed risk is highest on |

||||

|

the day of onset (day 0), and 40% in the ensuing 4 |

||||

|

weeks. The greater the amount of blood in the |

||||

|

subarachnoid cisterns, the more likely that va- |

||||

|

sospasm and delayed cerebral ischemia will occur; |

||||

|

the risk is highest between days 4 and 12. Clotted |

||||

|

blood blocking the ventricular system or the |

||||

|

arachnoid villi can lead to hydrocephalus, of ob- |

||||

|

structive or malresorptive type, respectively |

||||

|

(p. 162). Other complications include |

cerebral |

|||

|

edema, hyponatremia, neurogenic pulmonary |

||||

|

edema, seizures, and cardiac arrhythmias. |

||||

|

! Intracerebral Hemorrhage |

|

|

||

|

Intraparenchymal |

hemorrhages |

of |

arterial |

|

origin are to be distinguished from secondary hemorrhages into arterial or venous infarcts. General features. Sudden onset of headache, impairment of consciousness, nausea, vomiting, and focal neurological signs, with acute progres-

176sion over minutes or hours.

Hemorrhage into the basal ganglia. Putaminal

hemorrhage produces contralateral hemipare-

sis/hemiplegia and hemisensory deficit, conjugate horizontal gaze deviation, homonymous hemianopsia, and aphasia (dominant side) or hemineglect (nondominant side). Thalamic hemorrhage produces similar manifestations and also vertical gaze palsy, miotic, unreactive pupils, and (sometimes) convergence paresis. The very rare caudate hemorrhages are characterized by confusion, disorientation, and contralateral hemiparesis. Hemorrhage into the basal ganglia and internal capsule leads to coma, contralateral hemiplegia, homonymous hemianopsia, and aphasia (dominant side).

Lobar hemorrhage usually originates at the gray–white matter junction and extends inward into the white matter, producing variable clinical manifestations. Frontal lobe: Frontal headache, abulia, contralateral hemiparesis (arm more than leg). Temporal lobe: Pain around the ear, aphasia (dominant side), confusion, upper quadrantanopsia. Parietal lobe: Temporal headache, contralateral sensory deficit, aphasia, lower quadrantanopsia. Occipital lobe: Ipsilateral periorbital pain, hemianopsia.

Cerebellar hemorrhages are usually restricted to one hemisphere. They produce nausea, vomiting, severe occipital headache, dizziness, and ataxia.

Brain stem hemorrhage. Pontine hemorrhage is the most common type, producing coma, quadriplegia/decerebration, bilateral miosis (pinpoint pupils), “ocular bobbing,” and horizontal gaze palsy. Locked-in syndrome may ensue.

General complications. Intraventricular extension of hemorrhage, hydrocephalus, cerebral edema, intracranial hypertension, seizures, and hemodynamic changes (often a dangerous elevation of blood pressure).

! Intraventricular Hemorrhage

Intraventricular hemorrhage only rarely originates in the ventricle itself (choroid plexus). It is much more commonly the intraventricular extension of an aneurysmal SAH or other brain hemorrhage.

Symptoms and signs. Acute onset of headache, nausea, vomiting, impairment of consciousness or coma.

Complications. Extension of hemorrhage, hydrocephalus, seizures.

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Stroke: Intracranial Hemorrhage

Retinal hemorrhage in SAH

Headache of SAH

Hemorrhage into basal ganglia/thalamus

|

Hemorrhage |

|

Cotton-wool |

|

Accumulation |

|

of blood in |

|

spots |

|

|

|

subarachnoid space |

|

|

Hypertensive changes in |

|

|

|

|

|

ocular fundus (grade 3) |

|

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) |

|

|

Lobar hemorrhage |

Brain stem |

|

Cerebellar |

|

|||

|

hemorrhage |

hemorrhage |

|

Intraventricular hemorrhage

Intracranial hemorrhages (mass effect not shown)

Central Nervous System

177

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Central Nervous System

178

Stroke: Intracranial Hemorrhage

Pathogenesis

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Roughly 85% of cases of SAH are caused by rupture of a saccular aneurysm at the base of the skull. Another 10% are caused by nonaneurysmal lesions (whose nature is not, at present, understood), with bleeding mainly in the perimesencephalic cisterns (p. 8). Other, rare, causes include vertebral artery dissection, arteriovenous malformation (AVM), cavernoma, hypertension, anticoagulation, and trauma.

Aneurysm. An aneurysm is not a congenital lesion, but a progressive, localized dilatation of an arterial wall. Saccular aneurysms tend to develop at branching sites of the internal carotid artery (ICA), the anterior communicating artery, and the proximal middle cerebral artery (MCA). Fusiform aneurysms usually appear as an elongated, twisted, and dilated segment (dolichoectasis) of the basilar artery or supraclinoid ICA. Most are due to atherosclerosis. Spontaneous hemorrhage is rare; ischemia due to arterioarterial embolism is more common. The rare septic-embolic aneurysms (mycotic aneurysms) may be secondary to endocarditis, meningoencephalitis, hemodialysis, or intravenous drug administration. They are located in distal vessel segments, particularly in the MCA, and may cause SAH, massive hemorrhage, or infarction with secondary hemorrhage.

Vascular malformations. Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are congenital lesions consisting of a tangled web of arteries and veins with pathological arteriovenous shunting. Most are located near the surface of the cerebral hemispheres. AVMs tend to enlarge over time and may become calcified. They may cause subarachnoid or intracerebral hemorrhage at any age. They become clinically manifest either through a hemorrhage or through headache, seizures, or focal neurological signs (aphasia, hemiparesis, hemianopsia).

Cavernomas are compact, often calcified, aggregations of dilated blood vessels and connective tissue in the brain and leptomeninges. They rarely bleed (ca. 0.5%/year). Some cause seizures and focal deficits; others are discovered on MRI scans as an incidental finding.

Intracerebral hemorrhage. Hypertension is the most common cause; other causes include

aneurysm, AVM, cerebral amyloid angiography, moyamoya, coagulopathy (leukemia, thrombocytopenia, therapeutic anticoagulation), cerebral vasculitis, cerebral venous thrombosis, drug abuse (cocaine, heroin), alcohol, metastases, and brain tumors. Massive hypertensive hemorrhage is thought to be caused by pressure-in- duced rupture of arterioles and microaneurysms. The high pressure and a kind of chain reaction involving multiple microaneurysms is thought to explain the size of these hemorrhages (despite the small caliber of the ruptured vessels). The recurrent, mainly cortical, bleeding associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy is due to the fragility of leptomeningeal and cortical small vessels in whose walls amyloid deposits have accumulated.

Dural fistula is an abnormal anastomosis between dural arteries and a venous sinus. Hemorrhage is rare; they may cause pulsating tinnitus, headache, papilledema, and visual disturbances.

Treatment

Aneurysmal hemorrhage. Cautious transport, bed rest, analgesia, admission to a neurosurgical unit, and angiography to establish the diagnosis and define the anatomy of the aneurysm(s). The timing of surgical clipping depends on the site and clinical severity of the hemorrhage, the aneurysm’s configuration, and the age and general medical condition of the patient. Inoperable cases can be managed with intravascular neuroradiological techniques (“embolization”; filling with Guglielmi detachable coils (GDC) is currently favored).

Hemorrhage from an AVM may be treated with surgery, embolization, and/or stereotactic radiosurgery, depending on its site and extent. Cavernomas that bleed are usually excised.

Intracerebral hemorrhage is often treated conservatively, unless it impairs consciousness or causes a progressive neurological deficit. Major cerebellar hemorrhage (rule of thumb: !3 cm) is life-threatening unless treated neurosurgically.

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Stroke: Intracranial Hemorrhage

Middle cerebral a.

Anterior communicating a.

|

|

|

|

Posterior |

|

|

|

|

|

communi- |

|

|

|

|

|

cating a. |

|

Anterior cerebral a. |

|

|

|

||

Basilar a. |

|

|

|

|

Posterior |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Internal carotid a. |

|

|

|

cerebral a. |

|

|

|

|

|||

Source of hemorrhage |

|

|

Vertebral a. |

||

|

|

||||

(saccular aneurysm) |

|

|

|

||

Ruptured aneurysm |

Common aneurysm sites |

||||

|

|

|

Vessel wall damage |

||

Microaneurysms |

Lenticulostriate |

|

arteries |

|

Cavernoma |

Arteriovenous malformation |

Cavernoma (MRI) |

Central Nervous System

179

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Central Nervous System

Stroke: Sinus Thrombosis, Vasculitis

Sinus Thrombosis

Symptoms and signs. Aseptic sinus thrombosis most commonly affects the superior sagittal sinus and produces initial headache, vomiting, and focal epileptic seizures, followed by monoparesis or hemiparesis, papilledema, abulia, and impairmentofconsciousness. Blockageofvenous outflowcausescerebraledemaandruptureofthe distended cerebral veins upstream from the thrombosis.Septicsinusthrombosis isheraldedby fever, chills, and malaise. Pain, redness, and swelling of the eye or ear may develop, in addition to focal neurological signs. Transverse and sigmoid sinus thromboses are often secondary to ear and mastoidinfections,whilecavernoussinusthrombosis is often due to infections about the face (orbit, paranasal sinuses, teeth).

Etiology. Aseptic sinus thrombosis may occur duringorafterpregnancy,orsecondarytotheuse of oral contraceptives, deficiencies of protein C, protein S, antithrombin III, or factor V, dehydration, polycythemia vera, leukemia, Behçet disease, trauma, surgical procedures, and malignancy. Septic sinus thrombosis often occurs by secondary spread of infections about the head (sinusitis, otitis media, mastoiditis, facial furuncle). Identification: CT or MRI angiography generally suffices to demonstrate the occluded sinus;conventionalangiographyisrarelyneeded.

Treatment. Aseptic thrombosis: anticoagulation.

Septic thrombosis (pp. 226, 375): antibiotics and surgical management of the source of infection.

Cerebral Vasculitis

Primary vasculitis arises in the cerebral arteries and veins themselves, while secondary vasculitis is a sequela of another disease (see Causes, below).

Symptoms and signs. Cerebral vasculitis produces variable symptoms and signs, including recurrent ischemia, intracerebral or subarachnoid hemorrhage, persistent headache, focal epilepsy, gradually progressive focal neurological signs, dementia, behavioral abnormalities, cranial nerve palsies, and meningismus. Vasculitis may also affect vessels of the spinal cord (transverse cord syndrome) and those supplying the peripheral nerves (painful mononeuropathy).

Causes. Isolated cerebral angiitis (idiopathic) is difficult to diagnose because its findings are nonspecific (elevated CSF protein, EEG and MRI abnormalities). Leptomeningeal biopsy may be needed. Primary or secondary vasculitides of various kinds affect the vessels of the central nervous system (CNS), peripheral nervous system (PNS) and/or skeletal muscles to a variable extent (see table).

Treatment. Infectious vasculitis is treated with antiviral or antibacterial agents, as needed, while autoimmune vasculitis is treated with corticosteroids and immune suppressants (cyclophosphamide, azathioprine).

|

|

Syndrome |

CNS |

PNS |

Muscle |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Churg–Strauss syndrome |

++ |

+++ |

+ |

|

|

Wegener granulomatosis |

++ |

++ |

+ |

|

|

Behçet disease |

++ |

+/– |

– |

|

|

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis |

++ |

+/– |

– |

|

|

Syphilis, tuberculosis, herpes zoster, bacterial meningitis, |

++ |

+/– |

+/– |

|

|

fungal infection |

|

|

|

|

|

Temporal arteritis |

+ |

+/– |

– |

|

|

Polyarteritis nodosa |

+ |

+++ |

+ |

|

|||||

|

|

Takayasu arteritis |

+ |

– |

– |

180 |

|

Lymphoma |

+ |

+ |

– |

|

|

||||

|

+++ usual, ++ common, + occasional, +/– rare, – absent |

|

(From Moore and Calabrese, 1994) |

||

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Stroke: Sinus Thrombosis, Vasculitis

Confluence of sinuses |

Transverse sinus |

Superior sagittal sinus |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sigmoid sinus |

|

|

Cerebral veins (normal MR angiogram) |

|

Perivascular hemorrhage |

Thrombosed segment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MRI scan (sagittal) |

|

|

|

Aseptic sinus thrombosis |

|

|

|

CT scan (axial) |

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

Large to |

|

|

|

|

Capillary |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

medium-sized |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

artery |

Small |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Arteriole |

Venule |

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

artery |

Vein |

|||||||||||

Aorta |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cutaneous |

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

leukocytoclastic |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

angiitis |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

Schönlein |

-Henoch vasculitis and essential |

cryoglobulinemia |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Microscopic polyangiitis |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Wegener |

granulomatosis, Churg-Strauss syndrome |

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

Polyarteritis |

nodosa, Kawasaki disease |

|

|

Immune vasculitis |

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(gray: regions most commonly |

|||

|

|

|

Temporal arteritis, Takayasu arteritis |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

affected by systemic vasculitis) |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

Central Nervous System

181

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Central Nervous System

Headache

Tension Headache

Tension headache often involves painful cervical muscle spasm, may change with the weather, and is frequently ascribed by patients and others to cervical spinal degenerative disease, visual disturbance, or life stress. It consists of a bilateral, prominent nuchal pressure sensation that progresses over the course of the day. Patients may report feeling as if their head were being squeezed in a vise or by a band being drawn ever more tightly around it, or as if their head were about to explode, though the pain is rarely so severe as to impede performance of the usual daily tasks, e. g., at work. It may be accompanied by malaise, anorexia, lack of concentration, emotional lability, chest pain, and mild hypersensitivity to light and noise. Unlike migraine, it is not aggravated by exertion (e. g., climbing stairs), nor does it produce vomiting or focal neurological deficits. It can be episodic (!15 days/month, pain lasting from 30 minutes to 1 week) or chronic ("15 days/month for at least 6 months). Some patients suffer from pericranial tenderness (posterior cervical, masticatory, and cranial muscles). Isolated attacks of sudden, stabbing pain (ice-pick headache) may occur on one side of the head or neck. Tension headache rarely wakes the patient from sleep. Its cause usually cannot be determined, though it may be due to disorders of the temporomandibular joint or psychosomatic troubles such as stress, depression, anxiety, inadequate sleep, or substance abuse. Tension headache combined with migraine is termed combination headache. Pathogenesis. It is theorized that diminished activity of certain neurotransmitters (e. g., endogenous opioids, serotonin) may lead to abnormal nociceptive processing (p. 108) and thus produce a pathological pain state.

Headache Due to Vascular Processes (Other than Migraine)

the actual vascular event (arterial dissection, arteriovenous malformation, vasculitis), may occur simultaneously with the event (subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracerebral hemorrhage, epidural hematoma, cerebral venous thrombosis, giant cell arteritis, carotidynia, venous outflow obstruction in goiter or mediastinal processes, pheochromocytoma, preeclampsia, malignant hypertension), or may follow the event (subdural hematoma, intracerebral hemorrhage, endarterectomy).

Chronic Daily Headache

Rational treatment is based on the classification of primary daily headache by clinical characteristics (see Table 23, p. 373), and of secondary (symptomatic) headache by etiology.

The nociceptive innervation of the extracranial and intracranial vessels is of such a nature that pain arising from them is often projected to a site in the head that is some distance away from

182the responsible lesion. Thus, specific diagnostic studies are usually needed to pinpoint the location of the disturbance. The pain may precede

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.