A Dictionary of Science

.pdf

349 |

Gell-Mann, Murray |

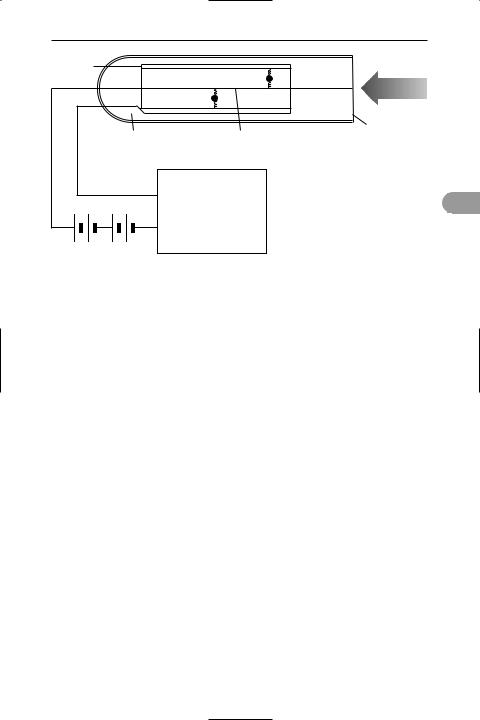

cylindrical |

|

|

cathode |

|

|

|

|

radiation |

|

|

window |

|

low-pressure gas |

fine wire anode |

+ |

– |

|

|

|

g |

|

|

amplifier and counter |

high-voltage source

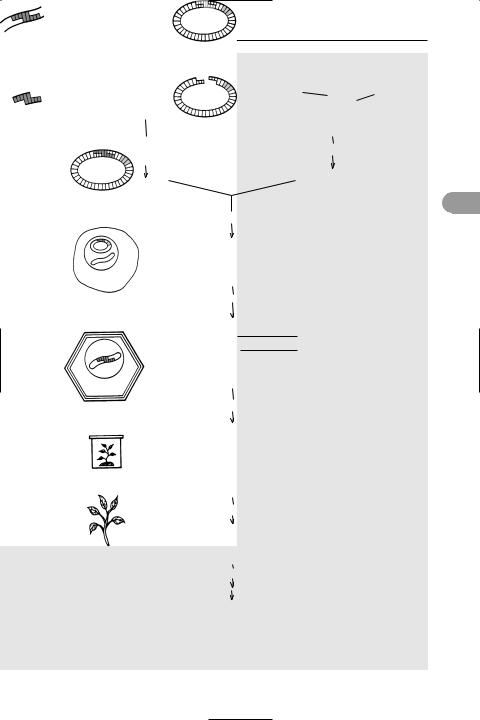

Geiger counter |

|

|

(see illustration). A potential difference of |

tion that sets to a gel on cooling. It is used |

|

about 1000 volts is maintained between |

in photographic emulsions and adhesives, |

|

the electrodes. An ionizing particle or |

in bacteriology for preparing culture |

|

photon passing through a window into |

media, in pharmacy for preparing cap- |

|

the tube will cause an ion to be produced |

sules and suppositories, and in jellies and |

|

and the high p.d. will accelerate it to- |

other foodstuffs. |

|

wards its appropriate electrode, causing |

gel electrophoresis See electropho- |

|

an avalanche of further ionizations by col- |

||

resis. |

||

lision. The consequent current pulses can |

||

|

||

be counted in electronic circuits or simply |

gel Ültration A type of column *chro- |

|

ampliÜed to work a small loudspeaker in |

matography in which a mixture of liquids |

|

the instrument. It was Ürst devised in |

is passed down a column containing a gel. |

|

1908 by Hans Geiger. Geiger and W. |

Small molecules in the mixture can enter |

|

Müller produced an improved design in |

pores in the gel and move slowly down |

|

1928. |

the column; large molecules, which can- |

|

Geissler tube An early form of gas- |

not enter the pores, move more quickly. |

|

discharge tube designed to demonstrate |

Thus, mixtures of molecules can be sepa- |

|

rated on the basis of their size. The tech- |

||

the luminous effects of an electric dis- |

||

nique is used particularly for separating |

||

charge passing through a low-pressure gas |

||

between two electrodes. ModiÜed forms |

proteins but it can also be applied to |

|

are used in spectroscopy as a source of |

other polymers and to cell nuclei, viruses, |

|

light. It was invented in 1858 by Heinrich |

etc. |

|

Geissler (1814–79). |

gelignite A high explosive made from |

|

|

||

gel A lyophilic *colloid that has coagu- |

nitroglycerin, cellulose nitrate, sodium ni- |

|

lated to a rigid or jelly-like solid. In a gel, |

trate, and wood pulp. |

|

the disperse medium has formed a |

Gell-Mann, Murray (1929– ) US theo- |

|

loosely-held network of linked molecules |

||

retical physicist, who held a professorship |

||

through the dispersion medium. Exam- |

||

at the California Institute of Technology. |

||

ples of gels are silica gel and gelatin. |

||

In 1955 he proposed the property of |

||

|

||

gelatin(e) A colourless or pale yellow |

*strangeness for certain fundamental par- |

|

water-soluble protein obtained by boiling |

ticles. In 1961 he and Yuval Ne’eman |

|

collagen with water and evaporating the |

(1925– ) proposed the eightfold way to |

|

solution. It swells when water is added |

deÜne the structure of particles. This led |

|

and dissolves in hot water to form a solu- |

to Gell-Mann’s postulate of the quark (see |

352

GENETICALLY MODIFIED ORGANISMS

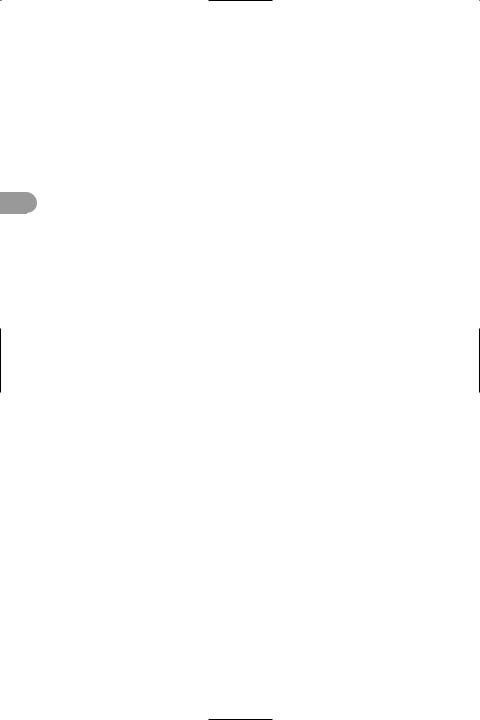

Since the early 1980s developments in genetic engineering have made it possible to produce genetically modified organisms. A gene from one organism is isolated and transfered to cells of another organism, where it is incorporated into the recipient’s chromosomes and expressed. Such transgenic organisms can exhibit quite novel characteristics. During the 1990s there was a dramatic growth in the commercial applications of this new technology, ranging from the production of human hormones in bacteria and vaccines in yeasts to the development of genetically modified (GM) crop plants.

Techniques

Various methods are used to introduce novel genes, depending on the nature

gof the recipient organism. Much of the work with genetic modification of plants involves {protoplasts}, cultured spherical cells from which the cell walls have been removed. The Ti plasmid (see illustration) of A. tumefaciens has been used successfully as a {vector} with certain dicotyledons, including tobacco, tomato, potato, soyabean, and cotton. It works much less well with grasses, cereals, and other monocots. In these plants various other techniques are available, including:

■electroporation – treatment of cells by exposure to an electric field that renders them transiently permeable to DNA fragments;

■microinjection – injection of DNA directly into the cell nucleus;

■biolistics – ‘shooting’ a cell with a DNA-coated tungsten microprojectile.

To produce a transgenic animal the novel genes are inserted at a very early stage of development, e.g. the early embryo or the pronucleus of a fertilized egg, typically using microinjection. The recombinant embryos are then transferred to the uterus of a foster mother to complete their development.

Applications

Plants

■tolerance to herbicides

■improved insect resistance

■‘vaccination’ against specific diseases

■longer ‘shelf life’ for fruit

Animals

■production of therapeutic proteins in milk

■potential for improved growth rates and milk yields

■potential for production of organs for human transplants

Risks

The use of GM organisms in the environment poses certain potential problems. For example, genes for herbicide or insect resistance may spread from crop plants to wild plants, with possible serious consequences for both agriculture and natural ecosystems. Farmers may be faced with new ‘superweeds’, while insect populations could decline. Moreover, the products of GM crops have to be fully evaluated to ensure that they are safe to eat. Genetic modification of animals often has unforeseen side-effects and raises ethical issues about such treatments.

In plants one of the most useful cloning vectors is the Ti plasmid of the bacterium Agrobacterium tumefaciens, which is responsible for a plant tumour known as crown-gall disease. The plasmid is engineered by replacing its tumour-inducing genes (T-DNA) with the gene to be cloned and then returned to the bacterium, which is allowed to infect cultured plant protoplasts. Transformed cells are selected by the presence of marker genes and propagated with plant growth substances so they develop into complete plants.