R.Daft Understanding Management

.pdf

Licensed to: CengageBrain User

10 |

|

|

|

Chapter 1 Innovative Management for a Changing World |

|

|

|

|

|

Organizational Performance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The second part of our definition of management is the attainment of organizational goals |

|

|

|

|

|

in an efficient and effective manner. Management is so important because organizations are |

|

|

|

|

|

so important. In an industrialized society where complex technologies dominate, organiza- |

|

|

|

|

|

tions bring together knowledge, people, and raw materials to perform tasks no individual |

|

|

|

|

|

could do alone. Without organizations, how could technology be provided that enables |

|

|

|

|

|

us to share information around the world in an instant; electricity be produced from huge |

|

|

|

|

|

dams and nuclear power plants; and millions of songs, videos, and games be available for |

|

|

|

|

|

our entertainment at any time and place? Organizations pervade our society, and managers |

|

|

|

|

|

are responsible for seeing that resources are used wisely to attain organizational goals. |

|

|

|

|

|

Our formal definition of an organization is a social entity that is goal directed and de- |

|

|

|

|

|

liberately structured. Social entity means being made up of two or more people. Goal directed |

|

|

|

|

|

means designed to achieve some outcome, such as make a profit (Walmart), win pay increases |

|

|

|

|

|

for members (AFL-CIO), meet spiritual needs (United Methodist Church), or provide social |

|

|

|

|

|

satisfaction (college sorority). Deliberately structured means that tasks are divided and respon- |

|

|

|

|

|

sibility for their performance is assigned to organization members. This definition applies to |

|

|

|

|

|

all organizations, including both profit and nonprofit. Small, offbeat, and nonprofit organiza- |

|

|

|

|

|

tions are more numerous than large, visible corporations—and just as important to society. |

|

|

|

|

|

Based on our definition of management, the manager’s responsibility is to coordi- |

|

|

|

|

|

nate resources in an effective and efficient manner to accomplish the organization’s goals. |

|

|

|

|

|

Organizational effectiveness is the degree to which the organization achieves a stated |

|

|

|

|

|

goal, or succeeds in accomplishing what it tries to do. Organizational effectiveness means |

|

|

|

|

|

providing a product or service that customers value. Organizational efficiency refers to |

|

|

|

|

|

the amount of resources used to achieve an organizational goal. It is based on how much |

|

|

|

|

|

raw material, money, and people are necessary for producing a given volume of output. |

|

|

|

|

|

Efficiency can be calculated as the amount of resources used to produce a product or |

|

|

|

|

|

service. Efficiency and effectiveness can both be high in the same organization. Managers |

|

|

|

|

|

at retailer Target, for instance, continually look for ways to increase efficiency while also |

|

|

|

|

|

meeting the company’s quality and customer satisfaction goals. |

|

|

Target |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

xpect more, pay less. An astonishing 97 percent of Americans recognize Target’s red- |

|||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

and-white bull’s-eye logo, and almost as many are familiar with the slogan: “Pay less, |

|

|

|

|

|

Eexpect more.” “Sometimes we focus a little bit more on the ‘pay less,’ sometimes on |

|

|

|

|

|

the ‘expect more,’ but the guardrails are there,” says Gregg Steinhafel, who took over as CEO |

|

|

|

|

|

of the trendy retailer in May 2008. |

|

|

|

|

|

Target’s slogan not only offers a promise to customers, it also reflects the company’s |

|

|

|

|

|

emphasis on both effectiveness and efficiency. Target has an elite, secret team, called the |

|

|

|

|

|

“creative cabinet,” made up of outsiders of various ages, interests, and nationalities who pro- |

|

|

|

|

|

vide ideas and insights that keep the company on the cutting edge of consumer trends and |

|

|

|

|

|

who give their input regarding managers’ strategic initiatives. Innovation, design, and quality |

|

|

|

|

|

are key goals, and managers focus on providing a fun store experience and a unique, exciting |

|

|

|

|

|

product line. At the same time, they keep a close eye on costs and operating efficiencies to |

|

|

|

|

|

keep prices low. “I talk a lot about gross margin rate and the key drivers to improve our metrics |

|

|

|

|

|

and performance,” Steinhafel says. In its SuperTarget centers, the retailer is able to consis- |

|

|

|

|

|

tently underprice supermarkets on groceries by about 10 percent to 15 percent, and it comes |

|

|

|

|

|

very close to Walmart’s rock-bottom prices. |

|

|

|

|

|

In today’s slow economy, Target, like other retailers, has had to adjust worker hours and |

|

|

|

|

|

look for other efficiencies, which has drawn unfavorable attention from worker advocacy |

|

|

|

|

|

groups. Managers have to walk a fine line to continue to meet their goals for both efficiency |

|

|

|

|

|

and effectiveness.6 |

|

|

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). |

||||

|

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. |

||||

Licensed to: CengageBrain User

Management Skills |

11 |

All managers have to pay attention to costs, but severe cost cutting to improve efficiency can sometimes hurt organizational effectiveness. The ultimate responsibility of managers is to achieve high performance, which is the attainment of organizational goals by using resources in an efficient and effective manner. Consider what happened at music company EMI. Weak sales led managers to focus on financial efficiency, which successfully trimmed waste and boosted operating income. However, the efficiencies damaged the company’s ability to recruit new artists, who are vital to record companies, and also led to internal turmoil that caused some long-time acts to leave the label. Thus, the company’s overall performance suffered. Managers are struggling to find the right balance between efficiency and effectiveness to get EMI back on the right track.7

•An organization is a social entity that is goal directed and deliberately structured.

•Good management is important because organizations contribute so much to society.

•Efficiency pertains to the amount of resources—raw materials, money, and people—used to produce a desired volume of output.

•Effectiveness refers to the degree to which the organization achieves a stated goal.

•Performance is defined as the organization’s ability to attain its goals by using resources in an efficient and effective manner.

•The marketing slogan for retailer Target reflects managers’ concern with both keeping costs low (efficiency) and meeting customers’ needs (effectiveness).

Management Skills

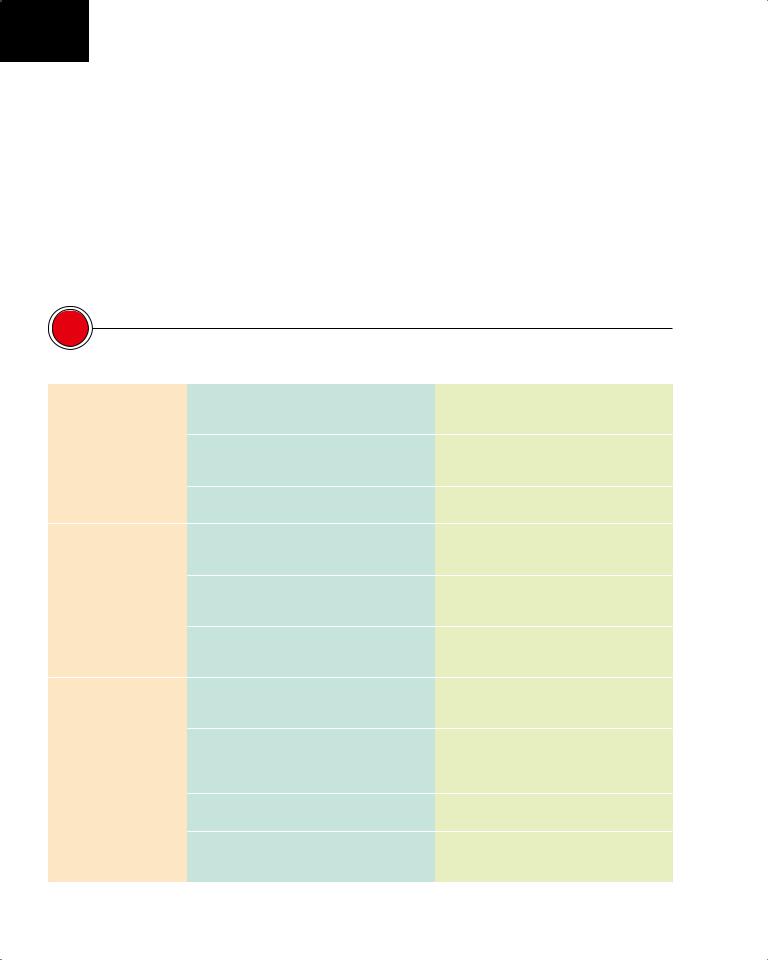

A manager’s job is complex and multidimensional and, as we shall see throughout this book, requires a range of skills. Although some management theorists propose a long list of skills, the necessary skills for managing a department or an organization can be summarized in three categories: conceptual, human, and technical.8 As illustrated in Exhibit 1.2, the application of these skills changes as managers move up in the organization. Although the degree of each skill necessary at different levels of an organization may vary, to perform effectively all managers must possess skills in each of these important areas.

When Skills Fail

Everyone has flaws and weaknesses, and these shortcomings become most apparent under conditions of rapid change, uncertainty, or crisis.9 Consider how Tony Hayward, a geologist by training, handled the BP Deepwater Horizon crisis in the Gulf of Mexico that ended his career as CEO and further damaged BP’s reputation. Until the spring of 2010, Hayward had been praised for leading a successful turnaround at the oil giant. Yet, after an oil rig drilling a well for BP exploded, killing 11 workers and sending hundreds of millions of gallons of oil spewing into the Gulf of Mexico, Hayward faltered in his role as a crisis leader. His ill-advised comment that he wanted the crisis over as much as anyone because he “wanted his life back” showed an insensitivity and lack of diplomacy that roiled the public. One crisis expert, Robbie Vorhaus, says Hayward basically failed in the task of “becoming human” to people affected by the disaster, a failure that eventually led to calls for his ouster. Hayward resigned in July of 2010. “All of a sudden, you have

Complete the Readiness for Management instrument, on p. 14, that pertains to how prepared you are to take on a management role. Reflect on the strength of your preferences among the skills, and the implications for you as a manager.

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Licensed to: CengageBrain User

12 |

Chapter 1 Innovative Management for a Changing World |

1.2

EXHIBIT

Relationship of Conceptual, Human, and Technical Skills to Management

Conceptual Skills |

Human Skills |

Technical |

Skills |

Conceptual Skills |

Human Skills |

Technical Skills |

Conceptual Skills |

Human Skills |

Technical Skills |

Skills |

Human Skills |

Technical Skills |

CengageLearning 2013 |

|

Managers |

Middle Managers |

First-Line Managers |

Nonmanagers |

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conceptual |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(Individual Contributors) © |

||||

an event where you are now standing in the spotlight among shrimp fishermen and local politicians, and people who maybe make 20[,000] or 30,000 dollars a year,” Vorhaus said. “A true leader needs to be able to come from the heart and make people feel that there is a connection.”10

During turbulent times, managers really have to stay on their toes and apply all their skills and competencies in a way that benefits the organization and its stakeholders— employees, customers, investors, the community, and so forth. In recent years, numerous highly publicized examples have shown what happens when managers fail to effectively apply their skills to meet the demands of an uncertain, rapidly changing world. Ethical and financial scandals and the failure of companies in the finance and auto industries have left people cynical about business managers and even less willing to overlook mistakes. Sometimes a leader’s ego can prevent the use of one’s skills, as happened with Leslie Singer, described in the Business Blooper.

Crises and examples of corporate deceit and greed grab the headlines, but many more companies falter or fail less spectacularly. Managers fail to listen to customers, are unable to motivate employees, or can’t build a cohesive team.

•Managers have complex jobs that require a range of abilities and skills, including conceptual, human, and technical.

•The two major reasons managers fail are poor communication and poor interpersonal skills.

•A manager’s weaknesses become more apparent during stressful times of uncertainty, change, or crisis.

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Licensed to: CengageBrain User

What Is It Like to Be a Manager? |

13 |

© Pixel 4 Images, Shutterstock

Business BLOOPER

Leslie Singer, Inc.

esigner par excellence Leslie Singer started D her own accessory line, Leslie Singer, using imaginative psychedelic images that were in- spiredbythepattern-heavymodelsofBurberry.

Her unique designs were noticed by designers and loved by consumers. She started to do trunk shows and got great response from boutiques across the country. Only problem: they saw her as very small and therefore placed tiny orders, maybe two dozen scarves each time. Big stores wouldn’t even deal with her because of her size. Or else they’d ask her to redesign her collection to match the trend this year, something she felt compromised her artistic vision. Four years and $500,000 later, she “86’d” the business and went back to what she knew she could do successfully, branding and marketing, in her company

HS Dominion. After much reflection, Singer realizes she did not do enough homework in high-volume fashion retail. “I never looked at the retailer side, at shows they buy, what the decision process is based on, who the gatekeepers are,” she says.

Because she had been so admired by her peers, she also sees that her overconfidence prevented her from doing the necessary legwork, as she assumed previous achievements would transform into the fashion world’s open doors. “Not getting that was a crushing blow to my ego.”

SOUrcE: Malika Zouhali-Worrall, “Learning the Hard Way: Up to Her Neck in Small Orders,” INC Magazine, October 2010, p, 70.

What Is It Like to Be a Manager?

Unless someone has actually performed managerial work, it is hard to understand exactly what managers do on an hour-by-hour, day-to-day basis. One answer to the question of what managers actually do to plan, organize, lead, and control was provided by Henry Mintzberg, who followed managers around and recorded all their activities.11 He developed a description of managerial work that included three general characteristics and ten roles. These characteristics and roles, discussed in detail later in this section, have been supported by other research.12

Researchers have also looked at what managers like to do. Both male and female managers across five different countries report that they most enjoy activities such as leading others, networking, and leading innovation. Activities managers like least include controlling subordinates, handling paperwork, and managing time pressures.13 Many new managers, in particular, find the intense time pressures of management, the load of administrative paperwork, and the challenge of directing others to be quite stressful as they adjust to their new roles and responsibilities. Indeed, the initial leap into management can be one of the scariest moments in a person’s career.

Making the Leap: Becoming a New Manager

Many people who are promoted into a manager position have little idea what the job actually entails and receive little training about how to handle their new role. It’s no wonder that, among managers, first-line supervisors tend to experience the most job burnout and attrition.14

Organizations often promote the star performers—those who demonstrate individual expertise in their area of responsibility and have an ability to work well with

How will you make the transition to a new manager’s position? Complete the New Manager Self-Test on page 7, to see how prepared you are to step into a management role.

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Licensed to: CengageBrain User

14 |

Chapter 1 Innovative Management for a Changing World |

Spotlight ON SKILLS

What’s Your Readiness for Management?

© Bata Zivanovic, Shutterstock

W |

elcome to the world of management. Are you |

new manager of a department. Your task is to |

|

ready for it? This questionnaire will help you |

rate the top four priority items as “High Priority” |

||

see whether your priorities align with the de- |

and the other four as “Low Priority”; in other |

||

mands placed on today’s managers. Rate |

words, You will have four of the items rated |

||

each of the |

following items based on what you think is the |

high and four rated low. |

|

appropriate emphasis for that task to your success as a |

|

|

|

|

|

High Priority <<< |

>>> Low Priority |

1.Spend 50 percent or more of your time in the care and feeding of people.

2.Make sure people understand that you are in control of the department.

3.Use lunches to meet and network with peers in other departments.

4.Implement the changes you believe will improve department performance.

5.Spend as much time as possible talking with and listening to subordinates.

6.Make sure jobs get out on time.

7.Reach out to your boss to discuss her expectations for you and your department.

8.Make sure you set clear expectations and policies for your department.

Scoring and Interpretation: All eight items in the list may be important, but the odd-numbered items are considered more important than the even-numbered items for long-term success as a manager. If you checked three or four of the oddnumbered items, consider yourself ready for a management position. A successful new manager discovers that a lot of time has to be spent in the care and feeding of people, including direct reports and colleagues. People who fail in new management jobs often do so because they have poor working relationships or they misjudge management philosophy or cultural values. Developing good relationships in all directions is typically more important than holding on to old work skills or emphasizing control and task outcomes. Successful outcomes typically will occur when relationships are solid. After a year or so in a managerial role, successful people learn that more than half their time is spent networking and building relationships.

SOURCE: This questionnaire is adapted from research findings reported in Linda A. Hill, Becoming a Manager: How New Managers Master the Challenges of Leadership, 2nd ed. (Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2003); and John J. Gabarro, The Dynamics of Taking Charge (Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 1987).

others —both to reward the individual and to build new talent into the managerial ranks. But making the shift from individual contributor to manager is often tricky. Dianne Baker, an expert nurse who was promoted to supervisor of an out-patient cardiac rehabilitation center, quickly found herself overwhelmed by the challenge of supervising former peers, keeping up with paperwork, and understanding financial and operational issues.15 Baker’s experience is duplicated every day as new managers struggle with the transition to their new jobs. Harvard professor Linda Hill followed a group of 19 managers over the first year of their managerial careers and found that one key to success is to recognize that becoming a manager involves more than learning a new set of skills. Rather, becoming a manager means a profound transformation in the way

See It

See It

Online

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Licensed to: CengageBrain User

|

|

|

What Is It Like to Be a Manager? |

15 |

||

EXHIBIT |

|

|

1.3 |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

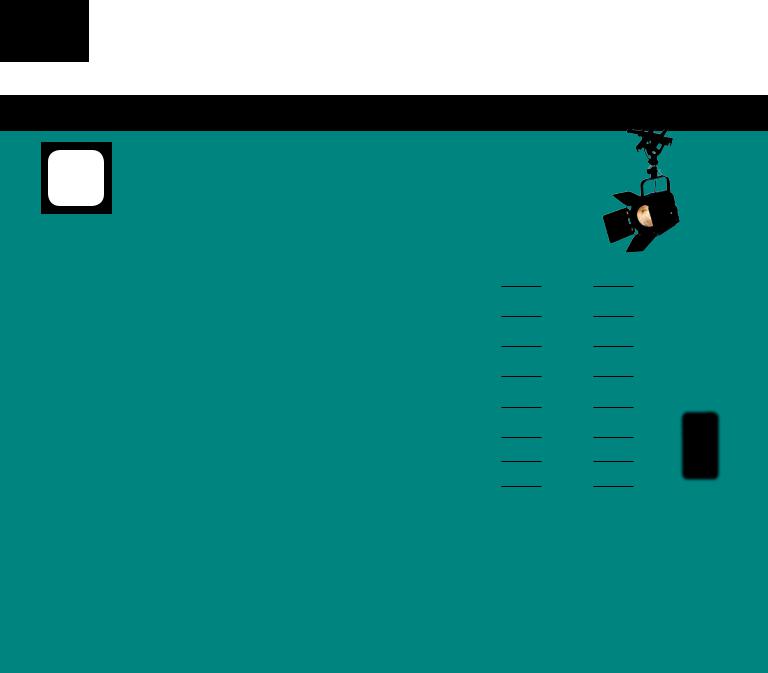

Making the Leap from Individual Performer to Manager |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

From Individual |

|

To Manager |

|

|

|

|

Identity |

|

Identity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Specialist, performs |

|

Generalist, coordinates |

|

|

|

|

specific tasks |

|

diverse tasks |

|

|

|

|

Gets things done |

|

Gets things done |

|

|

|

|

through own efforts |

|

through others |

|

|

|

|

An individual actor |

|

A network builder |

|

|

|

|

Works relatively |

|

Works in highly |

|

|

|

|

independently |

|

interdependent manner |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SOURCE: Based on Exhibit 1.1, “Transformation of Identity,” in Linda A. Hill, Becoming a Manager : Mastery of a New

Identity, 2nd ed. (Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2003), p. 6.

people think of themselves, called personal identity, that includes letting go of deeply held attitudes and habits and learning new ways of thinking.16 Exhibit 1.3 outlines the transformation from individual performer to manager.

Recall our earlier discussion of the role of manager as the person who builds systems rather than doing specific tasks. The individual performer is a specialist and a “doer.” His mind is conditioned to think in terms of performing specific tasks and activities as expertly as possible. The manager, on the other hand, has to be a generalist and learn to coordinate a broad range of activities. Whereas the individual performer strongly identifies with her specific tasks, the manager has to identify with the broader organization and industry.

In addition, the individual performer gets things done mostly through his own efforts, and develops the habit of relying on self rather than others. The manager, though, gets things done through other people. Indeed, one of the most common mistakes new managers make is wanting to do all the work themselves rather than delegating to others and developing others’ abilities.17 For example, when Lisa Drakeman moved from a teaching job at Princeton to being CEO of a biotechnology start-up, she initially went to every meeting, interviewed every job candidate, and read every draft of clinical trial designs. She soon realized that she couldn’t master every detail and that trying to do so would stall the company’s growth. Although it was hard to step back, Drakeman eventually made the transition from doing individual tasks to managing and delegating to others.18

Another problem for many new managers is that they expect to have greater freedom to do what they think is best for the organization. In reality, though, managers find themselves hemmed in by interdependencies. Being a successful manager means thinking in terms of building teams and networks, becoming a motivator and organizer within a highly interdependent system of people and work. Although the distinctions may sound simple in the abstract, they are anything but. In essence, becoming a manager means becoming a new person and viewing oneself in a completely new way.

Can you make a personal transformation from individual performer to manager, accomplishing work by engaging and coordinating other people? Look back at your results on

the “What’s Your Readiness for Management?” questionnaire on page 14 to see how your priorities align with the demands placed on a manager.

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Licensed to: CengageBrain User

16 |

Chapter 1 Innovative Management for a Changing World |

|

|

Many new managers have to make the transformation in a “trial by fire,” learning |

|

|

on the job as they go, but organizations are beginning to be more responsive to the |

|

|

need for new manager training. The cost to organizations of losing good employees |

|

|

who can’t make the transition is greater than the cost of providing training to help new |

|

|

managers cope, learn, and grow. In addition, some of today’s organizations use great |

|

|

care in selecting people for managerial positions, including ensuring that each candidate |

|

|

understands what management involves and really wants to be a manager. A career as a |

|

|

manager can be highly rewarding, but it can also be stressful and frustrating. The Spot- |

|

|

light on Skills titled Do You Really Want to Be a Manager? further examines some of |

|

|

the challenges new managers face. After reading the Spotlight, |

can you answer “yes” to |

|

the question “Do I really want to be a manager?” |

|

Manager Activities

Most new managers are unprepared for the variety of activities managers routinely perform. One of the most interesting findings about managerial activities is how busy managers are and how hectic the average workday can be.

1 Adventures in Multitasking Managerial activity is characterized by variety, fragmentation, and brevity.19 The widespread and voluminous nature of a manager’s involvements leaves little time for quiet reflection. Mintzberg found that the average time a top executive spends on any one activity is less than nine minutes, and another study indicates that some first-line supervisors average one activity every 48 seconds!20

Managers shift gears quickly. Significant crises are interspersed with trivial events in no predictable sequence. Every manager’s job, though in most cases not as potentially dangerous, is similar in its diversity and fragmentation to that of U.S. Marine Corps officers managing the reconstruction efforts in Iraq. Consider the diverse events in a typical day for Capt. Sean Miller in Fallujah, Iraq:21

•Begins the day meeting with tribal sheiks and local officials to decide which projects to finance.

•Drives to a command center to check the status of a job that a contractor has left unfinished.

•Walks to a nearby school to discuss awards for students who recite passages from the Koran.

•Is interrupted by a handful of people who have come with questions or demands: One asks about a relative he says was detained several years ago; another pushes a contract for review into Miller’s hands; a third is seeking work; and so on.

•Finally returns to the discussion of student awards.

•Agrees to a tour of the school, where a contractor explains his request for a $50,000 generator that Miller thinks can be obtained for $8,000.

•Checks the recently cleaned grounds at another school and finds that papers and other trash once again litter the area.

•Notices a man running a pipe from his roof and warns him against running his sewage to the school.

•Calms and directs his marines, some only in their upper teens, who grow as skittish as children and rush from the school building.

•Stops by a café to hear young men’s complaints that they are asked to pay bribes to get a job on the police force.

•Near sunset, takes photos of a still-damaged cemetery door that contractors have been paid to repair.

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Licensed to: CengageBrain User

What Is It Like to Be a Manager? |

17 |

2

© Bata Zivanovic, Shutterstock

Spotlight ON SKILLS

Do You Really Want to Be a Manager?

s management for you? Becoming a manager I is considered by most people to be a positive, forward-looking career move, and indeed life as a manager offers appealing aspects. How-

ever, it also holds many challenges, and not every person will be happy and fulfilled in a management position. Here are some of the issues would-be managers should consider before deciding they want to pursue a management career:

1.The increased workload. It isn’t unusual for managers to work 70 to 80 hours per week, and some work even longer hours. A manager’s job always starts before a shift and ends hours after the shift is over. When Ray Sarnacki was promoted to manager at an aerospace company, he found himself frustrated by the incessant travel, endless paperwork, and crowded meeting schedule. He eventually left the job and found happiness in a position earning about one-fifth of his peak managerial salary.

2.The challenge of supervising former peers. This issue can be one of the toughest for new managers. They frequently struggle to find the right approach, with some trying too hard to remain “one of the gang” and others asserting their authority too harshly. In almost all cases, the transition from a peer-to-peer relationship to a manager-to-subordinate one is challenging and stressful.

3.The headache of responsibility for other people. A lot of people get into management because they like the idea of having power, but the reality is that many managers feel overwhelmed by the responsibility of

hiring, supervising, and disciplining others. New managers are often astonished at the amount of time it takes to handle “people problems.” Kelly Cannell, who quit her

job as a manager, puts it this way: “What’s the big deal [about managing people]? The big deal is that people are human. … To be a good manager, you

have to mentor them, listen to their problems, counsel them, and at the end of the day you still have your own work on your plate. …”

4.Being caught in the middle. Except for those in the top echelons, managers find themselves acting as a backstop, caught between upper management and the workforce. Even when managers disagree with the decisions of top executives, they are responsible for implementing them.

For some people, the frustrations of management aren’t worth it. For others, management is a fulfilling and satisfying career choice and the emotional rewards can be great. One key to being happy as a manager may be carefully evaluating whether you can answer “yes” to the question “Do I really want to be a manager?”

SOUrcEs: Based on information in Henry Mintzberg, Managing (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2009); Erin White, “Learning to Be the Boss,” The Wall Street Journal, November 21, 2005; Jared Sandberg, “Down Over Moving Up: Some New Bosses Find They Hate Their Jobs,” The Wall Street Journal, July 27, 2005; Heath Row, “Is Management for Me? That Is the Question,” Fast Company (February–March 1998), pp. 50–52; Timothy D. Schellhardt, “Want to Be a Manager? Many People Say No, Calling Job Miserable,” The Wall Street Journal, April 4, 1997; and Matt Murray, “Managing Your Career—The Midcareer Crisis: Am I in This Business to Become a Manager?” The Wall Street Journal, July 25, 2000.

Life on Speed Dial The manager performs a great deal of work at an unrelenting pace.22 3 Managers’ work is fast paced and requires great energy. Most top executives routinely work at

least 12 hours a day and spend 50 percent or more of their time traveling.23 Calendars are often booked months in advance, but unexpected disturbances erupt every day. Mintzberg found that the majority of executives’ meetings and other contacts are ad hoc, and even scheduled meetings are typically surrounded by other events such as quick phone calls, scanning of e-mail, or spontaneous encounters. During time away from the office, executives catch up on work-related reading, paperwork, phone calls, and e-mail. Technology, such as e-mail, text messaging, cell phones, and laptops, intensifies the pace. Brett Yormark, the National Basketball Association’s youngest CEO (the New Jersey Nets), typically responds to about 60 messages before he even shaves and dresses for the day, and employees are accustomed to getting messages Yormark has zapped to them in the wee hours of the morning.24

The fast pace of a manager’s job is illustrated by Heather Coin, a Cheesecake Factory manager. Coin arrives at work about 9:30 a.m. and checks the financials for how the restaurant performed the day before. Next comes a staff meeting and various personnel

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Licensed to: CengageBrain User

18 |

Chapter 1 |

Innovative Management for a Changing World |

|

|

duties. Before |

and during the lunch shift, she’s pitching in with whatever needs to be |

|

|

done—making salads in the kitchen, expediting the food, bussing the tables, or talking |

||

|

with guests. After lunch, from 3:00 to 4:30 p.m., Heather takes care of administrative |

||

|

duties, |

paperwork, or meetings with upper management, media, or community organiza- |

|

tions. At 4:30, she holds a shift-change meeting to ensure a smooth transition from the day crew to the night crew. Throughout the day, Heather also mentors staff members, which she considers the most rewarding part of her job. After the evening rush, she usually heads for home about 10 p.m., the end of another 12½-hour day.25

Manager Roles

Mintzberg’s observations and subsequent research indicate that diverse manager activities can be organized into 10 roles.26 A role is a set of expectations for a manager’s behavior. Exhibit 1.4 provides examples of each of the roles, divided into three conceptual

1.4

EXHIBIT

Ten Manager Roles

Category |

Role |

Activity |

|

|

|

Informational |

Monitor |

Seek and receive information, scan |

|

|

periodicals and reports, maintain personal |

|

|

contacts. |

|

Disseminator |

Forward information to other organization |

|

|

members; send memos and reports, make |

|

|

phone calls. |

|

Spokesperson |

Transmit information to outsiders through |

|

|

speeches, reports, memos. |

Interpersonal |

Figurehead |

Perform ceremonial and symbolic duties |

|

|

such as greeting visitors, signing legal |

|

|

documents. |

|

Leader |

Direct and motivate subordinates; |

|

|

train, counsel, and communicate with |

|

|

subordinates. |

|

Liaison |

Maintain information links both inside and |

|

|

outside organization; use e-mail, phone |

|

|

calls, meetings. |

Decisional |

Entrepreneur |

Initiate improvement projects; identify |

|

|

new ideas, delegate idea responsibility to |

|

|

others. |

|

Disturbance handler |

Take corrective action during disputes |

|

|

or crises; resolve conflicts among |

|

|

subordinates; adapt to environmental |

|

|

crises. |

|

Resource allocator |

Decide who gets resources; schedule, |

|

|

budget, set priorities. |

|

Negotiator |

Represent department during negotiation |

|

|

of union contracts, sales, purchases, |

|

|

budgets; represent departmental interests. |

SOURCES: Adapted from Henry Mintzberg, The Nature of Managerial Work (New York: Harper & Row, 1973): 92–93; and Henry Mintzberg, “Managerial Work: Analysis from Observation,” Management Science 18 (1971): B97–B110.

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Licensed to: CengageBrain User

What Is It Like to Be a Manager? |

19 |

© Kuzmik, Shutterstock

Benchmarking

Artisan Ice Cream

hen Ben Van Leeuwen drove a Good humor W truck in college, little did he know it would become the model for his new business venture, which he started two years after graduation. An

admitted Foodie with a lifelong obsession with food, Ben was also obsessed with locally grown and sustainable ingredients. Wanting to get the right people on the bus (literally), he recruited his future wife, Laura O’Neill and his brother, Pete, to help him sell ultra-premium quality ice cream out of a truck in Brooklyn. From his college job, Ben had learned that funding a truck is a lot cheaper than a storefront.

Using a 60-page business plan he had completed in a college course, he was able to secure $80,000 in funding from family and friends. First, they bought a $5,000 truck on eBay and added a freezer, plumbing, a generator, and huge windows, plus chrome grilles and a butter-yellow coat of paint, to give the feel of old-fashioned ice cream. Ben’s fiancée developed a handwritten menu. Total cost: $45,000.

Their next hurdle was finding a manufacturer. No supplier made ice cream in the quality they wanted. After months of tedious recipe testing, they found the formula but knew they did not have the capital to build a factory. Finally, they were able to get a contract in upstate New York with Mercer’s Dairy, whose first run of 500 gallons cost $8,000.

One day after Ben and Laura were married in summer of 2008, they drove their truck to a New York City street fair and sold 500 scoops. Fortu-

itously, one of them was to a Whole

Foods manager, who later helped them stock their products at his store. They made some mistakes but learned quickly that if you have the freezer temperature even two degrees too low, you can’t scoop. The three founders and one hired helper worked around the clock that first summer. In between the scooping was fixing the unreliable truck and strategizing on which corners to set up each morning.

Reaching out to social marketing, they managed to get one influential blogger, Gothamist, to give a great review, calling their product, “a taste of creamy ecstasy.”

Revenues the first year were $425,000, with $125,000 of that profit. By 2009, they added two more trucks and sales soared to $900,000. Most of the profits have gone back into building the business. During the colder months, they’ve branched out into high-end coffee and pastries and have a goal of $2 in revenue. What a sweet life.

SOUrcE: Kimberly Weisul, “Spurred by a passion for gourmet grub, Ben Van Leeuwen launched a fleet of truck offering a “taste of creamy ecstasy,” INC Magazine, October 2010, p. 66.

categories: informational (managing by information), interpersonal (managing through people), and decisional (managing through action). Each role represents activities that managers undertake to ultimately accomplish the functions of planning, organizing, leading,

and controlling. Although it is necessary to separate the components of the manager’s job to understand the different roles and activities of a manager, it is important to remember that the real job of management cannot be practiced as a set of independent parts; all the roles interact in the real world of management.

Ben Van Leeuwen used both the Entreprenuerial role, as well as those of Spokesperson (through social media) and Resource Allocator in starting his premium ice-cream business, as described in the Benchmarking box.

•Becoming a new manager requires a shift in thinking from individual performer to an interdependent role of coordinating and developing others.

•Because of the interdependent nature of management, new managers often have less freedom and control than they expect to have.

•The job of a manager is highly diverse and fast paced.

•A role is a set of expectations for one’s behavior.

•Managers at every level perform ten roles, which are grouped into informational roles, interpersonal roles, and decisional roles.

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.