Approches_Eco_Anal_Cours_2013

.pdf

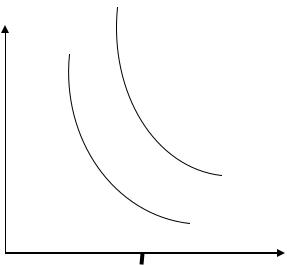

B

A

inflation

unemployment

un (natural rate of unemployment)

The curve A is the Phillips curve when the expected inflation is low while on the curve B the expected inflation is high. People adjust their expectations of inflation over time, the trade-off between inflation and unemployment holds only in the short run. Then, it is assumed that policymaker cannot keep inflation above expected inflation forever. In this theoretical framework, the classical dichotomy holds in the long run, unemployment returns to its natural rate and there is no trade-off between inflation and unemployment.

* Disinflation and the sacrifice ratio

Imagine an economy in which unemployment is at its natural rate and inflation is running at 10 percent. What would happen to unemployment and output if the central bank pursued a policy to reduce inflation from 10 to 4 percent? The Philips curve shows that, in the absence of a beneficial supply shock, lowering inflation requires a period of high unemployment and reduced output. But by how much and for how long would unemployment need to rise above the natural rate? Before deciding whether to reduce inflation, policymakers must know how much output would be lost during the transition to lower inflation. This cost can then be compared with the benefits of lower inflation.

Much research has used the available data to examine the Philips curve quantitatively. The results of these studies are often summarized in a number called the sacrifice ratio, the percentage of a year’s real GDP that must be forgone

79

to reduce inflation by 1 percentage point. Although estimates of the sacrifice ratio vary substantially, a typical estimate is that for every percentage point that inflation is to fall, 5 percent of one year’s GDP must be sacrificed.

We can also express the sacrifice ratio in terms of unemployment. Okun’s law says that a change of 1 percentage point in the unemployment rate translates into a change of 2 percentage points in GDP. Therefore, reducing inflation by 1 percentage point requires about 2.5 percentage points of cyclical unemployment.

We can use the sacrifice ratio to estimate by how much and for how long unemployment must rise to reduce inflation. Since reducing inflation by 1 percentage point requires a sacrifice of 5 percent of a year’s GDP, reducing inflation by 6 percentage points requires a sacrifice of 30 percent of a year’s GDP. Equivalently, this reduction in inflation requires a sacrifice of 15 percentage points of cyclical unemployment. This disinflation could take various forms, each totalling the same sacrifice of 30 percent of a year’s GDP. For example, a rapid disinflation would lower output by 15 percent for two years: this is sometimes called the cold turkey solution to inflation. A moderate disinflation would lower output by 7,5 percent for four years. An even more gradual disinflation would depress output by 3 percent for a decade.

* Rational expectations and painless disinflation

Because the expectation of inflation influences the short-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment, a crucial question is how people form expectations. So far, we have been assuming that expected inflation depends on recently observed inflation. Although this assumption of adaptive expectations is plausible, it is probably too simple to be applicable in all circumstances.

An approach called rational expectations assumes that people optimally use all the available information, including information about current policies, to forecast the future. Because monetary and fiscal policies influence inflation, expected inflation should also depend on the monetary and fiscal policies in effect. According to the theory of rational expectations, a change in monetary or fiscal policy will change expectations, and an evaluation of any policy change must incorporate this effect on expectations. This approach implies that inflation is less inertial than it first appears.

80

The rational expectations’ models argue that the short-run Philips curve does not accurately represented the options available. They believe that if policymakers are credibly committed to reducing inflation, rational people will understand the commitment and quickly lowered their expectations of inflation. According to the theory of rational expectations, traditional estimates of the sacrifice ratio are not useful for evaluating the impact of alternative policies. Under a credible policy, the costs of reducing inflation may be much lower than estimates of the sacrifice ratio suggest. Nowadays, this credibility is assumed to be reached more easily if the central bank is independent from the government and can take its monetary decisions without any political considerations. That is why it is asserted that a conservative monetary policy, consisting in only anti-inflationary monetary policy, is the best way to stabilize the inflationary expectations of economic agents.

In the most extreme case, one can imagine reducing the rate of inflation without causing any recession at all. A painless disinflation has two requirements. First, the plan to reduce inflation must be announced before the workers and firms who set wages and prices have formed their expectations. Second, the workers and firms must believe the announcement; otherwise, they will not reduce their expectations of inflation. If both requirements are met, the announcement will immediately shift the short-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment downward, permitting a lower rate of inflation without higher unemployment.

In fact, these assertions follow the monetarist and the New Classical neutral-money view: The central bank’s actions and the monetary policy should be developed and implemented outside the political considerations. The coherence and the relevance of monetary policies, when the markets are assumed to contain spontaneous equilibrating mechanisms, imply an independent central bank. This independence should insure the setting of a serious monetary policy which consists in striking against inflation. This criterion gives a conservative central bank adopting anti-inflationist policies such that economic agents with rational expectations could have confidence in central bank’s announcements.

Consequently, good monetary policy is the one that set on the rules that allow central bank to be credible, thus a consensus is established, in the literature, on the need for the central bank to be conservative.

81

Although the rational expectations approach remains controversial, almost all economists agree that expectations of inflation influence the short-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment. The credibility of a policy to reduce inflation is therefore one determinant of how costly the policy will be. Unfortunately, it is often difficult to predict whether the public will view the announcement of a new policy as credible. The central role of expectations makes forecasting the results of alternative policies far more difficult.

2. Business Cycles and market imperfections

2. 1. Real Business Cycle theory

Consider now a model of fluctuations. The new feature of the model is the behaviour of labour supply. In the classical model discussed so far, the supply of labour is fixed and it determines the level of employment. Yet employment fluctuates substantially over the business cycle. If we want to maintain the classical assumption that the labour market clears, as new classical economists do, then we must examine what causes fluctuations in the quantity of labour supplied.

The supply of goods and services depends in part on the supply of labour. The greater the number of hours people are willing to work, the more output the economy can produce. Real-business-cycle theory emphasizes that the quantity of labour supplied at any point in time depends on the incentives that workers face. When workers are well rewarded, they are willing to work more hours; when the rewards are less, they are willing to work fewer hours. Sometimes, if the reward for working is sufficiently small, workers choose to forgo working altogether -at least temporarily. This willingness to reallocate hours of work over time is called the inter-temporal substitution of labour. According to real business cycle theory, all workers perform the cost-benefit analysis to decide when to work and when to enjoy leisure. If the wage is temporarily high, the supply of labour will be high, if the wage is low, the leisure will be high. This theory uses this inter-temporal substitution of labour to explain why employment and output fluctuate. Shocks to the economy that cause the wage to be temporarily high push people to want to work more. This increase in work effort raises employment and production.

82

Many real business cycle theorists emphasize also the role of shocks to technology. Suppose, for instance, that an innovation (or an invention) modifies the production process of the economy. According to real business cycle theory, this change should affect the economy in two ways.

First, the improved technology increases the supply of goods and services. Because the production is improved, more output is produced and the real aggregate supply curve shifts outward.

Second, the availability of the new technology raises the demand for goods. For example, firms wishing to acquire this technology, in order to improve their production conditions or their competitive positions on markets, will raise their demand for investment goods. Then, the real aggregate demand curve shifts outward. The shift in the real aggregate supply curve can be more or les than the shift in the real aggregate demand curve depending on various factors that will not be studied here:

Interest |

Real aggregate |

rate |

supply |

i2

i1

Real aggregate demand

Income, output

Y1  Y2

Y2

The output will shift from Y1 to Y2 (growth) while the interest rate will rise from i1 to i2, the bold curves representing the new data with the new technology.

83

Real business cycle theory assumes that the fluctuations in technology (modifying the ability of the economy to turn inputs, as capital and labour, into output, as goods and services) generate fluctuations in output and employment. Consequently, this theory explains recessions as periods of technological regress while critics argue that technological regress is implausible because the accumulation of technological knowledge may slow down, but it would never go in reverse.

2. 2. Supply-side economics

The supply-side economics is closely associated with some policy prescriptions emphasizing that tax rates should be lowered in order to improve growth and economic activity.

The type of analysis employed is standard neoclassical economics, and this analysis is used to study the macroeconomic incentive effects of taxation. The supply-side economics are used to describe the application of neoclassical analysis to this issue in order to distinguish the resulting models from others, notably the Keynesian ones, in which the macroeconomic effects of fiscal policy operate largely through income rather than substitution effects. This stream is influenced by a set of ideas common at the University of Chicago, that people respond to incentives, that the resulting substitution effects can frequently be larger than is generally believed, and that government’s behaviour can have an important effect on private incentives.

The main propositions developed by this analysis are:

1)There exists a trade-off between taxes on labour and capital necessary to maintain a given level of output;

2)There exists a tax structure that maximizes government revenue;

3)There exists a tax structure that maximizes output at a given level of government revenue;

4)There exists a tax structure that maximizes welfare at a given level of government revenue.

The supply-side models try to show that if the tax structure is such that either tax rate is in the prohibitive range, then there exists another tax structure

84

that yields the same revenues for the government but higher output and welfare. In a monetarist-quantity vein, these models remark, under specific hypotheses, that a permanent increase in the monetary base causes a permanent equiproportional increase in nominal income but no permanent change in real income. And, following the Real expectations models, they state that a permanent increase in government debt causes a permanent increase in nominal income but no permanent change in real income.

More specifically, the supply-side models assert that a permanent increase in marginal tax rates on income from labour or capital has no effect on nominal income, but causes a permanent reduction in real income. For the tax on income from capital, this effect may be so strong that the increase in tax rates would well reduce government revenue.

Supply-side economics provide a framework of analysis which relies on personal and private incentives. When incentives change, people’s behaviours change in response. People are assumed to be attracted toward positive incentives and repelled by the negative. The role of government in such a framework is carried out by the ability of government to alter incentives and thereby affect society’s behaviour. In its most basic form, if an action is taken that makes an activity more attractive people will do more of that activity. If, on the other hand, government actions (for instance, repressive fiscal policies) make an activity less attractive, people will shun or otherwise avoid this activity. Subsidies and taxes are the means by which government can positively or negatively alter incentives.

In order to state these assertions, economists use usually the following

figure:

85

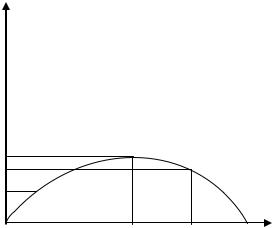

Fig. Government’s fiscal revenue as a function of the tax rate

Government’s fiscal revenue, T

M

C

A

The applied tax rate, t

B

This figure is based on the idea that there is a maximum tax rate (the optimal rate) at which the fiscal revenue of the government is maximized (the point M). At A, the tax rate is low and government can raise it in order to increase its revenue without reducing economic activity’s level. When the tax rate is over the optimal point, M, the rise of the tax, for instance, at the point B, will lower its revenue because the level of the taxation will be too high for individuals to undertake a sufficient level of activity. The net return on economic activity for enterprises (or for labour suppliers) will be too low. The incentives are negatively altered by the government fiscal policy. The level of economic activity will be low and the tax revenues of the government will decline at C (with C<M). This curve is called the Laffer curve (see Canto et al. 1983).

3. Optimal economic policies: Conduct by rule or by discretion?

Another fundamental topic of debate among economists is whether economic policy should be conducted by rule or by discretion. Policy is conducted by rule if policymakers announce in advance how policy will respond to various situations and commit themselves to following through on this announcement. Policy is conducted by discretion if policymakers are free to size up the situation case by case and chose whatever policy seems appropriate at the time.

86

The debate over rules versus discretion is distinct from the debate over passive versus active policy. Policy can be conducted by a rule and yet be either passive or active. For example, a passive policy rule might specify steady growth in the money supply of 3 percent per year. An active policy rule might specify that:

Money Growth=3%+(Unemployment Rate-6%).

Under this rule, the money supply grows at 3 percent if the unemployment rate is 6 percent, but for every percentage point the unemployment rate exceeds 6 percent, money growth increases by an extra percentage point. This rule tries to stabilize the economy by raising money growth when the economy is in a recession.

3. 1. The time inconsistency of discretionary policy and policy rules

Some economists believe that economic policy is too important to be left to the discretion of policymakers. Although this view is more political than economic, evaluating it is central to how we judge the role of economic policy. If politicians are incompetent or opportunistic, then we may not to give them the discretion to use the powerful tools of monetary and fiscal policy.

Incompetence in economic policy arises for several reasons. Some economists view the political process as erratic, perhaps because it reflects the shifting power of special interest groups. In addition, macroeconomics is complicated, and politicians often do not have sufficient knowledge of it to make informed judgments. This ignorance allows sometimes some policymakers to propose incorrect but superficially appealing solutions to complex problems.

Opportunism in economic policy arises when the objectives of policymakers conflict with the well-being of the public. Some economists fear that politicians use macroeconomic policy to further their own electoral ends. If citizens vote on the basis of economic conditions prevailing at the time of the election, then politicians have an incentive to pursue policies that will make the economy look good during election years. A president might cause a recession soon after coming into office in order to lower inflation and then stimulate the economy as the next election approaches to lower unemployment; this would ensure that both inflation and unemployment are low on election day. Manipulation of the economy for electoral

87

gain, called the political business cycle, has been the subject of extensive research by economists and political scientists.

Distrust of the political process leads some economists to advocate constitutional amendments, such as a balanced-budget amendment, that would tie the hands of legislators and insulate the economy from both incompetence and opportunism.

If we assume that we can trust our policymakers, discretion at first glance appears superior to a fixed policy rule. Discretionary policy is, by its nature, flexible. As long as policymakers are intelligent and benevolent, there might appear to be little reason to deny them flexibility in responding to changing conditions.

Yet a case for rules over discretion arises from the problem of time inconsistency of policy. In some situations policymakers may want to announce in advance the policy they will follow in order to influence the expectations of private decision-makers. But later, after the private decision-makers have acted on the basis of their expectations, these policymakers may be tempted to renege on their announcement. Understanding that policymakers may be inconsistent over time, private decision-makers are led to distrust policy announcements. In this situation, to make their announcements credible, policymakers want to make a commitment to a fixed policy rule.

Following Mankiw (1994), we can illustrate the time inconsistency in an example involving not economics but politics-specifically, public policy about negotiating with terrorists over the release of hostages. The announced policy of most nations is that they will not negotiate over hostages. Such an announcement is intended to deter terrorists: if there is nothing to be gained from kidnapping hostages, rational terrorist won’t kidnap any. In other words, the purpose of the announcement is to influence the expectations of terrorists and thereby their behaviour.

But, in fact, unless the policymakers are credibly committed to the policy, the announcement has little effect. Terrorists know that once hostages are taken, the temptation to make some concession to obtain their release can be overwhelming. The only way to deter rational terrorists is somehow to take away

88