Approches_Eco_Anal_Cours_2013

.pdfIn the Keynesian schema, for a given state of expectations (animal spirits), r decreases as I increases. In order to determine the amount of I, we have to know the interest rate, i, which is supposed to be an indicator of the cost of financing I.

But Rt are not concrete but psychological variables depending on entrepreneurial animal spirits, depending themselves on the state of confidence about the expected evolution of the economic system. For a given level of i, I decreases as entrepreneurs’ confidence worsens.

3. The liquidity preference

In the neoclassical theory, the interest rate equalizes savings and investments. i is a real variable that depends on the gap between S and I on markets.

The quantity equation of exchange defines the amount of money (M) that individuals wish to hold as proportional to nominal national income (PY, where is the price level and Y the real income):

MV = PY

(where V is the velocity).

After the formulation of money demand used by economists at Cambridge University ( in Great Britain) in the early twentieth century, the inverse of velocity, k=(1/v), is used to identify the Cambridge equation:

M=kPY.

Then, the quantity theory is formulated in terms of the quantity of liquid balances which individuals wish to keep in relation to the real income they earn. Consequently, money is demanded for its services in the purchasing of goods. As purchases are not completely planned, liquid reserves are required as transactionary and precautionary stock. Individuals had liquid assets because of the uncertain future.

In this view, money is the liquid asset hold by individuals. But money is also necessary to finance investment. The entrepreneurs, in order to finance their investment expenditure, issue form of liabilities (bonds, bills of exchange, bank debts) that they sell in exchange for money. The buyers of these forms of liabilities

69

renounce holding money and hold non-liquid assets. Therefore, the demand for money depends not only on the level of transactions, as in the Cambridge equation, but also on the level of the interest rate which gives the liquidity premium allowing agents to part with their money balances.

For a given liquidity preference, the quantity of money that economic agents decide to hold increases as the interest rate decreases. So, if the monetary authorities manage to control the money supply, they will try to affect the interest rate. Monetary policy could act on the real economy by the Keynesian indirect transmission mechanism. An expansion in the money supply increases the price of securities (forms of liabilities exchanged on markets) and decreases the interest rate. Then, given the schedule of marginal efficiency of capital, this decrease of the interest rate (hence, of the cost of financing of investments) induces an increase in I. By the multiplier relation, the income and the employment must increase.

However, those so-called Keynesian mechanics are criticised by some post Keynesians from the 70s. Keynes himself became very sceptical at the end of the 30s about this mechanism of the effectiveness of monetary policy. We have some explanations which can show the limits of this mechanism.

On one hand, the mechanism depends on the assumption that the quantity of money is fixed exogenously by the monetary authorities. If this is not true and if the quantity of money is endogenous (determined by the monetary-financing needs of economic agents), the authorities are not able anymore to control the money supply. This is the view depended nowadays by the Post Keynesian theory.

On the other hand, we have to remark that money is demanded also to finance speculation. The speculators, by selling or buying securities with the intention of realizing speculative gains, contribute to modifying the stock market variables. In abnormal times, speculators do not take into account the fundamental values, but try to make capital gains with a very short-run perspective. This kind of behaviour destabilises the market and reduces the effectiveness of monetary policies which aim to setting the interest rate in a discretionary way. The objectives of monetary policy are frustrated by speculators’ expectations.

70

Moreover, even if we agree with the assertion that the monetary authorities are able to set the interest rate, we cannot know in what degree a variation in the interest rate level would influence the investment decisions of economic agents. If profit expectations basically depend on the moods of the entrepreneurs which are very unstable and subjective, as Keynes seems to believe, then changes of the interest rate could not modify themselves the entrepreneurial expectations about the future state of affairs. There is an inertia that makes the expectations difficult to modify solely by interest rate changes in the short-run.

The Keynesian theory tries to point out the difficulties of functioning of a market economy at a given equilibrium point. The market economy’s evolution is a consequence of private economic agents’ decisions. These decisions are decentralized and depend on some uncontrollable subjective factors. The state interventions are viewed as necessary in order to orient the decisions towards a collectively viable economic situation. Keynes was not a opponent of the liberal economy, he believed that State interventions should not abolish the market economy but help it to manifest itself and render it viable. The idea of administered market economy has to be understood by this way. That is the core of the Keynesian economics.

71

Chapter IV: From Neoclassical macroeconomics to New Keynesian Critiques

1. Monetarism and the New Classical economics

1. 1. Monetarism as the revival of the quantity theory of money

The monetarist theory is the Milton Friedman’s reworking of the traditional quantity theory of money, in conflict with the Keynesian economics. This monetarist counter-revolution began in 1956, when Friedman published The Quantity Theory of Money (see The Optimum Quantity of Money and Other Essays, 1970, Macmillan).

Friedman interprets the quantity theory as a theory of demand for money. He included among the arguments of money demand function the interest rates on bonds and shares and the inflation rate (interpreted as a negative rate of returns on liquid assets), as well as wealth and other structural and institutional variables. Friedman asserted that the money demand function is a stable function founded on a stable velocity of money circulation which he renamed the monetary multiplier. He suggested also that consumption depends on permanent income (incomes received in past years besides that of the current year), the propensity to consume calculated on permanent income. Moreover, current income always contains a transitory component which is random and variable.

Therefore, the propensity to consume and the Keynesian multiplier are not only low but change markedly in response to changes in income-level. He concluded that impulses from fiscal policy, through the Keynesian multiplier, are less effective than monetary stimuli. The crowding-out thesis comes to reinforce these assertions. Given the money supply, an increase in public spending financed by barrowing will increase the rate of interest, and consequently crowd out private investments, so that aggregate demand will not increase. On the contrary, given public spending, a rise in the money supply will increase incomes, without raising the interest rate.

72

Friedman stated that the influence of the money supply is strong but irregular, the delay occurring between the monetary impulse and the real effects being long and variable. Even though money is able to disturb the real economy, owing to the unpredictable nature of its real effects, nobody would be able to use it as an instrument of discretionary policy.

Founded on the quantity causality, the monetarist position argues that the inflation is a monetary phenomenon, the level of prices depending on money supply, given exogenously by the monetary authorities:

MV = PT

If T (transactions) and V (velocity) are stable variables depending on the habits of economic agents (at the equilibrium agents have no reason to change their position) and if relative prices are determined by the real market forces (supply and demand of real goods giving an equilibrium price vector as in the neoclassical theory), therefore all changes in the price level P are due to the changes of M:

P M

The conclusion is obvious: the best thing to do for monetary policy is to increase the money supply according to the level of long-run real growth and to let the market forces deal with short-run adjustments in order to establish spontaneously the level of long-run equilibrium-real-variables.

The effects of the monetary policies are supposed to be depending on the short-run expectations errors of agents. In the short-run, there can be a monetary illusion. Given certain inflationary expectations, authorities are able to reduce the level of unemployment only if they increase the money supply in such a way as to generate an inflation rate which is greater than the expected one. Thus the entrepreneurs believe in a reduction in the level wage and increase the demand for labour. The money wage will increase and the workers increase their supply of labour believing that their wage is raised. However, individuals are not fooled for long. When they understand that the prices have risen more than predicted, they will raise their expectations on the inflation rate and will realize that the real wage level is not more than the previous level. The will workers reduce the labour supply and the unemployment level will rise and return to its precedent level. This level,

73

which is called the natural rate of unemployment (when the real variables are at their equilibrium level), cannot be modified at the long-run, by monetary policy. At the short-run the monetary policy can affect the unemployment level by fooling the agents’ expectations but it is without real influence in the long-run. The sole effect of this policy consists in raising the level of inflation.

The complete analysis of this theoretical view is given by the Phillips curve.

1. 2. Phillips curve, natural rate of employment and the rational expectations

The main goals of economic policymakers are low inflation and low unemployment. The Phillips curve examines the relationship between inflation and unemployment. This curve shows the short-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment.

* The Phillips curve

The Philips curve is merely another way to express aggregate supply. The short-run aggregate supply curve shows a positive relationship between the price level and output. Output deviates from the natural rate ( Y ) when the price level deviates from the expected price level ( Pe ):

Price level, P

Y= Y (P Pe)

Short-run aggregate supply

Pe

Income, output, Y

Y

Since inflation is the rate of change in the price level, and since unemployment fluctuates inversely with output, the aggregate supply curve implies a negative

74

relationship between inflation and unemployment. The Phillips curve expresses this negative relationship.

The Phillips curve posits that the inflation rate -the percentage change in the price leveldepends on three forces:

1.Expected inflation

2.The deviation of unemployment from the natural rate, called cyclical unemployment

3.Supply shocks

These forces are expressed in the following equation:

= e – β(u-un)+ ε

Where is the inflation, e the expected inflation, (u-un) the cyclical unemployment and ε the supply shock (with a parameter β >0). High unemployment tends to reduce inflation because when the unemployment increases, it is assumed that the wages are decreasing. Then the original Phillips curve indicates the inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment:

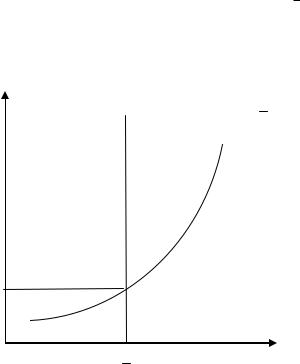

The

rate

of The original Phillips curve

inflati on,

Unemployment, u

To see that the Philips curve and the aggregate supply curve express essentially the same relationship, write the aggregate supply equation as:

75

P Pe 1 (Y Y ) .

Now, subtract last year’s price level, P-1 from both sides of this equation to obtain:

(P P1) (Pe P1) 1 (Y Y).

The left-hand side’s term is the difference between the current price level and the last year’s price level, which is the inflation, (usually, the inflation is given as a rate of evolution of the price level within a given period, say a year. Therefore, in order to calculate the rate of inflation, one should calculate the following expression: [(P P 1) / P 1].100, which gives theinflation rate as a percentage . ). The first term on the right-hand side is the difference between the expected price level and last year’s price level, which is the expected inflation ( e). Therefore, we can write as:

= e+ 1 (Y Y ).

Following the Okun’s law, we can state that the deviation of output from its natural rate is inversely related to the deviation of unemployment from its natural rate its equilibrium rate); that is, when output is higher than the natural rate of output, unemployment is lower than the natural rate of unemployment. Using this

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

relationship, we can substitute –β(u-un) for |

(Y Y ). |

Then our equation |

||||

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||

becomes: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

= e–β(u-un).

Add now a supply shock, , to represent exogenous influences on prices, such as a change in oil prices, a change in the minimum wage, or the imposition of government controls on prices:

= e–β(u-un)+ .

Thus, we obtain the Phillips curve from the aggregate supply equation. Notice that the Philips curve retains the key feature of the short-run aggregate supply curve: a link between real and nominal variables that causes the classical

76

dichotomy to fail. More precisely, the Philips curve demonstrates the connection between real economic activity and unexpected changes in the price level.

* Expectations and Inflation Inertia

To make the Philips curve useful for analyzing the choices facing policymakers, we need to say what determines expected inflations. A simple and often plausible assumption is that people form their expectations of inflation based on recently observed inflation. This assumption is called adaptive expectations. For example, suppose that people expect prices will rise this year at the same rate they did last year. Then:

e= _1

In this case, we can write the Philips curve as:

e= _1- β(u-un)+ ,

this states that inflation depends on past inflation, cyclical unemployment, and a supply shock.

The first term in this form of the Philips curve, _1, implies that inflation is inertial. If unemployment is at its natural rate and if there are no supply shocks, prices will continue to rise at the prevailing rate of inflation. This inertia arises because past inflation influences expectations of future inflation and because these expectations influence the wages and prices that people set. Robert Solow captured the concept of inflation inertia well when, during the high inflation of the

1970s, he wrote, “Why is our money ever less valuable? Perhaps it is simply that we have inflation because we expect inflation, and we expect inflation because we’ve had it?” (quoted in Mankiw, 1994, p. 305). If prices have been rising quickly, people will expect them to continue to rise quickly. Because the position of the short-run aggregate supply curve depends on the expected price level, the shortrun aggregate supply curve will shift upward over time. It will continue to shift upward until some event, such as a recession or a supply shock, changes inflation and thereby changes expectations of inflation.

The aggregate demand curve must also be shifting upward in order to confirm the expectations of inflation. Most often, the continued rise in aggregate demand is due to persistent growth in the money supply. If the central bank

77

suddenly halted money growth, aggregate demand would stabilize, and the upward shift in aggregate supply would cause a recession. The high unemployment in the recession would reduce inflation and expected inflation, causing inflation inertia to subside.

The second and third terms in the Philips curve show the two forces that can change the rate of inflation. The second term, β(u-un), shows that the deviation of unemployment from its natural rate exerts upward or downward pressure of inflation. Low unemployment pulls the inflation rate up. This is called demand-pull inflation because high aggregate demand is responsible for this type of inflation. High unemployment pulls the inflation rate down. The parameter β measures how responsive inflation is to cyclical unemployment. The third term, , shows that inflation also rises and falls because of supply shocks. An adverse supply shock, such as the rise in world oil prices in the 1970s, implies a positive value of and causes inflation to rise. This is called cost-push inflation because adverse supply shocks are typically events that push up the costs of production. A beneficial supply shock, such as the oil glut that led to a fall in oil prices in the 1980s implies a negative value of and causes inflation to fall.

* The short-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment

The relation underlined by the Philips curve gives some option to policymaker who can influence aggregate demand with monetary or fiscal policy. At any moment, expected inflation and supply shocks are beyond the policymaker’s immediate control. Yet, by changing aggregate demand, the policymaker can alter output, unemployment, and inflation. The policymaker can expand aggregate demand to lower unemployment and raise inflation, or he can depress aggregate demand to raise unemployment and lower inflation.

The policymaker can manipulate aggregate demand to choose a combination of inflation and unemployment on this curve, called the short-run Philips curve. However, one should notice that the short-run Philips curve depends on expected inflation. If expected inflation rises, the curve shifts upward, and the policymaker’s trade-off becomes less favourable: inflation is higher for any level of unemployment:

78