Approches_Eco_Anal_Cours_2013

.pdf3)The opportunity cost which suggest that the costs which influence decisions are reducible to the most important of the sacrificed alternatives when productive resources are employed for a certain aim.

4)The time dimension in both consumption and production activities from which the notion of time preference is derived and the hypothesis of a greater productivity of the less direct methods of production.

4.2. From marginalist theory of distribution to the Wicksellian monetary theory

As a great figure of the Sweedish School, Wicksell published two seminal books, Geldzins und Güterpreise (Monetary Interest and Prices of Goods, 1898) and Lectures on Political Economy (1936). Wicksell’s contribution to the marginalist theory of distribution is really important. Wicksell used a simple general equilibrium model with only one good, Q, produced by the means of labour, L, and homogenous capital, K. About the problem of exhaustion of the product, Wicksell integrated the argument that in order to obtain the exhaustion it is sufficient for firms to activate production up to the attainment of minimum average costs. Only at the point of long-run minimum cost it is to have zero profits.

Wicksell’s solution is based on the theory of the entrepreneur, according to which the entrepreneur contributes to the production process by means of the services of his own factors. In equilibrium these services have the same remuneration, whether they are employed by the entrepreneur in his own firm or passed on to the other firms. The labour employed to organize and coordinate the firm will be remunerated in the same way exactly as the labour of the same quality employed in other organizational tasks and nobody would wish to be a subordinate.

We remark that in order to make profits zero, the number of those who possess entrepreneurial skills must be high. It appears from this condition that Wicksell had in mind, even if he did not say to himself, a stationary-state equilibrium in which the entrepreneur has no real decision-making role, and which the organizational work is reduced to mere supervision.

Concerning the money and the variations in the rule of money, Wicksell, including bank credit and the entrepreneurs’ production decisions, advanced that

59

in the absence of exogenous disturbances (those over which the central bank has no control, such as variations in the production of gold or the necessity to finance huge government deficits), the fluctuations in the price level would be caused by a persistent gap between the bank (or market) rate of interest and the real (or natural) rate which is defined as the expected rate of returns on nearly produced capital goods. Wicksell came to the conclusion that, contrary to the implication of the simple quantity theory, it is the quantity of money that adjusts to the price-level movements.

In this analysis, monetary equilibrium requires the satisfaction of three conditions:

1)Equality between the natural and the bank rate of interest;

2)Equality between the supply of savings and the demand for investment loans and real cash balances;

3)Price stability,

The first condition states that in a credit economy, banks can create money credit in order to finance the investment plans of entrepreneurs allowing them to avoid the preliminary saving constraint. This possibility separates the available savings and the demand for investment loans. The consequence of this, in Wicksellian approach, is a monetary disequilibrium. In order to establish the equilibrium we have therefore to satisfy the two first conditions.

4. 3. Utility: cardinalism or ordinalism?

The foundation of the ordinalist statute of the utility and the fundamental criterion of optimality are mainly due to Pareto’s works. His Cours d’Economie

Politique (1896-97) and his Manuela di economica politica (1906) are the most popular contributions of Vilfredo Pareto to economics.

The corner-stone of the construction of the Pareto is the theory of rational consumer behaviour. The first law of Gossen says that if an enjoyment is experienced uninterruptedly, the corresponding intensity of pleasure decreases continuously until satiety is ultimately reached, at which point the intensity becomes nil. After having defined the utility of a good as its ability to satisfy needs, the early marginalists postulated the existence of a function that associates a

60

measure of total utility with the quantities of goods. It is also assumed that the increment in utility corresponding to each extra quantity consumed gradually decreases (decreasing marginal utility). This is based on the assumption that the utility an individual derives from the consumption of a good is a quantity that can be measured cardinally-a value which is unique in a regard to linear transformation. Because the utility is defined as the intrinsic quality of objects (the property of generating happiness by satisfying needs), the utility that goods would possess is defined as an intrinsic property. Happiness and welfare are objective, just as the health of a person is not subjective, as with the pleasure received from eating a good meal! The utility is thought as it could be treated in the same way as weight is.

In his Cours, Pareto used the terms “ophelimity” denoting the attribute of a thing capable of satisfying a need or a desire, legitimate or not. The utility becomes thus expression of preferences (individual choices). Pareto makes a distinction between ophelimity, as the property of an object desired by an individual and the utility, as the property of an object which is beneficial to society.

Air and light, useful to the human race, do not give ophelimity. “Unpleasant medicine is useful for the patient, but does not bring him ophelimity” (Screpanti and Zamagni, 1995, p. 205). The Pareto’s terminological innovation is founded on the difference between what is socially useful (utility) and what is individually (subjectively) desired (ophelimity). Pareto thought that the question whether utility or ophelimity are measurable is irrelevant. He showed that it is possible to assign arbitrary indexes to the indifference curves (of utility). However, he continued to consider ophelimity as cardinally measurable.

On one hand, utility only referred to the preference ordering of the individual, on the other hand, preferences were defined with respect to a situation of choice. Ordinal utility and cardinal utility present themselves as two distinct but central notions in economies.

4. 4. Pareto optimality and welfare economics

Once the notion of cardinal utility had been abandoned it became obvious that there is no reason of making interpersonal comparison of utility. Therefore the

61

question arises that how is it possible to make judgments on alternative policy measures and economic situations.

The criterion arose from the Pareto’s approach is: the efficiency of an allocation is maximal when it is impossible to increase one economic magnitude without decreasing another. In other terms, a certain economic configuration is optimal when it is impossible to increase the welfare of an individual without decreasing that of another. We do not need use comparisons among individuals’ utilities.

The application of this criterion to the Walrasian theory is obvious and will be suggested by G. Debreu in the second half of the 20th century: when all goods are exchanged on perfectly competitive markets, the social optimum can be reached and is compatible with the principle of unanimous evaluations of the allocations. The social optimum is an allocation that cannot be modified in order to improve the welfare of everybody. Then, a social configuration is Pareto-optimal if and only if there is no other alternative configuration in which at least one individual is better off and nobody else worse off. By the same way, a social configuration A is Pareto-superior to a social configuration B if and only if at least one individual is better off in A than B without any other individual being worse off in A than B.

We have to remark however that if it exists, a Pareto optimum is not unique. The Pareto criterion is a comparative and a conservative criterion. It does not say (it cannot do it) what social configuration must be preferred to other. Let us take an example with two individuals (1 and 2) and two social configurations (A and B):

Configurations |

A |

B |

||

|

|

|

|

|

Individuals |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

20 |

25 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

40 |

35 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

To total configuration is the same in all cases (equals 60). But we do not know, using Pareto criterion, what configuration to choose in order to reach a socially optimal state. So, an allocation to which no other is unanimously preferred

62

is not necessary the allocation unanimously preferred! There can be a multiplicity of Pareto optima.

Pareto’s fundamental result is the demonstration that each allocation associated with a competitive equilibrium is a social optimum in the sense above.

But it is not possible to assert, using Pareto’s criterion, that the competitive market structure is superior in general to all others possible configurations.

63

Chapter III: Introduction to the Keynesian Economics

The quantity theory of money, revisited by Wicksell, led to a consideration of the role of saving and investment in the determination of national income. Here the key price to equilibrate saving and investment is the rate of interest. What marks the break with Keynes’s The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936) is the switch from prices to real output as the central variable to be explained (that is the first opposition between the neoclassical tradition and the Keynesian analysis and the foundation of the difference between the micro and the macro analysis). The break is also bound up with the suggestion that it is variations in output or in income rather than variations in the rate of interest that permit the equalisation of saving and investment.

1. The theoretical features of the Keynesian revolution

In the 40s, the vast majority of economists in the Western World were converted to the Keynesianism. The Keynesianism seems to be a scientific revolution because it involved a theoretical crisis, the emergence of a new paradigm and of a new generation adopting this new paradigm. Moreover, years of depression radicalised many people (and many economists) who were converted naturally to the new paradigm.

The novel idea comes therefore into the picture: it is investment and not saving that sparks off changes in income. Instead of starting with the public’s willingness to save and then showing how investment adapts itself to saving via the interest rate, Keynes posited a largely autonomous flow of investment (depending on the expectations of entrepreneurs –called animal spirits-) and shows how savings will be generated via the multiplier to satisfy that level of investment. Then, all the propositions of economic policies are called to be modified.

Keynes argued the necessity of abandoning rigid free-trade orthodoxy. He stated that there are spheres of activity in which private initiative carries out an essential economic role and in which the state should not interfere, while there are also spheres of activity in which the state operates in a better way than the private sector. Therefore, the state should take on the role of concerted and deliberate

64

management of the economy, albeit by means of a limited number of political instruments (like credit control and regulations of the process of formation and allocation of savings).

We can summarize the principle theoretical features of this paradigm by following Blaug (1997, p.646):

1)A shift in method from micro to macroeconomics. The reasoning on an aggregate level of economy replaces the theoretical structure founded on individual maximization programs.

2)The model considers the short-run rather than the long period. The search for a long-run equilibrium is replaced by the aim to improve the functioning of the economy throughout state interventions.

3)In some limits, aggregate consumption and aggregate saving are considered to be stable functions of income while the investment is treated as inherently volatile, subject to uncertainty and depending on entrepreneurial expectations.

4)Saving and investment are assumed to be carried out by different agents and for different reasons. The equilibrium between saving and investment is obtained by changes of income.

5)The real wages are treated as determined by the volume of employment rather than the other way around.

In the Keynesian system, an equilibrium level of income and output need not correspond to a situation of full employment because the market does not evolve throughout a self-adjusting mechanism which will necessarily drive the economy to use the capital to full capacity and to employ the entire available labour force.

In the General Theory, Keynes suggested that the poor has higher marginal propensity to consume than the rich, then output and employment could be raised by the redistribution of income from the rich to the poor. The analysis is therefore founded on macroeconomic structure and the representative agent pattern is replaced by the hypothesis of heterogeneous individuals (poor and rich, entrepreneur and wage-earners, private decisions and public policies, and so on).

65

2. The effective demand and the investment

In the General Theory, Keynes argued that it is not production which generates expenditure and demand, but the expenditure decisions which generate demand; then production adjusts to demand. Consequently, the identification of the factors that determine the expenditure decisions becomes the first stage in order to study a given employment (or unemployment) level in the economy.

2. 1. Expenditure decisions

The theory of effective demand is suggested to understand the formation and the evolution of the expenditure decisions. The whole demand in the economy, the aggregate demand (Y) is subdivided into an autonomous component which is investment (I), and an induced component which is consumption (C):

Y= C+I.

The consumption function is given by:

Co+cY,

where Co is the minimum consumption level whatever the aggregate income Y. C is an increasing function of Y. c is the propensity to consume, that is the part of the aggregate (national) income which is used for the consumption expenditures of whole private economic agents. Therefore, at the macroeconomic equilibrium level, the aggregate income, the aggregate demand and aggregate expenditure are equal:

Y=I+C=I+C0+cY

66

I, C, S

|

C+I’ |

E |

C+I |

|

|

|

C |

S

I’

E’

I

45°  Y

Y

Ye Y’e

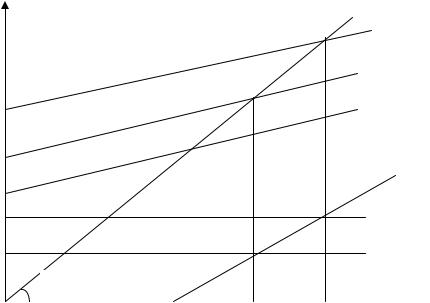

In the figure above, the horizontal axis represents produced and distributed income and the vertical axis represents expenditure. The 45° line is given by all the points where aggregate expenditure equals income. The equilibrium point is E (C + I line meets the 45° line). The expenditure generates exactly the amount of demand and production which will give the income Ye, necessary to finance the expenditure itself. As C depends on the level of income, I will determine the level of activity. At the equilibrium point (equality between aggregate demand and aggregate supply), earned incomes are spent and savings (S) are equal to investments.

2. 2. The investment multiplier

Contrary to the neoclassical view, Keynes said that I does generate the necessary saving for financing the economic activity. Investment decisions are independent of the amount of available savings. Given the propensity to consume, c, it is the amount of investment which will determine, by means of multiplier, the level of income:

Y = C + I

Y = C0 + cY + I

Y – cY = C0 + I

67

Y (1- c) = C0 + I

Y= |

C0 |

|

1 |

I . |

|

1- c |

1 c |

||||

|

|

|

As C0 is given (put it equals to ‘a’), the change of Y will depend on the change of I and the proportion of this interdependency is given by the multiplier (1/(1-c)):

Y=a+ |

|

|

1 |

I . |

|

1 |

c |

||||

|

|

||||

This assertion has a deep theoretical consequence. If the level of activity (hence, the level of employment) depends on the level of investment, the neoclassical assertion of the full employment reached by means of the changes in relative factor prices becomes irrelevant. But Keynes did not fully develop the implications of the theory of effective demand; however he thought that the investment decisions depend on the expectations of entrepreneurs, these expectations being founded on some subjective projections about future, called animal sprits. This way of thinking the capitalist production process calls for a different approach and cannot use the neoclassical equilibrium hypothesis which constitutes a set of decision rules given at the beginning of the analysis and not obtained as a consequence of private and decentralized individual economic decisions.

Parallel to this theoretical change, Keynes focussed also on the problem of why investments do not normally settle at the full employment level. Investment is assumed to be depending on the marginal efficiency of capital (r), which is an estimate of the future returns of investments (Rt, with t = 0, 1…, n) r is calculated as the discount rates that makes the present value of the future returns of investments equal to the cost of the capital goods (K):

n |

R t |

|

K |

||

|

||

t 0 (1 r)t |

||

68