Теорграмматика / Блох М.Я. Семенова Т.Н. Тимофеева С.В. - Theoretical English Grammar. Seminars. Практикум по теоретической грамматике английского языка - 2010

.pdfprogressive aspects as well as the simple past:

14*

212 Seminars on Theoretical English Grammar

(1) / wrote my letter of 16 July 1972 with a special pen. (2a) / have written with a special pen since 1972.

(2bi) / wrote with a special pen from 1969 to 1972. (2bii) / was writing poetry with a special pen.

3.36 The Future

There is no obvious future tense in English corresponding to the time/tense relation for present and past. Instead there are several possibilities for denoting future time. Futurity, modality, and aspect are closely related, and future time is rendered by means of modal auxiliaries or semi-auxiliaries, or by simple present forms or progressive forms.

3.37 Will and Shall

will or '11 + infinitive in all persons

shall + infinitive (in 1st person only; chiefly BrE) / will/shall arrive tomorrow.

He'll be here in half an hour.

The future and modal functions of these auxiliaries can hardly be separated but "shall" and, particularly, "will" are the closest approximation to a colourless, neutral future. "Will" for future can be used in all persons throughout the English-speaking world, whereas "shall" (for 1st person) is largely restricted in this usage to southern BrE.

3.45 Mood

Mood is expressed in English to a very minor extent by the subjunctive as in

So be it then! to a much greater extent by

past form as in

If you taught me, I would learn quickly. but above

all, by means of the modal auxiliaries, as in

//is strange that he should have left so early.

3.46The Subjunctive

Three categories of subjunctive may be distinguished:

(a) The MANDATIVE Subjunctive in that-clauses has only one form, the base (V); this means there is lack of the regular indicative concord between subject and finite verb in the 3rd person singular present, and the present and past tenses are indistinguishable. This subjunctive can be used with any verb in subordinate that-clause when the main clause contains an expression of recommendation, resolution, demand, and so on (We demand, require, move, insist, suggest, ask, etc., that...). The use of this subjunctive occurs chiefly in formal style (and especially in AmE) where in less formal contexts one would rather make use of other devices, such as toinfinitive or should + infinitive. It is necessary that every member inform himself of these rules. It is necessary that every member should inform himself of these

rules. It is necessary for every member to inform himself of these rules.

(b)The FORMULAIC Subjunctive also consists of the base (V) but is only used in clauses in certain set expressions which have to be learned as wholes:

Come what may, we will go ahead.

God save the Queen!

Suffice it to say that...

Be that as it may...

Heaven forbid that...

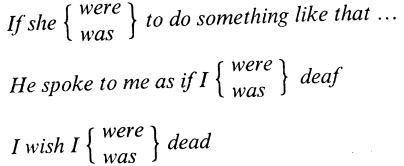

(c)The SUBJUNCTIVE "were" is hypothetical in meaning and is

used in conditional and concessive clauses and in subordinate clauses after optative verbs like "wish". It occurs as the 1st and 3rd person singular past of the verb "be", matching the indicative "was", which is the more common in less formal style:

: PRESSI ( HERSON )

214 Seminars on Theoretical English Grammar

Questions:

1.What classification of verbs did the authors work out?

2.What principles do they suggest to differentiate between finite and nonfinite verbs?

3.What criteria of classifying verb phrases do they suggest?

4.How do they define the categorial meanings of tense, aspect, and mood?

5.Why do they treat tense, aspect, and mood as interconnected categories?

6.What does the analysis of the present and past tenses in relation to the progressive and perfective aspects show?

7.How do they substantiate the absence of the future tense in English?

8.What three categories of subjunctive do they distinguish?

7.

Qraustein G., Hoffmann A., Schentke M.

English Grammar. A University Handbook

The Category of Mood

The verbal category of mood serves to express the speaker's attitude towards the factuality ("Faktizitat") of a state-of-affairs described in a sentence. By means of this category the speaker can present the state-of-affairs as real, existing in fact, or as hypothetical, i.e. not necessarily real. In contemporary English the category of mood is decaying, the forms of the hypothetical mood (subjunctive) falling more and more into disuse and in many cases being replaced by modals.

Structure and Functions

The category of mood consists of three constituents, the indicative and the subjunctives I and II. They form a binary opposition, the unmarked member (indicative) being opposed to the marked member, which appears in two variants (subjunctive I and II):

,, (~ _____ f call-0 (no '-s'/tense/correlation/aspect) call-0 + lcall-ed

The categorial meaning of the category of mood indicates the hypothetical nature of the state-of-affairs described as seen from the speaker's point of view. The functions of the marked forms are identical with the categorial meaning of the category of mood:

Long live the workers' revolution. It is time Kurt went on a diet.

The function of the unmarked form negates this categorial meaning in that it indicates the "reality of the state-of-affairs":

A small section of the working class has now more access to culture

than it had in the 1930's.

These formal and functional relations form the mood paradigm:

It is only the indicative that has full tense, correlation and aspect marking. [...] The subjunctive I form of the verb is homonymous with the SimPres (0) form: "I suggest that he come/write/go". "Be" has the subjunctive I form "be". Subjunctive I, which is more common in AmE than in BrE where it is used only in formal style, occurs in an optative or a possibility function:

The boss insisted that Willard arrive at eight sharp. She suggested that I be the cook. (AmE) [...] If any person be found guilty, he shall have the right of appeal. The subjunctive II form of the verb is homonymous with its Sim-• Past form and may be used with reference to the present and future: »• "if I called/wrote/went". "Be" has "were" in all persons, in colloquial , speech also "was". Reference to the past (or anterior

present) is made I, by adding "have -ed-participle": "if I had called/written/gone". Sub-I junctive II may combine with aspect markers: "if I were going to call/ were calling". It represents a state- of-affairs as imaginary. [...]/ wish I had thought of him before.

He took it from me as if I were handing him the Cullinam diamond.

(pp. 174-175)

: PRESSI ( HERSON )

216 |

Seminars on Theoretical English Grammar |

Questions:

1.What is the categorial meaning of mood?

2.What types of mood forms do the authors recognize?

3.What functions are performed by Subjunctive I and SubjiH|Ctjve jj cording to the authors?

References

Blokh M. Y. A Course in Theoretical English Grammar. - M., 20QQ _ p 119. 197. . .

. - , 1975. - . 97-148. . .

, 2001.- . 25-55. .,

., .

. - ., 1981. - , 46-87

. . -

. - ., 1986. .

. - .: , , 1996. - . 479,202- 250.

Francis W.N. "he Structure of American English. - N.Y., __ M

Graustein G., Hoffmann A., Schentke M. English Grammar. University Handbook. - Leipzig: VEB Verlag Enzyklopadie, 1977. - {> 174.175

Joos M. The English Verb. Form and Meaning. - Madison & Milwaukee 1964.

Ilyish B. The Structure of Modern English. - L., 1971. - P. 123.129 Quirk R., Greenbaum S., Leech G., Svartvik J. A University Qrammar of

English.-M., 1982. Strang B. Modern English Structure. - London, 1962.

Seminar 8

ADJECTIVE AND ADVERB

1.A general outline of the adjective.

2.Classification of adjectives.

3.The problem of the stative.

4.The category of adjectival comparison.

5.A general outline of the adverb.

6.Structural types of adverbs. Modern interpretations of the "to bring up" type of adverbs.

7.The lexemic subcategorizations of the adverbs ending in "-ly".

1. Adjective as a Part of Speech

The adjective expresses the categorial semantics of property of a i substance. It means that each adjective used in the text presupposes relation to some noun the property of whose referent it denotes, such fas its material, colour, dimensions, position, state, and other charac-fteristics both permanent and temporary. It follows from this that, i unlike nouns, adjectives do not possess a full nominative value.

Adjectives are distinguished by a specific combinability with nouns, which they modify, if not accompanied by adjuncts, usually in pre-position, and occasionally in post-position; by a combinability with link-verbs, both functional and notional; by a combinability with modifying adverbs.

In the sentence the adjective performs the functions of an attribute I and a predicative. Of the two, the more specific function of the adjec-

218 |

Seminars on Theoretical English Grammar |

tive is that of an attribute, since the function of a predicative can be performed by the noun as well.

To the derivational features of adjectives belong a number of suffixes and prefixes.of which the most important are: -ful (hopeful), -less (flawless), -ish (bluish), -ous (famous), -ive (decorative), -ic (basic) ;un- (unprecedented), in- (inaccurate),pre- (premature). Among the adjectival affixes should also be named the prefix a-, constitutive for the stative subclass.

The English adjective is distinguished by the hybrid category of comparison. The ability of an adjective to form degrees of comparison is usually taken as a formal sign of its qualitative character, in opposition to a relative adjective which is understood as incapable of forming degrees of comparison by definition. However, in actual speech the described principle of distinction is not at all strictly observed.

On the one hand, adjectives can denote such qualities of substances which are incompatible with the idea of degrees of comparison. Here refer adjectives like extinct, immobile, deaf, final, fixed, etc.

On the other hand, many adjectives considered under the heading of relative still can form degrees of comparison, thereby, as it were, transforming the denoted relative property of a substance into such as can be graded quantitatively, e.g.: of a military design - of a less military design -of a more military design.

In order to overcome the demonstrated lack of rigour in the differentiation of qualitative and relative adjectives, we may introduce an additional linguistic distinction which is more adaptable to the chances of usage. The suggested distinction is based on the evaluative function of adjectives. According as they actually give some qualitative evaluation to the substance referent or only point out its corresponding native property, all the adjective functions may be grammatically divided into "evaluative" and "specificative". In particular, one and the same adjective, irrespective of its being basically "relative" or "qualitative", can be used either in the evaluative function or in the specificative function.

The introduced distinction between the evaluative and specificative uses of adjectives, in the long run, emphasizes the fact that the morphological category of comparison (comparison degrees) is potentially represented in the whole class of adjectives and is constitutive for it.

Seminar 8. Adjective and Adverb |

219 |

2. Category of Adjectival Comparison

The category of adjectival comparison expresses the quantitative characteristic of the quality of a nounal referent. The category is constituted by the opposition of the three forms known under the heading of degrees of comparison; the basic form (positive degree), having no features of comparison; the comparative degree form, having the feature of restricted superiority (which limits the comparison to two elements only); the superlative degree form, having the feature of unrestricted superiority.

Both formally and semantically, the oppositional basis of the category of comparison displays a binary nature. In terms of the three degrees of comparison, at the upper level of presentation the superiority degrees as the marked member of the opposition are contrasted against the positive degree as its unmarked member. The superiority degrees, in their turn, form the opposition of the lower level of presentation, where the comparative degree features the functionally weak member, and the superlative degree, respectively, the strong member. The whole of the double oppositional unity, considered from the semantic angle, constitutes a gradual ternary opposition.

The analytical forms of comparison, as different from the synthetic forms, are used to express emphasis, thus complementing the synthetic forms in the sphere of this important stylistic connotation. Analytical degrees of comparison are devoid of the feature of "semantic idiomatism" characteristic of some other categorial analytical forms, such as, e.g., the forms of the verbal perfect. For this reason the analytical degrees of comparison invite some linguists to call in question their claim to a categorial status in English grammar.

3. Elative Most-Construction

The mosJ-combination with the indefinite article deserves special consideration. This combination is a common means of expressing elative evaluations of substance properties.

The definite article with the elative raosr-construction is also possible, if leaving the elative function less distinctly recognizable. Cf:

They gave a most spectacular show -1 found myself in the most awkward situation. The expressive nature of the elative superlative as such

: PRESSI ( HERSON )

220 |

Seminars on Theoretical English Grammar |

provides it with a permanent grammatico-stylistic status in the language. The expressive peculiarity of the form consists in the immediate combination of the two features which outwardly contradict each other: the categorial form of the superlative, on the one hand, and the absence of a comparison, on the other.

4. Less/Least-Construction

After examining the combinations of less/least with the basic form of the adjective we must say that they are similar to the more/most- combinations, and constitute specific forms of comparison, which may be called forms of "reverse comparison". The two types of forms cannot be syntagmatically combined in one and the same form of the word, which shows the unity of the category of comparison. Thus, the whole category includes not three, but five different forms, making up the two series - respectively, direct and reverse. Of these, the reverse series of comparison (the reverse superiority degrees, or "inferiority degrees", for that matter) is of far lesser importance than the direct one, which evidently can be explained by semantic reasons.

5. Adverb as a Part of Speech

The adverb is usually defined as a word expressing either property of an action, or property of another property, or circumstances in which an action occurs. This definition, though certainly informative and instructive, fails to directly point out the relation between the adverb and the adjective as the primary qualifying part of speech.

To overcome this drawback, we should define the adverb as a notional word expressing a non-substantive property, that is, a property of a non-substantive referent. This formula immediately shows the actual correlation between the adverb and the adjective, since the adjective is a word expressing a substantive property.

In accord with their categorial semantics adverbs are characterized by a combinability with verbs, adjectives and words of adverbial nature. The functions of adverbs in these combinations consist in expressing different adverbial modifiers. Adverbs can also refer to whole situations; in this function they are considered under the heading of "situation-determinants".

Seminar 8. Adjective and Adverb |

221 |

In accord with their word-building structure adverbs may be simple and derived.

The typical adverbial affixes in affixal derivation are, first and foremost, the basic and only productive adverbial suffix -ly (slowly), and then a couple of others of limited distribution, such as -ways (sideways), -wise (clockwise), -ward(s) (homewards). The characteristic adverbial prefix is a- (away). Among the adverbs there are also peculiar composite formations and phrasal formations of prepositional, conjunctional and other types: sometimes, at least, to and fro, etc.

Adverbs are commonly divided into qualitative, quantitative and circumstantial. Qualitative adverbs express immediate, inherently non-graded qualities of actions and other qualities. The typical adverbs of this kind are qualitative adverbs in -ly. E.g.: bitterly, plainly. The adverbs interpreted as "quantitative" include words of degree. These are specific lexical units of semi-functional nature expressing quality measure, or gradational evaluation of qualities, e.g.: of high degree: very, quite; of excessive degree: too, awfully; of unexpected degree: surprisingly; of moderate degree: relatively; of low degree: a little; of approximate degree: almost; of optimal degree: adequately; of inadequate degree: unbearably; of under-degree: hardly. Circumstantial adverbs are divided into functional and notional.

The functional circumstantial adverbs are words of pronominal nature. Besides quantitative (numerical) adverbs they include adverbs of time, place, manner, cause, consequence. Many of these words are used as syntactic connectives and question-forming functionals. Here belong such words as now, here, when, where, so, thus, how, why, etc. As for circumstantial notional adverbs, they include adverbs of time

(today, never, shortly) and adverbs of place (homeward(s), near, ashore). The two varieties express a general idea of temporal and spacial orientation and essentially perform deictic (indicative) functions in the broader sense. On this ground they may be united under the general heading of "orientative" adverbs.

Thus, the whole class of adverbs will be divided, first, into nominal and pronominal, and the nominal adverbs will be subdivided into qualitative and orientative, the former including genuine qualitative adverbs and degree adverbs, the latter falling into temporal and local adverbs, with further possible subdivisions of more detailed specifications.

222 Seminars on Theoretical English Grammar

As is the case with adjectives, this lexemic subcategorization of adverbs should be accompanied by a more functional and flexible division into evaluative and specificative, connected with the categorial expression of comparison. Each adverb subject to evaluational grading by degree words expresses the category of comparison, much in the same way as adjectives do. Thus, not only qualitative, but also orientative adverbs, proving they come under the heading of evaluative, are included into the categorial system of comparison, e.g.: ashore

- more ashore - most ashore - less ashore - least ashore.

Questions:

*1. What categorial meaning does the adjective express?

•2. What does the adjectival specific combinability find its expression in?

3.What proves the lack of rigid demarcation line between the traditionally identified qualitative and relative subclasses of adjectives?

4.What is the principle of differentiation between evaluative and specifica

tive adjectives?

* 5. What does the category of adjectival comparison express?

• 6. What arguments enable linguists to treat the category of adjectival comparison as a five-member category?

7.What does the expressive peculiarity of the elative superlative consist in?

8.What is the categorial meaning of the adverb?

19. What combinability are adverbs characterized by?

10.What is typical of the adverbial word-building structure?

11.What semantically relevant sets of adverbs can be singled out?

12.How is the whole class of adverbs structured?

'13. What does the similarity between the adjectival degrees of comparison and adverbial degrees of comparison find its expression in?

I.State the classification features of the adjectives and adverbs used in the given sentences.

MODEL: "I found myself weary and yet wakeful, tossing restlessly from side to side..."

"weary" - a qualitative evaluative adjective; "wakeful" - a qualitative speculative adjective; "restlessly" - an evaluative qualitative adverb.

1.Rosemary Fell was not exactly beautiful. Pretty? Well, if you took her to pieces... But why be so cruel as to take anyone to pieces? She was

223

young, brilliant, extremely modern, exquisitely dressed, amazingly wellread in the newest of the new books, and her parties were the most delicious mixture of the really important people and... artists - quaint creatures, discoveries of hers, some of them too terrifying for words, but others quite presentable and amusing (Mansfield).

2.He was in a great quiet room with ebony walls and a dull illumination that was too faint, too subtle, to be called a light (Fitzgerald).

3."There!" cried Rosemary again, as they reached her beautiful big bed room with the curtains drawn, the fire leaping on the wonderful lacquer furniture, her gold cushions and the primroses and blue rags (Mansfield).

4.Medley had already risen hurriedly to his feet. The look in his eyes said he was going straight to his telephone to tell Doctor Llewellyn apologet ically that he, Llewellyn, was a superb doctor and he, Medley, could hear him perfectly. Oxborrow was on his heels. In two minutes the room was clear of all but Con, Andrew, and the remainder of the beer (Cronin).

5.She was helpful, pervasive, honest, hungry, and loyal (Cheever).

6.Dr. Trench. I will be plain with you. I know that Blanche has a quick temper. It is part of her strong character and her physical courage, which is greater than that of most men, I can assure you. You must be pre pared for that. If this quarrel is only Blanche's temper, you may take my word for it that it will be over before to-morrow (Shaw).

7.The elder man was about forty with a proud vacuous face, intelligent eyes, and a robust figure (Fitzgerald).

8.He was tall and homely^ wore horn-rimmed glasses, and spoke in a deep voice (Cheever).

II.Comment on the use of the forms of superlative degree of the adjective and on the use of the words "more" and "most" in the following sentences.

MODEL: "It was a most unpleasant telephone call." This is a case of the elative "mos/-construction". The morphological form "a most unpleasant" is not a superlative degree of the adjective but an elative form expressing a high degree of the quality in question.

a)

1.She who had been most upset and terrified at the morning's discovery now seemed to regard the whole thing as a personal insult (James).

2.The Fifth Symphony by Beethoven is a most beautiful piece of music.

3.I have been with good people, far better than you (Ch. Bronte).

4.Sure, it's difficult to do about in the wrongest way possible (Wilson).

5.The more we go into the thing, the more complex the matter becomes (Wilson).

: PRESSI ( HERSON )

224 |

Seminars on Theoretical English Grammar |

b)

1.When Sister Cecilia entered, he rose and gave her his most distinguished bow (Cronin).

2.And he thought how much more advanced and broad-minded the young er generation was (Bennett).

3.She was the least experienced of all (Bennett).

4.She is best when she is not trying to show off (Bennett).

5.He was none the wiser for that answer, but he did not try to analyse it (Aldridge).

c)

1.You're the most complete man I've ever known (Hemingway).

2.Now in Hades - as you know if you ever had been there the names of the more fashionable preparatory schools and colleges mean very little (Fitzgerald).

3.As they came closer, John saw that it was the tail-light of an immense automobile, larger and more magnificent than any he had ever seen (Fitzgerald).

4.It was a most unhappy day for me when I discovered how ignorant I am (Saroyan).

5."Have you got a dollar?" asked Tripp, with his most fawning look and his dog-like eyes that blinked in the narrow space between his highgrowing matted beard and his low-growing matted hair (O.Henry).

d)

1.She had, however, great hopes of Mrs. Copleigh, and felt that once thoroughly rested herself, she would be able to lead the conversation to the most fruitful subjects possible (Christie).

2."Still on your quest? A sad task and so unlikely to meet with success. I really think it was a most unreasonable request to make." (Christie)

3."I know. I know. I'm often the same. I say things and I don't really know what I mean by them. Most vexing." (Christie)

4."Then it is he whom you suspect?" "I dare not go so far as that. But of the three he is perhaps the least unlikely." (Doyle)

5.In the first place, your Grace, I am bound to tell you that you have placed yourself in a most serious position in the eyes of the law (Doyle).

III.Give the forms of degrees of comparison and state whether they are formed in a synthetic, analytical or suppletive way,

a)wet, merry, real, far;

b)kind-hearted, shy, little, friendly;

Seminar 8. Adjective and Adverb |

225 |

|

c)certain, comical, severe, well-off;

d)sophisticated, clumsy, old-fashioned, good-looking.

IV. Translate the given phrases into English using Adjective + Noun, Noun + Noun combinations where possible, or else prepositions or genitive case (give double variants where possible):

a), ( ),

, ,

, , , ,

, , , , ,

, ,

, , , ,

, , ;

b), , ,

, , , ,

, , ,

; , , , ,

, ;

c), , , ,

, ,

, , , ,

, ;

d), , , ,

, , , ,

;

e), , ,

, , , ,

, , , ,

, , , ,

, , ,

, .

V.Give the Russian equivalents for the English word combinations:

a.iron rations, iron foundry (ironworks), iron industry, ironware (iron mongery), ferrous metal, ferrous oxide;

b.celestial map, sky-force, celestial food, sky-line, skyway, celestial navi-

rgation;

c. sea-boy, sea-water, naval base, "sea dog", Admiralty, Admiralty mile,

sea-cock, dog-fish, echinus;

d.sea-hedgehog, starfish, sea-horse, sea-dye, grass-wrack, sea kale, "old salt", sea-cliff, sea-cow, sea-lane.

15 - 3548

226 |

Seminars on Theoretical English Grammar |

VI. Account for the peculiarity of the underlined word-forms:

1.I am the more bad because I realize where my badness lies.

2.Wimbledon will be yet more hot tomorrow.

3.The economies are such more vulnerable, such more weak.

4.Certainly, Ann was doing nothing to prevent Pride's finally coming out of the everything into the here.

5.He turned out to be even more odd than I had expected.

6.That's the way among that class. They up and give the old woman a friendly clap, just as you or me would swear at the missus.

7."You see, by this time we was on the peacefulest of terms." (O.Henry)

8."Well, you never could be fly," says Myra with her special laugh, which was the provokingest sound I ever heard except the rattle of an empty canteen against my saddle-horn (O.Henry).

Selected Reader

1.

Quirk R., Qreenbaum S., Leech Q., Svartvik J.

A University Grammar of English

Adjectives

5.1. Characteristics of the Adjective

We cannot tell whether a word is an adjective by looking at it in isolation: the form does not necessarily indicate its syntactic function. Some suffixes are indeed found only with adjectives, e.g.: -ous, but many common adjectives have no identifying shape, e.g.: good, hot, little, young, fat. Nor can we identify a word as an adjective merely considering what inflections or affixes it will allow. [...]

5.2.

Most adjectives can be both attributive and predicative, but some are either attributive only or predicative only.

Seminar 8. Adjective and Adverb |

227 |

Two other features usually apply to adjectives:

(1)Most can be premodified by the intensifier "very", e.g.: The children are very happy.

(2)Most can take comparative and superlative forms. The com> parison may be by means of inflections, e.g.: "The children are happier now", "They are the happiest people I know" or by the addition of the premodifiers "more" and "most" (periphrastic comparison), e.g.: "These students are more intelligent", "They are the most beautiful paintings I have ever seen." [...]

5.4.

Adjectives can sometimes be postpositive, i.e. they can sometimes follow the item they modify. A postposed adjective (together with any complementation it may have) can usually be regarded as a re, duced relative clause.

Indefinite pronouns ending in -body, -one, -thing, -where can be modified only postpositively: I want to try on something larger (7.e,

"which is large'').

Postposition is obligatory for a few adjectives, which have a dif, ferent sense when they occur attributively or predicatively. The most common are probably "elect" ("soon to take office") and "proper" ("as strictly defined"), as in: "the president elecf\ "the City of . don proper". In several compounds (mostly legal or quasi-legal) the adjective is postposed, the most common being: attorney general, body politic, court martial, heir apparent, notary public (AmE), postmaster general.

Postposition (in preference to attributive position) is usual for a few a-adjectives and for "absent", "present", "concerned", "involved", which normally do not occur attributively in the relevant sense:

The house ablaze is next door to mine. The people involved were not found.

Some postposed adjectives, especially those ending in "-able" or "-ible", retain the basic meaning they have in attributive position but convey the implication that what they are denoting has only a temporary application. Thus, the star visible refers to stars that are visible at a time specified or implied, while the visible stars refers to a category of stars that can (at appropriate times) be seen.

15*

: PRESSI ( HERSON )