книги / Местное самоуправление в современном обществе

..pdfразным направлениям. Во-вторых, по словам представителей ОМСУ края, из «свободного соревнования» участие в конкурсе превращается в обязательство. На органы власти поселений давление оказывают районные власти, последние, в свою очередь, находятся под «прессом» региона. Одним из направлений будущих исследований могут стать, к примеру, анализ и выявление корреляции между локальными политическими процессами (результатами голосования на федеральных, региональных и местных выборах, конфигурацией местных элит, наличием межэлитных конфликтов – во взаимодействиях региона и МО, органов МСУ, бизнес-элит, общественности и т.д.) и итогами конкурсов. Согласно анализу бюджетной статистики за 2009–2015 годы, как правило, победителями конкурсов становятся одни и те же МО. С чем связано появление «случайных победителей» – муниципалитетов, единожды занявших призовое место?

В заключение отметим, безусловно, региональные конкурсы МО служат дополнительным доходным источником как лично для представителей муниципальной власти, так и в целом для местного бюджета. Они позволяют повысить активность ОМСУ в реализации вопросов местного значения и улучшении качества муниципального управления.

Список литературы

1.Всероссийский конкурс на звание «Самое благоустроенное городское (сельское) поселение России» по итогам 2012 го-

да» [Электронный ресурс]. – URL: http://www.окмо.рф/?id=2123 (дата обращения: 03.12.2016).

2.Шугрина Е.С. Тенденции развития местного самоуправления: ключевые события 2015–2016 гг. и их влияние на состояние местного самоуправления // Доклад о состоянии местного самоуправления в Российской Федерации: Современные вызовы

иперспективы развития / под ред. Е. С. Шугриной. – М.: Про-

спект, 2016. – С. 8.

311

3. Зуйкина А.С. «Стратегии подчинения» региональных властей в отношении муниципалитетов в Пермском крае (на примере распределения межбюджетных трансфертов) // Вестник Перм. ун-та. Сер. Политология. – 2014. – № 1. – С. 64.

A.S. Zuykina

PUBLIC COMPETITIONS FOR THE BEST MUNICIPALITY: ADDITIONAL INCOME OR INSTRUMENT OF CONTROL?

(ON THE EXAMPLE OF PERM KRAI)

The article examines the mechanisms of the organization of public tenders to identify the most effective practices of municipal governance. The example of the Perm region the author reveals the conditions and procedure of intermunicipal competition by regional authorities. There a variety of these competitions as additional financial incentives to increase the activity of local self-governments in the implementation of local issues. Based on the analysis of fiscal statistics is dynamic as the total amount of grants allocated region to awarding of municipalities and the amount of rewards in the context of the winners. Analysis of the evaluation criteria of municipalities and materials of interviews with representatives of local selfgovernment reveal different meaning regional competitions as the instrument of state influence to the municipal political agenda.

Keywords: public competition, the best municipal practices, indicators of efficiency of administrative activity, agreement on interaction of the regional and municipal authorities, municipal political agenda

312

МЕСТНОЕ САМОУПРАВЛЕНИЕ: ЗАРУБЕЖНЫЙ ОПЫТ

S. Kuhlmann, H. Wollmann

LOCAL LEVEL TERRITORIAL REFORMS

IN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES1

Territorial organization of municipal units is one the most important aspects local self-government system which is a reason why every country is in search of the most effective model of territorial structure of municipalities. In the article, local level reforms in European countries are examined in comparative perspective. Two different patterns have been distinguished. Northern European reform pattern is based on territorial amalgamation, enlargement in scale, and pursuing administrative efficiency while in Southern European countries, reforms aim to improve inter-municipal cooperation. Germany demonstrates intermediate approach to municipal reforms. Hence, a substantial divergence between municipal reforms in Northern and Southern European countries has exposed. At the same time, convergence becomes apparent within both the group of countries.

Key words: local self-government; municipal units; territorial organization; reforms

1. Concepts and Definitions

Below the national or federal levels, the European countries, as a rule, have two-tier local government systems . The upper level is termed counties (Kreise, landsting kommuner, province etc.) and the lower level municipalities (boroughs/districts, Gemeinden, kommuner, comuni). The following illustration refers primarily to the lower (“classical”) local government level, but also can includes the “upper” level.

1 This text is a (slightly revised) excerpt from Sabine Kuhlmann & Hellmut Wollmann 2014, Introduction to Comparative Public Administration. Administrative System and Reforms in Europe, Edward Elgar, pp. 150-173

313

In most European countries, the municipal level was historically characterized by a small-sized and fragmented structure, which, often extends back to the late Middle Ages, and originated in the territorial landscape of parish communities. On the one hand, a group of countries can be identified in which national governments acted to reinforce the administrative efficiency of local government by way of territorial and demographic extension (enlargement in scale). While the democratic potential of the local government level was meant to be retained, if not enhanced, the improvement of the administrativeeconomic performance (efficiency) was given priority as a crucial frame of reference (cf. John 2010). This strategic thrust, also termed up-scaling (cf. Baldersheim/Rose 2010) was a basic guideline of the territorial reforms that, following the Second World War, were carried out in England/UK, Sweden and also in the German Länder. In the international comparative literature, one therefore speaks of a Northern European reform model (Norton 1994).

Contrasting with this Northern European country group, stands a group of countries in which the small-sized fragmented territorial structure of local government whose origin often dates back to the 18th century has largely remained unchanged. Reform attempts which the governments in these countries, too, embarked upon during the 1970s largely failed, as these reform measures were made dependent on the consent of the municipalities concerned and, as such, local approval was not obtained. Since France and Italy are prominent examples of this country group, the comparative literature refers to these as the “Southern European” reform model. In these countries, strategies (termed trans-scaling by Baldersheim/Rose) have been pursued that aim at ensuring the operative viability even of the very small-scale municipalities, by establishing inter-municipal bodies (in French: intercommunalité). The creation of such institutionalized forms of in- ter-municipal cooperation and institutional symbioses can be seen as a response to and a “substitute” for the lack of formal territorial reforms through municipal amalgamation.

314

From the outset, in the transformation of the Central and Eastern European countries from centralized communist regimes to democratic constitutional governments, great importance was also attached to the territorial and organizational restructuring of the subnational level for the development of democratic and efficient decentralized structures. Given the aspired accession to the EU, the concepts and process of the territorial restructuring of the government levels in these countries have been strongly influenced by the territorial NUTS scheme as promoted by the EU. The territorial reform profile of the transformation countries approximates partly the Northern European and partly the Southern European reform type (cf. the country studies in Horváth 2000, Swianiewicz 2010). One group of countries follows a Southern European reform pattern in that it was decided to do without municipal amalgamations despite the existing fragmentation of the municipal level and whose further fragmentation was even permitted (e.g. Hungary, Czech Republic). By contrast, in another group of countries the governments, immediately following the system change, implemented far-reaching local territorial reforms conforming to the Northern European reform profile (e.g. Bulgaria, Lithuania). This presumably reflected the intention, to territorially “modernize” the municipal level with an eye on the desired accession to the EU.

2. Northern European Reform Patterns:

Territorial Amalgamation, Enlargement in Scale,

Administrative Efficiency

2.1. United Kingdom:

“sizeism” and reform-political breathlessness

The United Kingdom epitomizes the Northern European territorial reform group. The instrumental grip of the central government level on the local level has been determined by two factors. Firstly, it was derived traditionally from the principle of parliamentary sover-

315

eignty in that parliament had the right to decide on any institutional changes on local government level by means of legislationincluding territorial. Secondly, in dealing with local governments, central government has long since been guided by an “almost obsessive predominance ... to production efficiency” (Sharpe 1993).

This logic of action instructed the early territorial reform thrust of 1888 and 1894 under which England’s subnational levels were radically revamped in order to adapt them to the policy needs of the central gov-

316

ernment (cf. Wollmann 2008). First, in 1888, elected county councils were established in the 62 historical (largely rural) counties/shires while single-tier county borough councils were provided for in 62 larger cities. Subsequently, in 1894, some 1.200 district councils were created within the counties as a completely new lower level of local government. The duality of (two-tier) county councils (with district councils within the counties) and (single-tier) county borough councils became the territorial basis for the Victorian local government model (which was greatly admired abroad) and constituted its territorial and organizational basic structure well until the 1970s.

Since then, the local government system has experienced several groundswells of radical territorial and organization changes, in which the decision-making power of parliament and the instrumental grip of the central level on the local level again became manifest. In the far-reaching reform move of 1974, for one, the district/borough councils were territorially merged through a drastic reduction of their number from 1.250 to 333, while at the same time raising their population size to an average of 170.000 inhabitants – a size far beyond any comparison and parallel in Europe-- (cf. Norton 1994; Wilson/Game 2006 et seq.) and criticized as sizeism (Stewart 2000). Secondly, the county councils whose borders reached back to the medieval shires were rescaled by cutting their number from 58 to 47 and by lifting the population average to 720.000 inhabitants. Finally, the almost century-old single-tier system of the county borough councils was abolished, while the two-tier system was expanded to now encompass the entire local government system. Consequently, even large cities such as Birmingham were reduced to the status of a district council. This downgrading was fiercely opposed and bitterly resented by Birmingham and other affected big cities.

Subsequently the British local government system experienced a series of further upheavals. In 1986, the Conservative government under Margaret Thatcher rescinded a central element of the 1974 reform. The (two-tier) structure of 36 metropolitan county councils that had been put into place in 1974 was undone. Consequently, the downgrad-

317

ing of large cities, such as Birmingham, to metropolitan district councils (within two-tier counties) was reversed. This was greatly welcomed by the large cities which thus regained their previous single-tier status. At the same time, unmistakably for party-political motives, the Thatcher government dissolved the Greater London Council, which was governed by the Labour Party and figured as an active opponent to the Thatcher government. Thus, London’s two-tier local government system that was introduced in 1965 was done away with and the single-tier status of the 32 London boroughs restored.

In the early 1990s, the Conservative government under John Major triggered still another drastic territorial and organizational turnover. In England’s urbanized areas, the two-tier system of districts/boroughs and counties that had been installed under the 1974 reform was gradually erased. Instead, by territorially, organizationally and functionally integrating counties and districts/boroughs, step-by-step 56 so-called (single-tier) unitary authorities were created, each averaging about 209.000 inhabitants (cf. Wilson/Game 2006).

As a result, at that time large scale local government structures were in place in almost all urbanized areas, whether the 36 metropolitan districts councils or the 56 unitary authorities having an average of 308.000 and 209.000 inhabitants respectively. Today, the two-tier scheme exists only in distinctly rural areas. But, even there, the population average is remarkably high, (over 100.000 in the nonmetropolitan districts, and even almost as many as 760.000 in the non-metropolitan counties.

Under the New Labour government of Tony Blair, the abolition of the Greater London Council that had been imposed by the Tory government in 1986 was reversed, as had been promised in the election campaign. Based on the referendum held in 1999, the Greater London Authority was set up as a (two-tier) London-wide local government structure while retaining the 32 London boroughs. At the Greater London level, the London Assembly was introduced as the “parliamentary” body and, at the same time, the directly elected Mayor of London was designated as the executive.

318

The many institutional shifts and ruptures which the local government structures in England have endured have been criticized as: “breathless has been the pace of change over the past 30 years” (Leach/Pierce-Smith 2001). The resulting “diversity, fragmentation and perhaps sheer messiness of British local government” (Leach/Pierce-Smith 2001) has been ascribed to an “endless piecemeal tinkering with the system and the absence of wholesale reform” (John 2001).

2.2. Sweden, Denmark: territorial anchoring of the local welfare state

In Sweden, historically a predominantly rural country, industrialization and urbanization set in as late as the 1930s, that is, much later than, for example, in the United Kingdom or Germany. Against this background the territorial reform of municipal level that was launched by the government in two phases (1952 and 1974) aimed at enabling the municipalities to act as a key local agent of Sweden’s welfare state (den lokala staten). In Sweden, too, the national parliament has the power to carry out territorial reform of the local government level without the approval or, indeed, even contrary to the wishes of the local population. Consequently, the number of municipalities was drastically reduced from 2.282 (with an average of some 2.800 inhabitants) to 290 (with an average of 31.300 inhabitants; cf. Häggroth et al. 1993).

The territorial organization of Sweden’s 20 counties (landsting kommuner) each with an average of 420.000 inhabitants have remained unaffected by this territorial reform drive. However, the three largest cities in the country (Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö) have been allotted a status (comparable to the German county-free cities and the English unitary authorities) that combines municipal and county tasks. Since the late 1990s, a reform debate hinging on a regionalization has gained momentum where also the (timehonoured) existing county boundaries have been questioned (for an overview, cf. Lidström 2010)

319

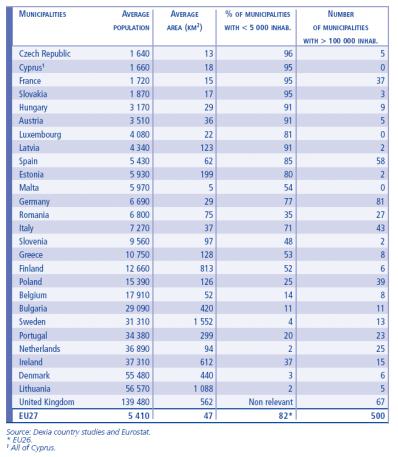

Denmark, too, provides a prime example of the Northern European territorial reform type (cf. Mouritzen 2010). In a first reform step in 1970, the total number of 1,386 municipalities (kommuner) was reduced to 271, while the number of 26 counties (amter) was cut to 14. In 2007, another even more radical reform followed suit resulting in 98 municipalities with an average of 55.400 inhabitants (cf. Vrangbaek 2010, Dexia 2008). Thus, Denmark’s municipalities have leapt to an average population size that, while staying clearly behind the unparalleled population size of British local government (“sizeism”; Stewart 2000), otherwise ranks at the top of the European local government systems. Furthermore, the 14 counties were amalgamated and transformed into five new “regions”, whose organization is oriented on the NUTS regions of the EU system (cf. Dexia 2008).

2.3. Up-scaling in Southern European and transformation countries: Greece, Bulgaria, Lithuania

Until the 1990s, Greece fell in line with the Southern European territorial pattern with its historic fragmented territorial structure of 5.825 municipalities (averaging 1,900 inhabitants). At the mesolevel, 50 prefectures were in place which, founded in 1833 as mesolevel of state administration in conformity with the French département model, carried out the bulk of public tasks, as well as being in line with the Napoleonic state model.

Greece: massive territorial reforms

During the wave of massive territorial-organizational reforms triggered in the 1990s, the state prefectures, in 1994, were transformed into 50 meso-level (prefectural) self-government bodies with elected representation (cf. Hlepas 2003). Moreover, the so-called Capodistrias reforms have conspicuously abandoned the Southern Europeantrajectory of the small-size, fragmented local territorial structure and have spectacularly all but embarked on a “North European” reform pattern. Consequently, the number of municipalities has been drastically reduced by large-scale amalgamations from 5.825 to 1.034 (now averaging 10,750 inhabitants). They are now made up

320