- •Summary Contents

- •Detailed Contents

- •Figures

- •Tables

- •Preface

- •The Disciplinary Players

- •Broad Perspectives

- •Some Key Guiding Principles

- •Why Did Agriculture Develop in the First Place?

- •The Significance of Agriculture vis-a-vis Hunting and Gathering

- •Group 1: The "niche" hunter-gatherers of Africa and Asia

- •Group 3: Hunter-gatherers who descend from former agriculturalists

- •To the Archaeological Record

- •The Hunter-Gatherer Background in the Levant, 19,000 to 9500 ac (Figure 3.3)

- •The Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (ca. 9500 to 8500 Bc)

- •The Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (ca. 8500 to 7000 Bc)

- •The Spread of the Neolithic Economy through Europe

- •Southern and Mediterranean Europe

- •Cyprus, Turkey, and Greece

- •The Balkans

- •The Mediterranean

- •Temperate and Northern Europe

- •The Danubians and the northern Mesolithic

- •The TRB and the Baltic

- •The British Isles

- •Hunters and farmers in prehistoric Europe

- •Agricultural Dispersals from Southwest Asia to the East

- •Central Asia

- •The Indian Subcontinent

- •The domesticated crops of the Indian subcontinent

- •The consequences of Mehrgarh

- •Western India: Balathal to jorwe

- •Southern India

- •The Ganges Basin and northeastern India

- •Europe and South Asia in a Nutshell

- •The Origins of the Native African Domesticates

- •The Archaeology of Early Agriculture in China

- •Later Developments (post-5000 ec) in the Chinese Neolithic

- •South of the Yangzi - Hemudu and Majiabang

- •The spread of agriculture south of Zhejiang

- •The Background to Agricultural Dispersal in Southeast Asia

- •Early Farmers in Mainland Southeast Asia

- •Early farmers in the Pacific

- •Some Necessary Background

- •Current Opinion on Agricultural Origins in the Americas

- •The Domesticated Crops

- •Maize

- •The other crops

- •Early Pottery in the Americas (Figure 8.3)

- •Early Farmers in the Americas

- •The Andes (Figure 8.4)

- •Amazonia

- •Middle America (with Mesoamerica)

- •The Southwest

- •Thank the Lord for the freeway (and the pipeline)

- •Immigrant Mesoamerican farmers in the Southwest?

- •Issues of Phylogeny and Reticulation

- •Introducing the Players

- •How Do Languages Change Through Time?

- •Macrofamilies, and more on the time factor

- •Languages in Competition - Language Shift

- •Languages in competition - contact-induced change

- •Indo-European

- •Indo-European from the Pontic steppes?

- •Where did PIE really originate and what can we know about it?

- •Colin Renfrew's contribution to the Indo-European debate

- •Afroasiatic

- •Elamite and Dravidian, and the Inds-Aryans

- •A multidisciplinary scenario for South Asian prehistory

- •Nilo-Saharan

- •Niger-Congo, with Bantu

- •East and Southeast Asia, and the Pacific

- •The Chinese and Mainland Southeast Asian language families

- •Austronesian

- •Piecing it together for East Asia

- •"Altaic, " and some difficult issues

- •The Trans New Guinea Phylum

- •The Americas - South and Central

- •South America

- •Middle America, Mesoamerica, and the Southwest

- •Uto-Aztecan

- •Eastern North America

- •Algonquian and Muskogean

- •Iroquoian, Siouan, and Caddoan

- •Did the First Farmers Spread Their Languages?

- •Do genes record history?

- •Southwest Asia and Europe

- •South Asia

- •Africa

- •East Asia

- •The Americas

- •Did Early Farmers Spread through Processes of Demic Diffusion?

- •Homeland, Spread, and Friction Zones, plus Overshoot

- •Notes

- •References

- •Index

The Significance of Agriculture vis-a-vis Hunting and Gathering

There is a point of view, quite commonly held by anthropologists and archaeologists, that hunting-gathering and agriculture are merely extremes of a continuum, along which ancient societies were able to move with relative ease (Schrire 1984; Layton et al. 1991; Armit and Finlayson 1992). Such a point of view obviously minimizes the significance of agricultural origins and in extreme form would render the concept valueless. It is true that hunter-gatherers often engage in resource management activities. But chameleon-like societies that switch from hunter-gatherer dependence to agricultural or pastoral dependence and then back again are remarkably hard to document, whether in the archaeological or ethnographic records. One really wonders if they have ever existed, outside those well-known cases in which former agriculturalists made short-term adaptations to the presence of naive faunas in previously uninhabited islands, especially in Oceania (the example of New Zealand was discussed above).

Certainly, many recent hunter-gatherers have been observed to modify their environments to some degree to encourage food yields, whether by burning, replanting, water diversion, or keeping of decoy animals or domesticated dogs; that is, by resource management techniques which might mimic protoagriculture in the archaeological record. Most agriculturalists also hunt if the opportunity is presented and always have done so throughout the archaeological record. Indeed, in the Americas, hunted meat was a major source of supply for all agriculturalists because of the absence of any major domesticated meat animals. This is probably one essential reason why the American record of agricultural and language family expansion was quite low key compared to that in the Old World.

All of this means that there is good evidence in recent societies for some degree of overlap between food collection and food production. But the whole issue here revolves around just what level of "food production" is implied. Any competent food gatherer can also be a resource manager, maybe plant an

occasional garden or even keep a few tame animals. Yet any idea that mobile hunters and gatherers can just shift in and out of an agricultural (or pastoral) dependent lifestyle at will seems unrealistic in terms of the major scheduling shifts required by the annual calendars of resource availability, movement, and activity associated with the two basic modes of production. There are very few hints of such circumstances ever occurring in the ethnographic record, and certainly none that are unchallengeable in historical veracity. Mobile foragers must give an increasing commitment to sedentism if agriculture is to become a successful mainstay of their economy - fields of growing crops can of course be abandoned for several months while people go hunting, but under such circumstances yields will be expectably low. If the foragers were sedentary prior to adopting agriculture then the transition may be less traumatic, but the difficulties that archaeologists face in tracing sedentism in pre-agricultural contexts have already been alluded to.

There is another way to approach this question of the "hardness" of the transition between hunting-gathering and agriculture. If casual shifts between agriculture and foraging had been occurring with high frequency in recent centuries, we might expect to find lots of societies still passing between the two states when they were first captured in the ethnographic record. We might also expect to see a gradual progression in the relative importance of produced versus gathered food from one extreme of dependence to the other. Is this the case?

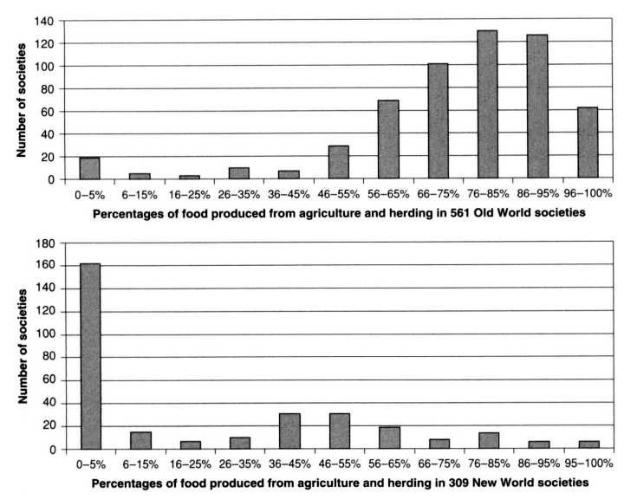

The answer to this question is not particularly obvious since so many traditional economies were transformed by contact with the Western world before the ethnographic record began to be compiled. But we have hints in the entries in the Ethnographic Atlas (Murdock 1967; Hunn and Williams 1982) for the proportional contributions of five subsistence modes (gathering, hunting, fishing, animal husbandry, and cultivation) in the diets of a total of 870 societies distributed throughout the world. In Figure 2.4 the percentages for agriculture and animal husbandry (i.e., "produced" food) are summed as one combined percentage of the total food supply for all the societies listed in the Atlas. We see some very interesting patterns.

In the Old World (Figure 2.4 top), virtually all societies which practice agriculture and/or stockbreeding derive more than 50 percent of their food supply from these two sources. Very few combine them with any major reliance

on hunting and gathering. Most exceptions to this generalization, where agricultural dependence drops in a few cases to below 50 percent, occur in Pacific Island communities where the high importance of fishing and absence of major herd animals clearly push the figures for food production downwards. In general for the Old World, we see that hunters and gatherers may practice a small amount of agriculture, and agriculturalists may practice a small amount of hunting and gathering, but the two modes of production most decisively do not merge or reveal a gentle cline. Almost no societies occupy "transitional" situations, deriving for instance 30 percent of their food from agriculture and 70 percent from hunting and gathering. In terms of Old World cultural history, such a combination has clearly not been stable since ethnographic records began to be compiled.'

Figure 2.4 Top: The percentages of produced food in the diets of a sample of 561 Old World societies. Bottom: The percentages of produced food in the diets of a

sample of 309 New World societies. Data from Murdock 1967.

This suggests, in terms of the Old World cultural trajectory, that huntinggathering and agricultural modes of production cannot be indiscriminately mixed. Being good at one alone is a better option for most societies than balancing both. Mobile hunters cannot stay near crops to protect them from predators, farmers cannot always abandon their crops to hunt, and often do not need to do so if there are hunters and gatherers living nearby. Trade-and- exchange forms of mutualism between the two modes of production tend to keep them apart in many ethnographic situations, and hunters often benefit from the presence of wild animals attracted by agricultural activities. This Old World observation, of a sharp ethnographic separation between dependence on hunting-gathering and farming, is contrary to the views of those who believe that hunting-gathering and agriculture are simply alternative strategies which societies can choose at will.

The graph for the 309 American societies listed in the Atlas (Figure 2.4 bottom) is by no means as striking as that for the Old World in terms of the degree of dependence on food production. Of course, the Americas (especially North America) had, at European contact, an immensely greater number of hunter-gatherer societies than the Old World (excluding Australia). But it is clear that the graph is still a muchmuted version of its bimodal Old World counterpart, with a lesser degree of dependence on food production in the majority of American societies. As in the Old World, there is an obvious nadir at 16-25 percent, but in the New World we also find very few societies more than 60 percent dependent on agriculture and herding. This reflects some fundamental differences between the Old and New Worlds in terms of environments and history.

The New World, from the perspective of early agriculturalists, had a much greater extent of landscapes marginal or prohibitive to agriculture than the Old. It also had virtually no major stockbreeding economies and its agricultural trajectory has occupied much less time than in much of the Old World. Without stockbreeding, food production was necessarily reduced in proportional importance because most societies needed to obtain meat from wild sources, whether by fishing or hunting, and both these modes tended to be more important in combination than gathering amongst those American societies

listed as having agriculture. In the New World, agriculture was in general not the basis of such powerful subsistence economies as in the Old World. Even so, and despite these differences, the fact remains that both Old and New World populations evidently found it problematic to shift in and out of agricultural dependence on a regular basis.

Under What Circumstances Might Hunters and

Gatherers Have

Adopted Agriculture in Prehistory?

The agricultural dispersals described in this book involved populations who appear, according to archaeological evidence and linguistic reconstructions, to have depended quite highly on agriculture for their subsistence. If ancient hunter-gatherers did adopt agriculture through cultural diffusion, then we must consider under what circumstances they would have shifted into fully agricultural economies. This is not a trivial question, at least not for those who wish to understand the spread of agriculture in more depth than that offered by the botanical and archaeological databases alone.

We can attack this issue comparatively, to some extent, from the ethnographic and historical records pertaining to hunter-gatherer behavior in agricultural latitudes in the recent past. But the issue becomes complex when the precise nature of those hunter-gatherer groups who survived to enter the ethnographic record is taken into consideration. Ethnographic hunters survive because they have never adopted agriculture, but most are also oppressed by current political and social conditions that discourage them from doing so. They can, for the most part, only offer negative information, about why people did not adopt or invent agriculture. We simply have no detailed historical records of huntergatherers actually adopting agriculture in a successful and long-term manner, even though many practice minimal cultivation on a casual basis.

There are historical provisos, however. On the one hand, the ethnographic record is essentially a creation of Western colonial societies and belongs to a period of history when conditions for successful agricultural adoption have been extremely discouraging. One could perhaps reject it as irrelevant to issues of agricultural adoption in the Neolithic. On the other hand, we have records from northern Australia and California of people who were technically in a position to adopt agriculture from neighboring cultivators for several centuries prior to major European domination of their lives, but who never did so. We

also have circumstantial evidence for many groups of former hunter-gatherers who probably did adopt agriculture or pastoralism in relatively recent times, although these adoptions predate direct ethnographic records and so are rather uncertain in historical trajectory. From these behavioral perspectives ethnography is surely relevant as a comparative database, even if the comparisons cannot be extended to the interpretation of trajectories of longterm human history.

In order to approach the ethnographic record systematically and to extract useful comparative information, it is essential not to treat all recorded ethnographic huntergatherer societies as being one simple category, or as having had the same basic historical trajectories stretching back far into the Pleistocene past (Kent 1996). None of these societies are fossils. Huntergatherers have had histories just as tumultuous in many cases as have agriculturalists (Lee and Daly 1999). This chapter favors a separation of the world's surviving hunter-gatherers into three groups based on historical understanding, albeit often rather faint, of their origins and relationships with cultivators in the past. Not all hunter-gatherer groups can be placed unequivocally in one of the three groups, but there are sufficient that can to allow a number of fairly convincing observations.

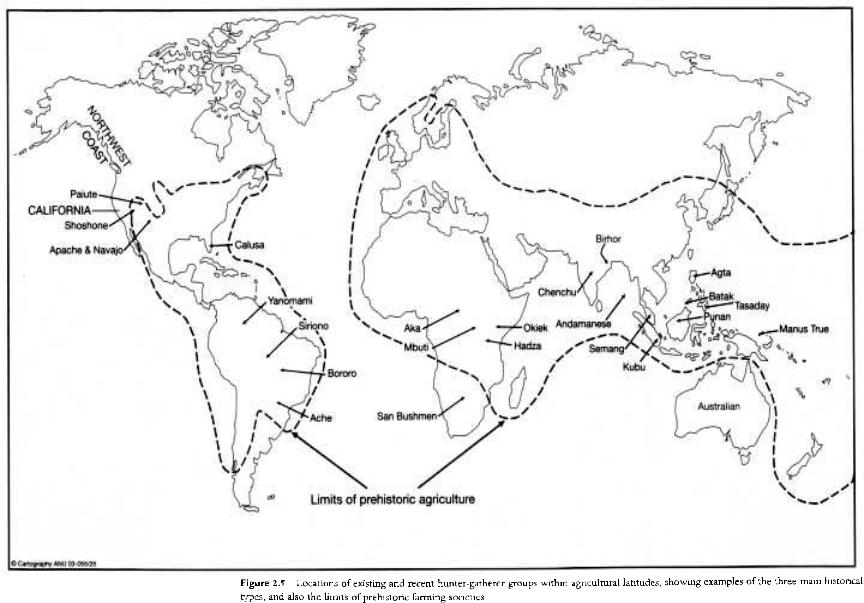

Of the three groups, the first two can be distinguished as "original" huntergatherers in the sense that they are presumed, at least by most authorities, to have unbroken ancestries within the hunter-gatherer economy extending back into the Pleistocene. Group 1 hunter-gatherers are enclosed within farming and pastoralist landscapes, whereas those of group 2 are (or were) free of such constraints. Group 3 hunter-gatherers have a range of apparently derived hunter-gatherer economies, created by specialization out of former lifestyles that in many cases included agriculture.

Hunter-gatherers who live completely (or mostly) beyond the range of agriculture in the cold latitudes are excluded for obvious reasons from the following discussion. Such groups include the Ainu (who did have a marginal foray into agriculture in recent centuries), plus of course the many cold temperate, Arctic, and southern South American hunter-gatherer populations. The members of the three groups to be discussed below all live in, or just beyond, those tropical and temperate latitudes within which agriculture was or is generally possible (Figure 2.5).