- •Summary Contents

- •Detailed Contents

- •Figures

- •Tables

- •Preface

- •The Disciplinary Players

- •Broad Perspectives

- •Some Key Guiding Principles

- •Why Did Agriculture Develop in the First Place?

- •The Significance of Agriculture vis-a-vis Hunting and Gathering

- •Group 1: The "niche" hunter-gatherers of Africa and Asia

- •Group 3: Hunter-gatherers who descend from former agriculturalists

- •To the Archaeological Record

- •The Hunter-Gatherer Background in the Levant, 19,000 to 9500 ac (Figure 3.3)

- •The Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (ca. 9500 to 8500 Bc)

- •The Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (ca. 8500 to 7000 Bc)

- •The Spread of the Neolithic Economy through Europe

- •Southern and Mediterranean Europe

- •Cyprus, Turkey, and Greece

- •The Balkans

- •The Mediterranean

- •Temperate and Northern Europe

- •The Danubians and the northern Mesolithic

- •The TRB and the Baltic

- •The British Isles

- •Hunters and farmers in prehistoric Europe

- •Agricultural Dispersals from Southwest Asia to the East

- •Central Asia

- •The Indian Subcontinent

- •The domesticated crops of the Indian subcontinent

- •The consequences of Mehrgarh

- •Western India: Balathal to jorwe

- •Southern India

- •The Ganges Basin and northeastern India

- •Europe and South Asia in a Nutshell

- •The Origins of the Native African Domesticates

- •The Archaeology of Early Agriculture in China

- •Later Developments (post-5000 ec) in the Chinese Neolithic

- •South of the Yangzi - Hemudu and Majiabang

- •The spread of agriculture south of Zhejiang

- •The Background to Agricultural Dispersal in Southeast Asia

- •Early Farmers in Mainland Southeast Asia

- •Early farmers in the Pacific

- •Some Necessary Background

- •Current Opinion on Agricultural Origins in the Americas

- •The Domesticated Crops

- •Maize

- •The other crops

- •Early Pottery in the Americas (Figure 8.3)

- •Early Farmers in the Americas

- •The Andes (Figure 8.4)

- •Amazonia

- •Middle America (with Mesoamerica)

- •The Southwest

- •Thank the Lord for the freeway (and the pipeline)

- •Immigrant Mesoamerican farmers in the Southwest?

- •Issues of Phylogeny and Reticulation

- •Introducing the Players

- •How Do Languages Change Through Time?

- •Macrofamilies, and more on the time factor

- •Languages in Competition - Language Shift

- •Languages in competition - contact-induced change

- •Indo-European

- •Indo-European from the Pontic steppes?

- •Where did PIE really originate and what can we know about it?

- •Colin Renfrew's contribution to the Indo-European debate

- •Afroasiatic

- •Elamite and Dravidian, and the Inds-Aryans

- •A multidisciplinary scenario for South Asian prehistory

- •Nilo-Saharan

- •Niger-Congo, with Bantu

- •East and Southeast Asia, and the Pacific

- •The Chinese and Mainland Southeast Asian language families

- •Austronesian

- •Piecing it together for East Asia

- •"Altaic, " and some difficult issues

- •The Trans New Guinea Phylum

- •The Americas - South and Central

- •South America

- •Middle America, Mesoamerica, and the Southwest

- •Uto-Aztecan

- •Eastern North America

- •Algonquian and Muskogean

- •Iroquoian, Siouan, and Caddoan

- •Did the First Farmers Spread Their Languages?

- •Do genes record history?

- •Southwest Asia and Europe

- •South Asia

- •Africa

- •East Asia

- •The Americas

- •Did Early Farmers Spread through Processes of Demic Diffusion?

- •Homeland, Spread, and Friction Zones, plus Overshoot

- •Notes

- •References

- •Index

The Southwest

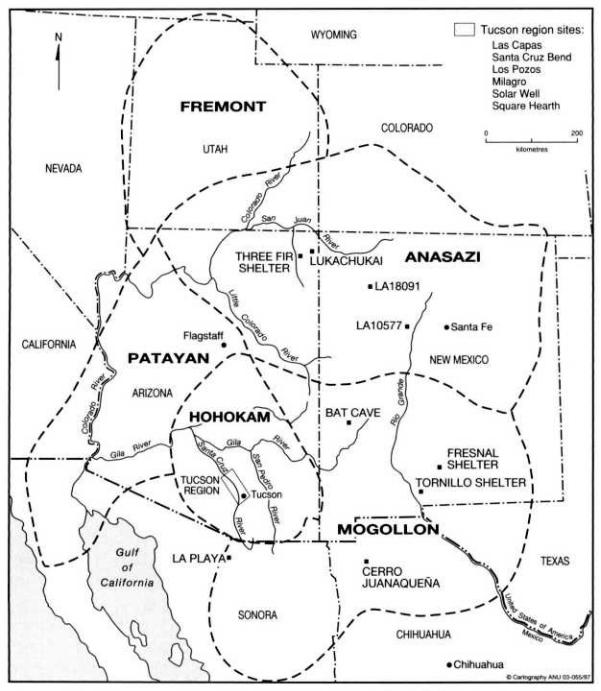

The southwestern USA, comprising the states of Nevada, Utah, Arizona, western Colorado, and western New Mexico, was not a locus of independent agricultural development. But it was one of the most important areas in North America for the development of agricultural societies, the record of these being most clearly enshrined in the great Anasazi, Mogollon, and Hohokam pueblo ruins of the early second millennium AD (Figure 8.7). Living descendants of these ancient agriculturalists include the extant pueblo-dwelling Hopi, Zuni, and Rio Grande peoples of parts of northern Arizona and New Mexico.

The Southwest, however, has served not only as an environmental backdrop for the development of pueblo societies with stone or adobe architecture. For instance, the ethnographic Tarahumara of Sonora and Chihuahua in northwestern Mexico did not build pueblos, and were fairly mobile in settlement terms (Hard and Merrill 1992; Graham 1994). The Great Basin of Nevada and Utah and the northern regions of the Colorado Plateau housed mobile hunter-gatherer populations. So did much of the former Anasazi region of the southern Colorado Plateau, as a result of the southward migration of the Athabaskan-speaking Navajo and Apache. This hunter-gatherer migration occurred after AD 1400 (Matson 2003), doubtless assisted by the abandonment of most of the former pueblo settlements by that time.

Figure 8.7 Map of the US Southwest showing early sites with maize older than 1000 BC (filled squares), and the approximate boundaries of the subsequent Hohokam, Mogollon, Anasazi, Patayan, and Fremont cultural regions. Data from Coe et al. 1989; Mabry 1998; Archaeology Southwest 13, No. 1, pp. 8-9, 1999.

The southwestern USA, in terms of its agricultural prehistory since about

2000 BC, can be seen as a northerly continuation of Mesoamerica. Indeed, Paul Kirchhoff (1954) used the concept of the "Greater Southwest" to include Mexico north of the Tropic of Cancer. It is a region of semi-desert, steppe, and high altitude forest, interspersed with bands of fertile riverine alluvium. Irrigation was essential in most regions apart from those at very high altitude, and agriculture was limited to the summer months by winter frosts and snow in many upland regions. The major crops in late prehistory were of Mesoamerican origin - especially maize, squash, beans, and cotton - and reached their greatest geographical extent a little before AD 1300, extending to as far north as the Fremont culture of Utah. Also of Mesoamerican origin was the practice of soaking maize in lime water before cooking, and the making of maize flour tortillas.

Since AD 1300, Amerindian agriculture in the Southwest has contracted drastically, some say due to drought and climate change, others to that frequent combination of too many people, overly intensive agriculture, and too fragile an environment. My sympathies are toward the latter explanation, perhaps a combination of both, but this is not a topic to delay us here since we are more concerned with the beginning of agriculture than the end (except insofar as the Fremont culture and the Great Basin are concerned, to both of which we will return in chapter 10 in connection with the origins of the Numic-speaking peoples).

The Southwest has an immensely detailed archaeological record, albeit one still with major gaps in the early agricultural period prior to 400 BC. These gaps are currently being filled, but the lack of evidence until recently for an agricultural lifestyle from the early period between 2000 and 400 BC, beyond sporadic finds of maize, is surely one reason why southwestern archaeologists, with rare exceptions, have in the past held almost universally to the idea that resident late Archaic foragers everywhere adopted maize cultivation to increase economic security and obviate risk (Ford 1985; Wills 1988; Jennings 1989; Minnis 1992; Upham 1994; papers in Roth ed. 1996; Plog 1997; Cordell 1997). This offers essentially a no-moves explanation favoring cultural continuity within the Southwest, from the Archaic to the period of Pueblo decline. Late Archaic hunter-gatherer populations are claimed to have remained essentially mobile with only subsidiary cultivation throughout the final millennium ac, until they began to settle down in settlements of "Basketmaker II" pit houses

with irrigation farming after about 400 BC.

However, the idea that the agricultural transition in the Southwest was no more than a long episode of hunter-gatherer adoption in situ has always had some detractors, some more strongly opinionated than others. For instance, according to Spencer and Jennings (1977:253): "we can only agree that the first Hohokam were no doubt a group of transplanted Mexican Indians establishing a northern outpost with a technology appropriate for subduing the desert wastes of the Gila and Salt Valleys, where Phoenix, Arizona, now stands." It is perhaps only fair to state that Jesse Jennings (1989) later changed his mind, returning to the prevailing scenario of non-movement. But another founder-figure in Southwestern archaeology, Emil Haury (1986), favored an introduction of maize and pottery into southern Arizona by population movement from Mexico at about 300 BC. Haury, however, like most other southwestern archaeologists, always believed that agriculture was spread by hunter-gatherer adoption into the higher altitude Mogollon and Anasazi regions, and it must be stated here that current research still supports such an explanation (Matson 2003).

One researcher to realize the significance of the period of farming introduction prior to Basketmaker II was Michael Berry (1985:304):

the introduction of maize farming was accomplished through sociocultural intrusion rather than through diffusion of agriculture to hunter-gatherer populations ... there is no reason to expect that a successfully adapted hunting and gathering culture would voluntarily adopt a practice that imposes so many constraints on mobility and whose seasonal maintenance and harvest requirements conflict with the seasonality of so many productive wild resources ... The gradualist model ... errs in failing to acknowledge the all-or-nothing nature of maize agriculture. It is impossible to sustain a plant that is not self-propagating for any length of time without a total commitment to its planting, maintenance and harvesting on a year to year basis ... everything seems to point to colonization by small groups of farmers whose cultural ties are ultimately (though probably not directly) traceable to Mesoamerica.

In perhaps the most wide-ranging review of early southwestern agriculture

published to date, R. G. Matson (1991) was obliged to take an "on the fence" position on the immigration versus indigenous-adoption issue, perhaps rightly so at that time. He was able to note, however, without taking sides, that maize dependency, pit house settlements, and a new type of side-notched projectile point called the San Pedro Point had appeared in southern Arizona and on the Colorado Plateau by 1000 BC. New discoveries in southern Arizona relate directly to this phase and have completely revolutionized earlier views.