- •Summary Contents

- •Detailed Contents

- •Figures

- •Tables

- •Preface

- •The Disciplinary Players

- •Broad Perspectives

- •Some Key Guiding Principles

- •Why Did Agriculture Develop in the First Place?

- •The Significance of Agriculture vis-a-vis Hunting and Gathering

- •Group 1: The "niche" hunter-gatherers of Africa and Asia

- •Group 3: Hunter-gatherers who descend from former agriculturalists

- •To the Archaeological Record

- •The Hunter-Gatherer Background in the Levant, 19,000 to 9500 ac (Figure 3.3)

- •The Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (ca. 9500 to 8500 Bc)

- •The Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (ca. 8500 to 7000 Bc)

- •The Spread of the Neolithic Economy through Europe

- •Southern and Mediterranean Europe

- •Cyprus, Turkey, and Greece

- •The Balkans

- •The Mediterranean

- •Temperate and Northern Europe

- •The Danubians and the northern Mesolithic

- •The TRB and the Baltic

- •The British Isles

- •Hunters and farmers in prehistoric Europe

- •Agricultural Dispersals from Southwest Asia to the East

- •Central Asia

- •The Indian Subcontinent

- •The domesticated crops of the Indian subcontinent

- •The consequences of Mehrgarh

- •Western India: Balathal to jorwe

- •Southern India

- •The Ganges Basin and northeastern India

- •Europe and South Asia in a Nutshell

- •The Origins of the Native African Domesticates

- •The Archaeology of Early Agriculture in China

- •Later Developments (post-5000 ec) in the Chinese Neolithic

- •South of the Yangzi - Hemudu and Majiabang

- •The spread of agriculture south of Zhejiang

- •The Background to Agricultural Dispersal in Southeast Asia

- •Early Farmers in Mainland Southeast Asia

- •Early farmers in the Pacific

- •Some Necessary Background

- •Current Opinion on Agricultural Origins in the Americas

- •The Domesticated Crops

- •Maize

- •The other crops

- •Early Pottery in the Americas (Figure 8.3)

- •Early Farmers in the Americas

- •The Andes (Figure 8.4)

- •Amazonia

- •Middle America (with Mesoamerica)

- •The Southwest

- •Thank the Lord for the freeway (and the pipeline)

- •Immigrant Mesoamerican farmers in the Southwest?

- •Issues of Phylogeny and Reticulation

- •Introducing the Players

- •How Do Languages Change Through Time?

- •Macrofamilies, and more on the time factor

- •Languages in Competition - Language Shift

- •Languages in competition - contact-induced change

- •Indo-European

- •Indo-European from the Pontic steppes?

- •Where did PIE really originate and what can we know about it?

- •Colin Renfrew's contribution to the Indo-European debate

- •Afroasiatic

- •Elamite and Dravidian, and the Inds-Aryans

- •A multidisciplinary scenario for South Asian prehistory

- •Nilo-Saharan

- •Niger-Congo, with Bantu

- •East and Southeast Asia, and the Pacific

- •The Chinese and Mainland Southeast Asian language families

- •Austronesian

- •Piecing it together for East Asia

- •"Altaic, " and some difficult issues

- •The Trans New Guinea Phylum

- •The Americas - South and Central

- •South America

- •Middle America, Mesoamerica, and the Southwest

- •Uto-Aztecan

- •Eastern North America

- •Algonquian and Muskogean

- •Iroquoian, Siouan, and Caddoan

- •Did the First Farmers Spread Their Languages?

- •Do genes record history?

- •Southwest Asia and Europe

- •South Asia

- •Africa

- •East Asia

- •The Americas

- •Did Early Farmers Spread through Processes of Demic Diffusion?

- •Homeland, Spread, and Friction Zones, plus Overshoot

- •Notes

- •References

- •Index

Afroasiatic

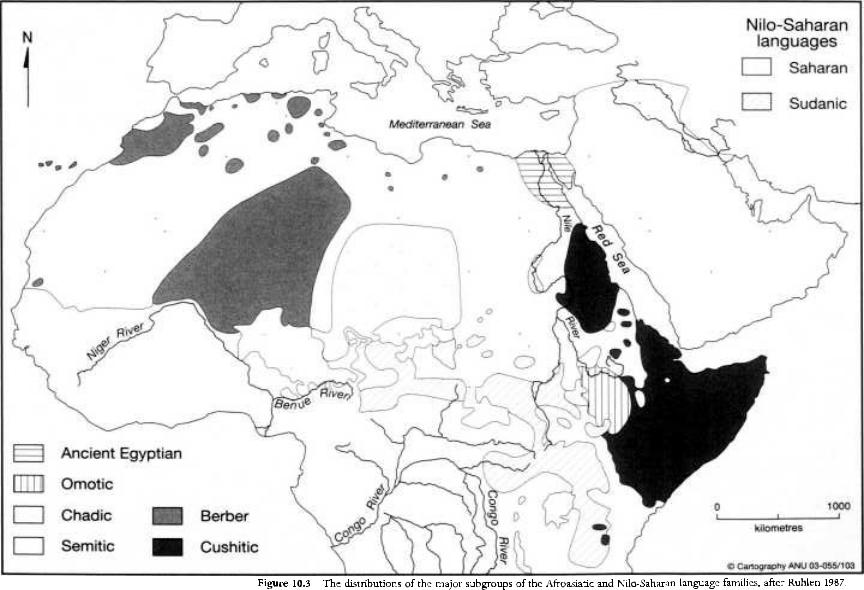

The Afroasiatic (AA) language family (Figure 10.3) contains six subgroups, of which Ancient Egyptian (or Coptic in historical times), Semitic, and Berber are agreed by most linguists to form a single node (Boreafrasian of Christopher Ehret 1995, with several phonological innovations). Chadic and Cushitic form separate subgroups, as does a poorly known and small language subgroup in southwestern Ethiopia, termed Omotic.3 The present-day widespread distribution of Semitic languages in North Africa does not reflect in situ descent directly from the earliest history of this family, since Arabic spread very widely after the seventh-century Arab conquests, and the ancestors of the more diverse Ethiopic languages (including Amharic), also in the Semitic subgroup, spread from Arabia during the second millennium BC (Ehret 2000).

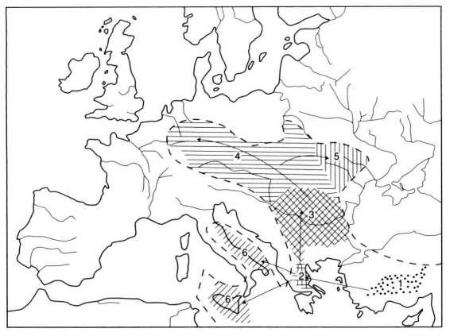

Figure 10.2 Colin Renfrew's reconstruction of the Indo-European homeland in central Anatolia and the first expansions of Indo-European languages into Europe. From Renfrew 1999.

There are two quite separate bodies of opinion concerning AA prehistory. One school, for which linguists Christopher Ehret (1979, 1995, 2003), Lionel Bender (1982), and Roger Blench (1993, 1999) are perhaps the main proponents, favors a homeland in northeastern Africa on the grounds that five of the six AA subgroups (excluding Semitic) occur only in Africa, including those perceived to be the most ancient in phylogenetic terms. The precise location of the homeland varies a little according to author, oscillating through Ethiopia and Sudan toward the Red Sea coast, where live the Beja, apparently representing a very early linguistic split within the Cushitic subgroup. These linguists tend to regard early AA expansion as pre-agricultural, although not pre-herding in Ehret's view, thus perhaps to be equated with population spread into the eastern Sahara consequent upon the postglacial wetter climatic conditions after about 10,000 years ago. Ehret (2003), for instance, states that Cushitic, Chadic, Berber, and Semitic all have independently derived agricultural protovocabularies, but that Proto-Cushitic already had some cattle vocabulary at the time of its break-up, and thus may have had an incipient herding economy.

The other major school, composed mainly of Russian linguists, strongly favors a Southwest Asian and specifically Levant homeland. This opinion is based entirely on vocabulary reconstruction rather than the "center-of-gravity " assumptions of the Northeast Africa school. Apart from one rather isolated claim for an AA expansion out of the Levant during the Aurignacian over 30,000 years ago (McCall 1998), the core case for the Levant school is based on the following observations:

1.Glottochronological considerations, calibrated against data on ancient Egyptian and Semitic languages (Greenberg 1990:12), suggest that PAA is perhaps a little older than PIE (between 10,000 and 7000 BC).

2.The reconstructed vocabulary of PAA does not contain any specifically agricultural cognates, but it does include names for a number of plants and animals that are of Asian, not North African origin (sheep, goat, barley, chickpea, for instance: Blazek 1999; Militarev 2000, 2003). Militarev favors early agricultural correlations.

3.Proto-Semitic is of undoubted Levant origin and has a full agropastoral

vocabulary (Dolgopolsky 1993; Diakonoff 1998).

These observations do not form conclusive proof of a Levant origin for the whole AA family, and we seem to be sitting on a slightly unyielding fence. My suspicions, with Colin Renfrew (1991), are that PAA does indeed have a Levant rather than a Northeast African origin, but I have to admit that this view is based more on an understanding of the record of early Holocene population movement than of any absolute markers of linguistic phylogeny. The spread of Neolithic cultures from the Levant into Egypt at about 5500 BC, or perhaps before, combined with the possibility of a PPNB movement of caprovine herders down the western side of the Arabian Peninsula in the wetter conditions of the early Holocene, are suggestive of a bifurcatory movement of early farmers and pastoralists, with sheep, goats, wheat, and barley, into Africa by two routes:

1.Southern Levant into Egypt, leading eventually to further movement of early Berber languages and goat herding into the northern Sahara.

2.A separate movement, mainly pastoralist with sheep and goat herding rather than agriculture, through western Arabia and across to East Africa, leading to Cushitic, Chadic, and presumably Omotic.

Taking linguistic and archaeological evidence into consideration, it is also possible that the movement through Arabia occurred first, perhaps a millennium or more before that into Egypt. Linguistically, this would explain why Cushitic, Omotic, and Chadic are believed by many linguists to be deeper in a phylogenetic sense than the other families (unless there has been a great deal of contact-induced change, as in the case of the western Melanesian languages within Austronesian). It would also explain why the Egyptian Neolithic as known at present started after the PPNB, during the Pottery Neolithic.

This view of a Levant origin takes into account details of the archaeological record, of proto-vocabulary reconstruction, and of existing evidence for population movement during the early Holocene. The opposing view of an African origin is based on linguistic subgrouping data and has no archaeology

in support, unless one guess-links AA dispersal to the warmer and wetter climate of the Sahara in the early Holocene. But this, of course, cannot explain Semitic, which reveals no direct traces at all of an African origin, and it also runs up against the view, widely held, that the early NiloSaharan languages would be better candidates for a linkage with the early Holocene Saharan cattle herders. A Levant origin for AA fits the general picture better, as it is currently understood, than does an African origin. The testing of this hypothesis lies in the future - for instance in the archaeology of Ethiopia and the linguistics of the little-known Omotic subgroup.