- •Summary Contents

- •Detailed Contents

- •Figures

- •Tables

- •Preface

- •The Disciplinary Players

- •Broad Perspectives

- •Some Key Guiding Principles

- •Why Did Agriculture Develop in the First Place?

- •The Significance of Agriculture vis-a-vis Hunting and Gathering

- •Group 1: The "niche" hunter-gatherers of Africa and Asia

- •Group 3: Hunter-gatherers who descend from former agriculturalists

- •To the Archaeological Record

- •The Hunter-Gatherer Background in the Levant, 19,000 to 9500 ac (Figure 3.3)

- •The Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (ca. 9500 to 8500 Bc)

- •The Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (ca. 8500 to 7000 Bc)

- •The Spread of the Neolithic Economy through Europe

- •Southern and Mediterranean Europe

- •Cyprus, Turkey, and Greece

- •The Balkans

- •The Mediterranean

- •Temperate and Northern Europe

- •The Danubians and the northern Mesolithic

- •The TRB and the Baltic

- •The British Isles

- •Hunters and farmers in prehistoric Europe

- •Agricultural Dispersals from Southwest Asia to the East

- •Central Asia

- •The Indian Subcontinent

- •The domesticated crops of the Indian subcontinent

- •The consequences of Mehrgarh

- •Western India: Balathal to jorwe

- •Southern India

- •The Ganges Basin and northeastern India

- •Europe and South Asia in a Nutshell

- •The Origins of the Native African Domesticates

- •The Archaeology of Early Agriculture in China

- •Later Developments (post-5000 ec) in the Chinese Neolithic

- •South of the Yangzi - Hemudu and Majiabang

- •The spread of agriculture south of Zhejiang

- •The Background to Agricultural Dispersal in Southeast Asia

- •Early Farmers in Mainland Southeast Asia

- •Early farmers in the Pacific

- •Some Necessary Background

- •Current Opinion on Agricultural Origins in the Americas

- •The Domesticated Crops

- •Maize

- •The other crops

- •Early Pottery in the Americas (Figure 8.3)

- •Early Farmers in the Americas

- •The Andes (Figure 8.4)

- •Amazonia

- •Middle America (with Mesoamerica)

- •The Southwest

- •Thank the Lord for the freeway (and the pipeline)

- •Immigrant Mesoamerican farmers in the Southwest?

- •Issues of Phylogeny and Reticulation

- •Introducing the Players

- •How Do Languages Change Through Time?

- •Macrofamilies, and more on the time factor

- •Languages in Competition - Language Shift

- •Languages in competition - contact-induced change

- •Indo-European

- •Indo-European from the Pontic steppes?

- •Where did PIE really originate and what can we know about it?

- •Colin Renfrew's contribution to the Indo-European debate

- •Afroasiatic

- •Elamite and Dravidian, and the Inds-Aryans

- •A multidisciplinary scenario for South Asian prehistory

- •Nilo-Saharan

- •Niger-Congo, with Bantu

- •East and Southeast Asia, and the Pacific

- •The Chinese and Mainland Southeast Asian language families

- •Austronesian

- •Piecing it together for East Asia

- •"Altaic, " and some difficult issues

- •The Trans New Guinea Phylum

- •The Americas - South and Central

- •South America

- •Middle America, Mesoamerica, and the Southwest

- •Uto-Aztecan

- •Eastern North America

- •Algonquian and Muskogean

- •Iroquoian, Siouan, and Caddoan

- •Did the First Farmers Spread Their Languages?

- •Do genes record history?

- •Southwest Asia and Europe

- •South Asia

- •Africa

- •East Asia

- •The Americas

- •Did Early Farmers Spread through Processes of Demic Diffusion?

- •Homeland, Spread, and Friction Zones, plus Overshoot

- •Notes

- •References

- •Index

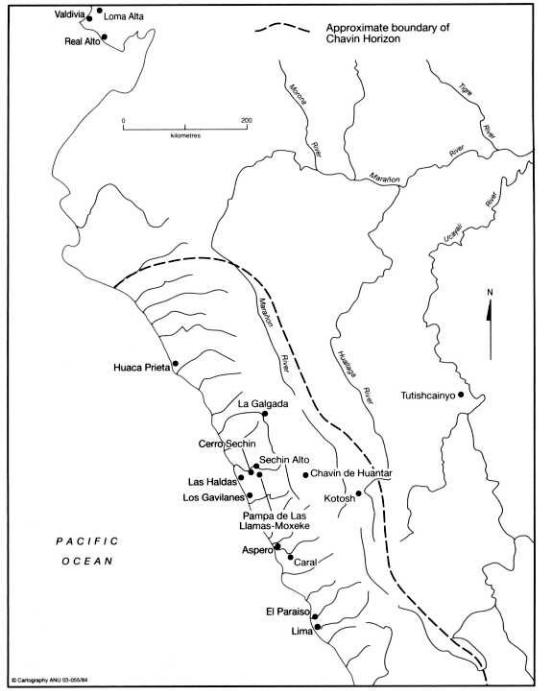

The Andes (Figure 8.4)

The Formative sequence in South America is often stated to begin with the Valdivia cultural complex of the semi-arid southern coastline of Ecuador at about 4000 BC, although the early stages of the sequence are a little unclear and there seems to be only very insecure evidence for sedentary settlements, pottery, and agriculture prior to about 3000 BC (Staller 2001). Four sites have yielded the most important evidence - Valdivia itself, and the riverine sites of Real Alto, Loma Alta, and La Emerenciana. The settlement debris in Real Alto and Loma Alta was arranged in U-shaped mounded plans, open across one end, covering more than one hectare in extent in the case of Real Alto, with sufficient pole and thatch elliptical houses for estimated populations of 150 to 200 people (Damp 1984:582). Although maize phytoliths are claimed to occur in Early Valdivia layers (as discussed above - see Pearsall 2002), actual macrofossils do not include maize until the second millennium ac. Instead, the Early Valdivia domesticated plant repertoire included squash, canavalia beans, the tuber achira, and cotton for textiles and fishing gear. Interestingly, the Valdivia people were capable of making sea crossings, as shown by the existence of a Valdivia shrine on Isla de la Plata, 23 kilometers offshore in the Pacific Ocean (Brunhes 1994:82).

Northern Peru now takes center stage, owing to a remarkable degree of labor investment in some massive residential and ceremonial complexes during the Late Preceramic Period (3000 to 2000 Be), the Initial Period (2000 to 900 Be), and the Early Horizon (900 to 200 Bc). These sites occur along the Pacific desert coast with its permanent rivers, in the lower valleys of some of these rivers, and in the northern and central highlands. Mark Cohen (1977b:164) has suggested, on the basis of site surveys in the Ancon-Chillon valleys of central coastal Peru, that populations might have increased between 15 and 30 times during the Late Preceramic Period, fueled by a combination of agriculture and the rich maritime resources of the cold Humboldt Current. Such phenomenal population growth is attested in the remains of some remarkable Late Preceramic sites in the short coastal river valleys of northern and central Peru - sites such as Huaca Prieta, Aspero, Caral, Las Haldas, Huaynuna, Los

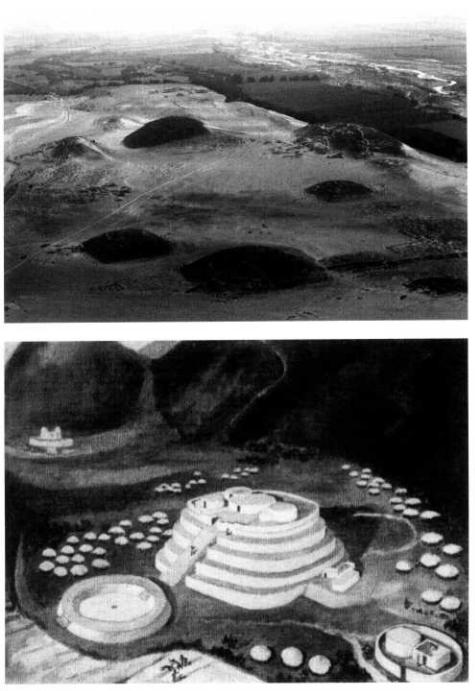

Gavilanes, and El Paraiso, the latter with occupation debris extending over 58 hectares. Recent research at Caral in the Supe Valley has revealed six large platform mounds up to 18 meters high around a rectangular open space (Figure 8.5A), together with two sunken circular plazas, and residential complexes, the whole extending over 65 hectares (Shady Solis et al. 2001).

Figure 8.4 Andean Late Preceramic, Initial Period, and Early Horizon archaeological sites and complexes discussed in the text.

One of the most interesting sites of this phase is La Galgada in the Tablachaca Valley of inland northern Peru (Grieder et al. 1988). Today, La Galgada is in a rather forbidding semi-arid area, 1,100 meters above sea level, that looks very marginal for agriculture. But during the Late Preceramic a ten-kilometer stretch of the valley bottom supported at least 11 agricultural sites. La Galgada, like El Paraiso on the coast, apparently produced cotton in large quantities utilizing a riverine field system fed by irrigation canals. The base of the deposits was not reached during the excavations in the 1980s, but the lowest layers reached date to about 2700 Bc and have an architectural style focused on small rooms with "ventilated hearths," four being set atop an oval stone-faced stepped pyramid 15 meters high (Figure 8.5B). Similar rooms have also been excavated at Kotosh, about 300 kilometers southeast of La Galgada, one termed the "Temple of the Crossed Hands" because of the survival of two such adobe reliefs beneath wall niches (Izumi and Terada 1972).

Artifacts found within the dry deposits at La Galgada include twined cotton textiles, netting, barkcloth, turquoise, marine shells, and Amazonian bird feathers, some of these items attesting to wide trade contacts. We witness during this period a remarkable agreement of architectural and artistic style through the northern and central Peruvian highlands, and also in sites on the coast. The significance of this wide horizon-like distribution in the Late Preceramic at about 2000 Bc, particularly of ritual paraphernalia, is commented upon by Thomas Pozorski (1996:350):

Closer similarities early in the sequence suggest that this was the time of greatest communication or influence, apparently in the area of religion or ritual. Subsequent divergence of form ... reveals that interaction, at least in this sphere, may have waned.

During the Late Preceramic Period in northern and central Peru, apart from significant quantities of maritime resources in coastal regions, subsistence depended on irrigation cultivation of squash (including Mexican Cucurbita moschata), beans, sweet potato, potato, achira, chili peppers, and avocados (of

Mexican origin). Cotton was widely grown, but there are no signs of maize. Michael Moseley (1975) also lists manioc and the highland tubers oca and ullucu for Preceramic coastal sites in the Ancon region, near Lima. This suggests that the highlands and lowlands of the northern Andes were in contact at this time, an unsurprising conclusion which is reinforced by some very precise parallels in textile designs and ceremonial architecture, for instance in the above-mentioned rooms with central hearths ventilated by under-floor passages found in the highland sites of La Galgada and Kotosh, and in the lowland Casma Valley sites of Huaynuna and Pampa de las Llamas-Moxeke (Pozorski and Pozorski 1992; Pozorski 1996).

Figure 8.5 A) The ceremonial area of Caral during the Late Preceramic, about 2500 Bc. Large platform mounds and associated residential complexes surround a quandrangular plaza about 600 meters long. From Shady Solis et al. 2001. B) Reconstruction of the ceremonial area at La Galgada during the Late Preceramic Period, ca. 2500 Bc. From Grieder et al. 1988.

After 2000 BC, during the Initial Period in northern and central Peru, pottery and weaving made their first appearances, as did maize. U-shaped ceremonial centers following Late Preceramic prototypes occur in about twenty coastal sites (Williams 1985). As in the Late Preceramic, there was a continuing widespread degree of ritual and stylistic homogeneity, suggesting powerful linkages between regional populations. Very large polities appear to have been present in the Casma valley, focused on the sites of Sechin Alto and Pampa de las Llamas-Moxeke, the latter covering 220 hectares. Sechin Alto, one of the largest sites in the New World at this time, comprised a U-shaped complex 1.5 kilometers long with a central end platform 44 meters high. The modeled adobe friezes which adorn several of these sites are forebears of the famous Chavin art style which dominated the greater part of the northern Andes during the following Early Horizon.

Thus, by 2000 Bc, the northern Andes had developed large agricultural polities with populations of over 1,000 people (Burger 1992:71-72). Many chambers at La Galgada were now converted into tombs, and the wellpreserved burials indicate that about half of the population lived to over 40, and only 17.5 percent died younger than 4 years old - not a bad record for a society at this stage of cultural development. Initial Period sites extend down into the Maranon Basin in the east, giving access to the Amazonian rain forests. But it is interesting that we now witness an appearance of inter-polity warfare, graphically represented by the figures of warriors and mutilated captives carved on the blocks facing a stone platform at the coastal site of Cerro Sechin. Demographic pressures were surely building.

During the Early Horizon (900 to 200 ac), maize production increased rapidly in Peru; Ricardo Sevilla (1994) indicates that average cob lengths almost doubled between 500 Bc and AD 1. Richard Burger and Nikolaas van der Merwe (1990) note, from stable carbon isotope analysis on human bone, that maize was still not a food staple comparable to native domesticates such as potato and quinoa, and perhaps served mainly as the source for corn beer, chicha. Even so, the early part of the Early Horizon was clearly a time of considerable social stress. Michael Moseley (1994) comments on widespread site abandonment along the Peruvian coast at around 800 BC, and raises the possibility of a cause connected with environmental degradation. Shelia and Thomas Pozorski (1987) also point to the possibility of invasion around the end

of the Initial Period in parts of northern Peru, leading to some degree of population replacement via warfare. This is not the place to enter into detail about these developments, but their aftermath was the Early Horizon spread of the Chavin artistic and cult horizon over a vast area of northern and central Peru.

The site of Chavin itself perpetuated the U-shaped form of earlier periods in its Old Temple plan, but it also was clearly involved in some way in the formation of a new and remarkably complex art style which spread around 500 Be so quickly, over an area almost 1,000 kilometers long (Figure 8.4), that Peru became virtually a "religious archipelago" in Richard Burger's terms (1992:203). Communities became locked together by a powerful cult with a very standardized iconography, involving both human and feline symbolism. Chavin, of course, long postdates the origins of agriculture in the Andes, but it forms part of a long cycle of fluctuation in Peru from periods of widespread cultural homogeneity, through periods of increasing regionalism, and then back again (Burger 1992:228).

If we stand back and examine the major developments in the early agricultural sequence in the Andes, we see the following trends:

1.Once agriculture was present, developments were rapid in terms of population growth and expansion of the repertoire of domesticated products. A widespread sharing of style and iconography becomes apparent, especially in northern Peru. Varied populations doubtless took part in these developments, but within a network of communication that involved some degree of stylistic and perhaps also linguistic commonality right from the start.

2.The semi-arid environments concerned were always fragile and easily subjected to overexploitation. By 1000 BC, after a millennium of population growth during the Initial Period, warfare and site abandonment suggest that some degree of social and environmental collapse might have occurred, especially along the Pacific coast.

3.Following this, there appears to have been a reformulation of the whole system in terms of a region-wide Chavin horizon of cult, art, and exchange.

The whole Peruvian sequence so far perhaps replicates something of the sequence we see in the Levant, from early farming, through the late PPNB/PPNC decline, into the expansive early ceramic cultures of southeastern Europe and northern Mesopotamia. If my observations are not misplaced, then we need to ask just how coherently related were these Chavin populations, and indeed their immediate predecessors extending back into the Late Preceramic, in terms of language and shared aspects of cultural origin. The overall regional coherence of material culture suggests that levels of relationship in this regard would have been fairly high, more so perhaps than 2,000 years later, during the period of the Inca Empire, when we know that Peru contained some quite deep ethnolinguistic diversity. This increasing diversity over time, following on from the period of early agriculture, is beginning to follow a familiar trend, and we return to these issues from a linguistic perspective in chapter 10.