- •Summary Contents

- •Detailed Contents

- •Figures

- •Tables

- •Preface

- •The Disciplinary Players

- •Broad Perspectives

- •Some Key Guiding Principles

- •Why Did Agriculture Develop in the First Place?

- •The Significance of Agriculture vis-a-vis Hunting and Gathering

- •Group 1: The "niche" hunter-gatherers of Africa and Asia

- •Group 3: Hunter-gatherers who descend from former agriculturalists

- •To the Archaeological Record

- •The Hunter-Gatherer Background in the Levant, 19,000 to 9500 ac (Figure 3.3)

- •The Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (ca. 9500 to 8500 Bc)

- •The Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (ca. 8500 to 7000 Bc)

- •The Spread of the Neolithic Economy through Europe

- •Southern and Mediterranean Europe

- •Cyprus, Turkey, and Greece

- •The Balkans

- •The Mediterranean

- •Temperate and Northern Europe

- •The Danubians and the northern Mesolithic

- •The TRB and the Baltic

- •The British Isles

- •Hunters and farmers in prehistoric Europe

- •Agricultural Dispersals from Southwest Asia to the East

- •Central Asia

- •The Indian Subcontinent

- •The domesticated crops of the Indian subcontinent

- •The consequences of Mehrgarh

- •Western India: Balathal to jorwe

- •Southern India

- •The Ganges Basin and northeastern India

- •Europe and South Asia in a Nutshell

- •The Origins of the Native African Domesticates

- •The Archaeology of Early Agriculture in China

- •Later Developments (post-5000 ec) in the Chinese Neolithic

- •South of the Yangzi - Hemudu and Majiabang

- •The spread of agriculture south of Zhejiang

- •The Background to Agricultural Dispersal in Southeast Asia

- •Early Farmers in Mainland Southeast Asia

- •Early farmers in the Pacific

- •Some Necessary Background

- •Current Opinion on Agricultural Origins in the Americas

- •The Domesticated Crops

- •Maize

- •The other crops

- •Early Pottery in the Americas (Figure 8.3)

- •Early Farmers in the Americas

- •The Andes (Figure 8.4)

- •Amazonia

- •Middle America (with Mesoamerica)

- •The Southwest

- •Thank the Lord for the freeway (and the pipeline)

- •Immigrant Mesoamerican farmers in the Southwest?

- •Issues of Phylogeny and Reticulation

- •Introducing the Players

- •How Do Languages Change Through Time?

- •Macrofamilies, and more on the time factor

- •Languages in Competition - Language Shift

- •Languages in competition - contact-induced change

- •Indo-European

- •Indo-European from the Pontic steppes?

- •Where did PIE really originate and what can we know about it?

- •Colin Renfrew's contribution to the Indo-European debate

- •Afroasiatic

- •Elamite and Dravidian, and the Inds-Aryans

- •A multidisciplinary scenario for South Asian prehistory

- •Nilo-Saharan

- •Niger-Congo, with Bantu

- •East and Southeast Asia, and the Pacific

- •The Chinese and Mainland Southeast Asian language families

- •Austronesian

- •Piecing it together for East Asia

- •"Altaic, " and some difficult issues

- •The Trans New Guinea Phylum

- •The Americas - South and Central

- •South America

- •Middle America, Mesoamerica, and the Southwest

- •Uto-Aztecan

- •Eastern North America

- •Algonquian and Muskogean

- •Iroquoian, Siouan, and Caddoan

- •Did the First Farmers Spread Their Languages?

- •Do genes record history?

- •Southwest Asia and Europe

- •South Asia

- •Africa

- •East Asia

- •The Americas

- •Did Early Farmers Spread through Processes of Demic Diffusion?

- •Homeland, Spread, and Friction Zones, plus Overshoot

- •Notes

- •References

- •Index

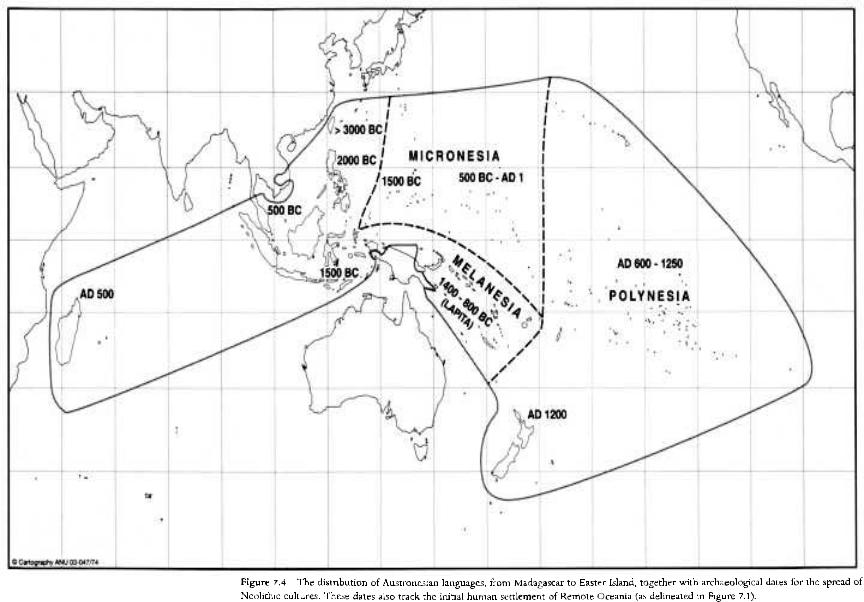

The Background to Agricultural Dispersal in Southeast Asia

To understand the creation of a human cultural kaleidoscope on the scale of Southeast Asia, we need first an awareness of some of the major environmental factors. The whole region is tropical, but there is decreasing dry season length as one moves into the equatorial zone between 5° degrees north and south, within which rain falls during much of the year (Figure 6.2). Equatorial populations tend to be small, and in eastern Indonesia often dependent for subsistence on tubers and tree crops such as yams, taro, sago, and bananas. The equatorial zone with its ever-wet rain forest is not especially suitable for rice agriculture (Figure 6.1), and in prehistoric times it would appear that rice and foxtail millet were gradually dropped from the roster of cultivated plants as agricultural populations moved through this zone and eastward into Oceania. According to Robert Dewar (2003), unreliable rainfall regimes in southern Taiwan and the northern Philippines could also have filtered out annual cereals in favor of crops with less seasonal rainfall requirements, such as taro and other tubers (see also Paz 2003). Today, and presumably also in the agricultural past, the greatest population densities occur in the monsoon regions where rainfall distribution is reliable and where rice can flourish, especially in alluvial landscapes in southern China, northern Mainland Southeast Asia, parts of the Philippines, Java, Bali, and the Lesser Sundas.

Nowhere in Southeast Asia is there currently any good evidence for a presence of any form of food production before 3500 BC. This is significant, given that rice was well domesticated by at least 6500 Bc along the Yangzi. As with the movement of agriculture from Southwestern Asia into India, so in Mainland Asia we also see an apparent slowing down, in this case apparently caused by cross-latitudinal movement and perhaps hunter-gatherer resistance, rather than by any crossing into a completely different rainfall regime (both China and Southeast Asia are part of the same monsoonal summer rainfall belt). Once on the move, however, Neolithic complexes with pottery, polished stone adzes, shell ornaments, spindle whorls, backcloth beaters, and presumeddomesticated bovids, pigs, and dogs replaced the older huntergatherer

archaeological complexes of the early and mid-Holocene with orderly precision, generally moving down a north-south axis from southern China through Mainland Southeast Asia toward the Malay Peninsula, and through Taiwan and the Philippines toward Indonesia! Within the Indonesian equatorial zone, the spread of agricultural populations was converted to a latitudinal axis out of the Borneo-SulawesiMoluccas region, on the one hand westward into western Indonesia, the Malay Peninsula, and Madagascar, and on the other hand eastward into Oceania.' The presence of an independent focus of early food production in New Guinea complicates the Oceanic story, and we return to this later.

Early Farmers in Mainland Southeast Asia

The mainland of Southeast Asia consists of upland terrain separated by a number of very long river valleys, most rising in the eastern fringes of the Himalayas and following generally north-south directions (Figure 6.3). These rivers include the Irrawaddy, the Salween, the Chao Phraya, the Mekong, and the Red (Hong), and all must have served as major conduits of human population movement in the past. Thus, it is not surprising that the Neolithic archaeology of this region shows much stronger connections with China than it does with India, an axis of relationship to be dramatically overturned at about the time of Christ with the spread of the Indic cultural influences which came to dominate the Hindu-Buddhist (pre-Islamic) civilizations of Southeast Asia. Prior to 500 BC we see very few connections between India and Southeast Asia, except for the presumed spreads westward of Austroasiatic (Munda) languages, a topic to which we return in chapter 10.

Unfortunately, the recent rather troubled history of much of Mainland Southeast Asia means that we have few data from countries such as Burma, Laos, and Cambodia. Matters are improving, but for present purposes we must rely on the richer records from Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia. In northern Vietnam, the earliest Neolithic is a little obscure with respect to origin and economic basis, as it is along the Guangdong coast. The oldest pottery in Vietnam is cord-marked, vineor basket-impressed. Because it often occurs in apparent overlap situations with Hoabinhian stone tools in caves, there has been a long-standing assumption that indigenous Hoabinhian huntergatherers might have played some role in the beginnings of agriculture in this region. This is still not well demonstrated, but there are coastal Neolithic sites such as the estuarine shell-midden at Da But and the small open site of Cai Beo which probably date to about 4500 Bc, and are thus contemporary with the oldest Guangdong Neolithic sites. Da But in particular has oval-sectioned untanged stone adzes that could be derived from Hoabinhian / Bacsonian prototypes. Charles Higham (1996a:78) notes that these sites have no certain traces of agriculture and may thus have been essentially hunter-gatherer and fishing settlements.

Apart from these early and somewhat puzzling sites, Vietnam became part of a widespread Mainland Southeast Asian Neolithic expression between 2500 and 1500 BC, an expression characterized by a distinctive style of pottery decoration comprising incised zones filled with stamped punctations, often made with a dentate or shelledge tool. Sites of this complex in the Red River Valley are attributed to the Phung Nguyen cultural complex and overlap with the development of bronze metallurgy. It is in this phase that a number of artifact types with strong southern Chinese parallels make a solid appearance. These include shouldered stone adzes, polished stone projectile points, stone bracelets and penannular earrings, and baked clay spindle whorls. More importantly, site sizes during this period became greatly increased, reaching 3 hectares in the cases of Phung Nguyen and Dong Dau. Many sites of this period (including some in southern Vietnam) have good evidence for rice cultivation from about 2000 Be onward, an economy which would have flourished on the fertile alluvial plains of the Red River (Nguyen 1998). Cattle, buffalo, and pigs might have been domesticated during the late Neolithic, but precise data are not available.

Firm data for a spread of rice agriculture by at least 2300 Bc are more clearly attested for Thailand (Glover and Higham 1996). As in northern Vietnam, the oldest pottery on the Khorat Plateau of northeastern Thailand and in the lower Chao Phraya Basin has zoned incision infilled with punctation, together with less flamboyant forms of paddle impression, including cord-marking. The former type of decoration is widespread between 2300 and 1500 Bc at sites such as Nong Nor, Khok Phanom Di, Non Pa Wai, Tha Kae, and Ban Chiang,' and we will meet it again far to the south in Malaysia. The economic record for the Thai Neolithic is especially rich, and most sites have evidence for rice cultivation from the beginning, especially in the form of husk temper in pottery. Nong Nor in central Thailand has no trace of rice at 2500 BC, but nearby and closely related Khok Phanom Di has plentiful evidence from 2000 BC onward, even though the excavators regard the rice as imported in the basal layers (Higham 2004). In northeastern Thailand, Ban Chiang has rice remains which may predate 2000 BC, but in the drier southern part of the Khorat Plateau the first agricultural sites seem to postdate 1500 Be (e.g., Ban Lum Khao in the upper Mun Valley, a west-bank tributary of the Mekong). Domestic animals include pig and dog, but neither seem to be present (except for wild pig) at Nong Nor. At Khok Phanom Di, only the dog is likely to have been

domesticated, together possibly with a species of jungle fowl. Domesticated cattle (probably of gaur or banteng ancestry) were present by at least 1500 BC in northeastern Thailand, at Non Nok Tha, Ban Lum Khao, and Ban Chiang. Domesticated water buffalo in Thailand only occur in the Iron Age, after 500 BC.

The wide distribution of the distinctive incised and zone-impressed pottery across parts of far southern China, northern Vietnam, and Thailand after about 2500 BC suggests that this region might express a similar phenomenon to that recognized in other regions of agricultural spread, namely an early homogeneity followed by a later regionalization of cultural style. Because of gaps in the record it is difficult to be certain about this, but this impression has also been remarked upon by Charles Higham (1996c). We certainly find a similar situation in the oldest Neolithic in much of Island Southeast Asia and the western Pacific, and it also becomes very apparent when we examine the oldest Neolithic complexes south of Bangkok, in Peninsular Thailand and Malaysia.

The peninsula from southwestern Thailand to Singapore is about 1,600 kilometers long and a maximum of about 300 kilometers across. It is entirely tropical, with a monsoonal summer wet season in the north, and an equatorial climate with no marked dry season in the south. The interior is mountainous, especially in Malaysia, and contains many areas of limestone with caves and rockshelters. The majority of archaeological assemblages come from cave locations, a circumstance which doubtless biases the record, but from Hoabinhian into Neolithic times there was certainly a very marked shift in cave usage from habitation to burial functions. This may reflect the arrival of agriculture, promoting a sedentary lifestyle in villages as opposed to a mobile lifestyle using temporary camps in caves.

Peninsular Neolithic pottery has cord-marked decoration, with rare incision or red-slipping, often with tripod feet or pedestals. Distinctive vessel tripods with perforations to allow hot air to escape during firing have been found in about twenty sites down almost the whole length of the peninsula, from Ban Kao in western Thailand to Jenderam Hilir in Selangor (Leong 1991; Bellwood 1993). These represent a very consistent tradition of pottery manufacture, although whether exchange or colonization, or both, can explain the widespread homogeneity is not so clear. Stephen Chia (1998) has shown that much of the Malaysian Neolithic pottery was locally made, an argument which would

support a hypothesis of colonization rather than exchange. Gua Cha in Kelantan also has fine incised pottery with zoned punctation dating to about 1000 Bc, like that discussed above from Vietnam and Thailand (Adi Taha 1985). Cemeteries of extended burials also contain (as grave goods) stone adzes with quadrangular cross-sections, some shouldered or "beaked," stone bark-cloth beaters and bracelets, bone harpoons and fishhooks, and shell beads and bracelets. Many of these artifacts are closely paralleled in the related site of Khok Phanom Di, and especially in the site of Ban Kao, in west-central Thailand, so much so that the term "Ban Kao culture" has been used to designate this peninsular complex by the excavator of Ban Kao, Per Sorensen (1967).

Sorensen had no doubt after his 1965-66 excavations at Ban Kao that the tripod pottery had an origin in "Lungshanoid China," referring at that time to the first edition (1963) of K. C. Chang's book on Chinese archaeology. Since that time, no archaeology has come to light in support of a direct derivation of the Ban Kao culture from a Neolithic assemblage in southern China, but the fact remains that the Mainland Southeast Asian Neolithic as a whole shows very marked signs of an ultimate southern Chinese inspiration. Sorensen was clearly on the right track. The Ban Kao culture represents a clear movement of Neolithic assemblages down the Malay Peninsula at about 2000-1500 BC, although south of Khok Phanom Di there is no direct archaeological evidence for rice, so the nature of the driving economy remains something of a mystery.

Summarizing the Neolithic record for the Southeast Asian Mainland, we have indications of the spread of a well-defined incised and stamped pottery style associated with rice cultivation in far southern China, Vietnam, and Thailand, between 2500 and 1500 BC. A contemporary but slightly different style of tripod pottery spread down the Malay Peninsula after 2000 BC. These spreads appear to have been rapid, extensive, and with little sign of continuity from local Hoabinhian forebears. The question remains, if there was a movement of farmers out of southern China at this time, did it occur down the major rivers, around the Vietnam coastline, or by both routes? Only future research is going to answer this question.

We must also note, finally, that some recent palynological and phytolith research hints that plant management activities combined with forest clearance might have been present well before 2500 BC on the Southeast Asian mainland

(Kealhofer 1996; Penny 1999). Forest clearance does not, of course, necessarily imply agriculture. But the possibility of a Hoabinhian focus on plant management activities long prior to the spread of formal field agriculture, probably with a strong tuber and arboricultural content, must not be overlooked. This might help to explain some of the mysteries of the oldest Neolithic in northern Vietnam referred to above, although we must remember, as we will see more clearly in Island Southeast Asia, that it is unreasonable to expect all sites with a Neolithic material culture to produce evidence for rice agriculture. The absence of rice in some Neolithic sites in Thailand, such as Nong Nor and Non Pa Wai, need not mean that the inhabitants were hunter-gatherers of Hoabinhian ancestry. Their material culture negates this entirely, and it is more likely that the "Neolithic economy" was not monolithic but flexible in differing situations.

Early Farmers in Taiwan and Island Southeast

Asia

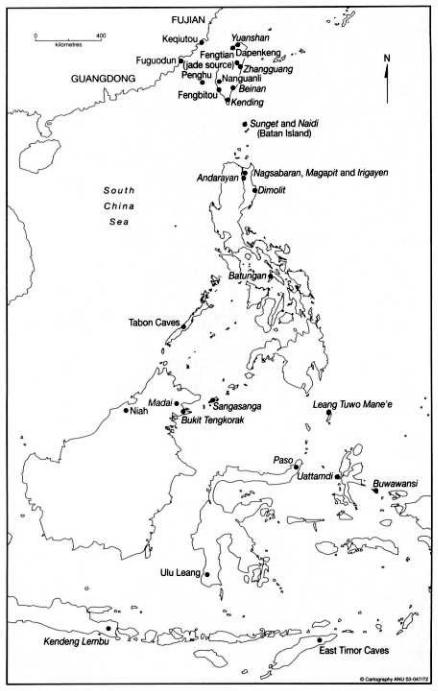

We now move southeast to the island chains which festoon the coastline of Southeast Asia. In the Taiwan archaeological record we witness the same phenomenon as in the early mainland Neolithic, namely a basal homogeneity followed by increasing regionalization. The oldest Neolithic culture in Taiwan, the Dapenkeng,s spread all round the coastline of Taiwan after 3500 BC, with a cord-marked and incised pottery style so similar everywhere that spread with a new population from Fujian replacing or assimilating the earlier Changbinian (a facies of the Hoabinhian) seems assured. Close relationships occur with slightly older Fujian pottery assemblages dating to ca. 4500 BC from sites such as Keqiutou and Fuguodun, the latter on Jinmen (Quemoy) Island.'

The Dapenkeng culture is known to have had rice and foxtail millet production, pearl shell reaping knives, spindle whorls, and barkcloth beaters, as a result of recent excavations in the twin sites of Nanguanli East and West that lie buried under 7 meters of alluvial plain near Tainan (Tsang Cheng-hwa in press). Rice is also present as impressions in sherds in a late Dapenkeng context, ca. 2500 BC, in the site of Suogang in the Penghu Islands (Tsang 1992). Furthermore, a pollen diagram from Sun-Moon Lake in the mountainous center of Taiwan indicates a marked increase in large grass pollen, second growth shrubs, and charcoal particles soon after 3000 BC (Tsukada 1967).

Following the period of the Dapenkeng culture there seems to have been internal continuity in Taiwan into the succeeding but more varied cultures of the second millennium BC. These later cultures include, amongst others, the Yuanshan in the Taipei Basin, the Niuchouzi in the southwest, and the Zhangguang and Beinan on the southeastern coast. With the passage of time, so the cultural landscape became more diversified into regional patterns. Yet, at the same time, there was also continuing contact with the Chinese mainland, as may be seen in pottery and stone tool relationships between Taiwan and contemporary mainland cultures such as the Tanshishan of northern Fujian, dating to the third and second millennia BC. Basalt from Penghu was also

widely used for adze-making in Taiwan from at least 2500 BC onward (Rolett et al. 2000).

The main point to emphasize is that the Taiwan prehistoric sequence shows no sign of an island-wide replacement of population or cultural tradition following the establishment of the Dapenkeng culture at about 3500/3000 BC. There was a relatively continuous history of cultural development into the recent ethnographic past, indicating that Austronesian-speaking populations occupied the whole island until major Chinese settlement began in the 17th century AD. It was at some point in this development, about 2500-2000 Bc according to the archaeological record, after the Dapenkeng pottery style had evolved into various regional cord-marked or red-slipped expressions, that the first Neolithic farmers moved south into the Philippines and eventually Indonesia.

Taiwan does provide one other interesting perspective on early farmers and their environmental impact. The Penghu (Pescadores) Archipelago consists of low, sandy, and fairly barren islands that lie in the Taiwan Strait, about 50 kilometers from Taiwan and 100 kilometers from the Fujian mainland. This is a dry rain-shadow area. Today, the Penghu Islands support a small population dependent on fishing and peanut cultivation, there being no good rice soils and little surface water. Field surveys and excavations here by Tsang Cheng-hwa (1992) uncovered 40 prehistoric sites, all of which dated to approximately the third millennium BC, when people grew rice (as noted above, rice impressions occur in pottery from the site of Suogang). The remaining sites belonged mainly to the period with Chinese trade ceramics during and after the Song Dynasty, starting about a millennium ago. The intervening 2,500 years would appear to be associated with no archaeological record at all.

Can we perhaps see in Penghu the results of an early collapse of an agricultural economy under conditions of high population and fairly aggressive rice cropping in a fragile environment? Such a collapse would have been localized, since no such gap is reported from anywhere on Taiwan itself, a much more fertile island. But, if this suggestion is correct there must have been repercussions for increasing agricultural investment, as in the Levantine PPNC or the late pueblo cultures of the American Southwest. It is impossible to prove that a collapse of this kind led to the movements of farming pioneers south into the Philippines, but the time and place are right in a general sense.

In the Philippines, northern Borneo, and many regions of eastern Indonesia the oldest Neolithic pottery is characterized by simple forms with plain or redslipped surfaces, sometimes with incision or stamped decoration and sometimes with perforated ring feet. This phase has no very clear internal divisions at present and it seems to date overall to between 2000 and about 500 BC, when it transforms into a series of more elaborately decorated Early Metal Phase ceramics. In the light of recent research in the Batanes Islands and the Cagayan Valley of northern Luzon, the origins of this red-slipped pottery can be traced to eastern Taiwan assemblages of about 2000 Bc, still only hazily reported but presumably the immediate ancestors of the later second millennium Beinan and Zhangguang cultures of the east coast and the Yuanshan of northern Taiwan (Figure 7.2). The Fengtian nephrite source in Eastern Taiwan was also a source of Neolithic jade (Lien 2002), used not only in Taiwan but also exported to the Philippines, where bracelets and earrings of Taiwan jade have been found in Neolithic and Early Metal Age sites (dating overall to 1500 BC to early AD) at Anaro on Itbayat Island in the Batanes, at Nagsabaran in the Cagayan Valley, and in Uyaw Cave on Palawan Island.'

Figure 7.2 Sites (in italics) that have yielded Neolithic red-slipped pottery in Island Southeast Asia.

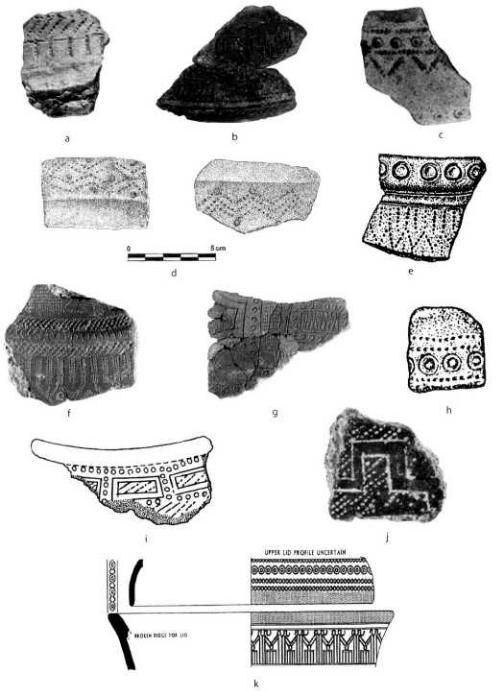

In the Philippines, this type of red-slipped pottery occurs with dentatestamped and incised motifs in the Magapit and Nagsabaran shell midden sites in the lower Cagayan Valley of northern Luzon. Dates are from 2000 BC onward

at the site of Pamittan, and some of the pottery is remarkably similar to contemporary dentatestamped pottery from the Lapita cultural complex in Melanesia and western Polynesia (Figure 7.3). Open sites at Andarayan in the Cagayan Valley and Dimolit in northeastern Luzon have yielded rice husks in sherds, dated to about 1600 Bc at Andarayan (Snow et al. 1986; Michael Graves pers. comm.). Similar pottery, but circlerather than dentate-stamped, comes from the site of Sunget on Batan Island (Batanes), where it dates from about 1200 BC (Bellwood et al. 2003).

Pottery of similar red-slipped type and second millennium Bc date to that from Luzon also comes from Bukit Tengkorak in Sabah (Bellwood and Koon 1989), here with an agate microblade industry of long drills used for shellworking, and imported obsidian carried 3500 kilometers from a source on New Britain in the Bismarck Archipelago (Figure 7.1). Bukit Tengkorak has some rather limited evidence for rice husks in pottery (Doherty et al. 2000:152), and also large quantities of fishbone and fragments of pottery stoves of a type used recently by Bajau "sea nomads" on their boats. The implication here is for a maritime economy, mobile, trade focused, with only a passing interest in field agriculture. Other assemblages with similar red-slipped pottery, but without the agate microblades and New Britain obsidian, and so far also without rice, come from northern Sulawesi, the northern Moluccas, and eastern Java (Figure 7.2). In the rockshelters of Uattamdi and Leang Tuwo Mane'e such assemblages were probably established by 1300 Bc or before. Here they also occur with polished stone adzes, shell beads and bracelets, and bones of pig and dog, none present in any older assemblages in this region (Bellwood 1997a).

The implication of all this archaeological material is that a marked cultural break with the Preceramic lithic industries of the Indonesian region occurred across a very large area, possibly commencing by 2000 BC in the Philippines and appearing close to New Guinea, after the loss of rice cultivation, by about 1400 Bc. Some of these societies had strong maritime leanings and it was probably from one or more of them that the first settlers reached the Mariana Islands in western Micronesia by 1500 Bc or before, situated across a phenomenal 2000 kilometers of open sea to the east of their likely homeland in the Philippines. By 1400 BC, culturally related colonists were also moving into Melanesia to spread the Lapita culture over 5500 kilometers eastward from the Admiralty Islands to Samoa. The Lapita movement took only 500 years or less

to reach its limits in the central Pacific, one of the fastest movements of a prehistoric colonizing population on record.

Figure 7.3 Dentate-stamped and related pottery from Island Southeast Asia and Lapita sites in Melanesia (all apart from a) are red-slipped and have lime or white clay infill in the decoration): a) Xiantouling, Guangdong coast, China

(pre-3000 Bc?); b) Magapit, Cagayan Valley, Luzon (1000 Bc); c) Yuanshan, Taipei, Taiwan (1000 Bc); d) Nagsabaran, Cagayan Valley (1500 Bc); e and h) Batungan Cave, Masbate, central Philippines (800 Bc); f) Kamgot, Anir Islands, Bismarck Archipelago (Lapita - 1300 Bc); g) Lapita (Site 13), New Caledonia (1000 Bc); i and j) Achugao, Saipan, Mariana Islands (1500 Bc); k) Bukit Tengkorak, Sabah, 1300 Bc.

All of this leads to the fairly astonishing observation that, between 2000 and 800 Bc, assemblages with related forms of red-slipped and stamped or incised pottery, shell artifacts, stone adzes, and keeping of pigs and dogs (neither of these animals being native in most of the regions concerned) spread over an area extending almost 10,000 kilometers from the Philippines through Indonesia to the western islands of Polynesia in the central Pacific. The economy driving this expansion was strongly maritime in orientation, but these people were also farmers with domesticated animals. We have no evidence that any of them grew rice in the islands beyond the Philippines and Borneo. It seems that this subtropical cereal faded from the economic repertoire as populations moved toward eastern Indonesia. In the western Pacific, however, there is good archaeological evidence from Lapita sites for production of a range of tubers and fruits, out of a roster of native plants that includes yams, aroids (especially taro), coconut, breadfruit, bananas, pandanus (a starchy fruit), canarium nuts, and many others, all originally domesticated in the tropical regions from Malaysia through to Melanesia (Kirch 1989; Lebot 1998). Neolithic populations either domesticated them, or acquired them from native populations, as they moved southward and eastward through the islands.

Meanwhile, it should be noted that the red-slipped pottery horizon does not appear in western Indonesia, although the Neolithic archaeological record here is currently only poorly understood. Most early pottery assemblages in western Borneo and Java tend to have cord-marked or paddle-impressed surface decoration without red slip. In Borneo, recent research in Kimanis Cave in East Kalimantan by Karina Arifin (pers. comm.) indicates that some sherds of this kind of pottery contain rice impressions. Similar rice impressions occur in pottery in the Niah Caves in Sarawak and in the cave of Gua Sireh near Kuching, the latter with an actual rice grain embedded in a sherd dated to about 2300 Bc by AMS radiocarbon (Ipoi and Bellwood 1991; Bellwood et al. 1992; Beavitt et al. 1996; Doherty et al. 2000). My impression from these data, still

admittedly faint and unconfirmed by any coherent information from Java or Sumatra, is that a paddle-impressed style of pottery with widespread evidence of rice spread from the Philippines, where similar impressed pottery occurs in Palawan, through Borneo and presumably into western Indonesia, after 2500 Bc. This spread was apparently independent of that which carried red-slipped pottery and a noncereal economy into the Pacific. Its source remains essentially unknown. However, the Malay Peninsula, as noted above, has a Neolithic series of assemblages derived from southern Thailand rather than from Indonesia!

Exactly how this Sundaland series of paddle impressed assemblages relates to the red-slipped pottery tradition to the east is unknown, but a homeland for both amongst populations located in Taiwan and the Philippines at about 2500/2000 BC seems likely. We seem to be looking at a geographical and economic bifurcation, the western branch emphasizing farming and open field cereal cultivation, the eastern branch trending toward a tuber and fruit (arboricultural) focus with a stronger maritime component. Pacific peoples such as the Polynesians are clearly very suitable candidates for descent from the latter tradition. But, as we will see, there is more to early agriculture in the Pacific than simple expansion from Southeast Asia.