Peptic Ulcer – Definition, Incidence, Related anatomy physiology, Etiology

Journal Published: November 14, 2014

DEFINITION

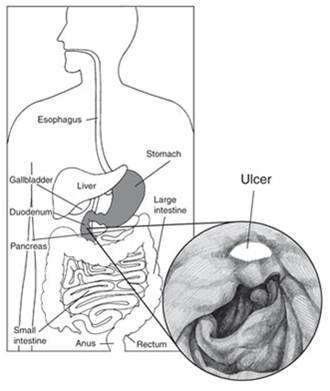

A peptic ulcer is a sore on the lining of the stomach or duodenum, the beginning of the small intestine. Less commonly, a peptic ulcer may develop just above the stomach in the esophagus, the tube that connects the mouth to the stomach.

A peptic ulcer in the stomach is called a gastric ulcer. One that occurs in the duodenum is called a duodenal ulcer. People can have both gastric and duodenal ulcers at the same time. They also can develop peptic ulcers more than once in their lifetime.

INCIDENCE

Occurrence of peptic ulcer- 4 million individuals (newcases and recurrences) affected per year. Lifetime prevalence of PUD is 12% in men and 10% in women. Moreover, an estimated 15,000 deaths per year occur as a consequence of complicated PUD.

RELATED ANATOMY

The gastric epithelial lining consists of rugae that contain microscopic gastric pits, each branching into four or five gastric glands made up of highly specialized epithelial cells. Glands within the gastric cardia comprise 5% of the gastric gland area and contain mucous and endocrine cells. The majority of gastric glands (75%) are found within the oxyntic mucosa.

Gastroduodenal Mucosal Defense

The gastric epithelium is under a constant assault by a series of endogenous noxious factors including HCl, pepsinogen/pepsin, and bile salts. In addition, a steady flow of exogenous substances such as medications, alcohol, and bacteria encounter the gastric mucosa. The mucosal defense system can be envisioned as a three-level barrier, composed of preepithelial, epithelial and subepithelial elements.

Preepithelial

Mucus

Bicarbonate

Surface active phospholipids

Epithelial

Cellular resistance

Restitution

Growth factors, Prostaglandins

Cell proliferation

Subepithelial

Blood flow

Leukocyte

PHYSIOLOGY OF GASTRIC SECRETION

Hydrochloric acid and pepsinogen are the two principal gastric secretory products capable of inducing mucosal injury.

Basal acid production occurs in a circadian pattern, with highest levels occurring during the night and lowest levels during the morning hours.

Stimulated gastric acid secretion occurs primarily in three phases based on the site where the signal originates (cephalic, gastric, and intestinal).

Sight, smell, and taste of food are the components of the cephalic phase, which stimulates gastric secretion via the vagus nerve.

The gastric phase is activated once food enters the stomach. This component of secretion is driven by nutrients (amino acids and amines) that directly stimulate the G cell to release gastrin, which in turn activates the parietal cell via direct and indirect mechanisms.

Distention of the stomach wall also leads to gastrin release and acid production. The last phase of gastric acid secretion is initiated as food enters the intestine and is mediated by luminal distention and nutrient assimilation.

Additional neural (central and peripheral) and hormonal (secretin, cholecystokinin) factors play a role in counterbalancing acid secretion. Under physiologic circumstances, these phases are occurring simultaneously.

ETIOLOGY

Family tendency

Age (between 40 to 60 years)

Gender (more in men and menopausal women)

Stress

Anxiety

Infection with gram negative bacteria H.pylori

Use of NSAIDs

Eating spicy food

Smoking and drinking alcohol

Blood group O+ve

Patients with COPD or CRF

Excessive production of hormone gastrin

CLASSIFICATION OF ULCERS

GASTRIC ULCERS

Incidence: Usually 50 and over

Male: female ratio 1:1

15% of peptic ulcers are gastric

Signs, Symptoms, and Clinical Findings

Normal—hyposecretion of stomach acid (HCl)

Weight loss may occur

Pain occurs 1⁄2 to 1 hour after a meal

may be relieved by vomiting; ingestion of food does not help, sometimes increases pain

Vomiting common

Hemorrhage more likely to occur than with duodenal ulcer; hematemesis more common than melena

Risk Factors

pylori, gastritis, alcohol, smoking, use of NSAIDs, stress

DUODENAL ULCERS

Incidence: Age 30–60

Male: female ratio 2–3:1

80% of peptic ulcers are duodenal

Signs, Symptoms, and Clinical Findings

Hypersecretion of stomach acid (HCl)

May have weight gain

Pain occurs 2–3 hours after a meal

ingestion of food relieves pain

Vomiting uncommon

Hemorrhage less likely than with gastric ulcer, but if present melena more common than hematemesis

More likely to perforate than gastric ulcers

Malignancy Possibility

Rare

Risk Factors

pylori, alcohol, smoking, cirrhosis, stress

ZOLLINGER ELLISON SYNDROME (ZES)

ZES consists of severe peptic ulcers, extreme gastric hyperacidity, and gastrin-secreting benign or malignant tumors of the pancreas.

ZES is suspected when a patient has several peptic ulcers or an ulcer that is resistant to standard medical therapy.

It is identified by the following findings: hypersecretion of gastric juice, duodenal ulcers, and gastrinomas (islet cell tumors) in the pancreas.

STRESS ULCERS

Stress ulcer is the term given to the acute mucosal ulceration of the duodenal or gastric area that occurs after physiologically stressful events, such as burns, shock, severe sepsis, and multiple organ traumas.

These are clinically different from peptic ulcer. These ulcers are most common in ventilator-dependent patients after trauma or surgery.

Fiberoptic endoscopy within 24 hours after injury reveals shallow erosions of the stomach wall; by 72 hours, multiple gastric erosions are observed. As the stressful condition continues, the ulcers spread. When the patient recovers, the lesions are reversed. This pattern is typical of stress ulceration.

Stress ulcers should be distinguished from Cushing’s ulcers and Curling’s ulcers, two other types of gastric ulcers. Cushing’s ulcers are common in patients with trauma to the brain. They may occur in the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum and are usually deeper and more penetrating than stress ulcers. Curling’s ulcer is frequently observed about 72 hours after extensive burns and involves the antrum of the stomach or the duodenum.

ESOPHAGEAL ULCERS

Esophageal ulcers occur as a result of the backward flow of HCl from the stomach into the esophagus (gastroesophageal reflux disease [GERD]).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Peptic ulcers occur mainly in the gastroduodenal mucosa because this tissue cannot withstand the digestive action of gastric acid (HCl) and pepsin.

The use of NSAIDs inhibits the secretion of mucus that protects the mucosa.

Patients with duodenal ulcer disease secrete more acid than normal, whereas patients with gastric ulcer tend to secrete normal or decreased levels of acid.

Ninety percent of tumors are found in the “gastric triangle,” which encompasses the cystic and common bile ducts, the second and third portions of the duodenum, and the neck and body of the pancreas. Approximately one third of gastrinomas are malignant.

CLINICAL MANAFESTATIONS

Abdominal discomfort is the most common symptom of both duodenal and gastric ulcers. Felt anywhere between the navel and the breastbone, this discomfort usually

is a dull or burning pain

occurs when the stomach is empty—between meals or during the night

may be briefly relieved by eating food, in the case of duodenal ulcers, or by taking antacids, in both types of peptic ulcers

lasts for minutes to hours

comes and goes for several days or weeks

Other symptoms include

weight loss

poor appetite

bloating

burping

nausea

vomiting

Some people experience only mild symptoms or none at all.

Emergency Symptoms

A person who has any of the following symptoms should call a doctor right away:

sharp, sudden, persistent, and severe stomach pain

bloody or black stools

bloody vomit or vomit that looks like coffee grounds

These “alarm” symptoms could be signs of a serious problem, such as

bleeding—when acid or the peptic ulcer breaks a blood vessel

perforation—when the peptic ulcer burrows completely through the stomach or duodenal wall

obstruction—when the peptic ulcer blocks the path of food trying to leave the stomach

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSTIC FINDINGS

Physical examination reveal pain, epigastric tenderness, abdominal distention

Blood test

Barium study of the upper GI tract

Endoscopy allows direct visualization of inflammatory changes, ulcers, and lesions. Through endoscopy, a biopsy of the gastric mucosa and of any suspicious lesions can be obtained.

X-ray studies

Stools test for occult blood

Gastric secretory studies for achlorhydria and ZES

pylori infection by biopsy and histology with culture

Urea breath tests detect the presence of Helicobacter pylori. The patient takes a capsule of carbon labeled urea and then provides a breath sample 10 to 20 minutes later. Because pylori metabolizes urea rapidly, the labeled carbon is absorbed quickly; it can then be measured as carbon dioxide in the expired breath to determine whether H. pylori is present.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

The most commonly used therapy in the treatment of ulcers is a combination of antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors and bismuth salts that suppresses or eradicates H. pylori; histamine 2 (H2) receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors are used to treat NSAID-induced and other ulcers not associated with H. pylori ulcers.

Table provides details about pharmacologic therapy

AGENT |

ACTION |

NURSING CONSIDERATION |

Antibiotics and Bismuth SaltsTetracycline (plus metronidazole)

Amoxicillin (plus clarithromycin)

Metronidazole (Flagyl); use with clarithromycin

Clarithromycin (Biaxin)

|

Exerts bacteriostatic effects to eradicate Helicobacter pylori bacteria in the gastric mucosa

A bactericidal antibiotic that assists with eradicating

An amebocide that assists with eradicating

Exerts bactericidal effects to eradicate H. pylori bacteria in the gastric mucosa

|

May cause photosensitivity reaction. Use with caution in patients with renal or hepatic impairment. Milk or dairy products may reduce medication effectiveness. May cause diarrhea. Do not use in patients allergic to penicillin.

Administer with meals to decrease GI distress. Administer with other antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors. May cause GI upset. |

Histamine 2 (H2) Receptor AntagonistsCimetidine (Tagamet)

Ranitidine (Zantac)

Famotidine (Pepcid) |

Inhibits acid secretion by blocking the action of histamine on the histamine receptors of the parietal cells in the stomach Inhibits acid secretion by blocking the action of the histamine on the histamine receptors of the parietal cells in the stomach Inhibits acid secretion by blocking the action of histamine on the histamine receptors on the parietal cells in the stomach |

May cause confusion, agitation, or coma in the elderly or those with renal or hepatic insufficiency. Long-term use may cause gynecomastia, impotence, and diarrhea. Prolonged drug half-life in patients with renal and hepatic insufficiency. Rarely causes constipation, diarrhea, dizziness, and depression. Best choice for critically ill patient Does not alter medication metabolism in the liver. Prolonged half-life in patients with renal insufficiency. Rarely causes constipation or diarrhea. |

Proton (Gastric Acid) Pump InhibitorOmeprazole (Prilosec)

Lansoprazole (Prevacid)

Rabeprazole (Aciphex)

|

Decreases gastric acid secretion by slowing the hydrogen-potassium adenosine triphosphatase (H+, K+-ATPase) pump on the surface of the parietal cells Decreases gastric acid secretion by slowing the H+, K+-ATPase pump on the surface of the parietal cells. Decreases gastric acid secretion by slowing the H+, K+-ATPase pump on the surface of the parietal cells |

Long-term use may cause gastric tumors and bacterial invasion. May cause diarrhea, additional pain, and nausea.

A delayed-release capsule that is to be swallowed whole and taken before meals.

A delayed-release tablet; swallow whole.

|

STRESS REDUCTION AND REST

• Reduce environmental stress by physical and psychological modifications as well as the aid and cooperation of family members and significant others. • The patient need help in identifying situations that are stressful or exhausting. Discourage a rushed lifestyle and an irregular schedule that may aggravate symptoms and interfere with regular meals taken in relaxed settings and with the regular administration of medications. • The patient benefit from regular rest periods during the day. • Biofeedback, hypnosis, or behavior modification may be helpful.

SMOKING CESSATION

• Smoking decreases the secretion of bicarbonate from the pancreas into the duodenum, resulting in increased acidity of the duodenum. • Continuing to smoke cigarettes may significantly inhibit ulcer repair. • Therefore, patient is strongly encouraged to stop smoking. • Smoking cessation support groups and other smoking cessation approaches are helpful.

DIETARY MODIFICATION

• Avoid extremes of temperature and overstimulation from consumption of meat extracts, alcohol, coffee (including decaffeinated coffee, which also stimulates acid • secretion) and other caffeinated beverages, and diets rich in milk and cream (which stimulate acid secretion). • Encourage three regular meals a day. • Small, frequent feedings are not necessary as long as an antacid or a histamine blocker is taken. • Eat foods that can be tolerated and avoid those that produce pain.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgery is usually recommended for patients with intractable ulcers (those that fail to heal after 12 to 16 weeks of medical treatment), life-threatening hemorrhage, perforation, or obstruction, and for those with ZES not responding to medications . Surgical procedures include vagotomy, with or without pyloroplasty, and the Billroth I and Billroth II procedures.

VAGOTOMY

Severing of the vagus nerve. Decreases gastric acid by diminishing cholinergic stimulation to the parietal cells, making them less responsive to gastrin. May be done via open surgical approach, laparoscopy or thoracoscopy

TRUNCAL VAGOTOMY

Severs the right and left vagus nerves as they enter the stomach at the distal part of the esophagus.

SELECTIVE VAGOTOMY

Severs vagal innervation to the stomach but maintains innervation to the rest of the abdominal organs.

PROXIMAL GASTRIC VAGOTOMY

Denervates acid-secreting parietal cells but preserves vagal innervation to the gastric antrum and pylorus.

PYLOROPLASTY

A surgical procedure in which a longitudinal incision is made into the pylorus and transversely sutured closed to enlarge the outlet and relax the muscle

ANTRECTOMY

Removal of the lower portion of theantrum of the stomach (which contains the cells that secrete gastrin) as well as a small portion of the duodenum and pylorus. The remaining segment is anastomosed to the duodenum (Billroth I) or to the jejunum (Billroth II).

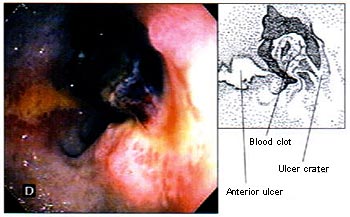

The Forrest Classification of Peptic Ulcers (Stigmata of recent haemorrhage)

Forrest 1a |

|

Forrest 1b |

Spurting bleeding |

|

Non-spurting active bleeding |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Forrest 2a |

|

Forrest 2b |

Non-bleeding visible vessel |

|

Non-bleeding ulcer with an adherent clot |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Forrest 2c |

|

Forrest 3 |

Ulcer with haematin-covered base |

|

Ulcer with clean base |

|

|

|