Introduction

Robert M. Doroghazi

Few diseases display a more dramatic and yet varied presentation than do acute aortic dissections. Onset is characteristically sudden, with severe, often unbearable pain, followed in minutes to hours by a variety of complications including cere-brovascular accident, congestive heart failure secondary to acute aortic valvular insufficiency, or cardiovascular collapse due to aortic rupture. Aortic dissection is a rapidly fatal process if not quickly recognized and meticulously managed. Early diagnosis is essential since the events which influence survival generally occur early in the course of the disease.

ANATOMY OF THE AORTA

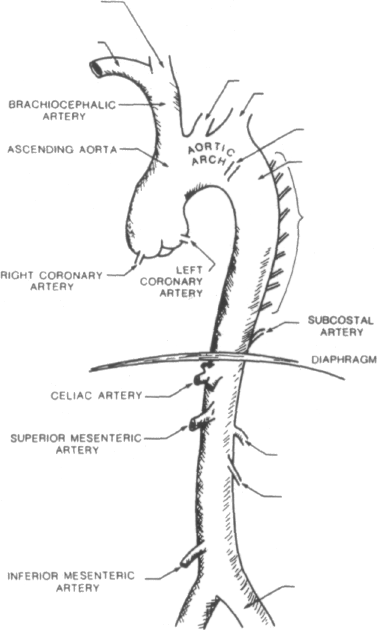

A knowledge of the anatomy of the normal aorta (Figure 1-1) is useful in enabling one to understand the classification, presentation, and methods of management of aortic dissection.

The aorta is the main trunk of the systemic arteries [1, 2]. It is approximately 3 cm in diameter at its origin. The aorta is divided into three segments: the ascending aorta, the aortic arch, and the thoracic and abdominal portions of the descending aorta.

Ascending Aorta

The ascending aorta is approximately 5 cm in length and is surrounded by the visceral pericardium. It curves obliquely to the right in the direction of the heart's axis. At its origin, the aorta is slightly dilated and is divided into three sinuses (of Valsalva) by the cusps of the aortic valve. The right and left coronary arteries arise, respectively, from the anterior and left posterior aortic sinuses. The pulmonary artery and right atrium lie anterior to the origin of the ascending aorta. The ascending aorta is flanked on its right by the superior vena cava and on its left by the pulmonary artery. Posterior to the ascending aorta lie, successively, the left atrium, the right pulmonary artery, and the right main bronchus.

Arch of the Aorta

The aortic arch is approximately 4.5 cm long and lies entirely within the superior mediastinum. The aortic arch curves upward, posterior, and leftward and terminates along the left border of the thoracic vertebra.

Three

branches of the aortic arch are, from right to left, the

brachiocephalic, left common carotid, and left subclavian arteries.

Variations of this normal branching

pattern are relatively common [3, 4] and may be of clinical

significance in

patients with aortic dissection. There are at least three case

reports [5-7] of aortic

dissection occurring in the presence of an aberrant right subclavian

artery. In this variation, the artery arises as the last branch of

the aortic arch and passes behind

the esophagus. Aortic dissection has also been reported in

association with a right-sided aortic arch [8].

Three

branches of the aortic arch are, from right to left, the

brachiocephalic, left common carotid, and left subclavian arteries.

Variations of this normal branching

pattern are relatively common [3, 4] and may be of clinical

significance in

patients with aortic dissection. There are at least three case

reports [5-7] of aortic

dissection occurring in the presence of an aberrant right subclavian

artery. In this variation, the artery arises as the last branch of

the aortic arch and passes behind

the esophagus. Aortic dissection has also been reported in

association with a right-sided aortic arch [8].

The bifurcation of the pulmonary artery, the left main bronchus, and the left recurrent laryngeal nerve lie in the concavity of the arch. The left recurrent laryngeal nerve branches from the left vagus on the anterior surface of the arch and hooks around the aorta to ascend on the posterior surface of the arch. The left lung lies on the anterior and left side of the arch and the trachea, esophagus, and thoracic duct lie posteriorly and to the right.

The ligamentum arteriosum, the obliterated remnant of the ductus arteriosus, extends from the concave side of the arch just beyond the origin of the left subclavian artery to the origin of the left pulmonary artery.

Thoracic Portion of Descending Aorta

The thoracic aorta is contained in the posterior mediastinum. It curves gradually to the right to end in the midline at the lower border of the twelfth thoracic vertebra at the aortic hiatus of the diaphragm. The thoracic aorta averages 2.3 cm in diameter at its origin and is slightly over 20 cm in length.

The most important of the many small branches of the thoracic portion of the descending aorta are the nine pairs of intercostal arteries and one pair of subcostal arteries. Of primary importance to the blood supply of the spinal cord is the artery of Adamkiewicz, whose origin is variable but generally from the lower thoracic aorta.

The root of the left lung and esophagus lie anterior and the vertebral column posterior to the aorta. The azygous vein and thoracic duct lie on the right side of the thoracic aorta, and the left lung lies on the left. The esophagus lies at first to the right, then anteriorly and then to the left of the thoracic aorta.

Abdominal Aorta

The abdominal aorta forms the continuation of the thoracic aorta. It ends at the level of the fourth lumbar vertebra, slightly to the left of the midline, by dividing into the two common iliac arteries. The average length is 15 cm. The average diameter is 20 mm at its origin and 17 mm at the lower end and is consistently larger in males than in females.

The principal branches of the abdominal aorta are the celiac, superior mesen-teric, renal, gonadal, and inferior mesenteric arteries. These vessels and the other branches of the abdominal aorta supply the splanchnic circulation and most of the lumbar portion of the vertebral column.

The anterior surface of the abdominal aorta is related to many abdominal structures, including the third part of the duodenum. Posteriorly, the aorta is separated from the lumbar vertebra by the anterior longitudinal ligament. The inferior vena cava runs on the right side of the abdominal aorta through most of its course. Structures on the left side of the aorta include the left sympathetic trunk and the ascending part of the duodenum.

DEFINITION

Aortic dissection is characterized by the development of a hematoma within the middle to outer third of the aortic media. The dissecting hematoma may extend a variable distance circumferentially, but the major dissection is usually longitudinal, paralleling the flow of blood. The separation of the aortic wall usually begins at the site of a tear involving the aortic intima and media. In 4 to 5 percent of cases no disruption of the intima can be identified [9] (see Chapters 2 and 3).

The term dissecting aneurysm (aneurysme dissequant) was originally proposed by Laennec to describe this condition [10]. An aneurysm is defined as an abnormal persistent localized dilatation of a blood vessel. In a true aneurysm, all layers of the vessel wall are included in the dilatation. In a false aneurysm, a paravascular encapsulated hematoma communicates with the lumen of a blood vessel, and the wall of the saclike structure is not composed of elements of the blood vessel wall [11]. Since this disease is not an example of either a true or false aneurysm, the term aortic dissection, or dissecting hematoma, more accurately describes the process.

Rarely, isolated dissections may arise outside the aorta. Primary dissection of the coronary arteries tends to occur in young adults and more frequently affects women, often in the postpartum period [12, 13]. Isolated dissection has also been observed in the cerebral [14], temporal [15], carotid [16], and other arteries [17].

HISTORY

Morgagni, in 1761, was probably the first to provide a clear description of aortic dissection [18]. He reported a case in which an ulceration was found approximately 2 inches above the aortic valve with the resulting hematoma having "made a way for itself into the pericardium."

One year before, in 1760, George II, king of England, died suddenly while on the commode. The autopsy, reported in 1761 by Nicholls, revealed a transverse fissure 1 to l'<4 inches long on the inner side of the aorta "through which some blood had lately passed under the external coat and formed an elevated ecchy-mosis" [19]. The autopsy also found the pericardium to be distended with a pint of coagulated blood. These findings were interpreted by Nicholls to represent the early stages of a saccular aneurysm.

Maunoir, in 1802, was the first to use the term dissection [20]. He found blood to be "dissecting throughout the circumference of the aorta." It was the French physician, Rend Laennec, who provided the term aneurysme dissequant, or dissecting aneurysm [10].

Bums in 1809 [21] and Hodgson in 1815 [22] described cases in which they found an irregular tear in the ascending aorta. The cause of death in both patients was attributed to hemopericardium. Burns also conducted experiments in which he produced dissection by injecting wax between the layers of the aortic wall in vessels where the intima seemed to be involved by the disease process.

The first cases of chronic healed dissection were described by Shekelton in 1822

[23]. In these cases he noted a reentry opening between the true and false lumens; the "double-barreled" aorta. Two years later Otto described aortic dissection in association with coarctation of the aorta in a young girl who also had a bicuspid aortic valve [24]. Elliotson in 1830 observed that the most common site of involvement was the ascending aorta [25]. He also noted that the intimal tear was usually transverse and the external tear longitudinal. The first case of aortic dissection to appear in the American literature was reported by Pennock in 1838 [26].

The first series of patients with aortic dissection was published by Peacock in 1843, who reported a total of 19 patients, including some of his own [27]. In several experiments he noted that the space formed by injecting fluid into the wall of the aorta tended to reopen into the vessel lumen. Peacock suggested that this reentry represented an "imperfect natural cure of the disease." [28],

Peacock also recognized the poor prognosis associated with dissections arising in the ascending aorta.

When the fissures were near the origin of the aorta . . . the extravasated blood readily makes its way into the sac of the pericardium ... and death is almost instantaneous.... When the fissures are situated below the arch of the aorta, the blood ... tends to separate the coats in the lower portion of the vessel and rarely makes its way to its origin; and thus the disease ... may be in no degree accessory to the patient's death [29].

Despite these vivid descriptions of the disease, it was not until 1856 that Swaine and Latham reported the first antemortem diagnosis of aortic dissection [30].

In 1863, Peacock followed his previous work with a review of 80 patients compiled from the world's literature [31 ]. He described many of the well-known features of aortic dissection including the rapidly fatal course in untreated patients, 71 percent of those for whom the time of onset was known having succumbed within 24 hours. He also noted the association between aortic dissection and both coarctation of the aorta and pregnancy and the presence of neurological signs such as hemiplegia and paraplegia.

Babes and Mironescu in 1910 suggested that an internal tear is not a necessary factor in initiating the dissecting process [32]. In 1920, Krukenberg confirmed these findings and further suggested that rupture of the vasa vasorum could initiate aortic dissection [33J.

In this century, two excellent comprehensive reviews on aortic dissection served to further define all aspects of the disease process including predisposing factors, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and outcome. In 1934, Shennan [34] analyzed 300 cases and, in 1958, Hirst, Johns, and Kime [9] reviewed a total of 505 cases.

In 1935, Gurin, Bulmer, and Derby [35J undertook the first attempt at surgical intervention in aortic dissection (Table 1-1). They created a distal reentry point in the iliac artery between the true and false lumens in an attempt to decompress the dissecting hematoma. Although initially the operation succeeded in restoring distal pulses, the patient died on the sixth postoperative day.

Paullin and James in 1948 reported that Abbott treated a patient by wrapping cellophane around a chronic dissection of the descending aorta in an attempt to dissection [41]. I'hey reasoned that the principal cause of death was not directly attributable to the intimal tear itself but rather to the forces that continue dissection, resulting ultimately in aortic rupture or compromise of flow to a vital organ. They hoped that reduction or control of these forces would result in a static or healed dissection, making possible subsequent elective surgical intervention. The use of medications to control dpi'dt (rate of rise of ventricular pressure) and blood pressure resulted in survival in six of six patients. Wheat et al. updated this experience in 1969 [44]. With medical therapy they achieved an 86 percent in-hospital survival of patients with acute aortic dissection. In 1970, Prokop et al. in an elegant series of experiments confirmed the importance of the control ofdp/dt in the extension of dissection, and justified the use of hypotensive therapy [45] (see Chapter 7).

In 1976, Slater and DeSanctis correlated the location of pain and extent of the dissecting process [46]. They reviewed the clinical characteristics of aortic dissection and emphasized the importance of clinical acumen in arriving at prompt diagnosis and treatment (see Chapter 4).

Recent series have further defined the indications for and results of medical and surgical therapy of aortic dissection including reports by McFarland et al. in 1972 [47], Reul et al. in 1975 [48], Appelbaum etal. in 1976 [49], Miller etal. in 1979 {50J, and Doroghazi et al. in 1982 [51].