- •Titles in the series include:

- •Overcoming anger and irritability a self-help guide using Cognitive Behavioral Techniques william davies

- •Isbn 978-1-84901-131-0

- •Table of contents

- •Acknowledgements

- •Introduction

- •Part one Understanding What Happens

- •What are irritability and anger?

- •What makes us angry?

- •Irritants, costs and transgressions

- •Irritants

- •Why am I not angry all the time?

- •Internal and external inhibitions

- •Inhibitions as brakes on anger

- •Constructing a system to explain irritability and anger

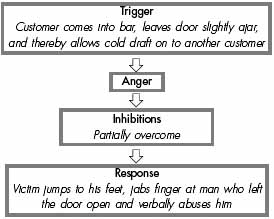

- •Figure 4.1 Kept waiting in hospital

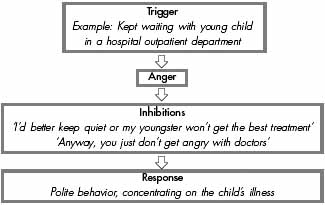

- •Figure 4.2 Mug breaks on floor

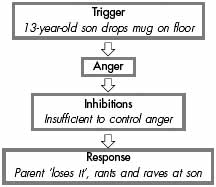

- •Figure 4.3 Door left open in bar

- •Why don’t other people feel angry at thethings that bug me?

- •Figure 5.1 Kept waiting in hospital

- •Figure 5.2 Mug breaks on floor

- •Figure 5.3 Door left open in bar

- •Why isn’t everybody irritated by the same things?

- •Figure 6.1 a model for analyzing irritability and anger

- •Why am I sometimes more irritable than at other times?

- •Figure 7.1 a model for analyzing irritability and anger

- •Is it always wrong to be angry?

- •Figure 8.1 The traditional inverted u-curve

- •Figure 8.2 Graph showing effective anger

- •Part two Sorting It Out

- •Getting a handle on the problem: The trigger

- •Figure 9.1 a model for analyzing irritability and anger

- •Why do I get angry? 1: Appraisal/judgement

- •Figure 10.1 a model for analyzing irritability and anger

- •Identify and remove ‘errors’ of judgement

- •Why do I get angry? 2: Beliefs

- •Figure 11.1 a model for analyzing irritability and anger

- •Cats, camels and recreation: Anger

- •Figure 12.1 a model for analyzing irritability and anger

- •Putting the brakes on: Inhibitions

- •Figure 13.1 a model for analyzing irritability and anger

- •Internal and external inhibitions

- •1 Steve at the bar

- •2 Ian dropping mug on floor, irritates Sue

- •3 Vicky tells of Danny and her underwear

- •4 Anne finds her daughter in the bath rather than tidying her bedroom

- •The bottom line: Response

- •Figure 14.1 a model for analyzing irritability and anger

- •‘But I’m not always irritable, just sometimes’: Mood

- •Figure 15.1 a model for analyzing irritability and anger

- •Item Average caffeine content (mg)

- •Illness

- •Testing your knowledge

- •Figure 16.1 a model for analyzing irritability and anger

- •Good Luck!

- •Appendix

- •Useful Resources

- •Institute for Behavior Therapy

Constructing a system to explain irritability and anger

The ‘leaky bucket’

If we can put all that we have worked out so far into a diagram, it will help us predict when we are going to be irritable or angry and, more to the point, prevent it happening. So let’s have a look at Figure 4.1, which summarizes what we have said so far about Judy’s case.

Figure 4.1 Kept waiting in hospital

This is actually a particularly interesting example, because many people ask: ‘What happens to the anger?’ In other words, a lot of people assume that unless you ‘get rid of’ your anger, then it somehow just builds up inside you. This is in fact the reverse of the truth. What actually happens is that the anger just gradually dissipates. The best analogy is a leaky bucket full of water. The bucket was absolutely full in this case; Judy was very angry indeed. Nevertheless, over time, all that anger just gradually seeped away, just as water seeps out of a leaky bucket, and now in the ordinary course of things she doesn’t give it a thought. (Nevertheless, if you remind her of the event, it is like pouring some more water into the bucket!)

The key concept is doing what you think is appropriate in the situation. In this case the mother judged that her behavior was indeed appropriate as her child might well have not received the best treatment if she had kicked up a fuss. So, even in retrospect, she still judges that she did right. By the same token, we get angry with ourselves when, in retrospect, we think we did not behave correctly. Again, the important concept is behaving in proportion to the situation, doing what you think is right in the particular situation. (Later on, we will look at why our judgement sometimes goes haywire so that on occasion we let ourselves down very badly.)

Figure 4.2 shows the same model applied to a different situation. The key difference is that here the inhibitions weren’t strong enough to control the level of anger experienced by Sue. The anger therefore simply overcame her inhibitions and produced a response of ‘ranting and raving’.

Figure 4.2 Mug breaks on floor

Actually, this does Sue a slight disservice. Certainly this is the way she described the incident – that she simply ‘lost it’, in other words, simply lost all control. But if that were really true, why did she not pick up the carving knife (they were in the kitchen after all) and stab her son fifty times? Clearly her inhibitions were functioning to a degree, but only at a relatively weak level; or maybe they were functioning reasonably well, but the breakage produced such an immense level of anger that they were still almost overwhelmed.

When the bucket overflows

Let’s pursue this line of thought a little further by considering the case of Steve and the door left open in the pub. This fits into our model as shown in Figure 4.3.

On the face of it, this is an accurate representation of what happened. However, if you recollect the exact situation as recounted at the beginning of Chapter 1, you will see that I have omitted the fact that this was the fifth time the door had been left slightly ajar. On each of the previous four occasions, some extra anger had been tipped into the bucket. So, by the time person number five comes along and adds his ladleful to the bucket, the whole thing is brimful and ready to overflow – and he gives five the whole bucket full of anger. You may also recollect that Steve said when he was telling the story that the ‘victim’ was quite a small man. What if he had been six feet three and built to match? Possibly that would have strengthened Steve’s inhibitions! Most people feel inhibited about picking a fight with someone twice their size.