- •Introduction

- •Foreword

- •1 Wrote the first piece without consulting him much about the content, promising him that he could see it before it was published. I had talked to him

- •In the weeks that followed, we sustained the weekly column, properly as a duet; I cannot recall who wrote what, but it was his column and I was always

- •It in front of the kitchen fire and then fill it from pans and kettles with hot water. Good place to wash your hair, Liverpool. Nice soft water.

- •It moulded us into being frightened. There was a rot which set in. They say that children will learn something if it is exciting, but when

- •In Liverpool and we are still moving in and out of happy reminiscences of childhood. He is, however, soon to leave Liverpool for the first trip to Hamburg.

- •Chapter II

- •1 A New York attorney, manager and now owner of his own record company. At the end of Brian's life, Nat was his closest friend and confidante.

- •1 Dominic Taylor, youngest son of Joan and Derek Taylor.

- •Chapter III

- •Chapter V

- •Olivia Harrison

- •Chapter VI

It moulded us into being frightened. There was a rot which set in. They say that children will learn something if it is exciting, but when

the rot sets in, you stop learning and being open to everything. That's what you have to watch. All that started when T went to the grammar school. All those logarithms, and square roots; and algebra was a terrible thing, x+3 over z =y. I would have learned Chinese or Sanskrit sooner than that. It seems to them to make sense, to the academics, the intellectuals. Algebra? 1 have no idea of what it means or where it came from. It seems to have no harmony or rhythm or basic feel because really you can understand people without knowing the same language. If you look at each other, or touch each other, you know, say have tea or something . . . and then, of course, even language can be learned. But algebra for me had nothing to do with 'reality'. I watch it now on Open University and 1 still can't connect.

Music? I even got out of music because at that point, although 1 liked music, in school it was holding your mouth like this. . . . He puckered up his mouth in a caricature of an amateur in an operetta, and continued: Well, you could play recorder or violin, and nowadays I think you can play guitars and all sorts of things, but not then.

To take the GCE (General Certificate of Education) at 16, we had first to pass three subjects in the 'mock' GCE. The first result in the 'mock' was art, which I passed. But that's because Stan Reid, the art teachet was nice, you see (he's the one with OM on his tee shirt on the Dark Horse album). Even though I wasn't that good at art, I got enough to pass the exam. I thought: 'Wow, Fantastic'.

Then the next result came. I failed, and the next. I failed, failed, failed, failed: I failed every one except art; even English Language which they had decided everyone could take regardless of what their marks had been, everyone except me! I got two per cent. Really, I didn't pass any and then they said, you can go, OK, you can go, everyone's off doing the exams,

They were ttying to put me into the next year with the class coming up behind me, to stay on and take the exams next year and I was in this class for one hour and I thought: "No thanks, squire, I'm not going to get into learning all these new people and their tricks" so I went over the railings to the movies and didn't go back until the last day to pick up my fine.

So ... I didn't have any of those things, those qualifications. What

did my parents think? They didn't know what had been said because I burned my report and testimonial. I wish I had kept them now. It-would have been interesting in retrospect to see all those teachers' signatures and what they said about me. The headmaster said: "He has taken no part in any school activity whatsoever" . . . they kept going on like that, until I felt so bad and guilty that I had to burn it before my parents got home.

Like many of the schoolboys who had grown up after the Second World George Harrison could see no meaning in army cadet corps, still flourishing in British grammar schools.

The army. The fear of the army. I had already made my mind up when I was about twelve that I was not going into the army at any cost and then at school from about thirteen years old to sixteen or seventeen they had chose cadet guys. I could never figure it out. They never actually told you, "All right. Do it." There was never any recruiting or any bulletin boards, but every Monday afternoon, or Wednesday, you would look out and see these boys and they would

all be there marching up and down with the geography teachet or the maths teacher, all dressed as soldiers, going "hup, two, three four". It's not the sort of thing you should either want to like or to dislike. It shouldn't be there! I would think "WHAT?"

] never could discover why those normal things were normal. They always seemed crazy to me: everyone acting 'normally' but it was so like The Prisoner1. You never quite know what it is they are talking about. It is like assigning your nervous system up to somebody you don't know. I always knew there was something I was not going to get from school. I knew school wasn't the be all and end all of life's opportunities. That's why it didn't bother me too much. There was always that side of me in school which thought, 'well, if that's what it is, then I don't want it'. I knew—there was something. I was fortunate enough to feel there was an alternative.

The alternative was something which became very much bigger than anyone, anyone at all, could have imagined. Yet George's optimism in the face of a depressing school-life was not a vague idea that something would turn up. He had already begun to perform musk when he was very small and in a very small way {standing on a stool) but at school he had formed an alliance with an older boy {Paul McCartney) who was one of the passengers on the daily grind of school buses.

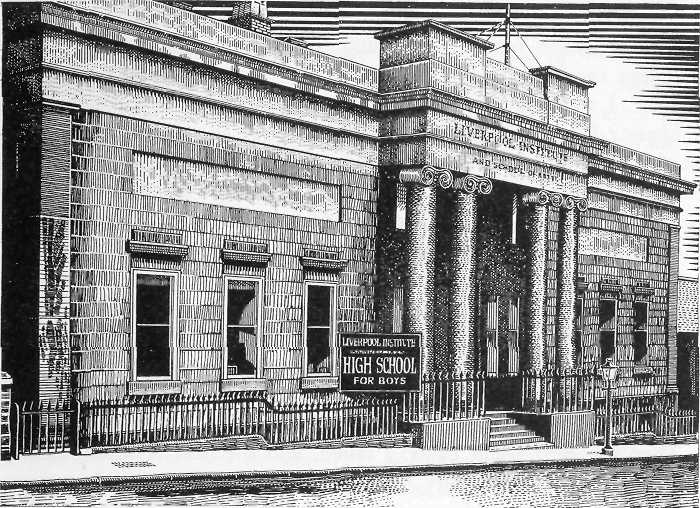

George recalls his early musical treats and influences, and painting in subdued colours pictures of Liverpool suburbanj council estate life in fascinating and occasionally excruciating detail, brings us to his meeting with McCartney {one year ahead of him at Liverpool Institute and who left one year after George, better qualified in a grammar school sense) who was quite soon to join with John Lemon in the Quarry men. They went through various combinations of names and personnel before emerging as the Beatles.

George's sister-in-law, Irene Harrison, wife of his eldest brother Harry remembers the years leading to his decision to 'have ago' at something different.

Irene was Harry's girl-friend when she first met George just after his

1 The classic Patrick McGoohan television allegory of a controlled environment. McGoohan's cry, in each of seventeen episodes; 'I am not a number. I am a free man'. It made a great impression on the Beatles and their generation.

thirteenth birthday, in 19 j6. She was seventeen then. She is still a close friend.

"The reason we hung around together was that Harry was away doing his National Service, and I suppose because I was the only child in our house, it was like having a little brother; and for George, I was maybe replacing bis older sister who had fust left home to go to Canada.

" We went out together to shows and that sort of thing. It was that rock V roll time and all the big acts, Lonnie Donegan and so on1, came to the Empire {theatre in Liverpool) and I'd get seats, and off we'd go. It was nice to have the company, you know. Then Harry and I got married and we had a flat in Liverpool and George came round there quite a bit, with Paul. Sometimes George would say 'Where are you going today?' and I would say iOh to so and so', and he'd say 'OK' and he'd go on his bike and I'd go on the bus. We got on very well together. He was a funny little fellow.

"Now he's keen on learning but everyone who wants to get out of school realises later that it was important. It depends who's teachingyou, though, and he really did hate school and he stayed off a lot. He would come round and say 'Don't tell my mum'. She used to give him his lunch money for the day and he used to waste it. I think he spent it on the pictures; he used to go to horror movies a lot, when they first came out,you know. I don't think he had very nice teachers but it is important to him to learn and everything sticks in his mind. He's lucky to have met so many people since, to learn from them. He could have left school and not gone any further.

"His mother and father were very tolerant, sensible, lovingpeople. They were so warm and brought you into everything. To go into their house was great. It was absolutely amazing. There's something about a bis. family that when you're an only one, you sort of sit back and weigh it all up. My own house was nice, always warm and kids trotting in and out but there is something about a big family. George has got a lot to thank his parents for, for the way he is today, liven up to last year'1 they .were very protective of him, because they knew he was vulnerable, a trusting soft-naturedperson. They worried a great deal about him and I don't think he knows how much. I know it's true from things they said. They worried constantly, I'm sure he was never aware of it. If he had known how much they worried about him, he'd have been amazed.

1 The Crew Cuts, Freddie Bell and Bell Boys, Frankie Lymori and ihc Teenagers, the Everly Brothers, Eddie Cochran and many others.

2 1978, when George's father died. His mother had died eight years earlier.

" Early

on, his Dad had the idea they

were all going to be . . . well, like

this: Harry was a mechanic, Pete

(George's elder brother) was a panel

beater and welder, and George was

going to be the electrician, and Dad

had the idea they'd get a garage. 1

think he was going to manage it and

have his three sons all working in

a family business. "George

blew it.

Early

on, his Dad had the idea they

were all going to be . . . well, like

this: Harry was a mechanic, Pete

(George's elder brother) was a panel

beater and welder, and George was

going to be the electrician, and Dad

had the idea they'd get a garage. 1

think he was going to manage it and

have his three sons all working in

a family business. "George

blew it.

" Dad bought him a set of electrical screwdrivers one Christmas when George was working at Blacklers and he got quite worried because he said: 'Does he want me to stick at this? I think he does'

"He came round to see us, about twenty years ago, so he must have

t' • " '" 25«SSS been sixteen, and he said he had the

— "' ■ ' - - ~ chance of being with this group and

he wanted to know what Harry thought he should do. Harry said 'Have a go',you know. 'You're still young enough to do what you want to do, if you give it a year or two, you haven't missed out.' Harry and Pete had gone into a trade, straight from school and the things they might have had in their minds to do didn't materialise, you know. George was the last one to have the opportunity to say whether he wanted to do it or not. He went off to be in the group.

"Well, you know what it was like in Liverpool; if you had a trade you were made. If you wanted to do anything else,you were a bit bonkers. I don't think our sort of upbringing allowed you to have other ideas.

"But their Mum and Dad were not the sort of people to stop their children being themselves. I remember John (Lennon) getting a flat somewhere down by Liverpool Cathedral and the idea was they were all going to live in this flat. Her (George's mother's) idea was 'You go and do it, but уоu'll be back in two

or

three weeks'—which

he was. It didn't last long, because there were no home

comforts. She was very wise."![]()

When the Harrisons moved from the cosy constrictions of Arnold Grove, it spas because their names had finally reached the top of Liverpool's still endless re-housing list. They went first to ят Upton Green, a house on an estate owned by Liverpool Corporation out at Speke. Soon after this he left the junior school in Dovedale Road near Penny Lane and went to the Institute. The bus journey took, an hour; an hour in the morning, an hour in the evening.

It took from four o'clock to five to get home in the evening to the outskirts of the Speke estate and it was on that bus journey that I met Paul McCartney, because he, being in the same school, had the same uniform and was going the same way as I was so T started hanging out with him. His mother was a midwife and he had a trumpet.

Paul, as we have learned, remained at school to take examinations, and George, dissatisfied, but confident of an alternative, left school, but not before he had expressed himself unusually, in the matter of dress.

I didn't really have money to buy clothes that meant anything but at school I did manage to get 'out there' in the last year or so when I bought a white shirt with pleats down the front, black embroidery down the corners of the pleats and a black waiter's waistcoat. It was double breasted with drape lapels and Paul had given it to me. 1 think he got it from John, who got it from his stepfather Mr. Dykins. I also had one of our Harold's sports jackets dyed black and you could still see the checkered design underneath. I wore black trousers made into drainpipes and those blue suede pointed shoes. That was how it was: pretty cheap and sloppy.

Out of school, without a direction, already playing a guitar, but not well

enough to mean much outside a close circle of'friends, George borrowed small amounts of money off his father and eventually felt bad about it.

We were playing in a band, and this went on for about eight months, borrowing ten bob off my dad, and in the end he said: "Hadn't you better get a job or something?" So I went to the Corporation (Liverpool) but 1 didn't pass the test, I wasn't even good enough to get into the 'Corpy'.

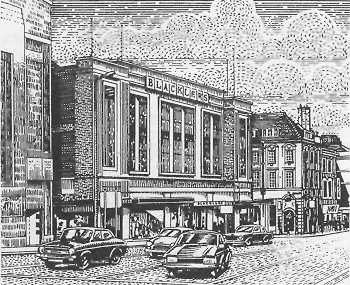

I wasn't bothering, I wasn't trying, but after a lot of time, I had to—because it was getting too embarrassing, but it was a long time before I could get a job. I went down to the Youth Employment Centre by Dale Street. The man there said "OK, there's a job as a window dresser at Bladders1," so T thought '"Why not. ГЦ do that'. It was something to do, to make everybody happy. I thought 'I'm not going to be doing it for long', but I did think T was really skiving, not having a job. When I got to Blacklcrs they had given the job away. They said: "Go and see Mr. Peet in maintenance; he's looking fot an apprentice electrician". So I got a job cleaning all the lights with a paintbrush, all those tubes to keep clean, and at Christmas T kept the grotto clean and occasionally we broke the lifts so we could have a skive in the liftshaft and then also there was darts. I learned to play darts and I learned how to drink fourteen pints of beer and three rum and blackcurrants and eat two hamburgers (Wimpy s) all in one session. All this I learned and at night we were doing gigs and we got the gig to Scotland2. 1 went and told the boss at Blacklers "I'm leaving, I'm sorry". This was great, really nice to say. Still only seventeen and I resign! They really got their money's worth out of me; they sent me off to Bootle to lay one of those big ten-phase cables in a warehouse which they owned. Thirty bob3 a week I got.

As a band, we had been playing Hoylake (over the river in the Wirral peninsula) and places like that in the evening, or at least one gig a week which would earn an extra two pounds ten shillings

1 A much loved Liverpool landmark and department store. In Liverpool all department stores are landmarks and have a personality, character, ranking, and joke-quotient of their own; Blacklcrs scores high in everythiog except snob-stams. It has always been cheerfully down-market.

2 This was a tour, regarded in Beatle-lore as a turning point, when the group backed a known singer who styled himself johnny Gentle.

3 One pound fifty pence in decimal currency.

mischief and humour, which was appreciated and encouraged. George and Derek led him astray in the best possible way and he became one of George's closest friends and confidants, especially after Derek passed away in 1997. Brian and I now share the memories of those days along with the love and respect we all had for one another.

George and Derek found hilarity concocting captions unrelated to the photos they were supposedly describing, some of which made it into the book. The photo on Plate ХХШ shows George holding his sitar, but the caption provoked letters to Genesis complaining that the reader's copy must have the wrong photos because "George is not eating a cheese sandwich with anyone in the book".

And only fans of Monty Python's Flying Circus would understand the caption to Plate XVII—an obscure reference obviously meant to be shared with those of like humour. Prinz "Walter, a Python character, had wooden teeth. Compare the smile of Britain's ex-prime minister Harold Wilson and you get the idea. First choice for the caption to Plate XLII, showing another ex-prime minister, Edward Heath, at the piano with George standing behind, was:

(George:) "Do you know your balls are hanging out?"

(Ex-prime minister Heath:) "No, but you hum it and I'll play it".

It was an old joke but Derek and George were shameless. If I put my mind to it, I can still see and hear them laughing around the kitchen table and I miss them both dreadfully along with the joy their combined humour, intelligence and affection brought into my life.

For me the essence of this book is the lyrics and I believe they stand the test of time because they are written about man's eternal quest, dilemmas, joys and sorrows. George's lyrics were, in my opinion, the most spiritually conscious of our time, although George, in turn, usually referred to the lyrics of Bob Dylan when trying to make a point or elucidate his own feelings of isolation and frustration brought about by things in and beyond this life. Many times he said, "I wish I knew more words", but perhaps all the words in the world, including the Sanskrit and mantras integral to his vocabulary, could not fully express his depth of feeling and realisation.

As I have found with other songwriters, George didn't give much away when explaining his lyrics. Wasn't it enough that he laid his emotions

and that was quite good in those days. My attitude to playing in the band was that that was the good part of life, that was what it was all about. Definitely the most pleasurable time. The people at Blacklers had known I played guitar, although I wasn't there long enough for them to know much about me. They found out about it, then they came and saw us a couple of times and then I was gone.

I have the impression that it was now grow-up-fast time. George, the failed schoolboy, the bad lad messing around at work, the scamp who knew he would be OK somehow, was becoming much more adnlt, playing rock n roll with the other lads. He went with John and Paul and Stuart Sutcliffe and Johnny Gentle to Scotland and remembers it partly as a pain in the neck.

At least we were getting famous, except it made us realise we didn't have any clothes. We looked a funny lot of buggers. We were dead rough and we were lucky to be there really, even though it wasn't very much. We travelled by van and you know there was a lot of fighting in those days, fighting for your inch. That's another thing. There's always fighting for your own space, even if it's only an inch. "Give us the credit for having an inch." So there was always a lot of that going on. That is why bands who make it rich quickly are quicker to get their own limousine. Eric wasn't with Ginger or jack1 in one car. They always had one each. I'll tell you this; if I could have afforded my own limousine, I wouldn't have gone in the van,

Now, today, if I could go on the private jet I wouldn't fly TWA. That would make everything better wouldn't it? If we could only go on the private Warner jet more often I'd give everyone concerned a free copy of this book and pay for the fuel.

Space, the importance of it, the battle for room to move and breathe and to be alone now and again, recurs in the book, as well it might. It is not a problem unique to George. But for now, in the ragged embryonic band, he is still based 1 The Cream: Eric Clapton, Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce.