- •The citole project

- •Warning: This page is horrifically graphically intensive (about 200 images at the moment). It will take a long time to load everything.

- •In Adam Davie's "Life of Alexander" from the 14th century, we read "At the feste was trumping,/ Piping and eke taborying,/ Sytolyng and eke harpyng."

- •I have a mini-lathe that I then used to turn the blocks to cut two pegs out of each one. Top here is the rough block, below is the block after being through the lathe.

- •I was happy with how it came out, and worked out the problems that I wanted to.

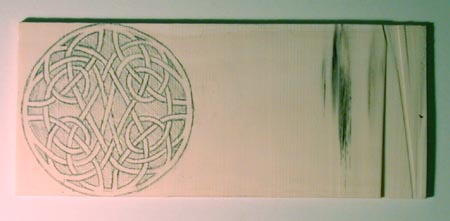

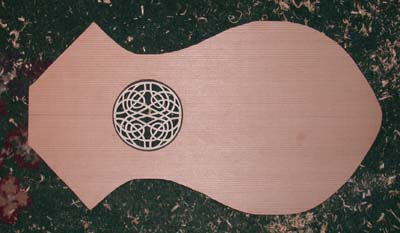

- •In the interim, working on the soundboard, since carving out the rosette takes a bit of time. This is the design for the rosette.

- •It will also have a carved pegbox with an animal head, only this time the animal will be a lion, based roughly on Celtic designs.

- •Vincenzo cipriani in Italy does another version of the cantiga style citole. See his website for more views of the instruments - very cute animal heads! No prices anywhere that I can find.

It will also have a carved pegbox with an animal head, only this time the animal will be a lion, based roughly on Celtic designs.

The

rosette will be carved into a knotwork pattern, based on a knotwork

from the Book of Kells. The idea was to have it echo somewhat the

diamond and circle pattern that appears on the back of the

instrument.

The

rosette will be carved into a knotwork pattern, based on a knotwork

from the Book of Kells. The idea was to have it echo somewhat the

diamond and circle pattern that appears on the back of the

instrument.

So

we begin. This is a nice, resonent piece of 2" thick eastern

maple that is already somewhat aged, having been in the house now for

at least a year (this was the backup piece for Citole #3 originally).

One of the most common questions I get whenever people look at Citole

one is "How long did it take you to make that?" While I

randomly guess at least several hundred hours, I actually couldn't

give people a known figure. So one of the things I decided to do with

this one is to actually calculate the amount of time it takes to do

each step. Here we've drawn the pattern carefully onto the wood. The

centerline has been marked (and will continually be re-marked to

maintain it clearly as we go along), and the area to be drilled out

eventually gridded. Total time under an hour.

So

we begin. This is a nice, resonent piece of 2" thick eastern

maple that is already somewhat aged, having been in the house now for

at least a year (this was the backup piece for Citole #3 originally).

One of the most common questions I get whenever people look at Citole

one is "How long did it take you to make that?" While I

randomly guess at least several hundred hours, I actually couldn't

give people a known figure. So one of the things I decided to do with

this one is to actually calculate the amount of time it takes to do

each step. Here we've drawn the pattern carefully onto the wood. The

centerline has been marked (and will continually be re-marked to

maintain it clearly as we go along), and the area to be drilled out

eventually gridded. Total time under an hour.

The

first wave of cutting. This is done with the larger manual saw - not

done extremely exactly, more just a gross removal of wood. The maple

is again rather harder than the cherrywood, and is a little difficult

to saw through. Total sawing time was about five hours, spread out

over a couple of nights (as my arm fatigues after about an hour).

The

first wave of cutting. This is done with the larger manual saw - not

done extremely exactly, more just a gross removal of wood. The maple

is again rather harder than the cherrywood, and is a little difficult

to saw through. Total sawing time was about five hours, spread out

over a couple of nights (as my arm fatigues after about an hour).

The

body cavity clearing is started by drilling a bunch of holes with a

1/2" bit. Like before (see above) I used the "stopper"

method to keep from drilling too deeply, but otherwise all this is

done with a hand drill (power, but not a drill press). The drilling

itself took about an hour or so, but had to be done over an evening's

time, as the drill starts to overheat if used too continuously. The

maple is, as already noted, fairly hard and the drill really has to

work to get through it. I also learned (from working on the other

citoles) that it's easier to carve out the cavity before cutting the

outer walls close - it makes the wood stronger for the harder chisel

hacking that has to be done to clear the cavity, and gives a little

possible leeway should a mistake occur.

The

body cavity clearing is started by drilling a bunch of holes with a

1/2" bit. Like before (see above) I used the "stopper"

method to keep from drilling too deeply, but otherwise all this is

done with a hand drill (power, but not a drill press). The drilling

itself took about an hour or so, but had to be done over an evening's

time, as the drill starts to overheat if used too continuously. The

maple is, as already noted, fairly hard and the drill really has to

work to get through it. I also learned (from working on the other

citoles) that it's easier to carve out the cavity before cutting the

outer walls close - it makes the wood stronger for the harder chisel

hacking that has to be done to clear the cavity, and gives a little

possible leeway should a mistake occur.

Starting

the "hacking out" of the body cavity, using the scoop

chisel and a mallet. The maple clears slower than the cherry, but

still cut pretty quickly.

Starting

the "hacking out" of the body cavity, using the scoop

chisel and a mallet. The maple clears slower than the cherry, but

still cut pretty quickly.

Finished

the first pass of clearing out the body cavity, all done with the

simple scoop chisel and mallet. This took a total of about four

hours. Now need to take the smaller chisels (and potentially the

dremel) to smooth out the walls and basically level the floor.

Neither will be finally finished until the outside carving is done,

as the thicknessing will be done from the inside.

Finished

the first pass of clearing out the body cavity, all done with the

simple scoop chisel and mallet. This took a total of about four

hours. Now need to take the smaller chisels (and potentially the

dremel) to smooth out the walls and basically level the floor.

Neither will be finally finished until the outside carving is done,

as the thicknessing will be done from the inside.

Was

finally (after much searching, as many of my regular sources have

dried up) able to secure a piece of ivory for the rosette. This nice

BIG piece came from Cue

Components, which sells billard cue making supplies.

Seemed an odd source, but they were very helpful, rather inexpensive,

and very quick. Took about 1/2 hour to transfer the pattern from

paper to the ivory and clean it up for drilling. Obviously I have

enough on this one piece to probably make another rosette!

Was

finally (after much searching, as many of my regular sources have

dried up) able to secure a piece of ivory for the rosette. This nice

BIG piece came from Cue

Components, which sells billard cue making supplies.

Seemed an odd source, but they were very helpful, rather inexpensive,

and very quick. Took about 1/2 hour to transfer the pattern from

paper to the ivory and clean it up for drilling. Obviously I have

enough on this one piece to probably make another rosette!

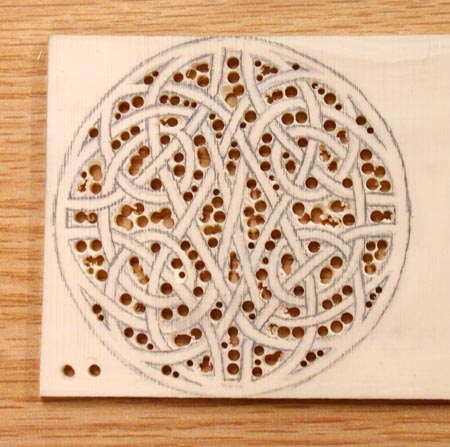

The

drilling has been done on the rosette - this took about two hours

with the dremel drill-press. Lots of little holes (no, I haven't

counted). The two holes off to the side were tests to prep lining up

the depth and targeting of the little press so I didn't damage the

primary pattern.

The

drilling has been done on the rosette - this took about two hours

with the dremel drill-press. Lots of little holes (no, I haven't

counted). The two holes off to the side were tests to prep lining up

the depth and targeting of the little press so I didn't damage the

primary pattern.

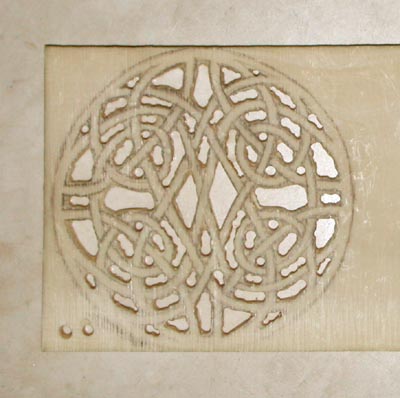

About

another two or three hours of chipping away (carefully) at the larger

spaces with the mini-chisels has basically opened up the large

spaces. The smaller spaces will then be done with the micro-chisels,

and then all of them cleaned up with the mini-files. The ivory color

is actually pretty white - it tends to look creamy or almost brown

because of the slightly odd lightening of the photos, and to help

make it more clear.

About

another two or three hours of chipping away (carefully) at the larger

spaces with the mini-chisels has basically opened up the large

spaces. The smaller spaces will then be done with the micro-chisels,

and then all of them cleaned up with the mini-files. The ivory color

is actually pretty white - it tends to look creamy or almost brown

because of the slightly odd lightening of the photos, and to help

make it more clear.

And

another two hours or so have working with the micro-chisels opens up

the remaining space. From here on out the rest of the work is done

with the mini-files to shape the holes. After that the chisels come

back to do the "knotworking" pattern.

And

another two hours or so have working with the micro-chisels opens up

the remaining space. From here on out the rest of the work is done

with the mini-files to shape the holes. After that the chisels come

back to do the "knotworking" pattern.

About

10 more hours and we have the filing done, so the sillouette is

complete. It has also been cut out (using a jeweler's saw) from the

slab and the edges evened out with the files. All that remains here

now is the over-under patterning and the ebony edging.

About

10 more hours and we have the filing done, so the sillouette is

complete. It has also been cut out (using a jeweler's saw) from the

slab and the edges evened out with the files. All that remains here

now is the over-under patterning and the ebony edging.

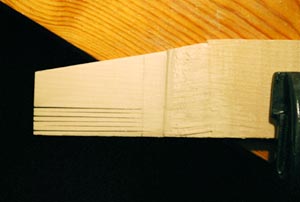

Back

on the body block, the outer edge shape has been brought closely into

line. This was done with two techniques - the first is to use a small

saw to cut a series of notches and then to chip out the spaces

between the notches (fairly quick, but risks cracking the wood). The

closer work is done with simple small chisels - see below.

Back

on the body block, the outer edge shape has been brought closely into

line. This was done with two techniques - the first is to use a small

saw to cut a series of notches and then to chip out the spaces

between the notches (fairly quick, but risks cracking the wood). The

closer work is done with simple small chisels - see below.

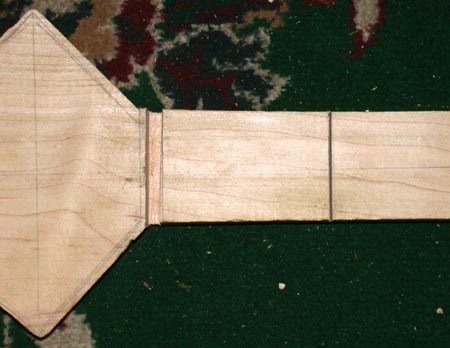

Cutting

out the neck - start by lining it out, and then cutting a notch (two

vertical cuts, with the inner space chipped out), and then using that

slot to fit in the coping saw to undercut the rest.

Cutting

out the neck - start by lining it out, and then cutting a notch (two

vertical cuts, with the inner space chipped out), and then using that

slot to fit in the coping saw to undercut the rest.

Here

you can see the technique of slowly chiseling down the surface of the

sides to bring them to just the point I want. The chisels are still

faster than filing it down, and throw a lot less dust in the air

(since I mostly work on my living room floor, this is a fairly major

consideration). You can also see here that the neck has been cut down

by this point.

Here

you can see the technique of slowly chiseling down the surface of the

sides to bring them to just the point I want. The chisels are still

faster than filing it down, and throw a lot less dust in the air

(since I mostly work on my living room floor, this is a fairly major

consideration). You can also see here that the neck has been cut down

by this point.

The

body has now been fully roughed out on the outside. That took about

eight hours of work. Next will be the cleanup of that, so I can do

the decorative carving on the outer side of the body. Once that is

down, the walls and floor will be thinned down from the inside. You

can also see the sketch of the scrollhead on the block.

The

body has now been fully roughed out on the outside. That took about

eight hours of work. Next will be the cleanup of that, so I can do

the decorative carving on the outer side of the body. Once that is

down, the walls and floor will be thinned down from the inside. You

can also see the sketch of the scrollhead on the block.

The

sides, with a combination of chisels, files and the scrapers have

been smoothed out, ready to have the drawings of the patterning done

on them. This again took about 2-3 hours per side.

The

sides, with a combination of chisels, files and the scrapers have

been smoothed out, ready to have the drawings of the patterning done

on them. This again took about 2-3 hours per side.

The

tail trefoil is carved out into its more or less final form. Not

finished - still need to final filing and sanding, but the shape is

done.

The

tail trefoil is carved out into its more or less final form. Not

finished - still need to final filing and sanding, but the shape is

done.

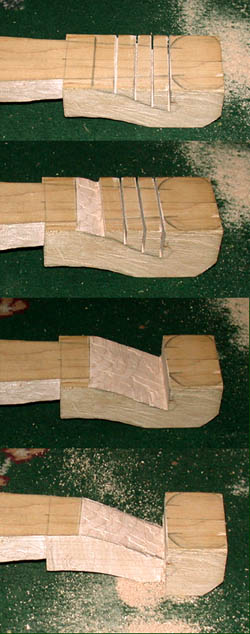

Starting

the shaping of the scrollbox. This sequence shows the rough steps I

use to work it down (similar to what I did on the sides). Use a saw

to slot the section, then a chisel to chisel out the sections between

the slots, and then saw down the sides. The area for the lion head

has been left large until I do the sculpture to see its exact

dimensions.

Starting

the shaping of the scrollbox. This sequence shows the rough steps I

use to work it down (similar to what I did on the sides). Use a saw

to slot the section, then a chisel to chisel out the sections between

the slots, and then saw down the sides. The area for the lion head

has been left large until I do the sculpture to see its exact

dimensions.

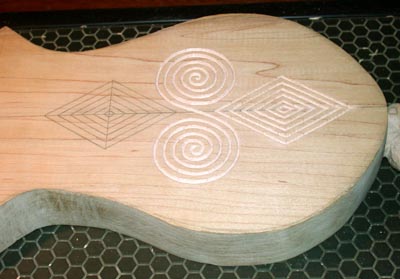

The

basic structural carving being done, I now start the surface

detailing. Here the pattern has been drawn onto the back of the

instrument.

The

basic structural carving being done, I now start the surface

detailing. Here the pattern has been drawn onto the back of the

instrument.

About

3/4ths of the way done the back pattern. The initial line is "traced"

with a sharp knife, creating an incision about 1/8 inch deep. Then a

"V" channel is chipped out using the small chisels to

either side of the line, and cleaned up with a V-chisel and the

files. I tried on some scrap using the V-chisel directly on the line,

but the changing direction of the grain, coupled especially with the

sharp curves of the spiral design, made that very awkward, and I

ended up with more mistakes than I could readily clean up. So went

with this technique instead. After the full pattern is complete,

there will be a double line done ringing the edge of the whole back,

which will be then further edged with the ebony edge-binding.

About

3/4ths of the way done the back pattern. The initial line is "traced"

with a sharp knife, creating an incision about 1/8 inch deep. Then a

"V" channel is chipped out using the small chisels to

either side of the line, and cleaned up with a V-chisel and the

files. I tried on some scrap using the V-chisel directly on the line,

but the changing direction of the grain, coupled especially with the

sharp curves of the spiral design, made that very awkward, and I

ended up with more mistakes than I could readily clean up. So went

with this technique instead. After the full pattern is complete,

there will be a double line done ringing the edge of the whole back,

which will be then further edged with the ebony edge-binding.

The

finished back carvings, though before the back has had a final

scrapping/sanding. The sides have also been finished being prepped

for having the designs drawn onto them, though still have to clean up

the neck (which will be done once I've worked out the peghead

design).

The

finished back carvings, though before the back has had a final

scrapping/sanding. The sides have also been finished being prepped

for having the designs drawn onto them, though still have to clean up

the neck (which will be done once I've worked out the peghead

design).

This

is mostly an amusement image. I sometimes get comments about how

people would like to do this kind of project, but don't have a good

workshop like I supposedly have. Well, the simple truth is I do most

of my work on my living room floor, usually while watching (or rather

mostly listening to) television. It's a nice time to catch up on all

those commentary tracks of the various DVD's I have. The 'table' is

actually my wife's Rebok Step, which I plop down in front of and work

away. My usual "live studio audience" as my wife puts it,

consists of our pet rabbits, the male Apricot of which you can see in

the background here (happily shreading the newspaper in his cage).

Peebs (our female, on the other side of the room behind the camera

from this angle) also likes to help by chewing on my projects, or

most often chewing on the tools. Apparently there is nothing more

fascinating to a rabbit than a fast moving hand saw cutting maple

wood...

This

is mostly an amusement image. I sometimes get comments about how

people would like to do this kind of project, but don't have a good

workshop like I supposedly have. Well, the simple truth is I do most

of my work on my living room floor, usually while watching (or rather

mostly listening to) television. It's a nice time to catch up on all

those commentary tracks of the various DVD's I have. The 'table' is

actually my wife's Rebok Step, which I plop down in front of and work

away. My usual "live studio audience" as my wife puts it,

consists of our pet rabbits, the male Apricot of which you can see in

the background here (happily shreading the newspaper in his cage).

Peebs (our female, on the other side of the room behind the camera

from this angle) also likes to help by chewing on my projects, or

most often chewing on the tools. Apparently there is nothing more

fascinating to a rabbit than a fast moving hand saw cutting maple

wood...

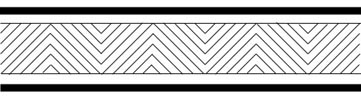

The

side carvings will be a simple matrix of alternating diagonals, lined

top and bottom with the ebony edge binding. Here is the design drawn

out before worked onto the sides of the instrument. This pattern will

run from the tailpiece to the tip of the wing on each side.

The

side carvings will be a simple matrix of alternating diagonals, lined

top and bottom with the ebony edge binding. Here is the design drawn

out before worked onto the sides of the instrument. This pattern will

run from the tailpiece to the tip of the wing on each side.

Slight

reworking of the lionhead, based on a 14th century bronze aquamarile

sculpture from the Cloisters in NYC. The person who this citole is

for preferred a closed mouth lion to an open mouthed one. Not wildly

different from the first idea, but probably in the end easier to

carve, as I won't have to do the interior of the mouth.

Slight

reworking of the lionhead, based on a 14th century bronze aquamarile

sculpture from the Cloisters in NYC. The person who this citole is

for preferred a closed mouth lion to an open mouthed one. Not wildly

different from the first idea, but probably in the end easier to

carve, as I won't have to do the interior of the mouth.

The

clay model of the lionhead, done to actual scale. As with the

greyhound head, I find it easier to carve from a 3-D model rather

than from 2-D sketches, so I make a scratch version of the carving in

clay. Obviously the detail level is rough and the mane here is merely

"suggested" rather than the actual mane, which will be a

bit fuller (I just didn't feel like wasting time building up the full

mane - was more concerned with the form of the head). The corners of

the mouth will be cut more deeply in the wood, and at this point the

intention is to inlay the eyes with ivory whites and ebony pupils.

The

clay model of the lionhead, done to actual scale. As with the

greyhound head, I find it easier to carve from a 3-D model rather

than from 2-D sketches, so I make a scratch version of the carving in

clay. Obviously the detail level is rough and the mane here is merely

"suggested" rather than the actual mane, which will be a

bit fuller (I just didn't feel like wasting time building up the full

mane - was more concerned with the form of the head). The corners of

the mouth will be cut more deeply in the wood, and at this point the

intention is to inlay the eyes with ivory whites and ebony pupils.

Working

on the neck and pegbox. This is the neck and pegbox now chiseled down

into the appropriate block size. Next is rounding out the neck and

drilling the peg holes.

Working

on the neck and pegbox. This is the neck and pegbox now chiseled down

into the appropriate block size. Next is rounding out the neck and

drilling the peg holes.

The

neck is then rounded and given a distal taper (narrows both side to

side and top to bottom as it approaches the pegbox). The point where

the neck joins the body is also smoothed out and made more crisp.

The

neck is then rounded and given a distal taper (narrows both side to

side and top to bottom as it approaches the pegbox). The point where

the neck joins the body is also smoothed out and made more crisp.

Next

I turn to the pegbox. The basic guidelines are penciled in where the

peg holes will be drilled, where the box will be hollowed, and the

centerlines for the head. The double line at the base of the pegbox

is where the nut will be going.

Next

I turn to the pegbox. The basic guidelines are penciled in where the

peg holes will be drilled, where the box will be hollowed, and the

centerlines for the head. The double line at the base of the pegbox

is where the nut will be going.

Starting

off with the head, I penciled the block design for reference from the

slightly smaller sculptural model.

Starting

off with the head, I penciled the block design for reference from the

slightly smaller sculptural model.

Carving

the headpiece. The right hand side shows where it will remain until I

do the inlay for the eyes. Some final texturing and the mane will be

detailed when I do the sanding and finishing pass after the pegbox

has been completed. Next drilling the holes and carving out the box.

Carving

the headpiece. The right hand side shows where it will remain until I

do the inlay for the eyes. Some final texturing and the mane will be

detailed when I do the sanding and finishing pass after the pegbox

has been completed. Next drilling the holes and carving out the box.

Marking

where the peg holes will be. The spacing is taken from a traditional

violin pegbox. Always makes me nervous, as I don't have a drill

press, so I'm drilling straight by eyeballing it, which doesn't leave

a lot of room for error.

Marking

where the peg holes will be. The spacing is taken from a traditional

violin pegbox. Always makes me nervous, as I don't have a drill

press, so I'm drilling straight by eyeballing it, which doesn't leave

a lot of room for error.

But

all turns out fine. Here is the finished pegbox, awaiting final

sanding and surfacing. The hollowing channel has been carved out, and

the sides thinned and straightened.

But

all turns out fine. Here is the finished pegbox, awaiting final

sanding and surfacing. The hollowing channel has been carved out, and

the sides thinned and straightened.

With

the pegbox done, it's back to the main body cavity to thin out the

walls in preparation for the fitting to the soundboard. Here you can

see the chisel-work chopping happily away at the side.

With

the pegbox done, it's back to the main body cavity to thin out the

walls in preparation for the fitting to the soundboard. Here you can

see the chisel-work chopping happily away at the side.

Before

finally thinning the walls down from the inside, I needed to do the

outer decorative carving to verify how deep it would go. The design

continues with the parallel line patterning done on the back. First

the pattern is drawn on the side, the lines of the drawing are then

cut into the wall. The lines are they chisel/chipped in so form a

cross-section V cut. And the edging is finally cut. Then I ran a

triangular small file through all the groves to smooth out as many

irregularities as I could. This process is repeated on the other

side. The design follows the curve of the body (so the grain is

constantly changing direction, making the chiseling a little

difficult). They do not "meet" in the back, as the tail

trefoil interrupts the pattern. They are skewed a little higher than

vertical center, as the soundboard will add a little thickness at the

top.

Before

finally thinning the walls down from the inside, I needed to do the

outer decorative carving to verify how deep it would go. The design

continues with the parallel line patterning done on the back. First

the pattern is drawn on the side, the lines of the drawing are then

cut into the wall. The lines are they chisel/chipped in so form a

cross-section V cut. And the edging is finally cut. Then I ran a

triangular small file through all the groves to smooth out as many

irregularities as I could. This process is repeated on the other

side. The design follows the curve of the body (so the grain is

constantly changing direction, making the chiseling a little

difficult). They do not "meet" in the back, as the tail

trefoil interrupts the pattern. They are skewed a little higher than

vertical center, as the soundboard will add a little thickness at the

top.

The

side carving done, the cavity walls can now be properly thinned down.

The gross wood removal is done with the chisels, with the final pass

(especially in the wings) using the dremel. The walls are thinned

down to about 3/16th inch thickness (to allow for the cutting in of

the sidewalls with the design). The floor has a little smoothing out

yet to do, but that will done shortly.

The

side carving done, the cavity walls can now be properly thinned down.

The gross wood removal is done with the chisels, with the final pass

(especially in the wings) using the dremel. The walls are thinned

down to about 3/16th inch thickness (to allow for the cutting in of

the sidewalls with the design). The floor has a little smoothing out

yet to do, but that will done shortly.

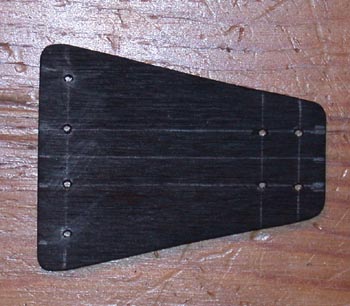

Other

bits coming together. The top image is the soundboard piece of cedar.

It will end up a bit redder when any finish is applied. The lower

piece is the bit of black (lots of glare in photo) ebony that will be

the tailpiece, fingerboard, bridge, and nut.

Other

bits coming together. The top image is the soundboard piece of cedar.

It will end up a bit redder when any finish is applied. The lower

piece is the bit of black (lots of glare in photo) ebony that will be

the tailpiece, fingerboard, bridge, and nut.

The

rough cuts of the fingerboard and tailpiece.

The

rough cuts of the fingerboard and tailpiece.

The

fingerboard has to be thinned down. The very hard ebony wood is

chiseled down (as the brightened photo here shows) and then planed

and filed smooth again to about 3/16th inch thickness.

The

fingerboard has to be thinned down. The very hard ebony wood is

chiseled down (as the brightened photo here shows) and then planed

and filed smooth again to about 3/16th inch thickness.

The

fingerboard is then centerlined, and cut to more exact shape and

length to fit the precise space of the neck of the instrument. (as

you can see, this was done before the thinning of the walls)

The

fingerboard is then centerlined, and cut to more exact shape and

length to fit the precise space of the neck of the instrument. (as

you can see, this was done before the thinning of the walls)

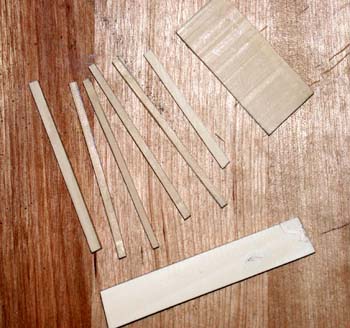

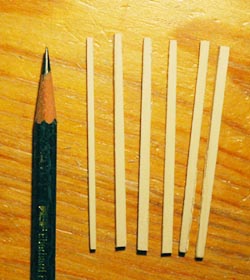

I

decided to use contrasting ivory for the frets and nut. This image

shows the frets having been rough cut (from the piece in the upper

right corner) and the chunk of ivory (old piano key rough) that will

be used for the nut.

I

decided to use contrasting ivory for the frets and nut. This image

shows the frets having been rough cut (from the piece in the upper

right corner) and the chunk of ivory (old piano key rough) that will

be used for the nut.

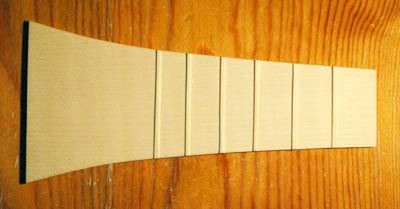

The vibrating string length will be 13.5 inches (34.3cm). Using the (now standard) six frets and the fret calculator (see above), this generates frets at 1.93cm, 3.74cm, 5.46cm, 7.08cm, 8.60cm and 10.05cm from the nut edge respectively. Next up will be to cut the grooves using the fret saw at those point, and then add in the frets.

The

distances from the nut are carefully marked on the fingerboard, and

starting slots cut into the piece with a fret saw (seen partially on

the right). The slots are then widened into a deep V shape with files

to admit the square cross-section frets (set into the fingerboard at

a 45 degree angle, so that the cross section would like like a

diamond).

The

distances from the nut are carefully marked on the fingerboard, and

starting slots cut into the piece with a fret saw (seen partially on

the right). The slots are then widened into a deep V shape with files

to admit the square cross-section frets (set into the fingerboard at

a 45 degree angle, so that the cross section would like like a

diamond).

The

frets are then evened out using the files, and then set and glued

into the slots. Overlapping end material is sawn off (using the fret

saw), and thus we have the basic fretboard.

The

frets are then evened out using the files, and then set and glued

into the slots. Overlapping end material is sawn off (using the fret

saw), and thus we have the basic fretboard.

This

is then fit and finally shaped to the actual neck of the instrument,

and is ready to be glued into place.

This

is then fit and finally shaped to the actual neck of the instrument,

and is ready to be glued into place.

Adding

the edging ring around the rosette. A strip of ebony is soaked and

steam bent into a circle just a hair smaller than the outer edge of

the ivory rosette, and allowed to dry and set in that shape (see the

mess on top). The ring is then glued together, the overlap scraped

down to a skive joint, and the inner edge filed to just admit the

ivory rosette, as shown here.

Adding

the edging ring around the rosette. A strip of ebony is soaked and

steam bent into a circle just a hair smaller than the outer edge of

the ivory rosette, and allowed to dry and set in that shape (see the

mess on top). The ring is then glued together, the overlap scraped

down to a skive joint, and the inner edge filed to just admit the

ivory rosette, as shown here.

Working

on the soundboard, the soundboard is rough cut to shape, and then

thinned down to appropriate thickness using a planing tool (I've

found that the scraper plane works better on the thin soundboard than

the finger plane I have). The piece is then scraped smooth with the

scaper, and the long sanding block is run over it to make sure that

it is flat and even along the edges where it meets the body.

Working

on the soundboard, the soundboard is rough cut to shape, and then

thinned down to appropriate thickness using a planing tool (I've

found that the scraper plane works better on the thin soundboard than

the finger plane I have). The piece is then scraped smooth with the

scaper, and the long sanding block is run over it to make sure that

it is flat and even along the edges where it meets the body.

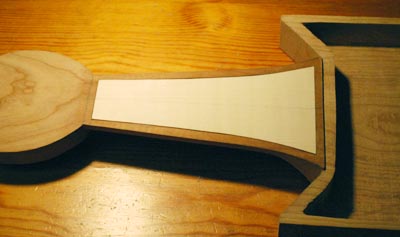

The

rough plate is then trimmed to almost exact size and lined up on the

body (it has to be matched against the fingerboard to closely seal

the top. Here you can see the slotted fingerboard (sans frets). All

of the pictures of this type of citole place the soundhole at more or

less the thinnest part of the body, so that is where I centered the

hole. The actual circle is traced around the finished edged rosette.

The

rough plate is then trimmed to almost exact size and lined up on the

body (it has to be matched against the fingerboard to closely seal

the top. Here you can see the slotted fingerboard (sans frets). All

of the pictures of this type of citole place the soundhole at more or

less the thinnest part of the body, so that is where I centered the

hole. The actual circle is traced around the finished edged rosette.

The

soundhole is then cut out (using a minature hand saber saw) and filed

to match the shape of the rosette as exactly as possible (mostly by

fitting it against the hole, seeing where there is overlap, filing

out the overlap, refitting it, etc.). When the hole is finally as

close as I can get it, the rosette is glued into place.

The

soundhole is then cut out (using a minature hand saber saw) and filed

to match the shape of the rosette as exactly as possible (mostly by

fitting it against the hole, seeing where there is overlap, filing

out the overlap, refitting it, etc.). When the hole is finally as

close as I can get it, the rosette is glued into place.

The

soundboard brace is then set. This is fit under the soundboard

between the soundhole and the bridge. Generally I've found that the

body is small enough that it really only needs the single brace at

the widest part of the lower bout just to avoid sag in the soundboard

from the pressure of the bridge. The brace is cut from a piece of

spruce, and is shaped to a tapered T intersection. It is then test

fitted (to make sure it doesn't bump the inner walls of the body),

and then glued into place.

The

soundboard brace is then set. This is fit under the soundboard

between the soundhole and the bridge. Generally I've found that the

body is small enough that it really only needs the single brace at

the widest part of the lower bout just to avoid sag in the soundboard

from the pressure of the bridge. The brace is cut from a piece of

spruce, and is shaped to a tapered T intersection. It is then test

fitted (to make sure it doesn't bump the inner walls of the body),

and then glued into place.

Back

to the main body. Now that the basics of the body are done, the

edging of the lower side should be done before the top is assembled,

as I will have to have the instrument upsidedown for most of that

process, and didn't want to damage the rosette or fingerboard in the

process. The edge binding is done in black ebony strips about 1/4

inch wide and 1/8 thick. First step is to cut a channel around the

bottom to accept the edgeing. This is done with a routing attachment

on the dremel (see above).

Back

to the main body. Now that the basics of the body are done, the

edging of the lower side should be done before the top is assembled,

as I will have to have the instrument upsidedown for most of that

process, and didn't want to damage the rosette or fingerboard in the

process. The edge binding is done in black ebony strips about 1/4

inch wide and 1/8 thick. First step is to cut a channel around the

bottom to accept the edgeing. This is done with a routing attachment

on the dremel (see above).

Next

the strips are bent into shape using a bending iron (seen here more

or less center). The wood is wet down and slowly pressured under heat

to accept the new shape. Unfortunately this edging is quite thick.

The curves aren't really hard (like in the citoles one and three,

both of which had sharp curves), but the thicker wood was harder to

bend and required a bit of practice to get to work. The fret saw is

also visible here as I trimmed excess length from the strips to get

them to fit together more exactly.

Next

the strips are bent into shape using a bending iron (seen here more

or less center). The wood is wet down and slowly pressured under heat

to accept the new shape. Unfortunately this edging is quite thick.

The curves aren't really hard (like in the citoles one and three,

both of which had sharp curves), but the thicker wood was harder to

bend and required a bit of practice to get to work. The fret saw is

also visible here as I trimmed excess length from the strips to get

them to fit together more exactly.

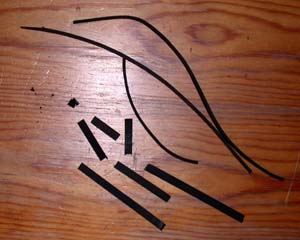

In

the "it's never as easy as it looks" concept - these are

the failed attempts to bend the wood. Most of the little pieces are

the bits that snapped off as I was trying to bend the first curve.

The long strips made it past the first curve, but tended to crack or

snap in the second curve or in fine tuning of the shape. Some of the

longer straight bits were able to be salvaged for the straight lines

of the edges. Most however were too short. Ah, practice makes

perfect. Or at least workable.

In

the "it's never as easy as it looks" concept - these are

the failed attempts to bend the wood. Most of the little pieces are

the bits that snapped off as I was trying to bend the first curve.

The long strips made it past the first curve, but tended to crack or

snap in the second curve or in fine tuning of the shape. Some of the

longer straight bits were able to be salvaged for the straight lines

of the edges. Most however were too short. Ah, practice makes

perfect. Or at least workable.

Gluing

the bottom edge binding into place. This involves a lot of cloth-tape

and "citole bondage" as my wife calls it. The edge binding

pieces are actually first fitted carefully all into place, and the

edges trimmed and shaped so that they all fit as exactly as possible.

(the brush, by the way, is for rapid spreading of the glue into the

corners of the edging shelf - my fingers are too thick to fit into

the small space).

Gluing

the bottom edge binding into place. This involves a lot of cloth-tape

and "citole bondage" as my wife calls it. The edge binding

pieces are actually first fitted carefully all into place, and the

edges trimmed and shaped so that they all fit as exactly as possible.

(the brush, by the way, is for rapid spreading of the glue into the

corners of the edging shelf - my fingers are too thick to fit into

the small space).

The

binding bits all glued into place. They are taller and thicker than

necessary, and need to be trimmed down. This is done with chisels and

files.

The

binding bits all glued into place. They are taller and thicker than

necessary, and need to be trimmed down. This is done with chisels and

files.

Bottom

binding is now done. The dark "staining" is actually ebony

dust that needs to be cleaned off. Otherwise we're good to go for

assembly.

Bottom

binding is now done. The dark "staining" is actually ebony

dust that needs to be cleaned off. Otherwise we're good to go for

assembly.

Working

on the pegbox and figurehead. First the neck (now that the

fingerboard has been fitted against it) was a little thick, so it was

thinned down and the angle readjusted. Then the pegbox itself was

softened and shaped. The wedge-space where the box meets the neck is

rounded sort of into the shape like a violin neck, and the sweep of

the box is cleaned up.

Working

on the pegbox and figurehead. First the neck (now that the

fingerboard has been fitted against it) was a little thick, so it was

thinned down and the angle readjusted. Then the pegbox itself was

softened and shaped. The wedge-space where the box meets the neck is

rounded sort of into the shape like a violin neck, and the sweep of

the box is cleaned up.

Doing

the final carving on the figurehead. The rough-carved lion's face is

smoothed out and rounded where needed. Shown here is working on the

mane- the penciled in guidelines for cutting and shaping.

Doing

the final carving on the figurehead. The rough-carved lion's face is

smoothed out and rounded where needed. Shown here is working on the

mane- the penciled in guidelines for cutting and shaping.

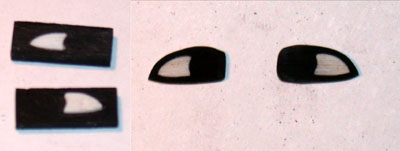

The

figurehead carving done, I had decided to do inlay for the eyes. The

idea was to have a base ebony piece and inlay the "white"

of the eye with a small piece of ivory. Shown here are the little

chunks of ivory and the scrap bit they were cut from, the strip of

ebony I was using for the bases, the micro-needle files, the little

pencil plan, and a tiny pair of needle-pliers to hold things while I

was working on them. For scale, the ebony strip is 1/4" across.

The

figurehead carving done, I had decided to do inlay for the eyes. The

idea was to have a base ebony piece and inlay the "white"

of the eye with a small piece of ivory. Shown here are the little

chunks of ivory and the scrap bit they were cut from, the strip of

ebony I was using for the bases, the micro-needle files, the little

pencil plan, and a tiny pair of needle-pliers to hold things while I

was working on them. For scale, the ebony strip is 1/4" across.

The

little tiny bits of ivory were shaped with the microfiles, and then

very small shallow holes were cut into the ebony strip. The blocks

were then cut from the strip, and the micro-files shaped the outside

of the ebony into the rough eye-shapes. The outer edge was left

larger in this picture than it finally ended up.

The

little tiny bits of ivory were shaped with the microfiles, and then

very small shallow holes were cut into the ebony strip. The blocks

were then cut from the strip, and the micro-files shaped the outside

of the ebony into the rough eye-shapes. The outer edge was left

larger in this picture than it finally ended up.

The

final figurehead with the eyes inlaid, from front side and back

views. Came out rather well I think.

The

final figurehead with the eyes inlaid, from front side and back

views. Came out rather well I think.

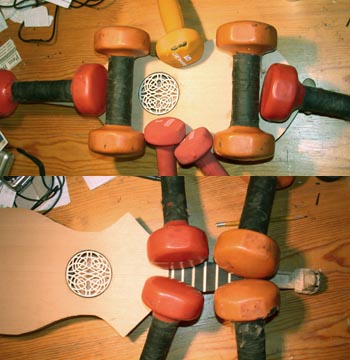

Now

that all the bottom binding is on and the peghead finished, most of

the "rough" handling of the body block is done. I didn't

want to add on the rather delicate soundboard until I was done with

the twisting and turning and such of the body block necessary to do

the bottom binding and the carving of the figurehead, etc. With that

all finished, the soundboard and fingerboard are carefully test fit

and any issues of that cleaned up, and then both are glued down in

succession (soundboard first, as it is easier to read the placement

off the light soundboard wood rather than the dark ebony). Once again

I used the standard "handweight press" method of gluing.

Now

that all the bottom binding is on and the peghead finished, most of

the "rough" handling of the body block is done. I didn't

want to add on the rather delicate soundboard until I was done with

the twisting and turning and such of the body block necessary to do

the bottom binding and the carving of the figurehead, etc. With that

all finished, the soundboard and fingerboard are carefully test fit

and any issues of that cleaned up, and then both are glued down in

succession (soundboard first, as it is easier to read the placement

off the light soundboard wood rather than the dark ebony). Once again

I used the standard "handweight press" method of gluing.

Once

the glue has set, the soundboard is cleaned up around the edges (I'd

just changed the gerbil cages with cedar wood, and the filing of the

aged cedarwood top filled the whole room with cedar smell) and the

fingerboard is likewise cleaned up with the already thinned down

neck. The only thing left now on the body block is the top

edgebinding.

Once

the glue has set, the soundboard is cleaned up around the edges (I'd

just changed the gerbil cages with cedar wood, and the filing of the

aged cedarwood top filled the whole room with cedar smell) and the

fingerboard is likewise cleaned up with the already thinned down

neck. The only thing left now on the body block is the top

edgebinding.

Not

to be too repetitive here, but this is the top bit edge binding

channel cut, and then the bent side pieces roughly in set. Since I

had such a hard time bending the bottom pieces, which when placed

turned out to be twice as thick as they needed to be, I decided to

sand these down to about the right thickness BEFORE I bent them,

which made the bending process much, much easier this time around.

The top has five pieces - the two straight sides at the front, the

two long bent sides, and the end saddle piece (a little thicker than

the simple edgebinding to hold the stress of the tailgut).

Not

to be too repetitive here, but this is the top bit edge binding

channel cut, and then the bent side pieces roughly in set. Since I

had such a hard time bending the bottom pieces, which when placed

turned out to be twice as thick as they needed to be, I decided to

sand these down to about the right thickness BEFORE I bent them,

which made the bending process much, much easier this time around.

The top has five pieces - the two straight sides at the front, the

two long bent sides, and the end saddle piece (a little thicker than

the simple edgebinding to hold the stress of the tailgut).

What

my wife likes to refer to as "citole bondage." The

edgebinding put on - top shows the top edge going on. The nice

cross-hatch pattern is the two front straight pieces, and the last

image shows the saddle piece being held in place. For the last I used

tension similar to the way it will actually be stressed by the

tailgut to hold it in place.

What

my wife likes to refer to as "citole bondage." The

edgebinding put on - top shows the top edge going on. The nice

cross-hatch pattern is the two front straight pieces, and the last

image shows the saddle piece being held in place. For the last I used

tension similar to the way it will actually be stressed by the

tailgut to hold it in place.

The

top edge binding is then cut and filed down to be flush with the

body, and the saddle shaped and filed as well. That completes the

construction of the body block.

The

top edge binding is then cut and filed down to be flush with the

body, and the saddle shaped and filed as well. That completes the

construction of the body block.

However

one more part must be done before can delve into final sanding, and

that is cleaning up and finishing the pegbox. For that I need the

pegs. Here is a roughed out peg (technically after shaving, they

start out more straight edged and less tapered) in ebony. Using the

triangular shaped heads to continue to match the angular designs

covering most of the instrument.

However

one more part must be done before can delve into final sanding, and

that is cleaning up and finishing the pegbox. For that I need the

pegs. Here is a roughed out peg (technically after shaving, they

start out more straight edged and less tapered) in ebony. Using the

triangular shaped heads to continue to match the angular designs

covering most of the instrument.

There

are two specialized tools used when doing the peg shaping - one is

called a peg reamer and other a peg shaver. They both have to match

rather exactingly in angle for the pegs to fit well into the holes.

The reamer creates a tapered hole, and the shaver carves down the peg

shaft to match that taper. Here is shown the peg shaver (and lots of

shavings) with a peg.

There

are two specialized tools used when doing the peg shaping - one is

called a peg reamer and other a peg shaver. They both have to match

rather exactingly in angle for the pegs to fit well into the holes.

The reamer creates a tapered hole, and the shaver carves down the peg

shaft to match that taper. Here is shown the peg shaver (and lots of

shavings) with a peg.

Fitting

the pegs correctly is a kind of back and forth process between

fitting and then shaving, until they sit at the desired depth. The

holes are cut as wide as tolerable to the pegbox without weakening

the walls too much. As each hole is not exactly the same (they tend

to get narrower toward the lionhead), and each peg length isn't

identicle (the pegs get shorter toward the lionhead as the pegbox

gets narrower), each peg is fit specifically to it's individual hole.

Here are the pegs (still haven't been finally finished) in place. The

overhanging shafts will be trimmed down so that they don't stick as

much out of the opposite side when I finish each peg.

Fitting

the pegs correctly is a kind of back and forth process between

fitting and then shaving, until they sit at the desired depth. The

holes are cut as wide as tolerable to the pegbox without weakening

the walls too much. As each hole is not exactly the same (they tend

to get narrower toward the lionhead), and each peg length isn't

identicle (the pegs get shorter toward the lionhead as the pegbox

gets narrower), each peg is fit specifically to it's individual hole.

Here are the pegs (still haven't been finally finished) in place. The

overhanging shafts will be trimmed down so that they don't stick as

much out of the opposite side when I finish each peg.

The

body block is now done, and final sanding smooths out all the

scratches and such. There are a couple of small imperfections which

are cleaned up with wood putty or little grafts, to maintain the

clean lines.

The

body block is now done, and final sanding smooths out all the

scratches and such. There are a couple of small imperfections which

are cleaned up with wood putty or little grafts, to maintain the

clean lines.

Doing

the lacquer finishing on the instrument. Like with my own instrument

(the highly carved one up above), I'm using a violin oil varnish from

the International Violin Company for the finish (as I liked the way

it worked on both the rebec and the other citole, and has held up

well on both unlike the linseed oil finish which really needs

retouching on the dog-headed citole). The oil varnish dries rather

slowly. This has the advantage that it makes it easier to apply (the

spirit varnish is drying practically as you are using it), but has

the disadvantage that it takes a day or two between each coat for it

to dry, making the multiple coats a very slow process. The local

weather here (suddenly very cold and damp) has slowed that even more

(as it doesn't dry as quickly in the cold damp air, and I have to

leave windows open in the room as I don't have any real ventilation

equipment and don't particularly feel like having my entire apartment

smell like oil paint!). The maple, like with my other instrument,

came out a very nice golden color. The Cedar is a little darker and

redder, and I think will probably redden to almost a cherry color as

soon as it sees sunlight. The ivory rosette now stands out VERY

brightly.

Doing

the lacquer finishing on the instrument. Like with my own instrument

(the highly carved one up above), I'm using a violin oil varnish from

the International Violin Company for the finish (as I liked the way

it worked on both the rebec and the other citole, and has held up

well on both unlike the linseed oil finish which really needs

retouching on the dog-headed citole). The oil varnish dries rather

slowly. This has the advantage that it makes it easier to apply (the

spirit varnish is drying practically as you are using it), but has

the disadvantage that it takes a day or two between each coat for it

to dry, making the multiple coats a very slow process. The local

weather here (suddenly very cold and damp) has slowed that even more

(as it doesn't dry as quickly in the cold damp air, and I have to

leave windows open in the room as I don't have any real ventilation

equipment and don't particularly feel like having my entire apartment

smell like oil paint!). The maple, like with my other instrument,

came out a very nice golden color. The Cedar is a little darker and

redder, and I think will probably redden to almost a cherry color as

soon as it sees sunlight. The ivory rosette now stands out VERY

brightly.

While

the finishing is going on, working on the small bits so that the

strings can go on right as that part is done. Here are the nut and

bridge roughed out. The nut is ivory (to match the frets), and the

bridge ebony. The bridge also has a tapered T cross-section. I will

also probably carve out some of the middle (making two "feet")

to lighten it up a bit as it is a little heavy.

While

the finishing is going on, working on the small bits so that the

strings can go on right as that part is done. Here are the nut and

bridge roughed out. The nut is ivory (to match the frets), and the

bridge ebony. The bridge also has a tapered T cross-section. I will

also probably carve out some of the middle (making two "feet")

to lighten it up a bit as it is a little heavy.

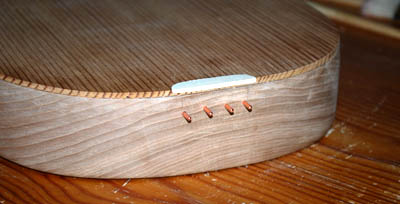

The

last piece (short of the strings themselves) is the tailpiece, which

has been roughed out here. Clearly visible on this picture are the

guidelines for drilling the holes. The holes are initially drilled

with tiny manual finger drills to place them as exactingly as

possible (I don't have a drill press), and then widened first with

bigger finger drills, and then with files until the string that needs

to go through them can slip through without any snagging. The

tailpiece will also get a bit of ivory inlay design.

The

last piece (short of the strings themselves) is the tailpiece, which

has been roughed out here. Clearly visible on this picture are the

guidelines for drilling the holes. The holes are initially drilled

with tiny manual finger drills to place them as exactingly as

possible (I don't have a drill press), and then widened first with

bigger finger drills, and then with files until the string that needs

to go through them can slip through without any snagging. The

tailpiece will also get a bit of ivory inlay design.

The

tailpiece prepped for the ivory inlay - the channels for the ivory

have been cut into the thin piece using the small chisels and are now

ready for the application of the little ivory bits.

The

tailpiece prepped for the ivory inlay - the channels for the ivory

have been cut into the thin piece using the small chisels and are now

ready for the application of the little ivory bits.

The

little ivory bits! These are about 1/16 of an inch wide and very

thin. The LONG pieces here are about 3/4th of an inch. I actually

have to use mini-pliers to handle them, as my fingers are too big to

hold them and work on them.

The

little ivory bits! These are about 1/16 of an inch wide and very

thin. The LONG pieces here are about 3/4th of an inch. I actually

have to use mini-pliers to handle them, as my fingers are too big to

hold them and work on them.

The

idea was to cut square channels and pressure fit the ivory inlays

into them. Unfortunately, during one of the pressure fits, the

tailpiece itself snapped in half. While rather annoying, I imagine

it's better this happened now than when I was tightening up the

strings and it trashed the face of the instrument. Ah well, back to

the drawing board...

The

idea was to cut square channels and pressure fit the ivory inlays

into them. Unfortunately, during one of the pressure fits, the

tailpiece itself snapped in half. While rather annoying, I imagine

it's better this happened now than when I was tightening up the

strings and it trashed the face of the instrument. Ah well, back to

the drawing board...

The little ivory bits! These are about 1/16 of an inch wide and very thin. The LONG pieces here are about 3/4th of an inch. I actually have to use mini-pliers to handle them, as my fingers are too big to hold them and work on them.

The

new tailpiece. Presently this is about 1/4 of an inch thick (rather

than the 1/8 that the other tailpiece was). I'll probably leave it a

little thicker overall, and will add the inlay in first before I thin

it down.

The

new tailpiece. Presently this is about 1/4 of an inch thick (rather

than the 1/8 that the other tailpiece was). I'll probably leave it a

little thicker overall, and will add the inlay in first before I thin

it down.

Even

so, don't want a repeat of the previous disaster. So decided to try a

different method - this time cutting V-grooves and inserting the

diamond cross-sectioned ivory rods into the grooves, much like

miniature versions of the frets. This little test sample (long side

is 1/2 inch) worked very well and was quite a bit faster as I did not

have to get the width of the ivory as exact (the wedge shape just

fills the V-groove as far down as it can - the width of the groove

determines the width of the sanded down piece). In any event, I'll

proceed to do the inlay on the new tailpiece using that method.

Even

so, don't want a repeat of the previous disaster. So decided to try a

different method - this time cutting V-grooves and inserting the

diamond cross-sectioned ivory rods into the grooves, much like

miniature versions of the frets. This little test sample (long side

is 1/2 inch) worked very well and was quite a bit faster as I did not

have to get the width of the ivory as exact (the wedge shape just

fills the V-groove as far down as it can - the width of the groove

determines the width of the sanded down piece). In any event, I'll

proceed to do the inlay on the new tailpiece using that method.

In

the meantime, the rest of the fitting are finished. Here you can see

examples of the rough carved peg (bottom) and the finished shape. All

four pegs are now finished and oiled. They will be drilled and cut to

length during the stringing set-up. The bridge and nut likewise are

fully shaped, and merely awaiting the string set-up for fine tuning.

I decided to redesign the bridge a bit, giving it short feet with a

small cutout in the center. All of it is now just waiting on the

tailpiece, as the body block is complete - the last coat of varnish

is dry and polished.

In

the meantime, the rest of the fitting are finished. Here you can see

examples of the rough carved peg (bottom) and the finished shape. All

four pegs are now finished and oiled. They will be drilled and cut to

length during the stringing set-up. The bridge and nut likewise are

fully shaped, and merely awaiting the string set-up for fine tuning.

I decided to redesign the bridge a bit, giving it short feet with a

small cutout in the center. All of it is now just waiting on the

tailpiece, as the body block is complete - the last coat of varnish

is dry and polished.

The tailpiece inlay once again didn't work (the thin pieces kept popping out as soon as the wood was stressed. So I finally deceded to scrap the idea entirely, and carved a THIRD tailpiece, this time just carving the design into it rather than inlaying it. That done, the instrument parts were finished!

The

finished instrument. The strings are once again natural gut strings

from Daniel

Larson at Gamut Strings from where I get all my

strings. This shows the top/side/bottom, 3/4 view, and a closeup of

how the head finally turned out. Then comes that horrible moment when

you finally get to hear the thing once it's strung up and discover

whether you made a pretty sculpture or a musical instrument. In this

case I was rather surprised. I had expected the cedar soundboard to

make a slightly more warm tone than my personal instrument (the

highly carved one above). Instead, the instrument is actually

slightly brighter, and louder than mine. Now the body cavity is

slightly smaller, and the walls and back are considerably thinner

(the relief carving on mine is much deeper - this one weighs about

half of mine), and I did redesign the bridge, so it's difficult to

tell which of those factors is the actual culprit (or combination of

all of them). In any event, it actually sounds very nice.

The

finished instrument. The strings are once again natural gut strings

from Daniel

Larson at Gamut Strings from where I get all my

strings. This shows the top/side/bottom, 3/4 view, and a closeup of

how the head finally turned out. Then comes that horrible moment when

you finally get to hear the thing once it's strung up and discover

whether you made a pretty sculpture or a musical instrument. In this

case I was rather surprised. I had expected the cedar soundboard to

make a slightly more warm tone than my personal instrument (the

highly carved one above). Instead, the instrument is actually

slightly brighter, and louder than mine. Now the body cavity is

slightly smaller, and the walls and back are considerably thinner

(the relief carving on mine is much deeper - this one weighs about

half of mine), and I did redesign the bridge, so it's difficult to

tell which of those factors is the actual culprit (or combination of

all of them). In any event, it actually sounds very nice.

In

order to ship the instrument to its new home, it needed a case. In

brief searching, I was able to locate a 16" oblong viola

hardcase for surprisingly little money from the Sam Ash store near my

house. With the addition of a tailbit insert (made from a piece of

dense foam sewn into a covering of quilted cotton), it fits quite

nicely and snugly. It now is in the hands of its new owner!.

In

order to ship the instrument to its new home, it needed a case. In

brief searching, I was able to locate a 16" oblong viola

hardcase for surprisingly little money from the Sam Ash store near my

house. With the addition of a tailbit insert (made from a piece of

dense foam sewn into a covering of quilted cotton), it fits quite

nicely and snugly. It now is in the hands of its new owner!.

Since of course people ask "So what do these things sound like?" here's a (admittedly hasty) recording of this citole before I packed it up for shipping. The piece is Ce Fut en Mai, a 13th century French piece probably by Moniot d'Arras. Click on the sound title to hear it!

CITOLE NUMBER FIVE/SIX I decided to try to do a pair of instruments, for three reasons. First I wanted to try to copy the Parma Baptistry instrument, because it seems to be the most often copied of them. Second, I wanted to see if I could produce multiple instruments off the same pattern. And thirdly, one of the problems I've encountered with the instrument is the short string-length. The 13-14 inch scale with gut strings makes for a bright sounding higher pitched instrument. Trying to tune it as low as the low notes of a violin, for example, means that the low string is quite thick and a bit thuddy in sound. Strummed heavily with the other strings it works fine, but when plucking out individual notes, it doesn't "ring" as well as the higher pitched strings. The only way to make the string thinner would be to either raise the pitch more, or to lengthen the sounding distance (the bridge to nut length). This runs into the opposite problem on the high end of the instrument. The longer length means the string either has to be extremely thin, or have very little tension, both of which reduces the quality of the sound. Even still, I decided to try a longer sounding length, and the Parma model allows for that rather readily without making a bigger sounding box. The body size is about the same, but the bridge can me moved pretty far back on the body, making for a sounding length potentially as long as 16 inches (like a viola more than a violin). So this is that experiment. These instruments will have the parma body outline, be constructed of cherry wood, and have low bridges with inlaid fingerboards, so that the top surface of the instrument is perfectly flat, much like a renaissance lute.

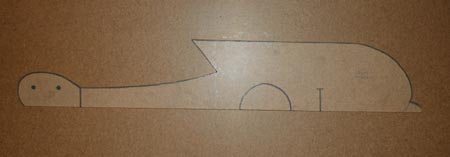

This

is the pattern. Most luthier patterns are the "half-instrument"

so that the instrument stays symmetrical down the long axis. I cut

this from a 1/8" thick piece of masonite. It shows the

approximate positions of the soundhole and bridge, though I will be

moving the bridge farther back on the instrument.

This

is the pattern. Most luthier patterns are the "half-instrument"

so that the instrument stays symmetrical down the long axis. I cut

this from a 1/8" thick piece of masonite. It shows the

approximate positions of the soundhole and bridge, though I will be

moving the bridge farther back on the instrument.

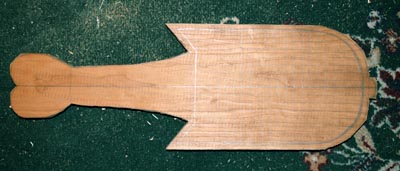

The

block of wood used was actually the remaining bit of the long block

used for the dog-headed citole above. That piece was originally eight

feet long, so plenty left over. The pattern was traced on both sides

of the wood, so that it could be more accurately cut out. This is the

basic instrument block cut out of the wood.

The

block of wood used was actually the remaining bit of the long block

used for the dog-headed citole above. That piece was originally eight

feet long, so plenty left over. The pattern was traced on both sides

of the wood, so that it could be more accurately cut out. This is the

basic instrument block cut out of the wood.

The

next bit of cutting. The end of the instrument has been rounded off a

bit, and the slotting where I need to chisel out the curve of the

neck has been done.

The

next bit of cutting. The end of the instrument has been rounded off a

bit, and the slotting where I need to chisel out the curve of the

neck has been done.

A

bit of amusement - I didn't actually notice Peebs sneaking into this

picture until I looked at them. One of my rabbits deciding to "help"

Daddy "carve" the instrument block (nom nom nom!).

A

bit of amusement - I didn't actually notice Peebs sneaking into this

picture until I looked at them. One of my rabbits deciding to "help"

Daddy "carve" the instrument block (nom nom nom!).

The

basic body block shape has been established. The neck has been carved

down with the chisels to the basic shape, and the peghead rounded

out. The back end of the body has also been more rounded off, and the

tailknub softened. With the instrument's outer line more or less

established, it's time to hollow out the body. A heavy penciled line

marks the space to be carved out, and I grid the space in 1/2 inch

blocks to drill out the holes to begin the hollowing process.

The

basic body block shape has been established. The neck has been carved

down with the chisels to the basic shape, and the peghead rounded

out. The back end of the body has also been more rounded off, and the

tailknub softened. With the instrument's outer line more or less

established, it's time to hollow out the body. A heavy penciled line

marks the space to be carved out, and I grid the space in 1/2 inch

blocks to drill out the holes to begin the hollowing process.

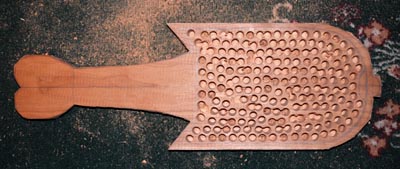

Using

a "stoppered" 1/2 inch drill bit, I fill the space to be

hollowed out with as many holes as I can fit. This dramatically

speeds up the hollowing process with the chisels. As this is the

softer cherry wood rather than the very hard maple, this only took an

evening to drill out. Thankfully there were no blow-throughs. The

body cavity of this instrument looks to be the largest of any of them

to date.

Using

a "stoppered" 1/2 inch drill bit, I fill the space to be

hollowed out with as many holes as I can fit. This dramatically

speeds up the hollowing process with the chisels. As this is the

softer cherry wood rather than the very hard maple, this only took an

evening to drill out. Thankfully there were no blow-throughs. The

body cavity of this instrument looks to be the largest of any of them

to date.

Next

I take the straight and scoop chisels and roughly hack out the

hollowed space. The sidewalls can be cut fairly smoothly with the

chisels, but the front and back ends of the body cavity where the

chisel has to cut cross-grain are best done with the dremel. I've

dulled too many chisels trying to hammer my way through them. You can

also see that the neck has just been rough chiseled at this point,

and the back curve is still segmented from the sawing.

Next

I take the straight and scoop chisels and roughly hack out the

hollowed space. The sidewalls can be cut fairly smoothly with the

chisels, but the front and back ends of the body cavity where the

chisel has to cut cross-grain are best done with the dremel. I've

dulled too many chisels trying to hammer my way through them. You can

also see that the neck has just been rough chiseled at this point,

and the back curve is still segmented from the sawing.

With

the space of the hollowing established, I turned to the neck and

peghead. They started off the full thickness of the wood (about two

inches), but need to be brought down to about 1/2-3/4 of an inch. The

first part was to just saw the whole thing in half, leaving a piece

about one inch thick. The peghead is then angled a bit downward, and

the neck thinned down. Here you can see the chisel work shaving down

the peghead and neck and angling the joint between the body and the

neck.

With

the space of the hollowing established, I turned to the neck and

peghead. They started off the full thickness of the wood (about two

inches), but need to be brought down to about 1/2-3/4 of an inch. The

first part was to just saw the whole thing in half, leaving a piece

about one inch thick. The peghead is then angled a bit downward, and

the neck thinned down. Here you can see the chisel work shaving down

the peghead and neck and angling the joint between the body and the

neck.

The

neck showing the thickness reduction.

The

neck showing the thickness reduction.

The

rough neck work finished. Here the neck has been evened out (both

sides mirrored accurately), and the sides and joint to body rounded

off with the dremel. The peghead has also been thinned and angled. In

this picture, the upper "wing" has been cleaned up but the

lower one still has some work to do.

The

rough neck work finished. Here the neck has been evened out (both

sides mirrored accurately), and the sides and joint to body rounded

off with the dremel. The peghead has also been thinned and angled. In

this picture, the upper "wing" has been cleaned up but the

lower one still has some work to do.

Cleaning

out the body cavity farther. The floor of the cavity has been leveled

out so that it is even across the space (except at the very back

where the back wall still needs to be cleaned up). The front wall has

been smoothed and cleaned up, and the upper wing here clean up. The

lower wing still needs final shaping and the "point" on the

inner space cleared out. I also have decided, after closer

examination of the original image, that the original instrument

didn't have a tail knub, but that the strings appear to either be

secured to pins or to a endpeg. Either way, I sliced off the tail

knub, and finished rounding off the back of the instrument.

Cleaning

out the body cavity farther. The floor of the cavity has been leveled

out so that it is even across the space (except at the very back

where the back wall still needs to be cleaned up). The front wall has

been smoothed and cleaned up, and the upper wing here clean up. The

lower wing still needs final shaping and the "point" on the

inner space cleared out. I also have decided, after closer

examination of the original image, that the original instrument

didn't have a tail knub, but that the strings appear to either be

secured to pins or to a endpeg. Either way, I sliced off the tail

knub, and finished rounding off the back of the instrument.

Putting

together the soundboard now. This is the design for the rosette. The

person who wanted this instrument was trying to get a lion design

into it. This presented two problems - historically, most rosettes

were geometrically designed, and it is extremely rare to non-existant

to see actual figurative designs outside of the deep multi-layered

baroque parchment roses. So I compromised, and came up with this

Celtic zoomorphic of a pair of intertwined lions. It still is mostly

geometric but presents the lions anyway. Obviously it would be

unlikely to see a Celtic design on an Italian instrument, but I'll

let that one slip this time.

Putting

together the soundboard now. This is the design for the rosette. The

person who wanted this instrument was trying to get a lion design

into it. This presented two problems - historically, most rosettes

were geometrically designed, and it is extremely rare to non-existant

to see actual figurative designs outside of the deep multi-layered

baroque parchment roses. So I compromised, and came up with this

Celtic zoomorphic of a pair of intertwined lions. It still is mostly

geometric but presents the lions anyway. Obviously it would be

unlikely to see a Celtic design on an Italian instrument, but I'll

let that one slip this time.

This

is the soundboard cut from its sheet. It is western red cedar, and

like with the carpathian spruce, there is a large differential in the

hardness between the winter and summer growth rings, so it is very

strong along the grain, but flexible perpendicular to it. This is

after it has been thinned down (using the planes) and sanded smooth

to start the rosette.

This

is the soundboard cut from its sheet. It is western red cedar, and

like with the carpathian spruce, there is a large differential in the

hardness between the winter and summer growth rings, so it is very

strong along the grain, but flexible perpendicular to it. This is

after it has been thinned down (using the planes) and sanded smooth

to start the rosette.

Carving

the rosette into the soundboard. I initially had thought this would