- •The citole project

- •Warning: This page is horrifically graphically intensive (about 200 images at the moment). It will take a long time to load everything.

- •In Adam Davie's "Life of Alexander" from the 14th century, we read "At the feste was trumping,/ Piping and eke taborying,/ Sytolyng and eke harpyng."

- •I have a mini-lathe that I then used to turn the blocks to cut two pegs out of each one. Top here is the rough block, below is the block after being through the lathe.

- •I was happy with how it came out, and worked out the problems that I wanted to.

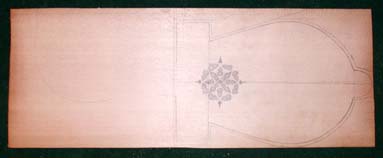

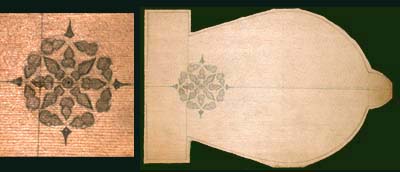

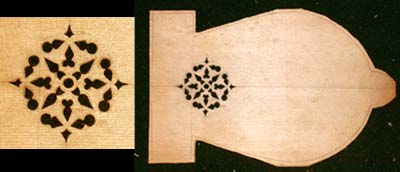

- •In the interim, working on the soundboard, since carving out the rosette takes a bit of time. This is the design for the rosette.

- •It will also have a carved pegbox with an animal head, only this time the animal will be a lion, based roughly on Celtic designs.

- •Vincenzo cipriani in Italy does another version of the cantiga style citole. See his website for more views of the instruments - very cute animal heads! No prices anywhere that I can find.

I have a mini-lathe that I then used to turn the blocks to cut two pegs out of each one. Top here is the rough block, below is the block after being through the lathe.

The

turned block then is cut into two pegs that look like the right one

in this image. That is then carved down into the oakleaf shape that

will be the final pegs (left) and the peg stem run through the violin

pegshaver to taper it appropriately. I had debated inlaying the lines

of the leaf in ebony, but after a small test decided that if done

correctly, they look just drawn on. And I think the 3-D effect of the

carved lines better matched the rest of the instrument. My wife

agreed.

The

turned block then is cut into two pegs that look like the right one

in this image. That is then carved down into the oakleaf shape that

will be the final pegs (left) and the peg stem run through the violin

pegshaver to taper it appropriately. I had debated inlaying the lines

of the leaf in ebony, but after a small test decided that if done

correctly, they look just drawn on. And I think the 3-D effect of the

carved lines better matched the rest of the instrument. My wife

agreed.

Here

are the four complete pegs in place. I had deepened the depression in

the top to allow for the strings to turn down to hold the nut in

place. The roughed out nut is also visible here.

Here

are the four complete pegs in place. I had deepened the depression in

the top to allow for the strings to turn down to hold the nut in

place. The roughed out nut is also visible here.

Finishing

up the body. The fingerboard is finished with rubbed oil (several

coats). The body is then coated with an oil varnish, applied with a

small brush. The large number of nooks and crannies mean that each

coat took about two and a half hours, and then that has to dry for at

least 24 hours before the next coat can be applied, etc. Three coats

were applied this way, with light sanding and burnishing inbetween

each coat. The wood did not really tiger stripe, but the curling and

swirls in the grain did come out nicely. The maple turned a nice

golden color. The spruce however took several tries to get an even

coat, and even so it darkened in a slightly uneven pattern. Not sure

why. Doesn't look bad, just unexpected, as the sitka spruce I've used

in the past didn't acquire that kind of mottling.

Finishing

up the body. The fingerboard is finished with rubbed oil (several

coats). The body is then coated with an oil varnish, applied with a

small brush. The large number of nooks and crannies mean that each

coat took about two and a half hours, and then that has to dry for at

least 24 hours before the next coat can be applied, etc. Three coats

were applied this way, with light sanding and burnishing inbetween

each coat. The wood did not really tiger stripe, but the curling and

swirls in the grain did come out nicely. The maple turned a nice

golden color. The spruce however took several tries to get an even

coat, and even so it darkened in a slightly uneven pattern. Not sure

why. Doesn't look bad, just unexpected, as the sitka spruce I've used

in the past didn't acquire that kind of mottling.

Setting

the height for the bridge and nut. Both pieces are intially cut WAY

too high, and then I file a notch into them and continually lower the

notch until the action (height of the strings above the fretboard) is

about where I want it. I use a piece of black nylon string as a

mock-up for the gut strings (rather than wasting the rather expensive

strings on such a set-up). Once the notches are set where I want

them, I carve down the nut and bridge to a level with the notch, and

add the remaining notches for the other strings at their appropriate

spacing. The nut and bridge are then given a light coating of oil to

seal them. With the gaboon ebony, this turns the dark brown wood a

serious jet black! Neither is glued into place - both are held in

place by the tension of the strings.

Setting

the height for the bridge and nut. Both pieces are intially cut WAY

too high, and then I file a notch into them and continually lower the

notch until the action (height of the strings above the fretboard) is

about where I want it. I use a piece of black nylon string as a

mock-up for the gut strings (rather than wasting the rather expensive

strings on such a set-up). Once the notches are set where I want

them, I carve down the nut and bridge to a level with the notch, and

add the remaining notches for the other strings at their appropriate

spacing. The nut and bridge are then given a light coating of oil to

seal them. With the gaboon ebony, this turns the dark brown wood a

serious jet black! Neither is glued into place - both are held in

place by the tension of the strings.

All

the pieces are now down and ready for assembly with the strings. The

four pegs need still to be drilled, which was done with the little

finger drills. Otherwise it is ready for final set-up.

All

the pieces are now down and ready for assembly with the strings. The

four pegs need still to be drilled, which was done with the little

finger drills. Otherwise it is ready for final set-up.

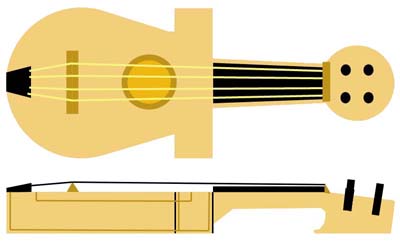

The

completed instrument. The first image shows back, side and top, the

second image a perspective view. Overall I think it came out very

nicely, and the tone is brighter and stronger than on the other ones,

probably because of the maple versus the cherry wood (harder usually

equates to brighter). Strings are made of natural gut, acquired from

Gamut

Strings, run by Dan Larsen. I've used his strings

almost exclusively for my vielles and harp, and they have worked

really well to this point. The instrument is presently tuned G d g

d', with the lowest two strings the same notes as the lowest strings

of a violin. String diameters are (in mm) .52, .74, 1.04, and 1.50

for those that care about such things. The tail gut is some leftover

1.54 string I had from stringing the bray harp. As soon as I've had a

chance to practice it a bit and get it to sound good, I will put up a

recording of what the instrument sounds like.

The

completed instrument. The first image shows back, side and top, the

second image a perspective view. Overall I think it came out very

nicely, and the tone is brighter and stronger than on the other ones,

probably because of the maple versus the cherry wood (harder usually

equates to brighter). Strings are made of natural gut, acquired from

Gamut

Strings, run by Dan Larsen. I've used his strings

almost exclusively for my vielles and harp, and they have worked

really well to this point. The instrument is presently tuned G d g

d', with the lowest two strings the same notes as the lowest strings

of a violin. String diameters are (in mm) .52, .74, 1.04, and 1.50

for those that care about such things. The tail gut is some leftover

1.54 string I had from stringing the bray harp. As soon as I've had a

chance to practice it a bit and get it to sound good, I will put up a

recording of what the instrument sounds like.

I

ordered a custom hardcase from Kingham

MTM Cases in England, which makes very nice cases for

early instruments. Got a little whacked on the exchange rate (dollar

sucks at the moment to the pound), but otherwise a very nice case.

Wooden base body, covered in leather, lined with padding and crushed

green velvet. You provide schematics to Kingham, and they build the

case to match. Took about eight weeks to arrive, but came out quite

excellently.

I

ordered a custom hardcase from Kingham

MTM Cases in England, which makes very nice cases for

early instruments. Got a little whacked on the exchange rate (dollar

sucks at the moment to the pound), but otherwise a very nice case.

Wooden base body, covered in leather, lined with padding and crushed

green velvet. You provide schematics to Kingham, and they build the

case to match. Took about eight weeks to arrive, but came out quite

excellently.

In the interim (while working on the carving of the body of Citole One) I have been having a little difficulty thinking out abstractly how I want to attach the fingerboard, how I want to do the edge binding, and such problems. So, when a friend really really wanted a citole, I decided to make one as a full-sized model to work out these issues before irrevocably damaging the body I'd spent so many hours on, esp. with all the carving. Dubbed "Citole 2" for the moment, this was going to be a much simpler instrument, with simpler lines, and practically no decoration other an a carved out central rose and some edge binding. I had a large block of cherry that was the backup piece to the eastern maple, so I decided to use that for this instrument.

Top

is the set of drawings for this version. Next is the block with the

pattern drawn on. Third shows the body rough cut - I did this using a

scroll orbital saw I have - the cherry is much softer than the maple,

and I can use the power tools readily on it. The fourth shows the

more cleaned up body and its more or less final outline. The fifth

image shows where I did the standard drilling out of all the holes to

simplify the hollowing of the body block.

Top

is the set of drawings for this version. Next is the block with the

pattern drawn on. Third shows the body rough cut - I did this using a

scroll orbital saw I have - the cherry is much softer than the maple,

and I can use the power tools readily on it. The fourth shows the

more cleaned up body and its more or less final outline. The fifth

image shows where I did the standard drilling out of all the holes to

simplify the hollowing of the body block.

This

is followed by using a full sized router to hollow out the body and

the peg-head, which took only a couple of hours one afternoon, and

then I used the saw and chisels above to rough out the neck. It is

truly amazing the difference in the ease of working with the softer

cherry - the wood removal is very quick and simple. And the block

already weighs half what the maple does, even though it has a lot

more wood in it - the difference in density is VERY obvious here. It

also resonates really loudly, especially with the hammered chisels.

The third picture is the floor of the body thinned down to

appropriate thickness using the mid-sized chisels above. Still has to

be finally smoothed out, but is getting there.

This

is followed by using a full sized router to hollow out the body and

the peg-head, which took only a couple of hours one afternoon, and

then I used the saw and chisels above to rough out the neck. It is

truly amazing the difference in the ease of working with the softer

cherry - the wood removal is very quick and simple. And the block

already weighs half what the maple does, even though it has a lot

more wood in it - the difference in density is VERY obvious here. It

also resonates really loudly, especially with the hammered chisels.

The third picture is the floor of the body thinned down to

appropriate thickness using the mid-sized chisels above. Still has to

be finally smoothed out, but is getting there.

Here

you see the body block more or less completed (little bit of cleaning

up on the inside to do, but the shaping is done). The neck has been

thinned down and rounded off. The pegbox has been rounded off

cleanly, the hollowing smoothed out and cleaned up, and the little

backward hook carved out. The heel (where the neck meets the body)

has been shaped, and seems sturdy enough to hold the string pressure,

though I'll probably change the joining point to a crisper line

rather than soft slope it is now. And the little tail stub has been

cleaned up and rounded off smoothly. Obviously the final sanding pass

hasn't been done, but that will be done once the soundboard and

fingerboard are on. Mostly this was all done with files, and some

dremel work, especially to shape the hook. There a little more clean

up off the primary cavity (to thin the walls and floor down a little

more), but next is the soundboard, tail and fingerboard.

Here

you see the body block more or less completed (little bit of cleaning

up on the inside to do, but the shaping is done). The neck has been

thinned down and rounded off. The pegbox has been rounded off

cleanly, the hollowing smoothed out and cleaned up, and the little

backward hook carved out. The heel (where the neck meets the body)

has been shaped, and seems sturdy enough to hold the string pressure,

though I'll probably change the joining point to a crisper line

rather than soft slope it is now. And the little tail stub has been

cleaned up and rounded off smoothly. Obviously the final sanding pass

hasn't been done, but that will be done once the soundboard and

fingerboard are on. Mostly this was all done with files, and some

dremel work, especially to shape the hook. There a little more clean

up off the primary cavity (to thin the walls and floor down a little

more), but next is the soundboard, tail and fingerboard.

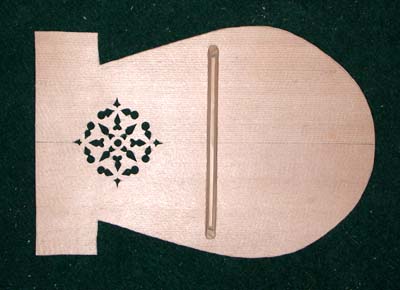

Here

is the soundboard, made from a sitka spruce board (1/2 of a jumbo

guitar soundboard piece about 8" wide). First image shows

penciling out the piece (tracing the shape off the actual body). Next

I rough-cut the soundboard out of the wood with a coping saw. After

this, I drilled out the holes of the rosette, and then filed them

into shape with the mini and micro files. Last image shows the board

with the finished rosette. There were gouges on one side where the

drill had chopped rather than sliced into the soft spruce, so that

will become the underside. The top then took a number of passes

through my handheld belt-sander to thin it down to about 1/8 inch or

so thick.

Here

is the soundboard, made from a sitka spruce board (1/2 of a jumbo

guitar soundboard piece about 8" wide). First image shows

penciling out the piece (tracing the shape off the actual body). Next

I rough-cut the soundboard out of the wood with a coping saw. After

this, I drilled out the holes of the rosette, and then filed them

into shape with the mini and micro files. Last image shows the board

with the finished rosette. There were gouges on one side where the

drill had chopped rather than sliced into the soft spruce, so that

will become the underside. The top then took a number of passes

through my handheld belt-sander to thin it down to about 1/8 inch or

so thick.

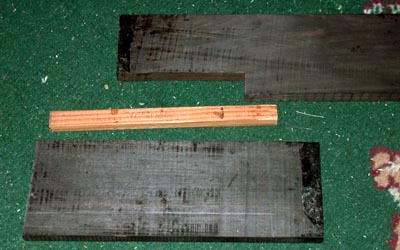

Still

on citole number two. These are the chunks of wood that are making

the other parts of the citole. On top is a piece of scrap ebony that

the tailpiece, nut and bridge will be cut out of. Next is the piece

of red cedar that will be used (already cut to length before this

picture) as the support brace for the soundboard (at its widest

point, more or less). On bottom is the piece of ebony that will be

cut into the fingerboard. The globby stuff on it is sealing wax to

keep the ebony from absorbing moisture, which it tends to do in long

storage. The second picture shows the finished brace, roughly a soft

upside-down T in cross-section, with tapering ends. This was carved

with knives, and evened out with the long file.

Still

on citole number two. These are the chunks of wood that are making

the other parts of the citole. On top is a piece of scrap ebony that

the tailpiece, nut and bridge will be cut out of. Next is the piece

of red cedar that will be used (already cut to length before this

picture) as the support brace for the soundboard (at its widest

point, more or less). On bottom is the piece of ebony that will be

cut into the fingerboard. The globby stuff on it is sealing wax to

keep the ebony from absorbing moisture, which it tends to do in long

storage. The second picture shows the finished brace, roughly a soft

upside-down T in cross-section, with tapering ends. This was carved

with knives, and evened out with the long file.

Yet

more citole number two. The finished back-brace has been glued onto

the soundboard. It is just a tiny bit narrower than the body cavity,

though I initially centered it off a little, and had to correct that

with files after it had been glued. The edges of the soundboard are

cleaned up a bit more with dremel and files, and then it is attached

to the body of the citole. As in the past, I've found that

hand-weights work very well as clamps for this purpose... this is my

kitchen table. The glue is luthier glue I acquired from LMII.

Yet

more citole number two. The finished back-brace has been glued onto

the soundboard. It is just a tiny bit narrower than the body cavity,

though I initially centered it off a little, and had to correct that

with files after it had been glued. The edges of the soundboard are

cleaned up a bit more with dremel and files, and then it is attached

to the body of the citole. As in the past, I've found that

hand-weights work very well as clamps for this purpose... this is my

kitchen table. The glue is luthier glue I acquired from LMII.

This

is the tailpiece of citole number two. It has been cut out of a bit

of the ebony with the coping saw, and shaped with files and the

little chisels. It will fit over the tail nubby of the body. The

string holes hadn't been added when I took this picture (see below).

This

is the tailpiece of citole number two. It has been cut out of a bit

of the ebony with the coping saw, and shaped with files and the

little chisels. It will fit over the tail nubby of the body. The

string holes hadn't been added when I took this picture (see below).

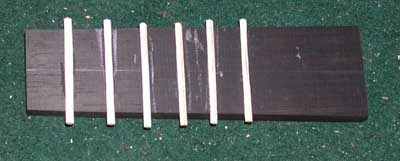

This

is the fingerboard construction for citole number two. First, I cut

out the fingerboard from a chunk of the ebony with the coping saw,

then leveled it and straightened the edges with the belt-sander.

There will only be six frets (short fingerboard only played in first

position, as generally was true for medieval instruments). The

functional string length will be 13.25 inches, and I used a fret

calculator to set the spacing. The frets were carved

from holly wood, originally from 1x1 inch block down to 1/8 inch by

1/8 inch, starting with coping saw and ending up with carving knives

and files. The slots on the ebony were first cut with an Exacto mitre

saw, then broadened to a wide V with the medium files. The last image

shows the frets glued onto the fingerboard. Each had to be separately

glued and clamped, which I did with the 15 lb. handweight. The shiny

bits are some excess glue that got wiped onto the board - it was

removed (eventually) with an Exacto knife and a little file work.

This

is the fingerboard construction for citole number two. First, I cut

out the fingerboard from a chunk of the ebony with the coping saw,

then leveled it and straightened the edges with the belt-sander.

There will only be six frets (short fingerboard only played in first

position, as generally was true for medieval instruments). The

functional string length will be 13.25 inches, and I used a fret

calculator to set the spacing. The frets were carved

from holly wood, originally from 1x1 inch block down to 1/8 inch by

1/8 inch, starting with coping saw and ending up with carving knives

and files. The slots on the ebony were first cut with an Exacto mitre

saw, then broadened to a wide V with the medium files. The last image

shows the frets glued onto the fingerboard. Each had to be separately

glued and clamped, which I did with the 15 lb. handweight. The shiny

bits are some excess glue that got wiped onto the board - it was

removed (eventually) with an Exacto knife and a little file work.

Citole

Number Two as it stands to this point. The soundboard is now

attached, and I've clean up the edges so that they are flush with the

body, done mostly with files. I also cleaned up the neck joint a

little more, and the tail joint a little more. At this point I

brought it and the fingerboard to its soon-to-be owner, to make sure

that she could get her fingers around the neck (she has rather small

hands). After testing, I decided I needed to thin the fingerboard

some more, and thin the neck just a little bit. The neck was thinned

(top to bottom) with the heavy file a little bit; the fingerboard was

thinned (top to bottom, or thickness)down to about 1/4 an inch with

the belt-sander.

Citole

Number Two as it stands to this point. The soundboard is now

attached, and I've clean up the edges so that they are flush with the

body, done mostly with files. I also cleaned up the neck joint a

little more, and the tail joint a little more. At this point I

brought it and the fingerboard to its soon-to-be owner, to make sure

that she could get her fingers around the neck (she has rather small

hands). After testing, I decided I needed to thin the fingerboard

some more, and thin the neck just a little bit. The neck was thinned

(top to bottom) with the heavy file a little bit; the fingerboard was

thinned (top to bottom, or thickness)down to about 1/4 an inch with

the belt-sander.

Citole

Number Two - attaching the fingerboard. First, I cut off the frets

flush with the fingerboard (so they didn't stick out too far), and

lined up the fingerboard with the centerlines drawn on the body. The

fingerboard was clamped (I used folded bristol board to cushion

against the marks of the clamps on the wood of the neck and

fingerboard/frets). When that was dry, I refinished the edges of the

neck and fingerboard so they were flush, and bevel-edged the frets.

Citole

Number Two - attaching the fingerboard. First, I cut off the frets

flush with the fingerboard (so they didn't stick out too far), and

lined up the fingerboard with the centerlines drawn on the body. The

fingerboard was clamped (I used folded bristol board to cushion

against the marks of the clamps on the wood of the neck and

fingerboard/frets). When that was dry, I refinished the edges of the

neck and fingerboard so they were flush, and bevel-edged the frets.

Citole

Number Two - attaching the tailpiece. The angle of the tailpiece

proved a challenge to clamp - I tried bracing it with the bristol

board, but that didn't work. In the end, I just used the tried &

true 15 lb. handweight to clamp it. Seemed to work fine. You can see

the string-holes in the tailpiece now, spaced about 1/4" apart.

Like with the fingerboard, when that was dry, I refinished the tail

stub so that all the sides were flush with the tailpiece, and the

joint-point of the tail to the body was edged rather than

soft-blended.

Citole

Number Two - attaching the tailpiece. The angle of the tailpiece

proved a challenge to clamp - I tried bracing it with the bristol

board, but that didn't work. In the end, I just used the tried &

true 15 lb. handweight to clamp it. Seemed to work fine. You can see

the string-holes in the tailpiece now, spaced about 1/4" apart.

Like with the fingerboard, when that was dry, I refinished the tail

stub so that all the sides were flush with the tailpiece, and the

joint-point of the tail to the body was edged rather than

soft-blended.

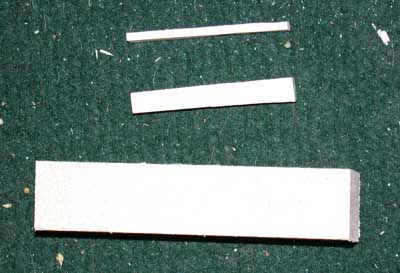

Citole

Number Two - small bits. Here are shown the little pieces of ebony

that will become the end nut (the piece at the end of the fingerboard

that the strings sit in), and the bridge. Obviously they haven't been

finished yet at this point. The other picture shows what is happening

with the pegs. I don't have a lathe, so turning the pegs is difficult

(I have used a drill in the past, but it is rather awkward). So

instead of scratch making them, I got a set of four ebony violin pegs

from a music shop, and have decided to reshape them into more

appropriate medieval shape. I cut out notches of the corners with a

coping saw, and then used the dremel to flatten the surface of the

peg, and then used the files to shape it into a kind of tapered club.

This picture shows the starting and finishing points. The pegs

finally with oiled with artist quality linseed oil.

Citole

Number Two - small bits. Here are shown the little pieces of ebony

that will become the end nut (the piece at the end of the fingerboard

that the strings sit in), and the bridge. Obviously they haven't been

finished yet at this point. The other picture shows what is happening

with the pegs. I don't have a lathe, so turning the pegs is difficult

(I have used a drill in the past, but it is rather awkward). So

instead of scratch making them, I got a set of four ebony violin pegs

from a music shop, and have decided to reshape them into more

appropriate medieval shape. I cut out notches of the corners with a

coping saw, and then used the dremel to flatten the surface of the

peg, and then used the files to shape it into a kind of tapered club.

This picture shows the starting and finishing points. The pegs

finally with oiled with artist quality linseed oil.

Citole

Number Two - the edge binding. Here was one of the bigger logistical

problems - how to cut the ledge for the edge-binding? I had acquired

some nice ebony binding strips from LMII,

about 1/4 inch tall, 1/16 inch thick. My first thought was to try to

use the dremel router to route out the space, but tests proved to be

difficult to control. Rigging up the dremel base to try to control

the depth proved impossible to maintain around the curves, and was

entirely impossible to reach into the acute corners (I tested on

scrap wood). So, instead I resorted to what I did in the test above -

I used the mini-chisels to actually carve it out. I wedged a line

around the instrument, and then chipped off the wood down to that

line, and filed it smooth. It isn't extremely efficient (took about

four hours to get all the way around the instrument), but it was

controlled, and seemed to work. Next the edge binding is glued on.

Citole

Number Two - the edge binding. Here was one of the bigger logistical

problems - how to cut the ledge for the edge-binding? I had acquired

some nice ebony binding strips from LMII,

about 1/4 inch tall, 1/16 inch thick. My first thought was to try to

use the dremel router to route out the space, but tests proved to be

difficult to control. Rigging up the dremel base to try to control

the depth proved impossible to maintain around the curves, and was

entirely impossible to reach into the acute corners (I tested on

scrap wood). So, instead I resorted to what I did in the test above -

I used the mini-chisels to actually carve it out. I wedged a line

around the instrument, and then chipped off the wood down to that

line, and filed it smooth. It isn't extremely efficient (took about

four hours to get all the way around the instrument), but it was

controlled, and seemed to work. Next the edge binding is glued on.

Okay, I had a slight problem with the camera, so we lost the intermediate photos, and only have the photos of the finished instrument of Citole Number Two. I'll try to go through the final stages as best I might.

These

images show the edge binding fairly cleanly as it ended up. The edge

binding was made up of thin strips about 30" long of ebony. I

cut very exacting lengths for each of the straight sections around

the "wings" of the citole and beveled the meeting points so

that they met flush on the corners. The curved sides of the

instrument each had one long piece that was bent into shape by

soaking the piece in warm water, and then steaming it (over a

teakettle) and finally taping the softened strip to the body to mold

it. When it dried it held the shape pretty well, and didn't crack.

The binding was glued to the ridges, held in place by tape. When that

had dried overnight, using sandpaper and my "Mouse" powered

handsander, I sanded the binding flush to the sides and to the top of

the body. Then the hold body was sanded down, corners rounded a

little softer, and the top and bottom plates sanded smooth.

These

images show the edge binding fairly cleanly as it ended up. The edge

binding was made up of thin strips about 30" long of ebony. I

cut very exacting lengths for each of the straight sections around

the "wings" of the citole and beveled the meeting points so

that they met flush on the corners. The curved sides of the

instrument each had one long piece that was bent into shape by

soaking the piece in warm water, and then steaming it (over a

teakettle) and finally taping the softened strip to the body to mold

it. When it dried it held the shape pretty well, and didn't crack.

The binding was glued to the ridges, held in place by tape. When that

had dried overnight, using sandpaper and my "Mouse" powered

handsander, I sanded the binding flush to the sides and to the top of

the body. Then the hold body was sanded down, corners rounded a

little softer, and the top and bottom plates sanded smooth.

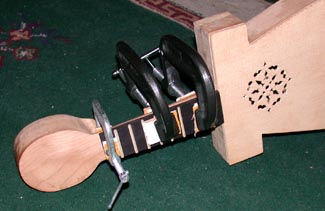

The

last actual bit of carving was the peghead. I spaced the four holes

for the pegs by making little paper circles that were slightly larger

in diameter than the pegs were wide, and making sure there was

clearance space for the pegs to turn completely and still have some

space between them. Then a pilot hole was drilled with a powered hand

drill slightly smaller than the narrowest end of the tapered peg. I

have a violin peg hole reamer, so that was used then to ream the hole

to the appropriate taper of the violin pegs. I also have a violin peg

shaver (I've played violin a long time) and used that to make sure

the pegs were of the same appropriate taper. The pegs, once fitted

basically to the holes, were way too long, so I cut the excess ends

off, and sanded and re-oiled the pegs. The next part was a new

experiment. The strings had to pass over the endnut, and then somehow

to the pegs on the other side of the peg-head. I had seen several

historical re-creations use the methods of pass-through holes, so I

wanted to see if they indeed were practical. For the gut strings I

think they work pretty well (though I think wire strings would carve

into the wood too badly - they would have had to have been braced

with ebony or other really hard wood). So there are two rectangular

holes that are just beyond the nut, cutting diagonally forward into

the underside of the peghead, so that the strings can then be

attached to the pegs there. The holes were first drilled, and then

shaped using the mini- and micro-files. The peghead was then sanded

and smoothed down.

The

last actual bit of carving was the peghead. I spaced the four holes

for the pegs by making little paper circles that were slightly larger

in diameter than the pegs were wide, and making sure there was

clearance space for the pegs to turn completely and still have some

space between them. Then a pilot hole was drilled with a powered hand

drill slightly smaller than the narrowest end of the tapered peg. I

have a violin peg hole reamer, so that was used then to ream the hole

to the appropriate taper of the violin pegs. I also have a violin peg

shaver (I've played violin a long time) and used that to make sure

the pegs were of the same appropriate taper. The pegs, once fitted

basically to the holes, were way too long, so I cut the excess ends

off, and sanded and re-oiled the pegs. The next part was a new

experiment. The strings had to pass over the endnut, and then somehow

to the pegs on the other side of the peg-head. I had seen several

historical re-creations use the methods of pass-through holes, so I

wanted to see if they indeed were practical. For the gut strings I

think they work pretty well (though I think wire strings would carve

into the wood too badly - they would have had to have been braced

with ebony or other really hard wood). So there are two rectangular

holes that are just beyond the nut, cutting diagonally forward into

the underside of the peghead, so that the strings can then be

attached to the pegs there. The holes were first drilled, and then

shaped using the mini- and micro-files. The peghead was then sanded

and smoothed down.

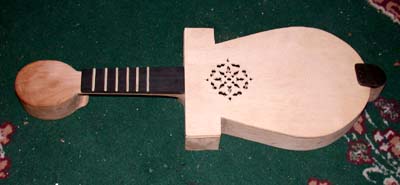

This

is the completed instrument, from top, side, bottom and angled views.

After final sanding, the body, neck, and peghead were lacquered using

a polymer lacquer, given about three/four coats. The cherry wood

darkened slightly to a dull reddish color (I used no dyes), and the

spruce to a pale golden yellow. The ebony of course ended up nearly

black. I lacquered the tailpiece, but the endnut, bridge and

fingerboard are only oiled with artist linseed oil (I just started

doing oil painting, so I have it around the house now). The bridge is

a floating bridge (meaning it's only held in place by the tension of

the strings, not glued to the soundboard), as is the nut. The

instrument was strung with natural gut strings acquired from Gamut

Strings, where I get my vielle strings, and have been

very satisfied with them. They are a little longer than violin

strings (sounding length about the same, but the tail is set farther

back). I filed the notches in the bridge and endnut with the

microfiles, and strung her up. The end result was quite nice - it has

more volume than I was expecting, a little louder than a lute. It is

tuned Gdgd' (the first two strings same as a violin, the upper two

one note lower than a violin), to make a nice open chord strum.

Presently it is with its happy new owner Wendy Gash, who is slowly

trying to learn it!

This

is the completed instrument, from top, side, bottom and angled views.

After final sanding, the body, neck, and peghead were lacquered using

a polymer lacquer, given about three/four coats. The cherry wood

darkened slightly to a dull reddish color (I used no dyes), and the

spruce to a pale golden yellow. The ebony of course ended up nearly

black. I lacquered the tailpiece, but the endnut, bridge and

fingerboard are only oiled with artist linseed oil (I just started

doing oil painting, so I have it around the house now). The bridge is

a floating bridge (meaning it's only held in place by the tension of

the strings, not glued to the soundboard), as is the nut. The

instrument was strung with natural gut strings acquired from Gamut

Strings, where I get my vielle strings, and have been

very satisfied with them. They are a little longer than violin

strings (sounding length about the same, but the tail is set farther

back). I filed the notches in the bridge and endnut with the

microfiles, and strung her up. The end result was quite nice - it has

more volume than I was expecting, a little louder than a lute. It is

tuned Gdgd' (the first two strings same as a violin, the upper two

one note lower than a violin), to make a nice open chord strum.

Presently it is with its happy new owner Wendy Gash, who is slowly

trying to learn it!