CHAPTER 3

SUUPLY, DEMAND & MARKET PRICE

Overview

As you read this chapter, look for answers to the following questions:

• What roles do prices play in a market economy?

• What affects the demand for goods and services in a market economy?

• What affects the supply of a particular good or service?

• How do price, demand, and supply interact?

• How do shifts in demand and supply affect prices?

Do you ever buy CDs or tapes? How about T-shirts and jeans? If so, you have participated in markets for recorded music and clothing. To an economist, a market consists of all the people interested in buying or selling a particular good or service. You become part of the CD market as you shop in a music store. You also enter a market when you sell goods or services. If you are looking for work in a fast-food restaurant or clothing store, you are part of the labor market.

The interaction of buyers and sellers in markets drives a market economy. Prices, as you have learned, also play an important role in the U.S. market system. But why are prices so important in a market economy? And how are they determined?

3.1. Prices In a Market Economy

Have you ever attended an auction, or seen one on TV? An auction shows the rationing effect of prices. The person conducting the sale—the auctioneer— offers individual items for sale. Buyers "enter the market" by signaling their willingness to pay a particular price. For example, many sports fans would happily pay $5 for an autographed pair of the shoes Michael Jordan wore during the 1992 Olympic Games. However, as the price rises to thousands of dollars, the number of interested buyers would probably fall off dramatically. In this case, price has rationed, or allocated, the shoes to a wealthy or fanatical basketball fan.

Although you don't usually think of the stores where you shop as "auctions," the economic principles are similar. At high prices there are usually fewer buyers. People buy more hamburger than steak, and a music store will sell more CDs at $16.95 than at $24.95. Relatively few people who enjoy football can afford to pay for the tickets, airfare, meals and hotel room required for a trip to the Super Bowl. Prices, as you can see, often determine who eats steak, buys CDs, and attends the Super Bowl.

Price increases and decreases also send messages to suppliers of goods and services. Prices encourage producers to increase or decrease their output. As prices rise, the increase attracts additional producers. Similarly, price decreases drive producers out of the market. For example, if farmers discovered that consumers were willing to pay higher prices for broccoli, you could expect many of them to plant broccoli instead of carrots. On the other hand, declining prices for Bart Simpson T-shirts signal producers to print fewer Simpson shirts. Economists call this the production-motivating function of prices.

But what causes prices to rise and fall in a market economy?

3.2. Demand

As winter ends, many clothing stores find that their inventories (stock of goods) of winter clothes are too large. How can they encourage people to buy winter items in March? Run a sale? That would be a good suggestion, because people will buy winter clothing in the spring if the price is low enough.

The Law of Demand. Demand is a consumer's willingness and ability to buy a product or service at a particular time and place. If you would like a new pair of athletic shoes but can't afford them, economists would describe your feeling as desire, not demand. But if you had the money and were ready to buy shoes, you would be included in their calculations.

The law of demand formally describes the rationing effect of prices. It says that other things being equal, more items will be bought at a lower price than at a higher price.

Suppose that your two friends, Lauren and Ralph, noticed that everyone, from babies to grandparents, wears T-shirts with colorful designs, the name of their school, favorite team, jokes—just about anything. They decided to start a T-shirt business and sell shirts with their school name and mascot. They also would design and sell shirts for special school events—homecoming, graduation.

Before they invested in T-shirts, silk-screening equipment, and the other supplies they would need, Lauren and Ralph conducted a survey to see if students would be interested in their shirts. Each student was asked the following question: "Would you spend $5.00 for a special homecoming T-shirt?" They repeated this question with different prices up to $20.00.

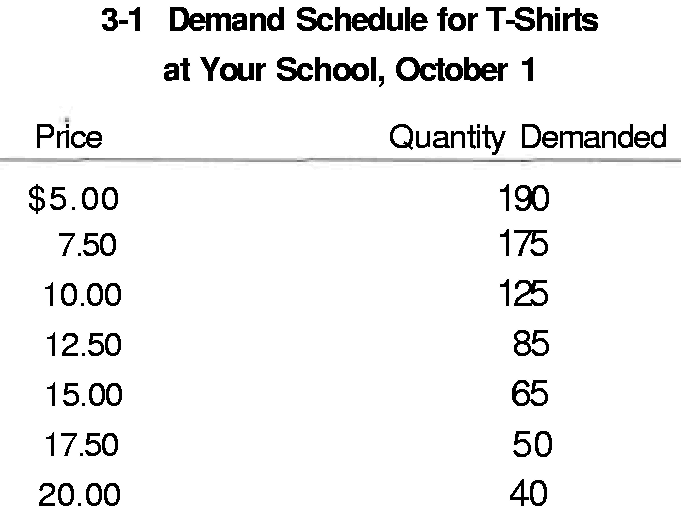

The Demand Schedule. The results of the survey were compiled in a demand schedule, Table 3-1, showing the quantities of a product that would be purchased at various prices at a given time.

The survey results illustrate the law of demand in action. According to the demand schedule, the number of shirts that students were ready, willing, and able to buy was greater at lower prices than at higher prices. This seems to be common sense. More people are willing to buy T-shirts, and anything else, at lower prices. And fewer people are willing to buy things at higher prices.

Price has a major effect on the quantity of any good or service consumers will demand. The availability of substitutes, and the economic principle of diminishing marginal utility further explain the relationship between price and quantity demanded.

• Substitutes. In many instances you can substitute one product for another. Some stores, for example, sell frozen yogurt as well as ice cream. Many ice cream lovers would buy frozen yogurt if the price of ice cream increased. Similarly, one's decision to have hamburger, steak, or fish often depends on the price of those substitutes. Economists describe this as the substitution effect of price changes on quantity demanded.

• Diminishing marginal utility. You might love pizza, but there is a limit to the amount you will eat at one time. Sooner or later, you'll reach a point where enjoyment decreases with every bite, no matter how low the cost. What is true of pizza applies to most everything. Even Calvin got enough of his "chocolate frosted sugar bombs." Economists call this diminishing marginal utility. Utility refers to the usefulness of something. Thus diminishing marginal utility is economists' way of describing the point reached when the next item consumed is less satisfying than the one before.

Diminishing marginal utility helps to explain why lower prices are needed to increase the quantity demanded. Since your desire for a second slice of pizza is probably less than it was for the first, you are not likely to buy more than one, except at a lower price. In most cases, you will choose to use your limited resources on something other than pizza to maximize the utility you receive from the money (get the most out of your money) you have to spend on a second slice of pizza.

A demand curve is a graph of the demand schedule. The curve in Figure 3-2 shows the relationship between the price of T-shirts and the quantity buyers were willing to purchase for homecoming. It lets Lauren and Ralph estimate what the demand would be for prices falling between the ones they surveyed. Although students were not questioned about how many shirts they would buy at $16.00, the curve lets them estimate the number would be about 55.