Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

accompanied by dysuria and tenesmus.

Bacterial cystitis may also cause urinary urgency; hematuria; fatigue; suprapubic, perineal, flank, and lower back pain; and, occasionally, a low-grade fever. Most common in women between ages 25 and 60, chronic interstitial cystitis is characterized by Hunner’s ulcers — small, punctate, bleeding lesions in the bladder; it also causes gross hematuria. Because symptoms resemble bladder cancer, this must be ruled out.

Viral cystitis also causes urinary urgency, hematuria, and a fever.

Diabetes insipidus. The result of antidiuretic hormone deficiency, diabetes insipidus usually produces nocturia early in its course. It’s characterized by periodic voiding of moderate to large amounts of urine. Diabetes insipidus can also produce polydipsia and dehydration.

Diabetes mellitus. An early sign of diabetes mellitus, nocturia involves frequent, large voidings. Associated features include daytime polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, frequent urinary tract infections, recurrent yeast infections, vaginitis, weakness, fatigue, weight loss and, possibly, signs of dehydration, such as dry mucous membranes and poor skin turgor.

Hypercalcemic nephropathy. With hypercalcemic nephropathy, nocturia involves the periodic voiding of moderate to large amounts of urine. Related findings include daytime polyuria, polydipsia and, occasionally, hematuria and pyuria.

Prostate cancer. The second leading cause of cancer deaths in men, prostate cancer usually produces no symptoms in the early stages. Later, it produces nocturia characterized by infrequent voiding of moderate amounts of urine. Other characteristic effects include dysuria (most common symptom), difficulty initiating a urine stream, an interrupted urine stream, bladder distention, urinary frequency, weight loss, pallor, weakness, perineal pain, and constipation. Palpation reveals a hard, irregularly shaped, nodular prostate.

Pyelonephritis (acute). Nocturia is common with acute pyelonephritis and is usually characterized by infrequent voiding of moderate amounts of urine, which may appear cloudy. Associated signs and symptoms include a high, sustained fever with chills, fatigue, unilateral or bilateral flank pain, CVA tenderness, weakness, dysuria, hematuria, urinary frequency and urgency, and tenesmus. Occasionally, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and hypoactive bowel sounds may also occur.

Renal failure (chronic). Nocturia occurs relatively early in chronic renal failure and is usually characterized by infrequent voiding of moderate amounts of urine. As the disorder progresses, oliguria or even anuria develops. Other widespread effects of chronic renal failure include fatigue, an ammonia breath odor, Kussmaul’s respirations, peripheral edema, elevated blood pressure, a decreased level of consciousness, confusion, emotional lability, muscle twitching, anorexia, a metallic taste in the mouth, constipation or diarrhea, petechiae, ecchymoses, pruritus, yellowor bronze-tinged skin, nausea, and vomiting.

Other Causes

Drugs. Any drug that mobilizes edematous fluid or produces diuresis (for example, a diuretic or cardiac glycoside) may cause nocturia; obviously, this effect depends on when the drug is administered.

Special Considerations

Patient care includes maintaining fluid balance, ensuring adequate rest, and providing education. Monitor the patient’s vital signs, intake and output, and daily weight; continue to document the frequency of nocturia, the amount, and specific gravity. Plan administration of a diuretic for daytime hours, if possible. Also plan rest periods to compensate for sleep lost because of nocturia.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, which may include routine urinalysis; urine concentration and dilution studies; serum blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and electrolyte levels; and cystoscopy.

Patient Counseling

Explain the importance of reducing fluid intake and voiding before bedtime.

Pediatric Pointers

In children, nocturia may be voluntary or involuntary. The latter is commonly known as enuresis or bedwetting. With the exception of prostate disorders, causes of nocturia are generally the same for children and adults.

However, children with pyelonephritis are more susceptible to sepsis, which may display as a fever, irritability, and poor skin perfusion. In addition, girls may experience vaginal discharge and vulvar soreness or pruritus.

Geriatric Pointers

Postmenopausal women have decreased bladder elasticity, but urine output remains constant, resulting in nocturia.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Nuchal Rigidity

Commonly an early sign of meningeal irritation, nuchal rigidity refers to neck stiffness that prevents flexion. To elicit this sign, attempt to passively flex the patient’s neck and touch his chin to his chest. If nuchal rigidity is present, this maneuver triggers pain and muscle spasms. (Make sure that there’s no cervical spinal misalignment, such as a fracture or dislocation, before testing for nuchal rigidity. Severe spinal cord damage could result.) The patient may also notice nuchal rigidity when he attempts to flex his neck during daily activities. This sign isn’t reliable in children and infants.

Nuchal rigidity may herald life-threatening subarachnoid hemorrhage or meningitis. It may also be a late sign of cervical arthritis, in which joint mobility is gradually lost.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

After eliciting nuchal rigidity, attempt to elicit Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs. Quickly evaluate the patient’s level of consciousness (LOC). Take his vital signs. If you note signs of increased intracranial pressure (ICP), such as increased systolic pressure, bradycardia, and

a widened pulse pressure, start an I.V. line for drug administration and deliver oxygen as necessary. Keep the head of the bed at least as low as 30 degrees. Draw a specimen for routine blood studies such as a complete blood count with a white blood cell count and electrolyte levels.

History and Physical Examination

Obtain a patient history, relying on family members if an altered LOC prevents the patient from responding. Ask about the onset and duration of neck stiffness. Were there precipitating factors? Also ask about associated signs and symptoms, such as a headache, a fever, nausea and vomiting, and motor and sensory changes. Check for a history of hypertension, head trauma, cerebral aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation, endocarditis, recent infection (such as sinusitis or pneumonia), or recent dental work. Then, obtain a complete drug history.

If the patient has no other signs of meningeal irritation, ask about a history of arthritis or neck trauma. Can the patient recall pulling a muscle in his neck? Inspect the patient’s hands for swollen, tender joints, and palpate the neck for pain or tenderness.

Medical Causes

Cervical arthritis. With cervical arthritis, nuchal rigidity develops gradually. Initially, the patient may complain of neck stiffness in the early morning or after a period of inactivity. Stiffness then becomes increasingly severe and frequent. Pain on movement, especially with lateral motion or head turning, is common. Typically, arthritis also affects other joints, especially those in the hands.

Encephalitis. Encephalitis is a viral infection that may cause nuchal rigidity accompanied by other signs of meningeal irritation, such as positive Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs. Usually, nuchal rigidity appears abruptly and is preceded by a headache, vomiting, and a fever. The patient may display a rapidly decreasing LOC, progressing from lethargy to coma within 24 to 48 hours of onset. Associated features include seizures, ataxia, hemiparesis, nystagmus, and cranial nerve palsies, such as dysphagia and ptosis.

Listeriosis. If listeriosis spreads to the nervous system, meningitis may develop. Signs and symptoms include nuchal rigidity, a fever, a headache, and a change in the LOC. Initial signs and symptoms include a fever, myalgia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

GENDER CUE

GENDER CUE

Listeriosis infection during pregnancy may lead to premature delivery, infection of the neonate, or still birth.

Meningitis. Nuchal rigidity is an early sign of meningitis and is accompanied by other signs of meningeal irritation — positive Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs, hyperreflexia and, possibly, opisthotonos. Other early features include a fever with chills, a headache, photophobia, and vomiting. Initially, the patient is confused and irritable; later, he may become stuporous and seizure prone or may slip into a coma. Cranial nerve involvement may cause ocular palsies, facial weakness, and hearing loss. An erythematous papular rash occurs in some forms of viral

meningitis; a purpuric rash may occur in meningococcal meningitis.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage. Nuchal rigidity develops immediately after bleeding into the subarachnoid space. Examination may detect positive Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs. The patient may experience an abrupt onset of a severe headache, photophobia, a fever, nausea and vomiting, dizziness, cranial nerve palsies, and focal neurologic signs, such as hemiparesis or hemiplegia. His LOC deteriorates rapidly, possibly progressing to coma. Signs of increased ICP, such as bradycardia and altered respirations, may also occur.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as computed tomography scans, magnetic resonance imaging, and cervical spinal X-rays.

Monitor the patient’s vital signs, intake and output, and neurologic status closely. Avoid routine administration of opioid analgesics because these may mask signs of increasing ICP. Enforce strict bed rest; keep the head of the bed elevated at least 30 degrees to help minimize ICP.

Assist the patient in finding a comfortable position to obtain adequate rest.

Patient Counseling

Orient the patient, as appropriate, and explain all procedures and diagnostic tests to him and his family. Explain the cause of nuchal rigidity and the treatment plan.

Pediatric Pointers

Tests for nuchal rigidity are generally less reliable in children, especially in infants. In younger children, move the head gently in all directions, observing for resistance. In older children, ask the child to sit upright and touch his chin to his chest. Resistance to this movement may indicate meningeal irritation.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis. Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Nystagmus

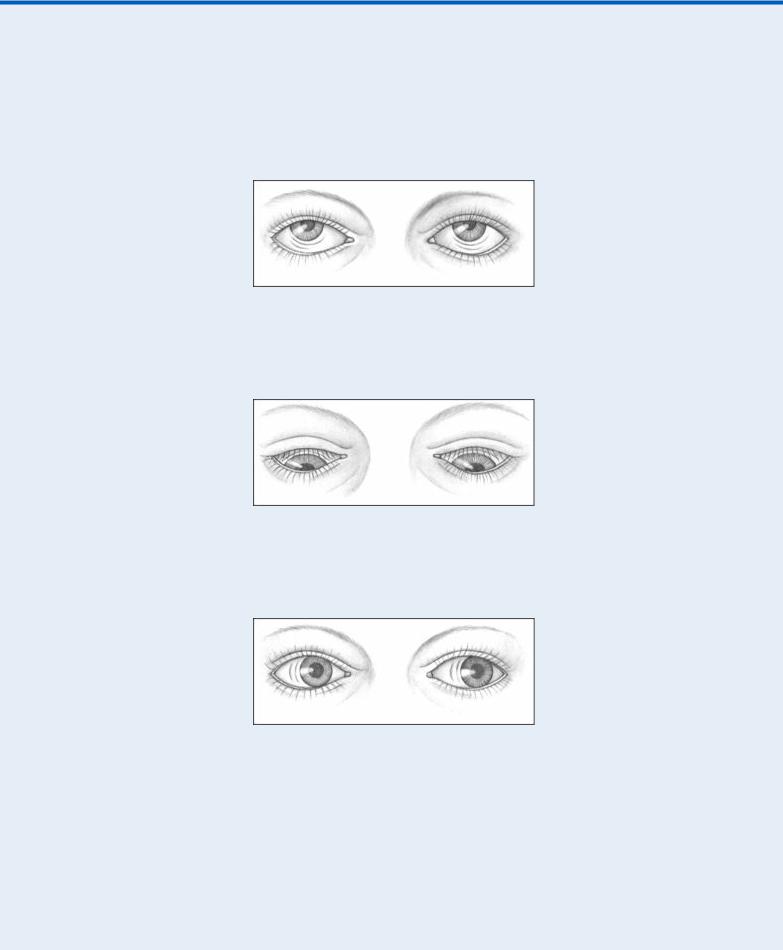

Nystagmus refers to the involuntary oscillations of one or, more commonly, both eyeballs. These oscillations are usually rhythmic and may be horizontal, vertical, rotary, or mixed. They may be transient or sustained and may occur spontaneously or on deviation or fixation of the eyes. Minor degrees of nystagmus at the extremes of gaze are normal. Nystagmus when the eyes are stationary and looking straight ahead is always abnormal. Although nystagmus is fairly easy to identify, the patient may be unaware of it unless it affects his vision.

Nystagmus may be classified as pendular or jerk. Pendular nystagmus consists of horizontal (pendular) or vertical (seesaw) oscillations that are equal in rate in both directions and resemble the movements of a clock’s pendulum. Jerk nystagmus (convergence-retraction, downbeat, and

vestibular), which is more common than pendular nystagmus, has a fast component and then a slow — perhaps unequal — corrective component in the opposite direction. (See Classifying Nystagmus, page 518.)

Classifying Nystagmus

JERK NYSTAGMUS

Convergence-retraction nystagmus refers to the irregular jerking of the eyes back into the orbit during upward gaze. It can indicate midbrain tegmental damage.

Downbeat nystagmus refers to the irregular downward jerking of the eyes during downward gaze. It can signal lower medullary damage.

Vestibular nystagmus, the horizontal or rotary movement of the eyes, suggests vestibular disease or cochlear dysfunction.

PENDULAR NYSTAGMUS

Horizontal, or pendular, nystagmus refers to oscillations of equal velocity around a center point. It can indicate congenital loss of visual acuity or multiple sclerosis.

Vertical, or seesaw, nystagmus is the rapid, seesaw movement of the eyes: one eye appears to rise while the other appears to fall. It suggests an optic chiasm lesion.

Nystagmus is considered a supranuclear ocular palsy — that is, it results from pathology in the visual perceptual area, vestibular system, cerebellum, or brain stem rather than in the extraocular muscles or cranial nerves III, IV, and VI. Its causes are varied and include brain stem or cerebellar lesions, multiple sclerosis, encephalitis, labyrinthine disease, and drug toxicity. Occasionally, nystagmus is entirely normal; it’s also considered a normal response in the unconscious patient during the doll’s eye test (oculocephalic stimulation) or the cold caloric water test (oculovestibular stimulation).

History and Physical Examination

Begin by asking the patient how long he’s had nystagmus. Does it occur intermittently? Does it affect his vision? Ask about recent infection, especially of the ear or respiratory tract, and about head trauma and cancer. Does the patient or anyone in his family have a history of stroke? Then explore associated signs and symptoms. Ask about vertigo, dizziness, tinnitus, nausea or vomiting, numbness, weakness, bladder dysfunction, and fever.

Begin the physical examination by assessing the patient’s level of consciousness (LOC) and vital signs. Be alert for signs of increased intracranial pressure (ICP), such as pupillary changes, drowsiness, elevated systolic pressure, and an altered respiratory pattern. Next, assess nystagmus fully by testing extraocular muscle function: Ask the patient to focus straight ahead and then to follow your finger up, down, and in an “X” across his face. Note when nystagmus occurs as well as its velocity and direction. Finally, test reflexes, motor and sensory function, and the cranial nerves.

Medical Causes

Brain tumor. An insidious onset of jerk nystagmus may occur with tumors of the brain stem and cerebellum. Associated characteristics include deafness, dysphagia, nausea and vomiting, vertigo, and ataxia. Brain stem compression by the tumor may cause signs of increased ICP, such as an altered LOC, bradycardia, a widening pulse pressure, and an elevated systolic blood

pressure.

Encephalitis. With encephalitis, jerk nystagmus is typically accompanied by an altered LOC ranging from lethargy to coma. Usually, it’s preceded by sudden onset of a fever, a headache, and vomiting. Among other features are nuchal rigidity, seizures, aphasia, ataxia, photophobia, and cranial nerve palsies, such as dysphagia and ptosis.

Head trauma. Brain stem injury may cause jerk nystagmus, which is usually horizontal. The patient may also display pupillary changes, an altered respiratory pattern, coma, and decerebrate posture.

Labyrinthitis (acute). Acute labyrinthitis is an inner ear inflammation that causes a sudden onset of jerk nystagmus, accompanied by dizziness, vertigo, tinnitus, nausea, and vomiting. The fast component of the nystagmus is toward the unaffected ear. Gradual sensorineural hearing loss may also occur.

Ménière’s disease. Ménière’s disease is an inner ear disorder that’s characterized by acute attacks of jerk nystagmus, severe nausea and vomiting, dizziness, vertigo, progressive hearing loss, tinnitus, and diaphoresis. Typically, the direction of jerk nystagmus varies from one attack to the next. Attacks may last from 10 minutes to several hours.

Stroke. A stroke involving the posterior inferior cerebellar artery may cause sudden horizontal or vertical jerk nystagmus that may be gaze dependent. Other findings include dysphagia, dysarthria, loss of pain and temperature sensation on the ipsilateral face and contralateral trunk and limbs, ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome (unilateral ptosis, pupillary constriction, and facial anhidrosis), and cerebellar signs, such as ataxia and vertigo. Signs of increased ICP (such as an altered LOC, bradycardia, a widening pulse pressure, and an elevated systolic pressure) may also occur.

Other Causes

Drugs and alcohol. Jerk nystagmus may result from barbiturate, phenytoin, or carbamazepine toxicity or from alcohol intoxication.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as electronystagmography and a cerebral computed tomography scan.

Patient Counseling

Instruct the patient about safety measures and caution him about the importance of avoiding sudden position changes.

Pediatric Pointers

In children, pendular nystagmus may be idiopathic or it may result from early impaired vision associated with such disorders as optic atrophy, albinism, congenital cataracts, or severe astigmatism.

REFERENCES

Ansons, A. M., & Davis, H. (2014). Diagnosis and management of ocular motility disorders. West Sussex, UK: Wiley Blackwell. Biswas, J. , Krishnakumar, S., & Ahuja, S. (2010) . Manual of ocular pathology. New Delhi, India: Jaypee–Highlights Medical

Publishers.

Gerstenblith, A. T., & Rabinowitz, M. P. (2012). The wills eye manual. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Roy, F. H. (2012). Ocular differential diagnosis. Clayton, Panama: Jaypee–Highlights Medical Publishers, Inc.

O

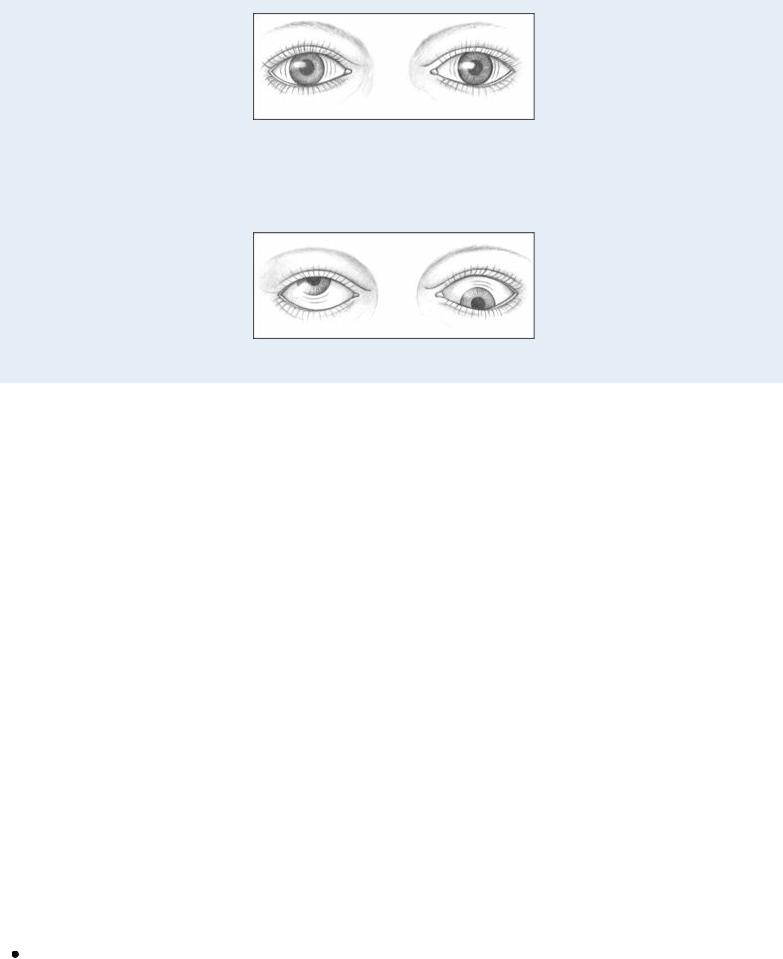

Ocular Deviation

Ocular deviation refers to abnormal eye movement that may be conjugate (both eyes move together) or disconjugate (one eye moves separately from the other). This common sign may result from ocular, neurologic, endocrine, and systemic disorders that interfere with the muscles, nerves, or brain centers governing eye movement. Occasionally, it signals a life-threatening disorder such as a ruptured cerebral aneurysm. (See Ocular Deviation: Its Characteristics and Causes in Cranial Nerve Damage, page 522.)

Normally, eye movement is directly controlled by the extraocular muscles innervated by the oculomotor, trochlear, and abducens nerves (cranial nerves III, IV, and VI). Together, these muscles and nerves direct a visual stimulus to fall on corresponding parts of the retina. Disconjugate ocular deviation may result from unequal muscle tone (nonparalytic strabismus) or muscle paralysis associated with cranial nerve damage (paralytic strabismus). Conjugate ocular deviation may result from disorders that affect the centers in the cerebral cortex and brain stem responsible for conjugate eye movement. Typically, such disorders cause gaze palsy — difficulty moving the eyes in one or more directions.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient displays ocular deviation, take his vital signs immediately and assess him for an altered level of consciousness (LOC) , pupil changes, motor or sensory dysfunction, and a severe headache. If possible, ask the patient’s family about behavioral changes . Is there a history of recent head trauma? Respiratory support may be necessary. Also, prepare the patient for emergency neurologic tests such as a computed tomography (CT) scan.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient isn’t in distress, find out how long he has had the ocular deviation. Is it accompanied by double vision, eye pain, or a headache? Also, ask if he’s noticed associated motor or sensory changes or a fever.

Check for a history of hypertension, diabetes, allergies, and thyroid, neurologic, or muscular disorders. Then obtain a thorough ocular history. Has the patient ever had extraocular muscle imbalance, eye or head trauma, or eye surgery?

During the physical examination, observe the patient for partial or complete ptosis. Does he spontaneously tilt his head or turn his face to compensate for ocular deviation? Check for eye redness or periorbital edema. Assess the patient’s visual acuity, and then evaluate extraocular muscle function by testing the six cardinal fields of gaze.

Medical Causes

Brain tumor. The nature of ocular deviation depends on the site and extent of the tumor. Associated signs and symptoms include headaches that are most severe in the morning, behavioral changes, memory loss, dizziness, confusion, vision loss, motor and sensory dysfunction, aphasia and, possibly, signs of hormonal imbalance. The patient’s LOC may slowly deteriorate from lethargy to coma. Late signs include papilledema, vomiting, increased systolic blood pressure, widening pulse pressure, and decorticate posture.

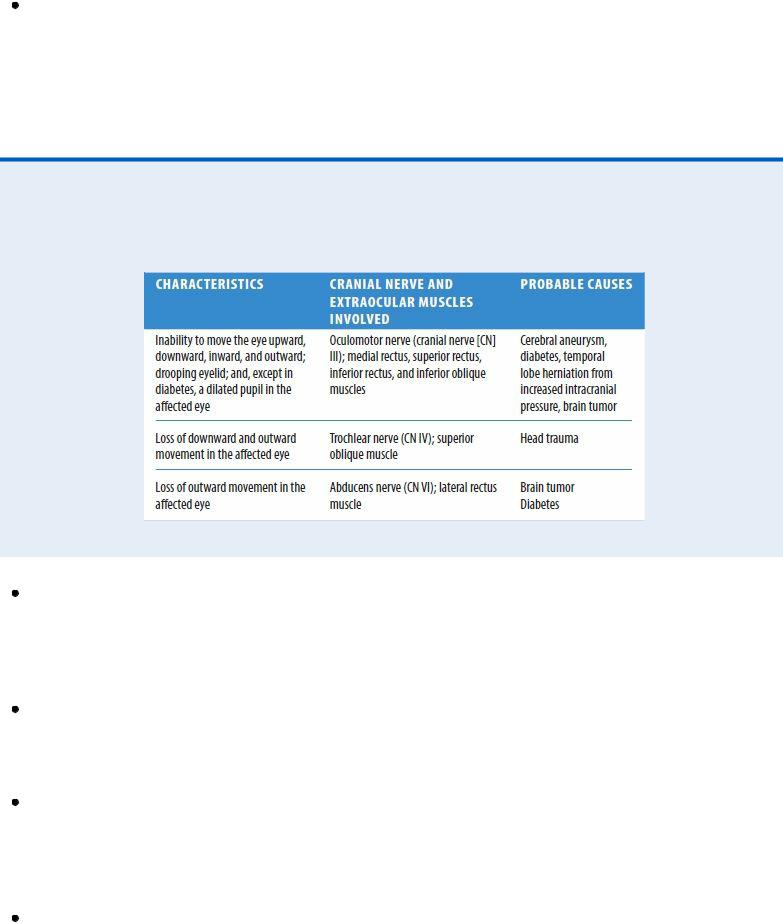

Ocular Deviation: Its Characteristics and Causes in Cranial

Nerve Damage

Cavernous sinus thrombosis. With cavernous sinus thrombosis, ocular deviation may be accompanied by diplopia, photophobia, exophthalmos, orbital and eyelid edema, corneal haziness, diminished or absent pupillary reflexes, and impaired visual acuity. Other features include a high fever, a headache, malaise, nausea and vomiting, seizures, and tachycardia. Retinal hemorrhage and papilledema are late signs.

Diabetes mellitus. A leading cause of isolated third cranial nerve palsy, especially in the middle-aged patient with long-standing mild diabetes, diabetes mellitus may cause ocular deviation and ptosis. Typically, the patient also complains of the sudden onset of diplopia and pain.

Encephalitis. Encephalitis causes ocular deviation and diplopia in some cases. Typically, it begins abruptly with a fever, a headache, and vomiting, followed by signs of meningeal irritation (for example, nuchal rigidity) and neuronal damage (for example, seizures, aphasia, ataxia, hemiparesis, cranial nerve palsies, and photophobia). The patient’s LOC may rapidly deteriorate from lethargy to coma within 24 to 48 hours after onset.

Head trauma. The nature of ocular deviation depends on the site and extent of head trauma. The patient may have visible soft tissue injury, bony deformity, facial edema, and clear or bloody otorrhea or rhinorrhea. Besides these obvious signs of trauma, he may also develop blurred vision, diplopia, nystagmus, behavioral changes, a headache, motor and sensory dysfunction, and a decreased LOC that may progress to coma. Signs of increased intracranial pressure — such as