Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

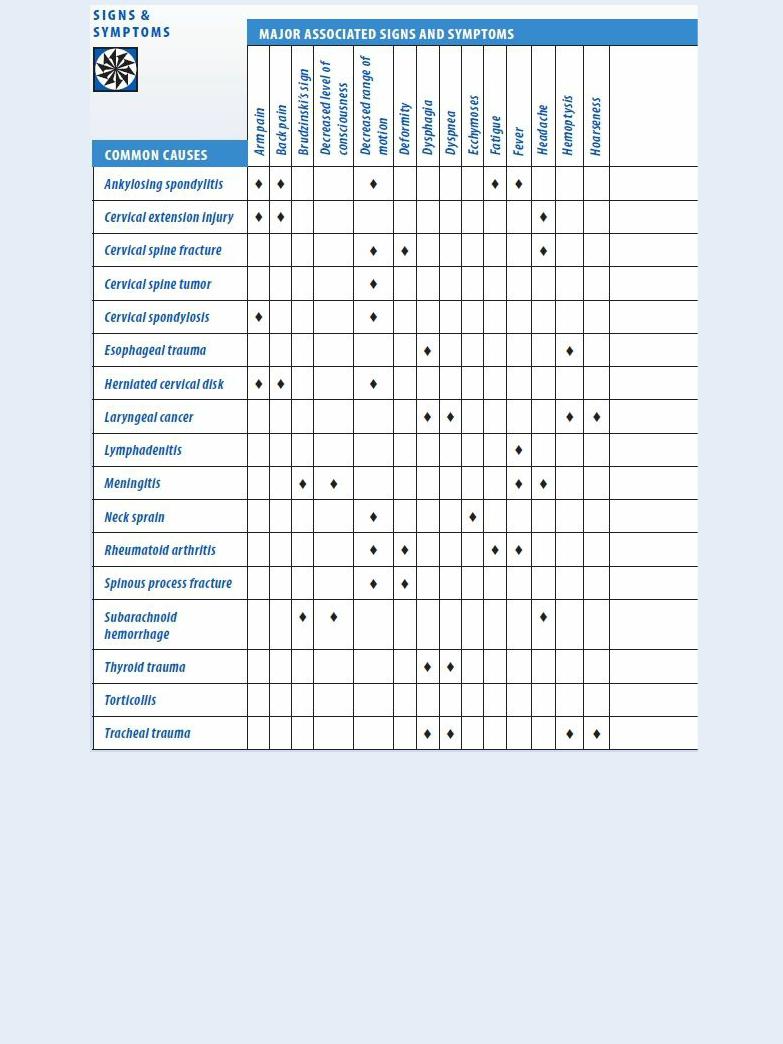

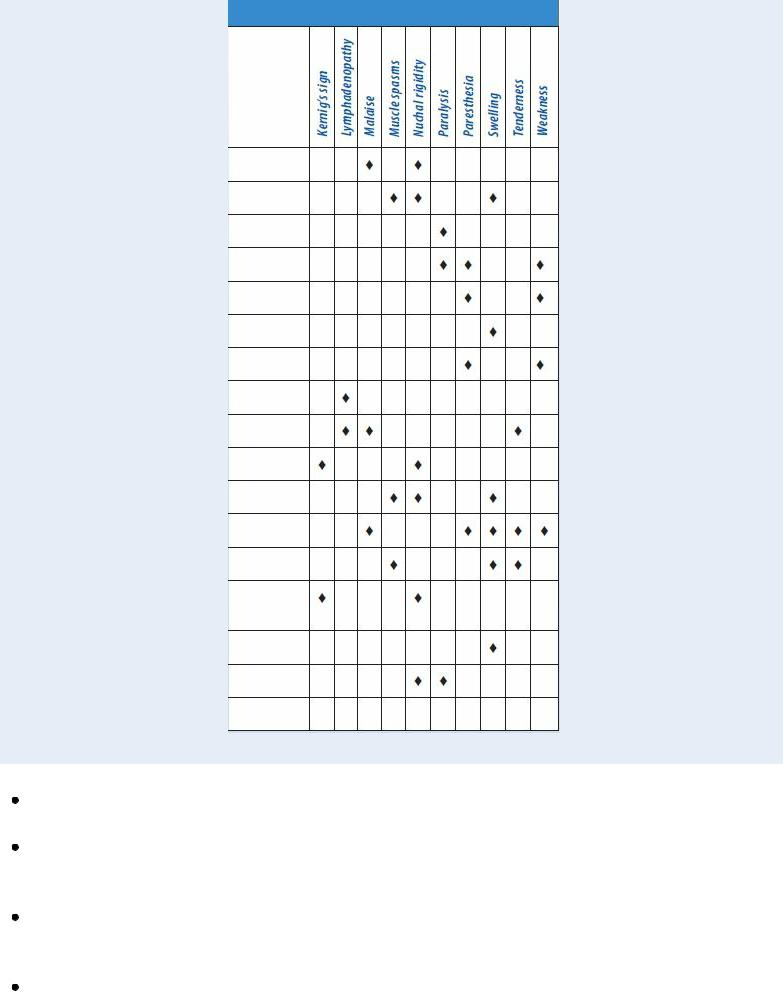

Cervical extension injury. Anterior or posterior neck pain may develop within hours or days following a whiplash injury. Anterior pain usually diminishes within several days, but posterior pain persists and may even intensify. Associated findings include tenderness, swelling and nuchal rigidity, arm or back pain, an occipital headache, muscle spasms, visual blurring, and unilateral miosis on the affected side.

Cervical spine fracture. Fracture at C1 to C4 can cause sudden death; survivors may experience severe neck pain that restricts all movement, an intense occipital headache, quadriplegia, deformity, and respiratory paralysis.

Cervical spine tumor. Metastatic tumors typically produce persistent neck pain that increases with movement and isn’t relieved by rest; primary tumors cause mild to severe pain along a specific nerve root. Other findings depend on the lesions and may include paresthesia, arm and leg weakness that progresses to atrophy and paralysis, and bladder and bowel incontinence.

Cervical spondylosis. Cervical spondylosis is a degenerative process that produces posterior neck pain that restricts movement and is aggravated by it. Pain may radiate down either arm and may accompany paresthesia, weakness, and stiffness.

Esophageal trauma. An esophageal mucosal tear or a pulsion diverticulum may produce mild neck pain, chest pain, edema, hemoptysis, and dysphagia.

Herniated cervical disk. A herniated cervical disk characteristically causes variable neck pain that restricts movement and is aggravated by it. It also causes referred pain along a specific dermatome, paresthesia and other sensory disturbances, and arm weakness.

Laryngeal cancer. Neck pain that radiates to the ear develops late in laryngeal cancer. The patient may also develop dysphagia, dyspnea, hemoptysis, stridor, hoarseness, and cervical lymphadenopathy.

Neck Pain: Common Causes and Associated Findings

Lymphadenitis. With lymphadenitis, enlarged and inflamed cervical lymph nodes cause acute pain and tenderness. A fever, chills, and malaise may also occur.

Meningitis. Neck pain may accompany characteristic nuchal rigidity. Related findings include a fever, a headache, photophobia, positive Brudzinski’s and Kernig’s signs, and a decreased level of consciousness (LOC).

Neck sprain. Minor sprains typically produce pain, slight swelling, stiffness, and restricted ROM. Ligament rupture causes pain, marked swelling, ecchymosis, muscle spasms, and nuchal rigidity with head tilt.

Rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatoid arthritis usually affects peripheral joints, but it can also involve the cervical vertebrae. Acute inflammation may cause moderate to severe pain that radiates along a specific nerve root; increased warmth, swelling, and tenderness in involved

joints; stiffness, restricting ROM; paresthesia and muscle weakness; low-grade fever; anorexia; malaise; fatigue; and possible neck deformity. Some pain and stiffness remain after the acute phase.

Spinous process fracture. A fracture near the cervicothoracic junction produces acute pain radiating to the shoulders. Associated findings include swelling, exquisite tenderness, restricted ROM, muscle spasms, and deformity.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage. Subarachnoid hemorrhage is a life-threatening condition that may cause moderate to severe neck pain and rigidity, a headache, and a decreased LOC. Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs are present. The patient may describe the headache as, “the worst headache of my life.”

Thyroid trauma. Besides mild to moderate neck pain, thyroid trauma may cause local swelling and ecchymosis. If a hematoma forms, it can cause dyspnea.

Torticollis. Torticollis is a neck deformity in which severe neck pain accompanies recurrent unilateral stiffness and muscle spasms that produce a characteristic head tilt.

Tracheal trauma. A fracture of the tracheal cartilage, a life-threatening condition, produces moderate to severe neck pain and respiratory difficulty.

Torn tracheal mucosa produces mild to moderate pain and may result in airway occlusion, hemoptysis, hoarseness, and dysphagia.

Special Considerations

Promote patient comfort by giving an anti-inflammatory and an analgesic, as needed. Assist the patient to find positions that make him most comfortable. Prepare him for diagnostic tests, such as X- rays, a computed tomography scan, blood tests, and cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

Patient Counseling

Explain any activities the patient needs to limit or avoid, and provide reinforcement for prescribed exercises. Teach the patient how to apply a cervical collar, if needed.

Pediatric Pointers

The most common causes of neck pain in children are meningitis and trauma. A rare cause of neck pain is congenital torticollis.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Sarwark, J. F. (2010). Essentials of musculoskeletal care. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Nipple Discharge

Nipple discharge can occur spontaneously or can be elicited by nipple stimulation. It’s characterized as intermittent or constant, unilateral or bilateral, and by color, consistency, and composition. Its

incidence increases with age and parity. This sign rarely occurs (but is more likely to be pathologic) in men and in nulligravid, regularly menstruating women. It’s relatively common and typically normal in parous women. A thick, grayish discharge — benign epithelial debris from inactive ducts — can usually be elicited in middle-age parous women. Colostrum, a thin, yellowish or milky discharge, commonly occurs in the last weeks of pregnancy.

Nipple discharge can signal serious underlying disease, particularly when accompanied by other breast changes. Significant causes include endocrine disorders, cancer, certain drugs, and blocked lactiferous ducts.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient when she first noticed the discharge, and determine its duration, extent, quantity, color, consistency, and smell, if any. Has she had other nipple and breast changes, such as pain, tenderness, itching, warmth, changes in contour, and lumps? If she reports a lump, question her about its onset, location, size, and consistency.

Obtain a complete gynecologic and obstetric history, and determine her normal menstrual cycle and the date of her last period. Ask if she experiences breast swelling and tenderness, bloating, irritability, headaches, abdominal cramping, nausea, or diarrhea before or during menses. Note the number, date, and outcome of her pregnancies and, if she breast-fed, the approximate time of her last lactation. Also, check for risk factors of breast cancer — family history, previous or current malignancies, nulliparity or first pregnancy after age 30, early menarche, or late menopause.

Start your physical examination by characterizing the discharge. If the discharge isn’t frank, try to elicit it. (See Eliciting Nipple Discharge.) Then examine the nipples and breasts with the patient in four different positions: sitting with her arms at her sides; with her arms overhead; with her hands pressing on her hips; and leaning forward so her breasts are suspended. Check for nipple deviation, flattening, retraction, redness, asymmetry, thickening, excoriation, erosion, or cracking. Inspect her breasts for asymmetry, irregular contours, dimpling, erythema, and peau d’orange. With the patient in a supine position, palpate the breasts and axillae for lumps, giving special attention to the areolae. Note the size, location, delineation, consistency, and mobility of any lump you find.

Is the patient taking hormones (hormonal contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy)? Is the discharge spontaneous, or does it have to be expressed?

Eliciting Nipple Discharge

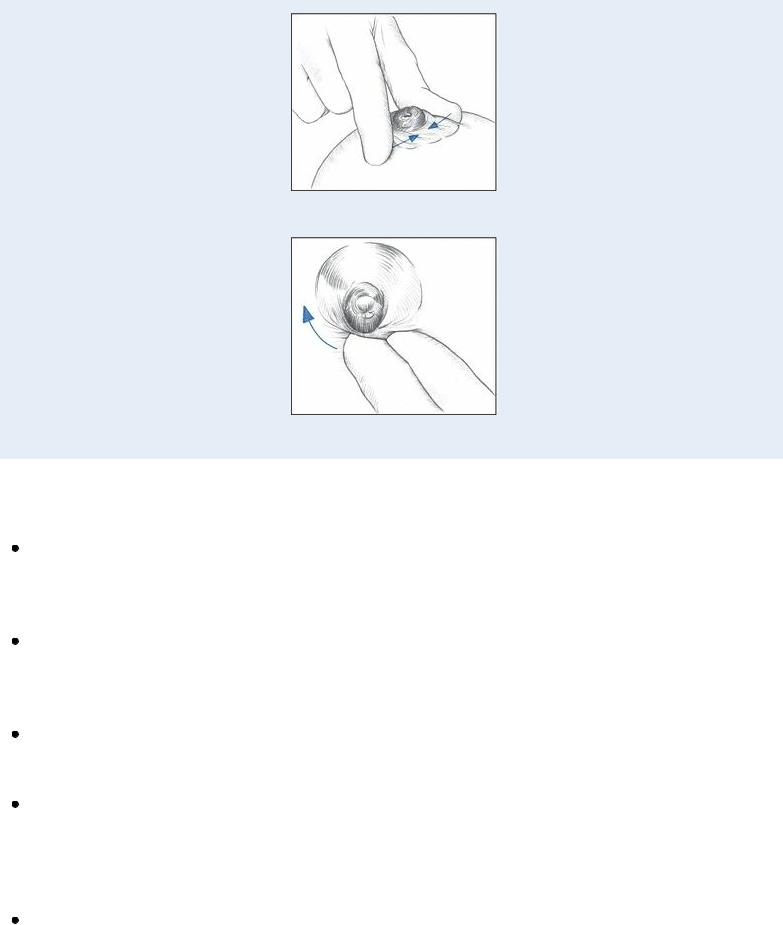

If the patient has a history or evidence of nipple discharge, you can attempt to elicit it during your examination. Help the patient into a supine position, and gently squeeze her nipple between your thumb and index finger; note any discharge through the nipple. Then place your fingers on the areola, as shown, and palpate the entire areolar surface, watching for a discharge through areolar ducts.

Medical Causes

Breast abscess. Breast abscess, most common in breast-feeding women, may produce a thick, purulent discharge from a cracked nipple or infected duct. Associated findings include an abrupt onset of a high fever with chills; breast pain, tenderness, and erythema; a palpable soft nodule or generalized induration; and, possibly, nipple retraction.

Breast cancer. Breast cancer may cause bloody, watery, or purulent discharge from a normalappearing nipple. Characteristic findings include a hard, irregular, fixed lump; erythema; dimpling; peau d’orange; changes in contour; nipple deviation, flattening, or retraction; axillary lymphadenopathy; and, possibly, breast pain.

Choriocarcinoma. Galactorrhea (a white or grayish milky discharge) may result from this highly malignant neoplasm, which can follow pregnancy. Other characteristics include persistent uterine bleeding and bogginess after delivery or curettage and vaginal masses.

Intraductal papilloma. Intraductal papilloma is the primary cause of nipple discharge in the nonpregnant, non–breast-feeding woman. Unilateral serous, serosanguineous, or bloody nipple discharge — usually from only one duct — is its predominant sign. Discharge may be intermittent or profuse and constant and can usually be stimulated by gentle pressure around the areola. Subareolar nodules, breast pain, and tenderness may occur.

Mammary duct ectasia. A thick, sticky, grayish discharge from multiple ducts may be the first sign of mammary duct ectasia. The discharge may be bilateral and is usually spontaneous. Other findings include a rubbery, poorly delineated lump beneath the areola, with a blue-green discoloration of the overlying skin; nipple retraction; and redness, swelling, tenderness, and burning pain in the areola and nipple.

Paget’s disease. With Paget’s disease, serous or bloody discharge emits from denuded skin on the nipple, which is red, intensely itchy and, possibly, eroded or excoriated. The discharge is usually unilateral.

Prolactin-secreting pituitary tumor. Bilateral galactorrhea may occur with prolactin-secreting pituitary tumor. Other findings include amenorrhea, infertility, decreased libido and vaginal secretions, headaches, and blindness.

Proliferative (fibrocystic) breast disease. Proliferative breast disease is a benign disorder that occasionally causes a bilateral clear, milky, or straw-colored discharge, which is rarely purulent or bloody. Multiple round, soft, tender nodules are usually palpable in both breasts, although they may occur singly. Usually, nodules are mobile and are located in the upper outer quadrant. Nodule size, tenderness, and discharge increase during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Symptoms then regress after menses.

Other Causes

Drugs. Galactorrhea can be caused by psychotropic agents, particularly phenothiazines and tricyclic antidepressants; some antihypertensives (reserpine and methyldopa); hormonal contraceptives; cimetidine; metoclopramide; and verapamil.

Surgery. Chest wall surgery may stimulate the thoracic nerves, causing intermittent bilateral galactorrhea.

Special Considerations

Although nipple discharge is usually insignificant, it can be frightening to the patient. Help relieve her anxiety by clearly explaining the nature and origin of her discharge. Apply a breast binder, which may reduce discharge by eliminating nipple stimulation.

Diagnostic tests may include tissue biopsy (if a breast lump is found), cytologic study of the discharge, mammography, ultrasonography, transillumination, and serum prolactin level.

Patient Counseling

Explain the importance of being aware of discharge characteristics and when to seek medical attention. Discuss the importance of breast self-examinations, medical appointments, and mammograms.

Pediatric Pointers

Nipple discharge in children and adolescents is rare. When it does occur, it’s almost always nonpathologic, as in the bloody discharge that sometimes accompanies the onset of menarche. Infants of both sexes may experience a milky breast discharge beginning 3 days after birth and lasting up to 2 weeks due to maternal hormonal influences.

Geriatric Pointers

In postmenopausal women, breast changes are considered malignant until proven otherwise.

REFERENCES

Aliotta, H. M., & Schaeffer, N. J. (2013). Breast conditions. In K. D. Schuiling, & F. E. Likis (Eds.), Women’s gynecologic health (pp. 377–401). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Nipple Retraction

Nipple retraction, the inward displacement of the nipple below the level of surrounding breast tissue, may indicate an inflammatory breast lesion or cancer. It results from scar tissue formation within a lesion or large mammary duct. As the scar tissue shortens, it pulls adjacent tissue inward, causing nipple deviation, flattening and, finally, retraction.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient when she first noticed the nipple retraction. Has she experienced other nipple changes, such as itching, discoloration, discharge, or excoriation? Has she noticed breast pain, lumps, redness, swelling, or warmth? Obtain a history, noting risk factors of breast cancer, such as a family history or previous malignancy.

Carefully examine both nipples and breasts with the patient sitting upright with her arms at her sides, with her hands pressing on her hips, with her arms overhead, and leaning forward so her breasts hang. Look for redness, excoriation, and discharge; nipple flattening and deviation; and breast asymmetry, dimpling, or contour differences. (See Differentiating Nipple Retraction from Inversion , page 512.)

Try to evert the nipple by gently squeezing the areola. With the patient in a supine position, palpate both breasts for lumps, especially beneath the areola. Mold breast skin over the lump or gently pull it up toward the clavicle, looking for accentuated nipple retraction. Also, palpate axillary lymph nodes.

Medical Causes

Breast abscess. Breast abscess, most common in breast-feeding women, occasionally produces unilateral nipple retraction. More common findings include a high fever with chills; breast pain, erythema, and tenderness; breast induration or a soft mass; and cracked, sore nipples, possibly with a purulent discharge.

Breast cancer. Unilateral nipple retraction is commonly accompanied by a hard, fixed, nontender nodule beneath the areola as well as other breast nodules. Other nipple changes include itching, burning, erosion, and watery or bloody discharge. Breast changes commonly include dimpling, altered contour, peau d’orange, ulceration, tenderness (possibly pain), redness, and warmth. Axillary lymph nodes may be enlarged.

Mammary duct ectasia. Nipple retraction commonly occurs along with a poorly defined, rubbery nodule beneath the areola, with a blue-green skin discoloration; areolar burning, itching, swelling, tenderness, and erythema; and nipple pain with a thick, sticky, grayish, multiductal discharge.

Mastitis. Nipple retraction, deviation, cracking, or flattening may occur in mastitis with a firm and indurated or tender, flocculent, discrete breast nodule; warmth; erythema; tenderness; and

edema. Fatigue, high fevers, and chills may also be present.

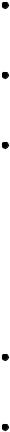

Differentiating Nipple Retraction from Inversion

Nipple retraction is sometimes confused with nipple inversion, a common abnormality that’s congenital in many patients and doesn’t usually signal underlying disease. A retracted nipple appears flat and broad, whereas an inverted nipple can be pulled out from the sulcus where it hides.

NIPPLE RETRACTION

NIPPLE INVERSION

Other Causes

Surgery. Previous breast surgery may cause underlying scarring and retraction.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, including mammography, cytology of nipple discharge, and biopsy.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient to perform monthly breast self-examination. Advise the patient to seek medical attention for breast changes. Explain the cause of the nipple retraction and the treatment plan.

Pediatric Pointers

Nipple retraction doesn’t occur in prepubescent females.

Reference

Aliotta, H. M., & Schaeffer, N. J. (2013). Breast conditions. In Women’s gynecologic health (pp. 377–401). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nocturia

Nocturia — excessive urination at night — may result from disruption of the normal diurnal pattern of urine concentration or from overstimulation of the nerves and muscles that control urination. Normally, more urine is concentrated during the night than during the day. As a result, most people excrete three to four times more urine during the day and can sleep for 6 to 8 hours during the night without being awakened. The patient with nocturia may awaken one or more times during the night to empty his bladder and excrete 700 mL or more of urine.

Although nocturia usually results from renal and lower urinary tract disorders, it may result from certain cardiovascular, endocrine, and metabolic disorders. This common sign may also result from drugs that induce diuresis, particularly when they’re taken at night, and from drinking large quantities of fluids, especially caffeinated beverages or alcohol, at bedtime.

History and Physical Examination

Begin by exploring the history of the patient’s nocturia. When did it begin? How often does it occur? Can the patient identify a specific pattern? Precipitating factors? Also, note the volume of urine voided. Ask the patient about changes in the color, odor, or consistency of his urine. Has the patient changed his usual pattern or volume of fluid intake? Next, explore associated symptoms. Ask about pain or burning on urination, difficulty initiating a urine stream, urinary urgency, costovertebral angle (CVA) tenderness, and flank, upper abdominal, or suprapubic pain.

Determine if the patient or his family has a history of renal or urinary tract disorders or endocrine and metabolic diseases, particularly diabetes. Is the patient taking a drug that increases urine output, such as a diuretic, a cardiac glycoside, or an antihypertensive?

Focus your physical examination on palpating and percussing the kidneys, CVA, and bladder. Carefully inspect the urinary meatus. Inspect a urine specimen for color, odor, and the presence of sediment.

Medical Causes

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Common in men older than age 50, BPH produces nocturia when significant urethral obstruction develops. Typically, it causes frequency, hesitancy, incontinence, reduced force and caliber of the urine stream, and, possibly, hematuria. Oliguria may also occur. Palpation reveals a distended bladder and an enlarged prostate. The patient may also complain of lower abdominal fullness, perineal pain, and constipation. Obstruction may lead to renal failure.

Cystitis. All three forms of cystitis may cause nocturia marked by frequent, small voidings and