Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

History and Physical Examination

If the patient reports a headache, ask him to describe its characteristics and location. How often does he get a headache? How long does a typical headache last? Try to identify precipitating factors, such as certain foods or exposure to bright lights. Ask what helps to relieve the headache. Is the patient under stress? Has he had trouble sleeping?

Clinical Features of Headache

The International Headache Society has developed criteria for the diagnosis of a number of different headache types. The differentiating characteristics for some of the common headaches are listed here.

MIGRAINES WITHOUT AN AURA

Previously called common migraines or hemicrania simplex, migraine headaches without an aura are diagnosed when the patient has five attacks that include these symptoms:

Untreated or unsuccessfully treated headache lasting 4 to 72 hours

Two of the following: pain that's unilateral, pulsating, moderate or severe in intensity, or aggravated by activity

Nausea, vomiting, photophobia, or phonophobia

MIGRAINES WITH AN AURA

Previously called classic, classical, ophthalmic, hemiplegic, or aphasic migraines, migraine headaches with an aura are diagnosed when the patient has at least two attacks with three of these characteristics:

One or more reversible aura symptoms (indicates focal cerebral cortical or brain stem dysfunction)

One or more aura symptoms that develop over more than 4 minutes or two or more symptoms that occur in succession

An aura symptom that lasts less than 60 minutes (per symptom)

A headache that begins before, occurs with, or follows an aura with a free interval of less than 60 minutes

Migraines with an aura must also have one of these characteristics to be classified as a typical aura:

Homonymous visual disturbance

Unilateral paresthesia, numbness, or both

Unilateral weakness

Aphasia or other speech difficulty

Migraines also have one of these characteristics:

The history and physical and neurologic examinations are negative for a disorder. Examinations suggest a disorder that's ruled out by appropriate investigation.

A disorder is present, but migraines don't occur for the first time in relation to the disorder.

TENSION-TYPE HEADACHES

In contrast to migraines, episodic tension-type headaches are diagnosed when the headache occurs on fewer than 180 days per year or the patient has fewer than 15 headaches per month and these characteristics are present:

A headache lasting from 30 minutes to 7 days

Pain that's pressing or tightening in quality, mild to moderate, bilateral, and not aggravated by activity

Photophobia or phonophobia occurring sometimes but usually not nausea or vomiting

CLUSTER HEADACHES

Cluster headaches are a treatable type of vascular headache syndrome. Characteristics include the following:

Episodic type (more common) — one to three short-lived attacks of periorbital pain per day over a 4- to 8-week period followed by a pain-free interval averaging 1 year

Chronic type — occurring after an episodic pattern is established

Unilateral pain occurring without warning, reaching a crescendo within 5 minutes, and described as excruciating and deep

Attacks lasting from 30 minutes to 2 hours

Associated symptoms — may include tearing, reddening of the eye, nasal stuffiness, kid ptosis, and nausea

Take a drug and alcohol history, and ask about head trauma within the past 4 weeks. Has the patient recently experienced nausea, vomiting, photophobia, or visual changes? Does he feel drowsy, confused, or dizzy? Has he recently developed seizures or does he have a history of seizures?

Begin the physical examination by evaluating the patient’s level of consciousness (LOC). Then check his vital signs. Be alert for signs of increased ICP — a widened pulse pressure, bradycardia, an altered respiratory pattern, and increased blood pressure. Check pupil size and response to light, and note any neck stiffness.

Medical Causes

Anthrax (cutaneous). Along with a macular papular lesion that develops into a vesicle and finally a painless ulcer, headache, lymphadenopathy, fever, and malaise may occur. Arteriovenous malformations. Less common than cerebral aneurysms, vascular malformations usually result from developmental defects of the cerebral veins and arteries. Although many are present from birth, they manifest in adulthood with a triad of symptoms: headache, hemorrhage, and seizures.

Brain abscess. With brain abscess, the headache is localized to the abscess site. Usually, it intensifies over a few days and is aggravated by straining. Accompanying the headache may be nausea, vomiting, and focal or generalized seizures. The patient’s LOC varies from drowsiness to deep stupor. Depending on the abscess site, associated signs and symptoms may include aphasia, impaired visual acuity, hemiparesis, ataxia, tremors, and personality changes. Signs of infection, such as fever and pallor, usually develop late; however, if the abscess remains encapsulated, these signs may not appear.

Brain tumor. Initially, a tumor causes a localized headache near the tumor site; as the tumor grows, the headache becomes generalized. The pain is usually intermittent, deep seated, dull, and most intense in the morning. It’s aggravated by coughing, stooping, Valsalva’s maneuver, and changes in head position and relieved by sitting and rest. Associated signs and symptoms include personality changes, an altered LOC, motor and sensory dysfunction and, eventually, signs of increased ICP, such as vomiting, increased systolic blood pressure, and a widened pulse pressure.

Cerebral aneurysm (ruptured). Ruptured cerebral aneurysm is a life-threatening disorder that’s characterized by a sudden, excruciating headache, which may be unilateral and usually peaks within minutes of the rupture. The patient may lose consciousness immediately or display a variably altered LOC. Depending on the severity and location of the bleeding, he may also exhibit nausea and vomiting; signs and symptoms of meningeal irritation, such as nuchal rigidity and blurred vision; hemiparesis; and other features.

Ebola virus. A headache is usually abrupt in onset, commonly occurring on the 5th day of illness. Additionally, the patient has a history of malaise, myalgia, a high fever, diarrhea, abdominal pain, dehydration, and lethargy. A maculopapular skin rash develops between the fifth and seventh days of the illness. Other possible findings include pleuritic chest pain; a dry, hacking cough; pronounced pharyngitis; hematemesis; melena; and bleeding from the nose, gums, and vagina. Death usually occurs in the second week of the illness, preceded by severe blood loss and shock.

Encephalitis. A severe, generalized headache is characteristic with encephalitis. Within 48 hours, the patient’s LOC typically deteriorates — perhaps from lethargy to coma. Associated signs and symptoms include a fever, nuchal rigidity, irritability, seizures, nausea and vomiting, photophobia, cranial nerve palsies such as ptosis, and focal neurologic deficits, such as hemiparesis and hemiplegia.

Epidural hemorrhage (acute). Head trauma and a sudden, brief loss of consciousness usually precede acute epidural hemorrhage, which causes a progressively severe headache that’s accompanied by nausea and vomiting, bladder distention, confusion, and then a rapid decrease in the patient’s LOC. Other signs and symptoms include unilateral seizures, hemiparesis, hemiplegia, a high fever, a decreased pulse rate and bounding pulse, a widened pulse pressure, increased blood pressure, a positive Babinski’s reflex, and decerebrate posture.

If the patient slips into a coma, his respirations deepen and become stertorous, then shallow and irregular, and eventually they cease. Pupil dilation may occur on the same side as the hemorrhage.

Glaucoma (acute angle-closure). Glaucoma is an ophthalmic emergency that may cause an excruciating headache as well as acute eye pain, blurred vision, halo vision, nausea, and vomiting. Assessment reveals conjunctival injection, a cloudy cornea, and a moderately dilated,

fixed pupil.

Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema distinguishes hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, a viral disease, which was first reported in the United States in 1993. Common reasons for seeking treatment include flulike signs and symptoms — headache, myalgia, fever, nausea, vomiting, and a cough — followed by respiratory distress. Fever, hypoxia, and (in some patients) serious hypotension typify the hospital course. Other signs and symptoms include a rising respiratory rate (28 breaths/minute or more) and an increased heart rate (120 beats/minute or more).

Hypertension. Hypertension may cause a slightly throbbing occipital headache on awakening that decreases in severity during the day. However, if the patient’s diastolic blood pressure exceeds 120 mm Hg, the headache remains constant. Associated signs and symptoms include an atrial gallop, restlessness, confusion, nausea and vomiting, blurred vision, seizures, and an altered LOC.

Influenza. A severe generalized or frontal headache usually begins suddenly with the flu. Accompanying signs and symptoms may last for 3 to 5 days and include stabbing retro-orbital pain, weakness, diffuse myalgia, fever, chills, coughing, rhinorrhea and, occasionally, hoarseness.

Listeriosis. Signs and symptoms of listeriosis include fever, myalgia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. If the infection spreads to the nervous system, meningitis may develop. These signs and symptoms include headache, nuchal rigidity, fever, and a change in the patient’s LOC.

GENDER CUE

GENDER CUE

Infections during pregnancy may lead to premature delivery, infection of the neonate, or stillbirth.

Meningitis. Meningitis is marked by the sudden onset of a severe, constant, generalized headache that worsens with movement. Associated signs include nuchal rigidity, positive Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs, hyperreflexia, and, possibly, opisthotonos. A fever occurs early with meningitis and may be accompanied by chills. As ICP increases, vomiting and, occasionally, papilledema develop. Other features include an altered LOC, seizures, ocular palsies, facial weakness, and hearing loss.

Plague (Yersinia pestis). The pneumonic form of the plague causes a sudden onset of a headache, chills, fever, myalgia, a productive cough, chest pain, tachypnea, dyspnea, hemoptysis, respiratory distress, and cardiopulmonary insufficiency.

Postconcussional syndrome. A generalized or localized headache may develop 1 to 30 days after head trauma and last for 2 to 3 weeks. This characteristic symptom may be described as an aching, pounding, pressing, stabbing, or throbbing pain. The patient’s neurologic examination is normal, but he may experience giddiness or dizziness, blurred vision, fatigue, insomnia, an inability to concentrate, and noise and alcohol intolerance.

Signs and symptoms of this disease include a severe headache, fever, chills, malaise, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. The fever may last for up to 2 weeks, and in severe cases, the patient

may develop hepatitis or pneumonia.

Q fever. Signs and symptoms of Q fever include severe headaches, fever, chills, malaise, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Fever may last for up to 2 weeks, and in severe cases, the patient may develop hepatitis or pneumonia.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). SARS is an acute infectious disease of unknown etiology; however, a novel coronavirus has been implicated as a possible cause. Although most cases have been reported in Asia (China, Vietnam, Singapore, Thailand), cases have been documented in Europe and North America. The incubation period is 2 to 7 days, and the illness generally begins with a fever (usually greater than 100.4°F [38°C]). Other symptoms include a headache; malaise; a dry, nonproductive cough; and dyspnea. The severity of the illness is highly variable, ranging from mild illness to pneumonia and, in some cases, progressing to respiratory failure and death.

Smallpox (variola major). Initial signs and symptoms of smallpox include a severe headache, backache, abdominal pain, a high fever, malaise, prostration, and a maculopapular rash on the mucosa of the mouth, pharynx, face, and forearms, and then the trunk and legs. The rash becomes vesicular, then pustular, and finally crusts and scabs, leaving a pitted scar. In fatal cases, death results from encephalitis, extensive bleeding, or secondary infection.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage. Subarachnoid hemorrhage commonly produces a sudden, violent headache along with nuchal rigidity, nausea and vomiting, seizures, dizziness, ipsilateral pupil dilation, and an altered LOC that may rapidly progress to coma. The patient also exhibits positive Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs, photophobia, blurred vision and, possibly, a fever. Focal signs and symptoms (such as hemiparesis, hemiplegia, sensory or vision disturbances, and aphasia) and signs of elevated ICP (such as bradycardia and increased blood pressure) may also occur.

Subdural hematoma. Typically associated with head trauma, acute and chronic subdural hematomas may cause a headache and decreased LOC. With acute subdural hematoma, head trauma also produces drowsiness, confusion, and agitation that may progress to coma. Later findings include signs of increased ICP and focal neurologic deficits such as hemiparesis.

Chronic subdural hematoma produces a dull, pounding headache that fluctuates in severity and is located over the hematoma. Weeks or months after the initial head trauma, the patient may experience giddiness, personality changes, confusion, seizures, and a progressively worsening LOC. Late signs may include unilateral pupil dilation, sluggish pupil reaction to light, and ptosis.

Tularemia. Signs and symptoms following inhalation of the bacterium Francisella tularensis include an abrupt onset of a headache, a fever, chills, generalized myalgia, a nonproductive cough, dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and empyema.

Typhus. Initial symptoms of typhus include a headache, myalgia, arthralgia, and malaise followed by an abrupt onset of chills, a fever, nausea, and vomiting. A maculopapular rash may be present in some cases.

West Nile encephalitis. West Nile encephalitis is a brain infection that’s caused by West Nile virus, a mosquito-borne Flavivirus commonly found in Africa, West Asia, the Middle East, and, rarely, North America. Mild infection is common; signs and symptoms include a fever, a headache, and body aches, commonly with a skin rash and swollen lymph glands. More severe

infection is marked by a high fever, a headache, neck stiffness, stupor, disorientation, coma, tremors, occasional seizures, paralysis and, rarely, death.

Other Causes

Diagnostic tests. A lumbar puncture or myelogram may produce a throbbing frontal headache that worsens on standing.

Drugs. Many drugs can cause headaches. For example, indomethacin produces headaches — usually in the morning — in many patients. Vasodilators and drugs with a vasodilating effect, such as nitrates, typically cause a throbbing headache. Headaches may also follow withdrawal from vasopressors, such as caffeine, ergotamine, and sympathomimetics.

HERB ALERT

HERB ALERT

Herbal remedies — such as St. John's wort and ginseng — can cause various adverse reactions, including headaches.

Traction. Cervical traction with pins commonly causes a headache, which may be generalized or localized to pin insertion sites.

Special Considerations

Continue to monitor the patient’s vital signs and LOC. Watch for a change in the headache’s severity or location. To help ease the headache, administer an analgesic, darken the patient’s room, and minimize other stimuli. Explain the rationale of these interventions to the patient.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as skull X-rays, a computed tomography scan, lumbar puncture, or cerebral arteriography.

Patient Counseling

Explain the signs of reduced LOC and seizures that the patient or his caregivers should report. Explain ways to maintain a quiet environment and reduce environmental stress. Discuss the use of analgesics.

Pediatric Pointers

If a child is too young to describe his symptom, suspect a headache if you see him banging or holding his head. In an infant, a shrill cry or bulging fontanels may indicate increased ICP and a headache. In a school-age child, ask the parents about the child’s recent scholastic performance and about any problems at home that may produce a tension headache.

Twice as many young boys have migraine headaches as girls. In children older than age 3, a headache is the most common symptom of a brain tumor.

REFERENCES

Evers, S., & Jensen, R. (2011) . Treatment of medication overuse headache—Guideline of the EFNS headache panel. European

Journal of Neurology, 18, 1115–1121.

Lanteri-Minet, M., Duru, G., Mudge, M., & Cottrell, S. (2011). Quality of life impairment, disability and economic burden associated with chronic daily headache, focusing on chronic migraine with or without medication overuse: A systematic review . Cephalalgia, 31, 837–850.

Hearing Loss

Affecting nearly 16 million Americans, hearing loss may be temporary or permanent and partial or complete. This common symptom may involve reception of low-, middle-, or high-frequency tones. If the hearing loss doesn’t affect speech frequencies, the patient may be unaware of it.

Normally, sound waves enter the external auditory canal, and then travel to the middle ear’s tympanic membrane and ossicles (incus, malleus, and stapes) and into the inner ear’s cochlea. The cochlear division of cranial nerve (CN) VIII (auditory nerve) carries the sound impulse to the brain. This type of sound transmission, called air conduction, is normally better than bone conduction — sound transmission through bone to the inner ear.

Hearing loss can be classified as conductive, sensorineural, mixed, or functional. Conductive hearing loss results from external or middle ear disorders that block sound transmission. This type of hearing loss usually responds to medical or surgical intervention (or in some cases, both). Sensorineural hearing loss results from disorders of the inner ear or of CN VIII. Mixed hearing loss combines aspects of conductive and sensorineural hearing loss. Functional hearing loss results from psychological factors rather than identifiable organic damage.

Hearing loss may also result from trauma, infection, allergy, tumors, certain systemic and hereditary disorders, and the effects of ototoxic drugs and treatments. In most cases, however, it results from presbycusis, a type of sensorineural hearing loss that usually affects people older than age 50. Other physiologic causes of hearing loss include cerumen (earwax) impaction; barotitis media (unequal pressure on the eardrum) associated with descent in an airplane or elevator, diving, or close proximity to an explosion; and chronic exposure to noise over 90 decibels, which can occur on the job, with certain hobbies, or from listening to live or recorded music.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient reports hearing loss, ask him to describe it. Is it unilateral or bilateral? Continuous or intermittent? Ask about a family history of hearing loss. Then obtain the patient’s medical history, noting chronic ear infections, ear surgery, and ear or head trauma. Has the patient recently had an upper respiratory tract infection? After taking a drug history, have the patient describe his occupation and work environment.

Next, explore associated signs and symptoms. Does the patient have ear pain? If so, is it unilateral or bilateral, or continuous or intermittent? Ask the patient if he has noticed discharge from one or both ears. If so, have him describe its color and consistency, and note when it began. Does he hear ringing, buzzing, hissing, or other noises in one or both ears? If so, are the noises constant or intermittent? Does he experience dizziness? If so, when did he first notice it?

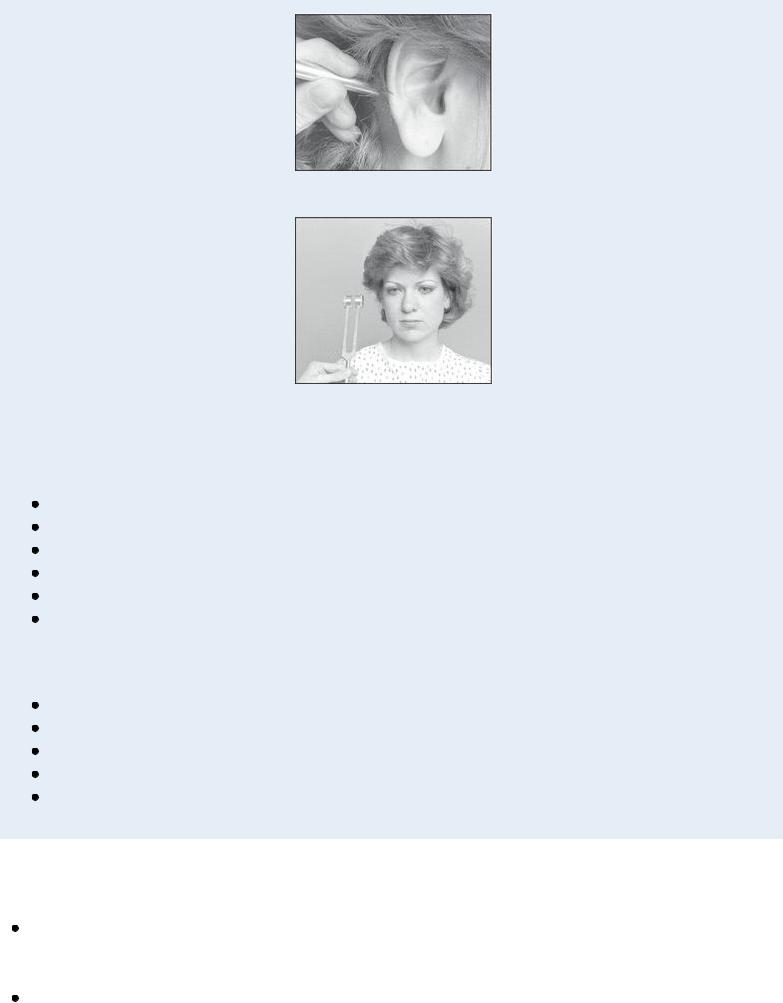

Begin the physical examination by inspecting the external ear for inflammation, boils, foreign bodies, and discharge. Then apply pressure to the tragus and mastoid to elicit tenderness. If you detect tenderness or external ear abnormalities, notify the physician to discuss whether an otoscopic examination should be done. (See Using an Otoscope Correctly, page 276.) During the otoscopic examination, note color change, perforation, bulging, or retraction of the tympanic membrane, which

normally looks like a shiny, pearl gray cone.

Next, evaluate the patient’s hearing acuity, using the ticking watch and whispered voice tests. Then perform Weber’s and the Rinne tests to obtain a preliminary evaluation of the type and degree of hearing loss. (See Differentiating Conductive from Sensorineural Hearing Loss, page 372.)

EXAMINATION TIP Differentiating Conductive from Sensorineural Hearing Loss

EXAMINATION TIP Differentiating Conductive from Sensorineural Hearing Loss

Weber’s and the Rinne tests can help determine whether the patient’s hearing loss is conductive or sensorineural. Weber’s test evaluates bone conduction; the Rinne test, bone and air conduction. Using a 512-Hz tuning fork, perform these preliminary tests as described here.

WEBER’S TEST

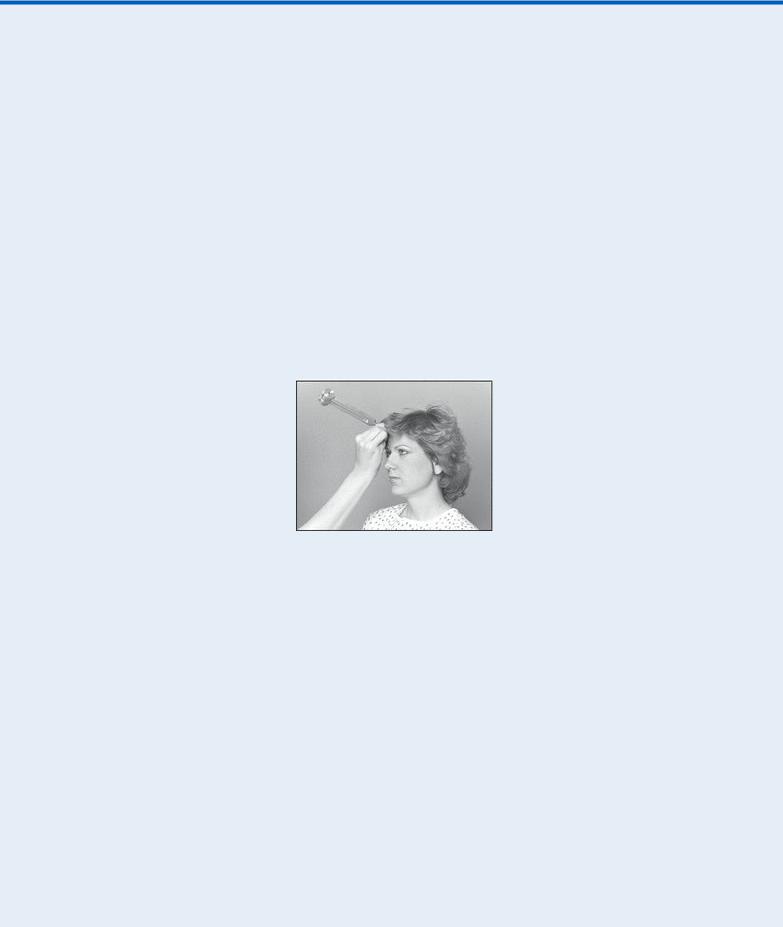

Place the base of a vibrating tuning fork firmly against the midline of the patient’s skull at the forehead. Ask her if she hears the tone equally well in both ears. If she does, Weber’s test is graded midline — a normal finding. In an abnormal Weber’s test (graded right or left), sound is louder in one ear, suggesting a conductive hearing loss in that ear or a sensorineural loss in the opposite ear.

RINNE TEST

Hold the base of a vibrating tuning fork against the patient's mastoid process to test bone conduction. Then quickly move the vibrating fork in front of her ear canal to test air conduction. Ask her to tell you which location has the louder or longer sound. Repeat the procedure for the other ear. In a positive Rinne test, air conduction lasts longer or sounds louder than bone conduction — a normal finding. In a negative test, the opposite is true: Bone conduction lasts longer or sounds louder than air conduction.

After performing both tests, correlate the results with other assessment data.

IMPLICATIONS OF RESULTS

Conductive hearing loss produces

Abnormal Weber’s test result

Negative Rinne test result

Improved hearing in noisy areas

Normal ability to discriminate sounds

Difficulty hearing when chewing

A quiet speaking voice

Sensorineural hearing loss produces

Positive Rinne test

Poor hearing in noisy areas

Difficulty hearing high-frequency sounds

Complaints that others mumble or shout

Tinnitus

Medical Causes

Acoustic neuroma. Acoustic neuroma, which is a CN VIII tumor, causes unilateral, progressive, sensorineural hearing loss. The patient may also develop tinnitus, vertigo, and — with cranial nerve compression — facial paralysis.

Adenoid hypertrophy. Eustachian tube dysfunction causes gradual conductive hearing loss accompanied by intermittent ear discharge. The patient also tends to breathe through his mouth

and may complain of a sensation of ear fullness.

Aural polyps. If a polyp occludes the external auditory canal, partial hearing loss may occur. The polyp typically bleeds easily and is covered by a purulent discharge.

Cholesteatoma. Gradual hearing loss is characteristic. It can be accompanied by vertigo and, at times, facial paralysis. Examination reveals eardrum perforation, pearly white balls in the ear canal, and possible discharge.

Cyst. Ear canal obstruction by a sebaceous or dermoid cyst causes progressive conductive hearing loss. On inspection, the cyst looks like a soft mass.

External ear canal tumor (malignant). Progressive conductive hearing loss is characteristic and is accompanied by deep, boring ear pain, purulent discharge and, eventually, facial paralysis. Examination may detect the granular, bleeding tumor.

Glomus jugulare tumor. Initially, this benign tumor causes mild, unilateral conductive hearing loss that becomes progressively more severe. The patient may report tinnitus that sounds like his heartbeat. Associated signs and symptoms include gradual congestion in the affected ear, throbbing or pulsating discomfort, bloody otorrhea, facial nerve paralysis, and vertigo. Although the tympanic membrane is normal, a reddened mass appears behind it.

Head trauma. Sudden conductive or sensorineural hearing loss may result from ossicle disruption, ear canal fracture, tympanic membrane perforation, or cochlear fracture associated with head trauma. Typically, the patient reports a headache and exhibits bleeding from his ear. Neurologic features vary and may include impaired vision and an altered level of consciousness. Ménière’s disease. Initially, Ménière’s disease, an inner ear disorder, produces intermittent, unilateral sensorineural hearing loss that involves only low tones. Later, hearing loss becomes constant and affects other tones. Associated signs and symptoms include intermittent severe vertigo, nausea and vomiting, a feeling of fullness in the ear, a roaring or hollow-seashell tinnitus, diaphoresis, and nystagmus.

Nasopharyngeal cancer. Nasopharyngeal cancer causes mild unilateral conductive hearing loss when it compresses the eustachian tube. Bone conduction is normal, and inspection reveals a retracted tympanic membrane backed by fluid. When this tumor obstructs the nasal airway, the patient may exhibit nasal speech and a bloody nasal and postnasal discharge. Cranial nerve involvement produces other findings, such as diplopia and rectus muscle paralysis.

Otitis externa. Conductive hearing loss resulting from debris in the ear canal characterizes acute and malignant otitis externa. With acute otitis externa, ear canal inflammation produces pain, itching, and a foul-smelling, sticky yellow discharge. Severe tenderness is typically elicited by chewing, opening the mouth, and pressing on the tragus or mastoid. The patient may also develop a low-grade fever, regional lymphadenopathy, a headache on the affected side, and mild to moderate pain around the ear that may later intensify. Examination may reveal greenish white debris or edema in the canal.

With malignant otitis externa, debris is also visible in the canal. This life-threatening disorder, which most commonly occurs in the patient with diabetes, causes sensorineural hearing loss, pruritus, tinnitus, and severe ear pain.

Otitis media. Otitis media is a middle ear inflammation that typically produces unilateral conductive hearing loss. In patients with acute suppurative otitis media, the hearing loss develops gradually over a few hours and is usually accompanied by an upper respiratory tract