Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

is heard at the apex, and doesn’t vary with inspiration. A left-sided S 4 can occur in hypertensive heart disease, coronary artery disease, aortic stenosis, and cardiomyopathy. It may also originate from right atrial contraction. A right-sided S4 is indicative of pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary stenosis. If so, it’s heard best at the lower left sternal border and intensifies with inspiration.

An atrial gallop seldom occurs in normal hearts; however, it may occur in elderly people and in athletes with physiologic hypertrophy of the left ventricle.

History and Physical Examination

When the patient’s condition permits, ask about a history of hypertension, angina, valvular stenosis, or cardiomyopathy. If appropriate, have him describe the frequency and severity of anginal attacks.

Medical Causes

Angina. An intermittent atrial gallop characteristically occurs during an anginal attack and disappears when angina subsides. This gallop may be accompanied by a paradoxical S2 or a new murmur. Typically, the patient complains of anginal chest pain — a feeling of tightness, pressure, achiness, or burning that can radiate from the retrosternal area to the neck, jaws, left shoulder, and arm. He may also exhibit dyspnea, tachycardia, palpitations, increased blood pressure, dizziness, diaphoresis, belching, nausea, and vomiting.

Aortic insufficiency (acute). Acute aortic insufficiency causes an atrial gallop accompanied by a soft, short diastolic murmur along the left sternal border. S2 may be soft or absent. Sometimes a soft, short midsystolic murmur may be heard over the second right intercostal space. Related cardiopulmonary findings may include tachycardia, S3, dyspnea, jugular vein distention, crackles, and, possibly, angina. The patient may also be fatigued and have cool extremities.

Aortic stenosis. Aortic stenosis usually causes an atrial gallop, especially when valvular obstruction is severe. Auscultation reveals a harsh, crescendo-decrescendo, systolic ejection murmur that’s loudest at the right sternal border near the second intercostal space. Dyspnea, anginal chest pain, and syncope are cardinal-associated findings. The patient may also display crackles, palpitations, fatigue, and diminished carotid pulses.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Suspect myocardial ischemia if you auscultate an atrial gallop in a patient with chest pain. (See Locating Heart Sounds. Also see Interpreting Heart Sounds, pages 348 and 349.) Take the patient’s vital signs and quickly assess for signs of heart failure, such as dyspnea, crackles, and jugular vein distention. If you detect these signs, connect the patient to a cardiac monitor and obtain an electrocardiogram (ECG). Administer an antianginal and oxygen. If the patient has dyspnea, elevate the head of the bed. Then auscultate for abnormal breath sounds. If you detect coarse crackles, ensure patent I.V. access and give oxygen and diuretics as needed. If the patient has bradycardia, he may require atropine and a pacemaker.

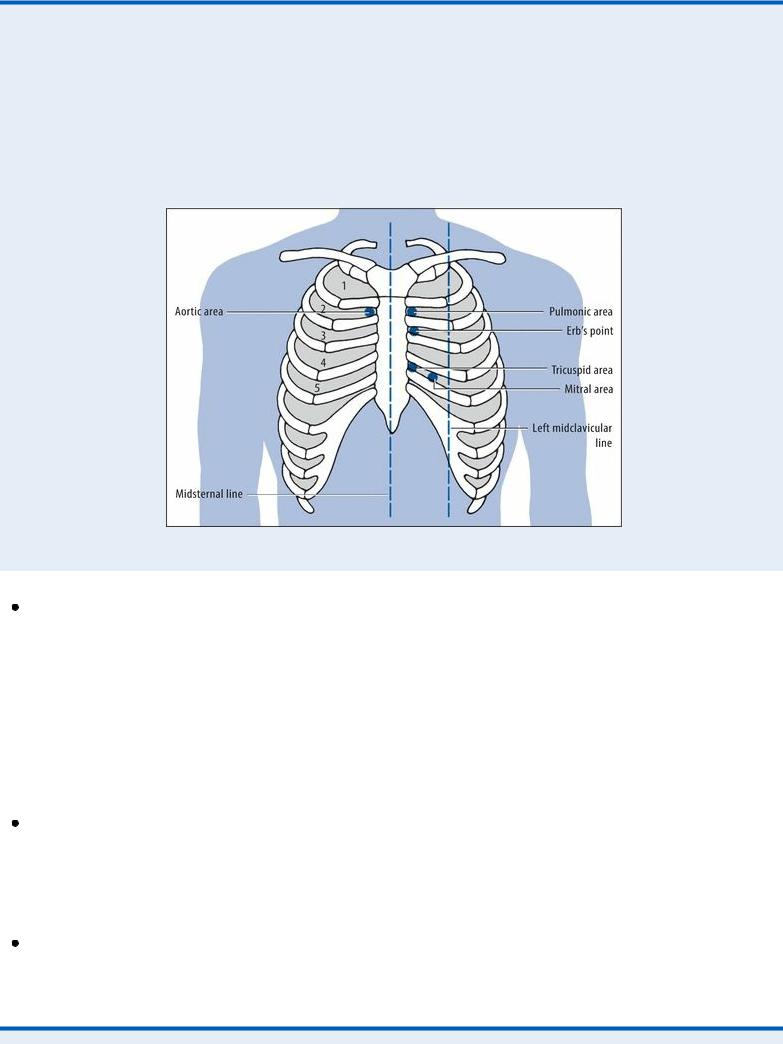

EXAMINATION TIP Locating Heart Sounds

EXAMINATION TIP Locating Heart Sounds

When auscultating heart sounds, remember that certain sounds are heard best in specific areas. Use the auscultatory points shown below to locate heart sounds quickly and accurately. Then expand your auscultation to nearby areas. Note that the numbers indicate pertinent intercostal spaces.

Atrioventricular (AV) block. First-degree AV block may cause an atrial gallop accompanied by a faint S1. Although the patient may have bradycardia, he’s usually asymptomatic. In seconddegree AV block, an atrial gallop is easily heard. If bradycardia develops, the patient may also experience hypotension, light-headedness, dizziness, and fatigue. An atrial gallop is also common in third-degree AV block. It varies in intensity with S 1 and is loudest when atrial systole coincides with early, rapid ventricular filling during diastole. The patient may be asymptomatic or have hypotension, light-headedness, dizziness, or syncope, depending on the ventricular rate. Bradycardia may also aggravate or provoke angina or symptoms of heart failure such as dyspnea.

Cardiomyopathy. An atrial gallop is a sign associated with cardiomyopathy, regardless of the type — dilated (most common), hypertrophic, or restrictive (least common). Additional findings may include dyspnea, orthopnea, crackles, fatigue, syncope, chest pain, palpitations, edema, jugular vein distention, S3, and transient or sustained bradycardia usually associated with tachycardia.

Hypertension. One of the earliest findings in systemic arterial hypertension is an atrial gallop. The patient may be asymptomatic, or he may experience a headache, weakness, epistaxis, tinnitus, dizziness, and fatigue.

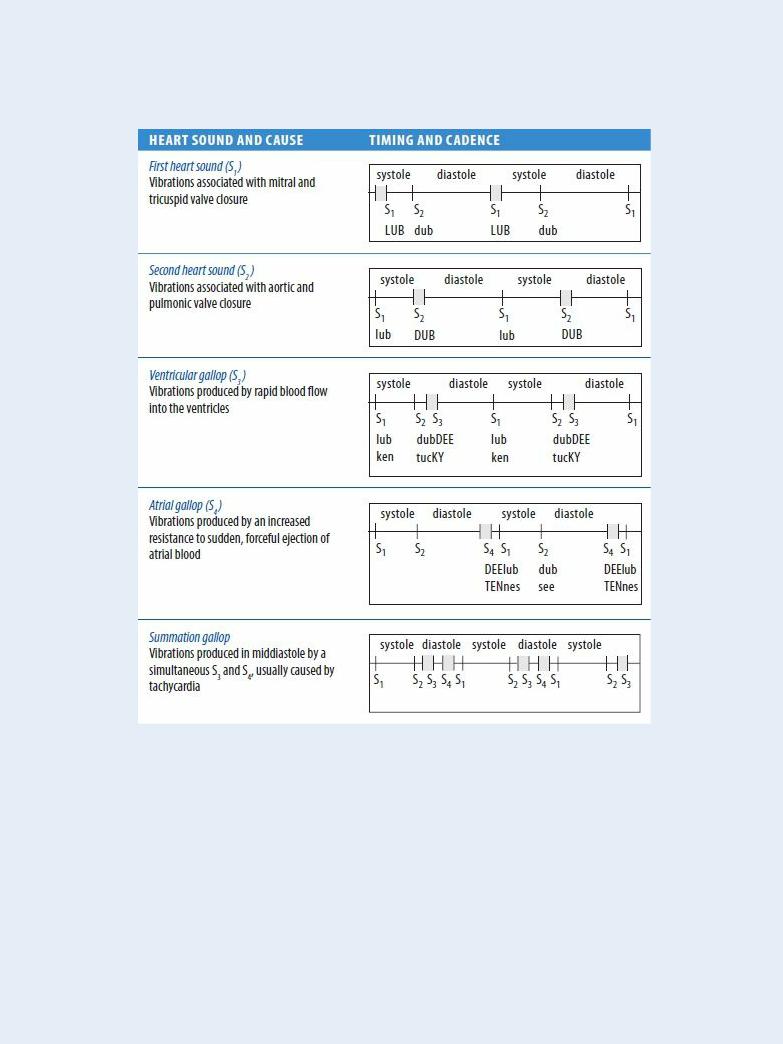

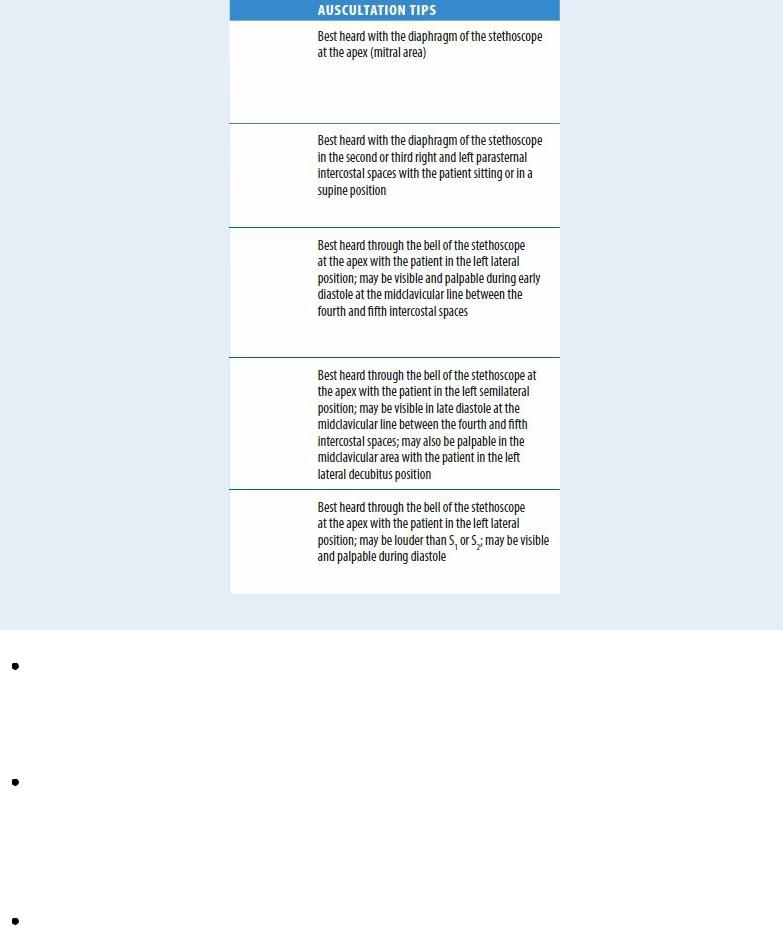

EXAMINATION TIP Interpreting Heart Sounds

EXAMINATION TIP Interpreting Heart Sounds

Detecting subtle variations in heart sounds requires concentration and practice. When you can recognize normal heart sounds, the abnormal sounds become more obvious.

Myocardial infarction (MI). An atrial gallop is a classic sign of a life-threatening MI; in fact, it may persist even after the infarction heals. Typically, the patient reports crushing substernal chest pain that may radiate to the back, neck, jaw, shoulder, and left arm. Associated signs and symptoms include dyspnea, restlessness, anxiety, a feeling of impending doom, diaphoresis, pallor, clammy skin, nausea, vomiting, and increased or decreased blood pressure.

Pulmonary embolism. Pulmonary embolism is a life-threatening disorder that causes a rightsided atrial gallop that’s usually heard along the lower left sternal border with a loud pulmonic closure sound. Other features include tachycardia, tachypnea, fever, chest pain, dyspnea, decreased breath sounds, crackles, a pleural chest rub, apprehension, diaphoresis, syncope, and cyanosis. The patient may have a productive cough with blood-tinged sputum or a nonproductive cough.

Thyrotoxicosis. An atrial gallop and an S3 may be auscultated in thyroid hormone overproduction. Other cardinal features include tachycardia, a bounding pulse, wide pulse pressure, palpitations, weight loss despite increased appetite, diarrhea, tremors, an enlarged thyroid, dyspnea, nervousness, difficulty concentrating, diaphoresis, heat intolerance, exophthalmos, weakness, fatigue, and muscle atrophy.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as an ECG, echocardiography, cardiac catheterization, such laboratory tests as CK-MB and troponin and, possibly, a lung scan.

Patient Counseling

Discuss with the patient ways to reduce his cardiac risk. Teach the patient the correct way to measure his pulse rate. Emphasize conditions that require medical attention. Stress the importance of followup appointments.

Pediatric Pointers

An atrial gallop may occur normally in children, especially after exercise. However, it may also result from congenital heart diseases, such as atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, and severe pulmonary valvular stenosis.

Geriatric Pointers

Because the absolute intensity of an atrial gallop doesn’t decrease with age, as it does with an S1, the relative intensity of S4 increases compared with S1. This explains the increased frequency of an audible S4 in elderly patients and why this sound may be considered a normal finding in older patients.

REFERENCES

Chen, J., Dharmarajan, K. , Wang, Y ., & Krumholz, H. M. (2013) . National trends in heart failure hospital stay rates, 2001 to 2009.

Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 61(10), 1078–1088.

Jhund, P. S. , Macintyre, K., Simpson, C. R., Lewsey, J. D., Stewart, S., Redpath, A., … McMurray, J. J. (2009). Long-term trends in first hospitalization for heart failure and subsequent survival between 1986 and 2003: A population study of 5.1 million people . Circulation, 119(4), 515–523.

Gallop, Ventricular

[S3]

A ventricular gallop is a heart sound (known as S3) associated with rapid ventricular filling in early diastole. Usually palpable, this low-frequency sound occurs about 0.15 second after the second heart sound (S2). It may originate in either the left or right ventricle. A right-sided gallop usually sounds louder on inspiration and is heard best along the lower left sternal border or over the xiphoid region. A left-sided gallop usually sounds louder on expiration and is heard best at the apex.

Ventricular gallops are easily overlooked because they’re usually faint. Fortunately, certain techniques make their detection more likely. These include auscultating in a quiet environment; examining the patient in the supine, left lateral, and semi-Fowler’s positions; and having the patient cough or raise his legs to augment the sound.

A physiologic ventricular gallop normally occurs in children and adults younger than age 40;

however, most people lose this third heart sound by age 40. This gallop may also occur during the third trimester of pregnancy. Abnormal S 3 (in adults older than age 40) can be a sign of decreased myocardial contractility, myocardial failure, and volume overload of the ventricle, as in mitral and tricuspid valve regurgitation. Although the physiologic S3 has the same timing as the pathologic S3, its intensity waxes and wanes with respiration. It’s also heard more faintly if the patient is sitting or standing.

A pathologic ventricular gallop may be one of the earliest signs of ventricular failure. It may result from one of two mechanisms: rapid deceleration of blood entering a stiff, noncompliant ventricle or rapid acceleration of blood associated with increased flow into the ventricle. A gallop that persists despite therapy indicates a poor prognosis.

Patients with cardiomyopathy or heart failure may develop a ventricular and an atrial gallop — a condition known as a summation gallop. (See Summation Gallop: Two Gallops in One.)

History and Physical Examination

After auscultating a ventricular gallop, focus your history and examination on the cardiovascular system. Begin the history by asking the patient if he has had chest pain. If so, have him describe its character, location, frequency, duration, and alleviating or aggravating factors. Also, ask about palpitations, dizziness, or syncope. Does the patient have difficulty breathing after exertion? While lying down? At rest? Does he have a cough? Ask about a history of cardiac disorders. Is the patient currently receiving treatment for heart failure? If so, which medications is he taking?

Summation Gallop: Two Gallops in One

When atrial and ventricular gallops occur simultaneously, they produce a short, low-pitched sound known as a summation gallop. This relatively uncommon sound occurs during middiastole (between S2 and S1) and is best heard with the bell of the stethoscope pressed lightly against the cardiac apex. It may be louder than either S1 or S2 and may cause visible apical movement during diastole.

CAUSES

A summation gallop may result from tachycardia or from delayed or blocked atrioventricular (AV) conduction. Tachycardia shortens ventricular filling time during diastole, causing it to coincide with atrial contraction. When the heart rate slows, the summation gallop is replaced by separate atrial and ventricular gallops, producing a quadruple rhythm much like the canter of a horse. Delayed AV conduction also brings atrial contraction closer to ventricular filling, creating a summation gallop.

A summation gallop usually results from heart failure or dilated congestive cardiomyopathy. It may also accompany other cardiac disorders. Occasionally, it signals further cardiac deterioration. For example, consider the hypertensive patient with a chronic atrial gallop who develops tachycardia and a superimposed ventricular gallop. If this patient abruptly displays a summation gallop, heart failure is the likely cause.

During the physical examination, carefully auscultate for murmurs or abnormalities in the first and

second heart sounds. Then listen for pulmonary crackles. Next, assess peripheral pulses, noting an alternating strong and weak pulse. Finally, palpate the liver to detect enlargement or tenderness, and assess for jugular vein distention and peripheral edema.

Medical Causes

Aortic insufficiency. Aortic insufficiency occurs secondary to reduced ejection fraction and elevated end-systolic volume. Acute and chronic aortic insufficiency may produce an S3. Typically, acute aortic insufficiency also causes an atrial gallop and a soft, short diastolic murmur over the left sternal border. S2 may be soft or absent. At times, a soft, short midsystolic murmur may be heard over the second right intercostal space. Related findings include tachycardia, dyspnea, jugular vein distention, and crackles.

Chronic aortic insufficiency produces a ventricular gallop and a high-pitched, blowing, decrescendo diastolic murmur that’s best heard over the second or third right intercostal space or the left sternal border. An Austin Flint murmur — an apical, rumbling, midto late-diastolic murmur — may also occur. Typical related findings include palpitations, tachycardia, anginal chest pain, fatigue, dyspnea, orthopnea, and crackles.

Cardiomyopathy. A ventricular gallop is characteristic in cardiomyopathy. When accompanied by an alternating pulse and altered S1 and S2, this gallop usually signals advanced heart disease. Other effects may include fatigue, dyspnea, orthopnea, chest pain, palpitations, syncope, crackles, peripheral edema, jugular vein distention, and an atrial gallop.

Heart failure. A cardinal sign of heart failure is a ventricular gallop. When it’s loud and accompanied by sinus tachycardia, this gallop may indicate severe heart failure. The patient with left-sided heart failure also exhibits fatigue, exertional dyspnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea and, possibly, a dry cough; with right-sided heart failure, jugular vein distention occurs. Other late features include tachypnea, chest tightness, palpitations, anorexia, nausea, dependent edema, weight gain, a slowed mental response, diaphoresis, pallor, hypotension, narrowed pulse pressure, and, possibly, oliguria. In some cases, inspiratory crackles, clubbing, and a tender, palpable liver may be present. As heart failure progresses, hemoptysis, cyanosis, severe pitting edema, and marked hepatomegaly may develop.

Mitral insufficiency. Acute and chronic mitral insufficiency may produce a ventricular gallop. In acute mitral insufficiency, auscultation may also reveal an early or holosystolic decrescendo murmur at the apex, an atrial gallop, and a widely split S2. Typically, the patient displays sinus tachycardia, tachypnea, orthopnea, dyspnea, crackles, jugular vein distention, and fatigue.

In chronic mitral insufficiency, a progressively severe ventricular gallop is typical. Auscultation also reveals a holosystolic, blowing, high-pitched apical murmur. The patient may report fatigue, exertional dyspnea, and palpitations, or he may be asymptomatic.

Thyrotoxicosis. Thyrotoxicosis may produce ventricular and atrial gallops, but its cardinal features are an enlarged thyroid gland, weight loss despite increased appetite, heat intolerance, diaphoresis, nervousness, tremors, tachycardia, palpitations, diarrhea, and dyspnea.

Special Considerations

Monitor the patient with a ventricular gallop; watch for and report tachycardia, dyspnea, crackles, and jugular vein distention. Give oxygen, diuretics, and other drugs, such as digoxin and angiotensin-

converting enzyme inhibitors, to prevent pulmonary edema.

Prepare the patient for electrocardiography, echocardiography, gated blood pool imaging, and cardiac catheterization.

Patient Counseling

Explain dietary and fluid restrictions the patient needs. Stress the importance of scheduled rest periods. Explain signs and symptoms of fluid overload that should be reported, and teach the patient how to monitor his daily weight.

Pediatric Pointers

A ventricular gallop is normally heard in children. However, it may accompany congenital abnormalities associated with heart failure, such as a large ventricular septal defect and patent ductus arteriosus. It may also result from sickle cell anemia. This gallop must be correlated with the patient’s associated signs and symptoms to be of diagnostic value.

REFERENCES

Go, A. S., Mozaffarian, D., Roger, V. L. , Benjamin, E. J., Berry, J. D., Borden, W. B. , … Turner, M. B. (2013) . Heart disease and stroke statistics—2013 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 127(1), e6–e245.

McMurray, J. J., Adamopoulos, S., Anker, S. D., Auricchio, A., Böhm, M., Dickstein, K., … Ponikowski, P. (2012). ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012 of the European society of cardiology developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. European Heart Journal, 33(14), 1787–1847.

Genital Lesions in the Male

Among the diverse lesions that may affect the male genitalia are warts, papules, ulcers, scales, and pustules. These common lesions may be painful or painless, singular or multiple. They may be limited to the genitalia or may also occur elsewhere on the body. (See Recognizing Common Male Genital Lesions, page 354.)

Genital lesions may result from infection, neoplasms, parasites, allergy, or the effects of drugs. These lesions can profoundly affect the patient’s self-image and relationships. In fact, the patient may hesitate to seek medical attention because he fears cancer or a sexually transmitted disease (STD).

Genital lesions that arise from an STD could mean that the patient is at risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Genital ulcers make HIV transmission between sexual partners more likely. Unfortunately, if the patient is treating himself, he may alter the lesions, making differential diagnosis especially difficult.

History and Physical Examination

Begin by asking the patient when he first noticed the lesion. Did it erupt after he began taking a new drug or after a trip out of the country? Has he had similar lesions before? If so, did he get medical treatment for them? Find out if he has been treating the lesion himself. If so, how? Does the lesion itch? If so, is the itching constant or does it bother him only at night? Note whether the lesion is painful. Ask for a description of any drainage from the lesions. Next, take a complete sexual history, noting the frequency of relations, number of sexual partners, and pattern of condom use.

Before you examine the patient, observe his clothing. Do his pants fit properly? Tight pants or underwear, especially those made of nonabsorbent fabrics, can promote the growth of bacteria and fungi. Examine the entire skin surface, noting the location, size, color, and pattern of the lesions. Do genital lesions resemble lesions on other parts of the body? Palpate for nodules, masses, and tenderness. Also, look for bleeding, edema, or signs of infection, such as purulent drainage or erythema. Finally, take the patient’s vital signs.

Medical Causes

Balanitis and balanoposthitis. Typically, balanitis (glans infection) and posthitis (prepuce infection) occur together (balanoposthitis), causing painful ulceration on the glans, foreskin, or penile shaft. Ulceration is usually preceded by 2 to 3 days of prepuce irritation and soreness, followed by a foul discharge and edema. The patient may then develop features of acute infection, such as a fever with chills, malaise, and dysuria. Without treatment, the ulcers may deepen and multiply. Eventually, the entire penis and scrotum may become gangrenous, resulting in life-threatening sepsis.

Bowen’s disease. Bowen’s disease is a painless, premalignant lesion that commonly occurs on the penis or scrotum but may also appear elsewhere. It appears as a brownish red, raised, scaly, indurated plaque with well-defined borders, which may ulcerate at its center.

Chancroid. Chancroid is an STD that’s characterized by the eruption of one or more lesions, usually on the groin, inner thigh, or penis. Within 24 hours, the lesion changes from a reddened area to a small papule. (A similar papule may erupt on the tongue, lip, breast, or umbilicus.) It then becomes an inflamed pustule that rapidly ulcerates. This painful — and usually deep — ulcer bleeds easily and commonly has a purulent gray or yellow exudate covering its base. Rarely more than 2 cm in diameter, it’s typically irregular in shape. The inguinal lymph nodes also enlarge, become very tender, and may drain pus.

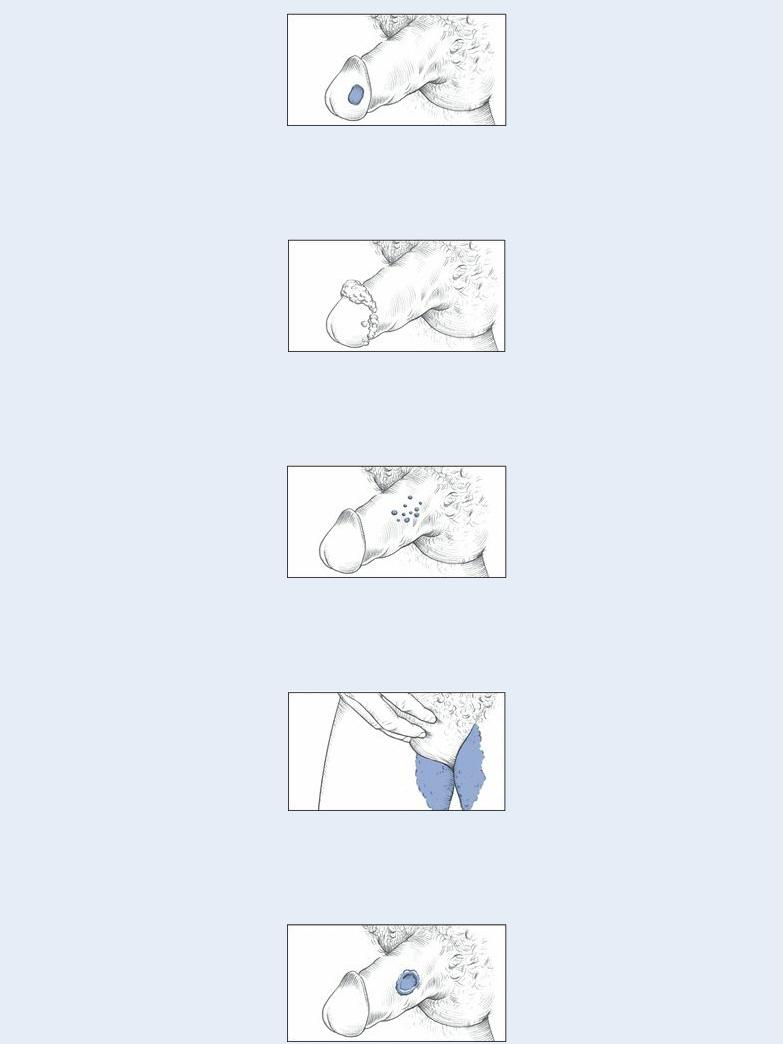

Recognizing Common Male Genital Lesions

Many lesions may affect the male genitalia. Some of the more common ones and their causes appear below.

Penile cancer causes a painless ulcerative lesion on the glans or foreskin, possibly accompanied by a foul-smelling discharge.

A fixed drug eruption causes a bright red to purplish lesion on the glans penis.

Genital warts are marked by clusters of flesh-colored papillary growths that may be barely visible or several inches in diameter.

Genital herpes begins as a swollen, slightly pruritic wheal and later becomes a group of small vesicles or blisters on the foreskin, glans, or penile shaft.

Tinea cruris (commonly known as jock itch) produces itchy patches of well-defined, slightly raised, scaly lesions that usually affect the inner thighs and groin.

Chancroid causes a painful ulcer that’s usually less than 2 cm in diameter and bleeds easily. The lesion may be deep and covered by a gray or yellow exudate at its base.