Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

Propulsive gait is a cardinal sign of advanced Parkinson’s disease; it results from progressive degeneration of the ganglia, which are primarily responsible for smooth muscle movement. Because this sign develops gradually and its accompanying effects are usually wrongly attributed to aging, propulsive gait commonly goes unnoticed or unreported until severe disability results.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient when his gait impairment first developed and whether it has recently worsened.

Because he may have difficulty remembering, having attributed the gait to “old age” or disease processes, you may be able to gain information from family members or friends, especially those who see the patient only sporadically.

Also, obtain a thorough drug history, including medication type and dosage. Ask the patient if he has been taking tranquilizers, especially phenothiazines. If he knows he has Parkinson’s disease and has been taking levodopa, pay particular attention to the dosage because an overdose can cause an acute exacerbation of signs and symptoms. If Parkinson’s disease isn’t a known or suspected diagnosis, ask the patient if he has been acutely or routinely exposed to carbon monoxide or manganese.

Begin the physical examination by testing the patient’s reflexes and sensorimotor function, noting abnormal response patterns.

Medical Causes

Parkinson’s disease. The characteristic and permanent propulsive gait begins early as a shuffle. As the disease progresses, the gait slows. Cardinal signs of the disease are progressive muscle rigidity, which may be uniform (lead-pipe rigidity) or jerky (cogwheel rigidity); akinesia; and an insidious tremor that begins in the fingers, increases during stress or anxiety, and decreases with purposeful movement and sleep. Besides the gait, akinesia also typically produces a monotone voice, drooling, masklike facies, a stooped posture, and dysarthria, dysphagia, or both. Occasionally, it also causes oculogyric crises or blepharospasm.

Other Causes

Drugs. Propulsive gait and possibly other extrapyramidal effects can result from the use of phenothiazines, other antipsychotics (notably haloperidol, thiothixene, and loxapine) and, infrequently, metoclopramide and metyrosine. Such effects are usually temporary, disappearing within a few weeks after therapy is discontinued.

Carbon monoxide poisoning. A propulsive gait commonly appears several weeks after acute carbon monoxide intoxication. Earlier effects include muscle rigidity, choreoathetoid movements, generalized seizures, myoclonic jerks, masklike facies, and dementia.

Manganese poisoning. Chronic overexposure to manganese can cause an insidious, usually permanent, propulsive gait. Typical early findings include fatigue, muscle weakness and rigidity, dystonia, resting tremor, choreoathetoid movements, masklike facies, and personality changes. Those at risk for manganese poisoning are welders, railroad workers, miners, steelworkers, and workers who handle pesticides.

Special Considerations

Because of his gait and associated motor impairment, the patient may have problems performing activities of daily living. Assist him as appropriate, while at the same time encouraging his independence, self-reliance, and confidence. Advise the patient and his family to allow plenty of time for these activities, especially walking, because he’s particularly susceptible to falls due to festination and poor balance. Encourage the patient to maintain ambulation; for safety reasons, remember to stay with him while he’s walking, especially if he’s on unfamiliar or uneven ground.

You may need to refer him to a physical therapist for exercise therapy and gait retraining.

Patient Counseling

Advise the patient and his family to allow plenty of time for walking to avoid falls. Instruct the patient on the use of assistive devices, if appropriate.

Pediatric Pointers

Propulsive gait, usually with severe tremors, typically occurs in juvenile parkinsonism, a rare form. Other possible but rare causes include Hallervorden-Spatz disease and kernicterus.

REFERENCES

Dean, C. M., Ada, L., Bampton, J., Morris, M. E., Katrak P. H. , & Potts, S. (2010). Treadmill walking with body weight support in sub acute non-ambulatory stroke improves walking capacity more than overground walking: A randomised trial. Journal of Geophysics Research, 56(2), 97–103.

Yen, S. C. , Schmit, B. D., Landry, J. M., Roth, H., & Wu, M. (2012) . Locomotor adaptation to resistance during treadmill training transfers to overground walking in human. Experimental Brain Research, 216(3), 473–482.

Gait, Scissors

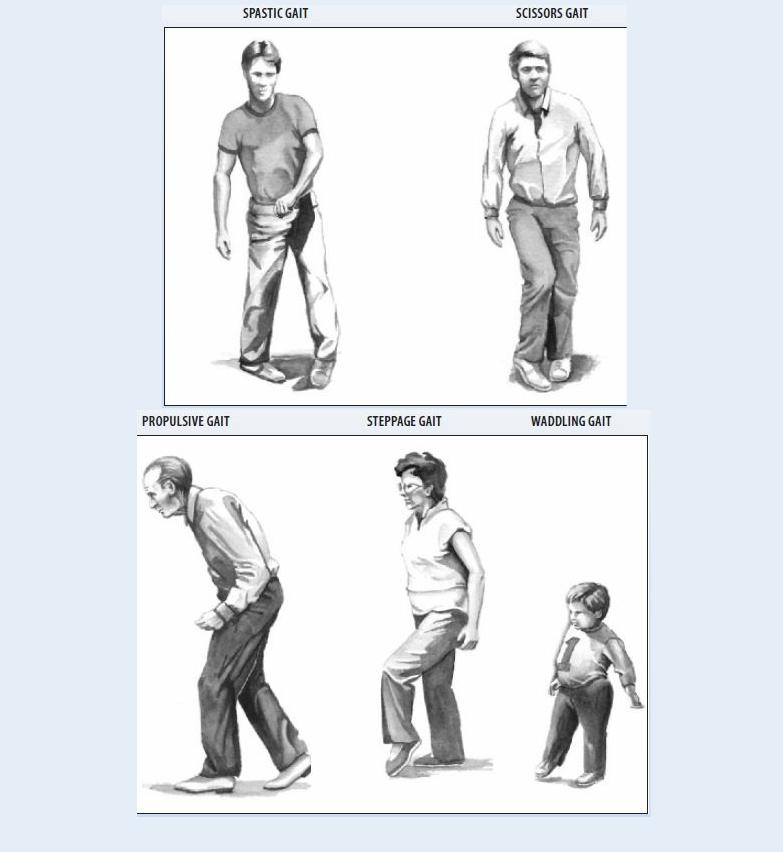

Resulting from bilateral spastic paresis (diplegia), scissors gait affects both legs and has little or no effect on the arms. The patient’s legs flex slightly at the hips and knees, so he looks as if he’s crouching. With each step, his thighs adduct and his knees hit or cross in a scissors-like movement. (See Identifying Gait Abnormalities, pages 336 and 337.) His steps are short, regular, and laborious, as if he were wading through waist-deep water. His feet may be plantar flexed and turned inward, with a shortened Achilles tendon; as a result, he walks on his toes or on the balls of his feet and may scrape his toes on the ground.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient (or a family member, if the patient can’t answer) about the onset and duration of the gait. Has it progressively worsened or remained constant? Ask about a history of trauma, including birth trauma, and neurologic disorders. Thoroughly evaluate motor and sensory function and deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) in the legs.

Medical Causes

Cerebral palsy. In the spastic form of cerebral palsy, patients walk on their toes with a scissors gait. Other features include hyperactive DTRs, increased stretch reflexes, rapid alternating muscle contraction and relaxation, muscle weakness, underdevelopment of affected limbs, and a tendency toward contractures.

Cervical spondylosis with myelopathy. Scissors gait develops in the late stages of cervical spondylosis with myelopathy and steadily worsens. Related findings mimic those of a herniated disk: severe low back pain, which may radiate to the buttocks, legs, and feet; muscle spasms; sensorimotor loss; and muscle weakness and atrophy.

Multiple sclerosis. Progressive scissors gait usually develops gradually, with infrequent

remissions. Characteristic muscle weakness, usually in the legs, ranges from minor fatigability to paraparesis with urinary urgency and constipation. Related findings include facial pain, vision disturbances, paresthesia, incoordination, and loss of proprioception and vibration sensation in the ankle and toes.

Spinal cord tumor. Scissors gait can develop gradually from a thoracic or lumbar tumor. Other findings reflect the location of the tumor and may include radicular, subscapular, shoulder, groin, leg, or flank pain; muscle spasms or fasciculations; muscle atrophy; sensory deficits, such as paresthesia and a girdle sensation of the abdomen and chest; hyperactive DTRs; a bilateral Babinski’s reflex; spastic neurogenic bladder; and sexual dysfunction.

Syringomyelia. Scissors gait usually occurs late in syringomyelia, along with analgesia and thermanesthesia, muscle atrophy and weakness, and Charcot’s joints. Other effects may include the loss of fingernails, fingers, or toes; Dupuytren’s contracture of the palms; scoliosis; and clubfoot. Skin in the affected areas is commonly dry, scaly, and grooved.

Special Considerations

Because of the sensory loss associated with scissors gait, provide meticulous skin care to prevent skin breakdown and pressure ulcer formation. Also, give the patient and his family complete skin care instructions. If appropriate, provide bladder and bowel retraining.

Provide daily active and passive range-of-motion exercises. Referral to a physical therapist may be required for gait retraining and for possible in-shoe splints or leg braces to maintain proper foot alignment for standing and walking.

Patient Counseling

Advise the patient and his family on complete skin care. Teach them about bladder and bowel retraining, if appropriate. Reinforce the proper use of splints or braces, if appropriate.

Pediatric Pointers

The major causes of scissors gait in children are cerebral palsy, hereditary spastic paraplegia, and spinal injury at birth. If spastic paraplegia is present at birth, scissors gait becomes apparent when the child begins to walk, which is usually later than normal.

REFERENCES

Callisaya, M. L., Blizzard, L., Schmidt, M. D., McGinley, J. L., & Srikanth, V. K. (2010). Ageing and gait variability—a population-based study of older people. Age Ageing, 39(2), 191–197.

De Laat, K. F., van Norden, A. G., Gons, R. A., van Oudheusden, L. J., van Uden, I. W., Bloem, B. R., … de Leeuw, F. E. (2010). Gait in elderly with cerebral small vessel disease. Stroke, 41(8), 1652–1658.

Gait, Spastic

[Hemiplegic gait]

Spastic gait — sometimes referred to as paretic or weak gait—is a stiff, foot-dragging walk caused by unilateral leg muscle hypertonicity. This gait indicates focal damage to the corticospinal

tract. The affected leg becomes rigid, with a marked decrease in flexion at the hip and knee and possibly plantar flexion and equinovarus deformity of the foot. Because the patient’s leg doesn’t swing normally at the hip or knee, his foot tends to drag or shuffle, scraping his toes on the ground. (See Identifying Gait Abnormalities, pages 336 and 337.) To compensate, the pelvis of the affected side tilts upward in an attempt to lift the toes, causing the patient’s leg to abduct and circumduct. Also, arm swing is hindered on the same side as the affected leg.

Spastic gait usually develops after a period of flaccidity (hypotonicity) in the affected leg. Whatever the cause, the gait is usually permanent after it develops.

History and Physical Examination

Find out when the patient first noticed the gait impairment and whether it developed suddenly or gradually. Ask him if it waxes and wanes, or if it has worsened progressively. Does fatigue, hot weather, or warm baths or showers worsen the gait? Such exacerbation typically occurs in multiple sclerosis. Focus your medical history questions on neurologic disorders, recent head trauma, and degenerative diseases.

During the physical examination, test and compare strength, range of motion (ROM), and sensory function in all limbs. Also, observe and palpate for muscle flaccidity or atrophy.

Medical Causes

Brain abscess. In brain abscess, spastic gait generally develops slowly after a period of muscle flaccidity and fever. Early signs and symptoms of abscess reflect increased intracranial pressure (ICP): a headache, nausea, vomiting, and focal or generalized seizures. Later, site-specific features may include hemiparesis, tremors, visual disturbances, nystagmus, and pupillary inequality. The patient’s level of consciousness may range from drowsiness to stupor.

Brain tumor. Depending on the site and type of tumor, spastic gait usually develops gradually and worsens over time. Accompanying effects may include signs of increased ICP (a headache, nausea, vomiting, and focal or generalized seizures), papilledema, sensory loss on the affected side, dysarthria, ocular palsies, aphasia, and personality changes.

Head trauma. Spastic gait typically follows the acute stage of head trauma. The patient may also experience focal or generalized seizures, personality changes, a headache, and focal neurologic signs, such as aphasia and visual field deficits.

Multiple sclerosis. Spastic gait begins insidiously and follows multiple sclerosis’ characteristic cycle of remission and exacerbation. The gait, as well as other signs and symptoms, commonly worsens in warm weather or after a warm bath or shower. Characteristic weakness, usually affecting the legs, ranges from minor fatigability to paraparesis with urinary urgency and constipation. Other effects include facial pain, paresthesia, incoordination, loss of proprioception and vibration sensation in the ankle and toes, and vision disturbances.

Stroke. Spastic gait usually appears after a period of muscle weakness and hypotonicity on the affected side. Associated effects may include unilateral muscle atrophy, sensory loss, and footdrop; aphasia; dysarthria; dysphagia; visual field deficits; diplopia; and ocular palsies.

Special Considerations

Because leg muscle contractures are commonly associated with spastic gait, promote daily exercise

and active and passive ROM exercises. The patient may have poor balance and a tendency to fall to the paralyzed side, so stay with him while he’s walking. Provide a cane or a walker, as indicated. As appropriate, refer the patient to a physical therapist for gait retraining and possible in-shoe splints or leg braces to maintain proper foot alignment for standing and walking.

Patient Counseling

Reinforce the importance of ambulating with assistance. Teach the patient to use a cane or a walker, as indicated.

Pediatric Pointers

Causes of spastic gait in children include sickle cell crisis, cerebral palsy, porencephalic cysts, and arteriovenous malformation that causes hemorrhage or ischemia.

REFERENCES

Ahmari, S. E., Spellman, T., Douglass, N. L., Kheirbek, M. A., Simpson, H. B., Deisseroth, K., … Hen, R. (2013) . Repeated corticostriatal stimulation generates persistent OCD-like behavior. Science, 340, 1234–1239.

Air, E. L., Ostrem, J. L., Sanger, T. D. , & Starr, P. A. (2011) . Deep brain stimulation in children: Experience and technical pearls.

Journal of Neurosurgical Pediatrics, 8, 566–574.

Gait, Steppage

[Equine gait, paretic gait, prancing gait, weak gait]

Steppage gait typically results from footdrop caused by weakness or paralysis of pretibial and peroneal muscles, usually from lower motor neuron lesions. Footdrop causes the foot to hang with the toes pointing down, causing the toes to scrape the ground during ambulation. To compensate, the hip rotates outward and the hip and knee flex in an exaggerated fashion to lift the advancing leg off the ground. The foot is thrown forward, and the toes hit the ground first, producing an audible slap. (See Identifying Gait Abnormalities, pages 336 and 337.) The rhythm of the gait is usually regular, with even steps and normal upper body posture and arm swing. Steppage gait can be unilateral or bilateral and permanent or transient, depending on the site and type of neural damage.

History and Physical Examination

Begin by asking the patient about the onset of the gait and recent changes in its character. Does a family member have a similar gait? Find out if the patient has had a traumatic injury to the buttocks, hips, legs, or knees. Ask about a history of chronic disorders that may be associated with polyneuropathy, such as diabetes mellitus, polyarteritis nodosa, and alcoholism. While you’re taking the history, observe whether the patient crosses his legs while sitting because this may put pressure on the peroneal nerve.

Inspect and palpate the patient’s calves and feet for muscle atrophy and wasting. Using a pin, test for sensory deficits along the entire length of both legs.

Medical Causes

Guillain-Barré syndrome. Typically occurring after recovery from the acute stage of GuillainBarré syndrome, steppage gait can be mild or severe and unilateral or bilateral; it’s invariably permanent. Muscle weakness usually begins in the legs, extends to the arms and face within 72 hours, and can progress to total motor paralysis and respiratory failure. Other effects include footdrop, transient paresthesia, hypernasality, dysphagia, diaphoresis, tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension, and incontinence.

Herniated lumbar disk. Unilateral steppage gait and footdrop commonly occur with late-stage weakness and atrophy of leg muscles. However, the most pronounced symptom is severe low back pain, which may radiate to the buttocks, legs, and feet, usually unilaterally. Sciatic pain follows, often accompanied by muscle spasms and sensorimotor loss. Paresthesia and fasciculations may occur.

Multiple sclerosis. Steppage gait and footdrop typically fluctuate in severity with multiple sclerosis’ characteristic cycle of periodic exacerbation and remission. Muscle weakness, usually affecting the legs, can range from minor fatigability to paraparesis with urinary urgency and constipation. Related findings include facial pain, visual disturbances, paresthesia, incoordination, and sensory loss in the ankle and toes.

Peroneal muscle atrophy. Bilateral steppage gait and footdrop begin insidiously in peroneal muscle atrophy. Foot, peroneal, and ankle dorsiflexor muscles are affected first. Other early signs and symptoms include paresthesia, aching, and cramping in the feet and legs along with coldness, swelling, and cyanosis. As the disorder progresses, all leg muscles become weak and atrophic, with hypoactive or absent deep tendon reflexes (DTRs). Later, atrophy and sensory losses spread to the hands and arms.

Peroneal nerve trauma. Temporary ipsilateral steppage gait occurs suddenly but resolves with the release of peroneal nerve pressure. The gait is associated with footdrop and muscle weakness and sensory loss over the lateral surface of the calf and foot.

Special Considerations

The patient with steppage gait may tire rapidly when walking because of the extra effort he must expend to lift his feet off the ground. When he tires, he may stub his toes, causing a fall. To prevent this, help the patient recognize his exercise limits and encourage him to get adequate rest. Refer him to a physical therapist, if appropriate, for gait retraining and possible application of in-shoe splints or leg braces to maintain correct foot alignment.

Patient Counseling

Help the patient to recognize his exercise limits and encourage him to get adequate rest. Teach the patient how to use splints and braces.

REFERENCES

Kallmes, D. F., Comstock, B. A., Heagerty, P. J. , Turner, J. A. , Wilson, D. J., Diamond, T. H., … Jarvik J. G. (2009). A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal fractures. New England Journal of Medicine, 361, 569–579.

Kumar, G., Goyal, M. K., Lucchese, S., & Dhand, U. (2011). Copper deficiency myelopathy can also involve the brain stem. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 32, 14–15.

Gait, Waddling

Waddling gait, a distinctive ducklike walk, is an important sign of muscular dystrophy, spinal muscle atrophy or, rarely, congenital hip displacement. It may be present when the child begins to walk or may appear only later in life. The gait results from deterioration of the pelvic girdle muscles — primarily the gluteus medius, hip flexors, and hip extensors. Weakness in these muscles hinders stabilization of the weight-bearing hip during walking, causing the opposite hip to drop and the trunk to lean toward that side in an attempt to maintain balance. (See Identifying Gait Abnormalities, pages 336 and 337.)

Typically, the legs assume a wide stance, and the trunk is thrown back to further improve stability, exaggerating lordosis, and abdominal protrusion. In severe cases, leg and foot muscle contractures may cause equinovarus deformity of the foot combined with circumduction or bowing of the legs.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient (or a family member, if the patient is a young child) when the gait first appeared and if it has recently worsened. To determine the extent of pelvic girdle and leg muscle weakness, ask if the patient falls frequently or has difficulty climbing stairs, rising from a chair, or walking. Also, find out if he was late in learning to walk or holding his head upright. Obtain a family history, focusing on problems of muscle weakness and gait and on congenital motor disorders.

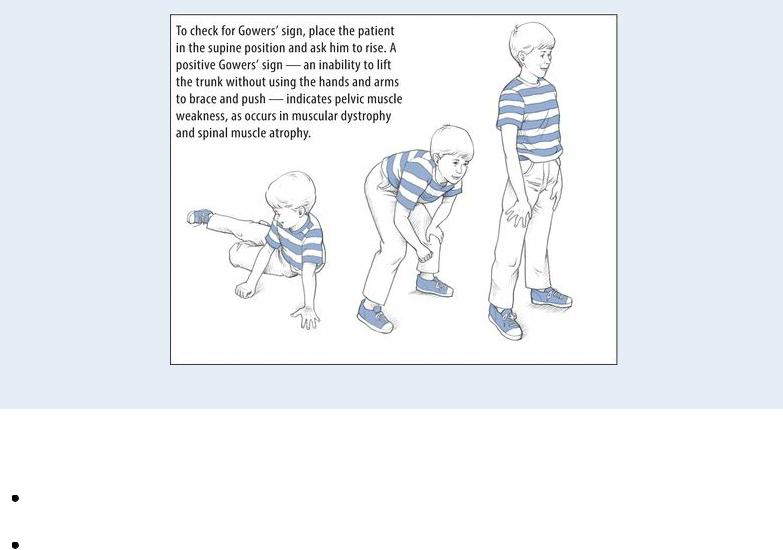

Inspect and palpate leg muscles, especially the calves, for size and tone. Check for a positive Gowers’ sign, which indicates pelvic muscle weakness. (See Identifying Gowers’ Sign .) Next, assess motor strength and function in the shoulders, arms, and hands, looking for weakness or asymmetrical movements.

EXAMINATION TIP Identifying Gowers’ Sign

EXAMINATION TIP Identifying Gowers’ Sign

To check for Gowers’ sign, place the patient in the supine position and ask him to rise. A positive Gowers’ sign — an inability to lift the trunk without using the hands and arms to brace and push — indicates pelvic muscle weakness, as occurs in muscular dystrophy and spinal muscle atrophy.

Medical Causes

Congenital hip dysplasia. Bilateral hip dislocation produces a waddling gait with lordosis and pain.

Muscular dystrophy. With Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy, waddling gait becomes clinically evident between ages 3 and 5. The gait worsens as the disease progresses, until the child loses the ability to walk and requires the use of a wheelchair, usually between ages 10 and 12. Early signs are usually subtle: a delay in learning to walk, frequent falls, gait or posture abnormalities, and intermittent calf pain. Common later findings include lordosis with abdominal protrusion, a positive Gowers’ sign, and equinovarus foot position. As the disease progresses, its effects become more prominent; they commonly include rapid muscle wasting beginning in the legs and spreading to the arms (although calf and upper arm muscles may become hypertrophied, firm, and rubbery), muscle contractures, limited dorsiflexion of the feet and extension of the knees and elbows, obesity and, possibly, mild mental retardation. Serious complications result when kyphoscoliosis develops, leading to respiratory dysfunction and, eventually, death from cardiac or respiratory failure.

With Becker’s muscular dystrophy, waddling gait typically becomes apparent in late adolescence, slowly worsens during the third decade, and culminates in total loss of ambulation. Muscle weakness first appears in the pelvic and upper arm muscles. Progressive wasting with selected muscle hypertrophy produces lordosis with abdominal protrusion, poor balance, a positive Gowers’ sign and, possibly, mental retardation.

With facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, which usually occurs late in childhood and during adolescence, waddling gait appears after muscle wasting has spread downward from the face and shoulder girdle to the pelvic girdle and legs. Earlier effects include progressive weakness and atrophy of facial, shoulder, and arm muscles; slight lordosis; and pelvic instability.

Spinal muscle atrophy. With Kugelberg-Welander syndrome, waddling gait occurs early (usually after age 2) and typically progresses slowly, culminating in the total loss of ambulation up to 20 years later. Related findings may include muscle atrophy in the legs and pelvis, progressing to the shoulders; a positive Gowers’ sign; ophthalmoplegia; and tongue fasciculations.

With Werdnig-Hoffmann disease, waddling gait typically begins when the child learns to walk. Reflexes may be absent. The gait progressively worsens, culminating in complete loss of ambulation by adolescence. Associated findings include lordosis with abdominal protrusion and muscle weakness in the hips and thighs.

Special Considerations

Although there’s no cure for this gait, daily passive and active muscle-stretching exercises should be performed for arms and legs. If possible, have the patient walk at least 3 hours each day (with leg braces, if necessary) to maintain muscle strength, reduce contractures, and delay further gait deterioration. Stay near the patient during the walk, especially if he’s on unfamiliar or uneven ground. Provide a balanced diet to maintain energy levels and prevent obesity. Because of the grim prognosis associated with muscular dystrophy and spinal muscle atrophy, provide emotional support for the patient and his family.

Patient Counseling

Caution the patient about long, unbroken periods of bed rest, which accelerate muscle deterioration. Refer the patient to a local Muscular Dystrophy Association chapter, as indicated. Suggest genetic counseling for parents, if they’re considering having more children.

REFERENCES

Huang, Y., Meijer, O. G., Lin, J., Bruijn, S. M., Wu, W., Lin, X., … van Dieën, J. H. (2010) . The effects of stride length and stride frequency on trunk coordination in human walking. Gait Posture, 31, 444–449.

Hurt, C. P. , Rosenblatt, N., Crenshaw, J. R., & Grabiner, M. D. (2010). Variation in trunk kinematics influences variation in step width during treadmill walking by older and younger adults. Gait Posture, 31, 461–464.

Gallop, Atrial

[S4]

An atrial or presystolic gallop is an extra heart sound (known as S4) that’s heard or typically palpated immediately before the first heart sound (S1), late in diastole. This low-pitched sound is heard best with the bell of the stethoscope pressed lightly against the cardiac apex. Some clinicians say that an S4 has the cadence of the “Ten” in Tennessee (Ten = S4; nes = Sl; see = S2).

This gallop typically results from hypertension, conduction defects, valvular disorders, or other problems such as ischemia. Occasionally, it helps differentiate angina from other causes of chest pain. It results from abnormal forceful atrial contraction caused by augmented ventricular filling or by decreased left ventricular compliance. An atrial gallop usually originates from left atrial contraction,