- •Contents

- •Preface

- •1.1 Elementary thermodynamic ideas of surfaces

- •1.1.1 Thermodynamic potentials and the dividing surface

- •1.1.2 Surface tension and surface energy

- •1.1.3 Surface energy and surface stress

- •1.2 Surface energies and the Wulff theorem

- •1.2.1 General considerations

- •1.2.3 Wulff construction and the forms of small crystals

- •1.3 Thermodynamics versus kinetics

- •1.3.1 Thermodynamics of the vapor pressure

- •1.3.2 The kinetics of crystal growth

- •1.4 Introduction to surface and adsorbate reconstructions

- •1.4.1 Overview

- •1.4.2 General comments and notation

- •1.4.7 Polar semiconductors, such as GaAs(111)

- •1.5 Introduction to surface electronics

- •1.5.3 Surface states and related ideas

- •1.5.4 Surface Brillouin zone

- •1.5.5 Band bending, due to surface states

- •1.5.6 The image force

- •1.5.7 Screening

- •Further reading for chapter 1

- •Problems for chapter 1

- •2.1 Kinetic theory concepts

- •2.1.1 Arrival rate of atoms at a surface

- •2.1.2 The molecular density, n

- •2.2 Vacuum concepts

- •2.2.1 System volumes, leak rates and pumping speeds

- •2.2.2 The idea of conductance

- •2.2.3 Measurement of system pressure

- •2.3 UHV hardware: pumps, tubes, materials and pressure measurement

- •2.3.1 Introduction: sources of information

- •2.3.2 Types of pump

- •2.3.4 Choice of materials

- •2.3.5 Pressure measurement and gas composition

- •2.4.1 Cleaning and sample preparation

- •2.4.3 Sample transfer devices

- •2.4.4 From laboratory experiments to production processes

- •2.5.1 Historical descriptions and recent compilations

- •2.5.2 Thermal evaporation and the uniformity of deposits

- •2.5.3 Molecular beam epitaxy and related methods

- •2.5.4 Sputtering and ion beam assisted deposition

- •2.5.5 Chemical vapor deposition techniques

- •Further reading for chapter 2

- •Problems for chapter 2

- •3.1.1 Surface techniques as scattering experiments

- •3.1.2 Reasons for surface sensitivity

- •3.1.3 Microscopic examination of surfaces

- •3.1.4 Acronyms

- •3.2.1 LEED

- •3.2.2 RHEED and THEED

- •3.3 Inelastic scattering techniques: chemical and electronic state information

- •3.3.1 Electron spectroscopic techniques

- •3.3.2 Photoelectron spectroscopies: XPS and UPS

- •3.3.3 Auger electron spectroscopy: energies and atomic physics

- •3.3.4 AES, XPS and UPS in solids and at surfaces

- •3.4.2 Ratio techniques

- •3.5.1 Scanning electron and Auger microscopy

- •3.5.3 Towards the highest spatial resolution: (a) SEM/STEM

- •Further reading for chapter 3

- •Problems, talks and projects for chapter 3

- •4.2 Statistical physics of adsorption at low coverage

- •4.2.1 General points

- •4.2.2 Localized adsorption: the Langmuir adsorption isotherm

- •4.2.4 Interactions and vibrations in higher density adsorbates

- •4.3 Phase diagrams and phase transitions

- •4.3.1 Adsorption in equilibrium with the gas phase

- •4.3.2 Adsorption out of equilibrium with the gas phase

- •4.4 Physisorption: interatomic forces and lattice dynamical models

- •4.4.1 Thermodynamic information from single surface techniques

- •4.4.2 The crystallography of monolayer solids

- •4.4.3 Melting in two dimensions

- •4.4.4 Construction and understanding of phase diagrams

- •4.5 Chemisorption: quantum mechanical models and chemical practice

- •4.5.1 Phases and phase transitions of the lattice gas

- •4.5.4 Chemisorption and catalysis: macroeconomics, macromolecules and microscopy

- •Further reading for chapter 4

- •Problems and projects for chapter 4

- •5.1 Introduction: growth modes and nucleation barriers

- •5.1.1 Why are we studying epitaxial growth?

- •5.1.3 Growth modes and adsorption isotherms

- •5.1.4 Nucleation barriers in classical and atomistic models

- •5.2 Atomistic models and rate equations

- •5.2.1 Rate equations, controlling energies, and simulations

- •5.2.2 Elements of rate equation models

- •5.2.3 Regimes of condensation

- •5.2.4 General equations for the maximum cluster density

- •5.2.5 Comments on individual treatments

- •5.3 Metal nucleation and growth on insulating substrates

- •5.3.1 Microscopy of island growth: metals on alkali halides

- •5.3.2 Metals on insulators: checks and complications

- •5.4 Metal deposition studied by UHV microscopies

- •5.4.2 FIM studies of surface diffusion on metals

- •5.4.3 Energies from STM and other techniques

- •5.5 Steps, ripening and interdiffusion

- •5.5.2 Steps as sources: diffusion and Ostwald ripening

- •5.5.3 Interdiffusion in magnetic multilayers

- •Further reading for chapter 5

- •Problems and projects for chapter 5

- •6.1 The electron gas: work function, surface structure and energy

- •6.1.1 Free electron models and density functionals

- •6.1.2 Beyond free electrons: work function, surface structure and energy

- •6.1.3 Values of the work function

- •6.1.4 Values of the surface energy

- •6.2 Electron emission processes

- •6.2.1 Thermionic emission

- •6.2.4 Secondary electron emission

- •6.3.1 Symmetry, symmetry breaking and phase transitions

- •6.3.3 Magnetic surface techniques

- •6.3.4 Theories and applications of surface magnetism

- •Further reading for chapter 6

- •Problems and projects for chapter 6

- •7.1.1 Bonding in diamond, graphite, Si, Ge, GaAs, etc.

- •7.1.2 Simple concepts versus detailed computations

- •7.2 Case studies of reconstructed semiconductor surfaces

- •7.2.2 GaAs(111), a polar surface

- •7.2.3 Si and Ge(111): why are they so different?

- •7.2.4 Si, Ge and GaAs(001), steps and growth

- •7.3.1 Thermodynamic and elasticity studies of surfaces

- •7.3.2 Growth on Si(001)

- •7.3.3 Strained layer epitaxy: Ge/Si(001) and Si/Ge(001)

- •7.3.4 Growth of compound semiconductors

- •Further reading for chapter 7

- •Problems and projects for chapter 7

- •8.1 Metals and oxides in contact with semiconductors

- •8.1.1 Band bending and rectifying contacts at semiconductor surfaces

- •8.1.2 Simple models of the depletion region

- •8.1.3 Techniques for analyzing semiconductor interfaces

- •8.2 Semiconductor heterojunctions and devices

- •8.2.1 Origins of Schottky barrier heights

- •8.2.2 Semiconductor heterostructures and band offsets

- •8.3.1 Conductivity, resistivity and the relaxation time

- •8.3.2 Scattering at surfaces and interfaces in nanostructures

- •8.3.3 Spin dependent scattering and magnetic multilayer devices

- •8.4 Chemical routes to manufacturing

- •8.4.4 Combinatorial materials development and analysis

- •Further reading for chapter 8

- •9.1 Electromigration and other degradation effects in nanostructures

- •9.2 What do the various disciplines bring to the table?

- •9.3 What has been left out: future sources of information

- •References

- •Index

5.4 Metal deposition studied by UHV microscopies |

165 |

|

|

5.4Metal deposition studied by UHV microscopies

UHV microscope-based techniques (SEM, STEM, FIM and more recently STM, AFM, LEEM) plus diVraction techniques (including X-ray, SPA-LEED and helium scattering) examine the deposit/substrate combination in situ, without breaking the vacuum; we have discussed procedures for speci®c cases in chapters 2 and 3. Compared to ex situ TEM described in section 5.3.1 and 5.3.2, a wider set of substrates and deposits have been observed in recent years; some examples for metals on insulators were given in section 5.3.3.

In situ studies of metal deposition on metals are described in this section. These results are illustrative, in order to give a feel for the work; this is not a review article. Many review articles start with a statement: this is not an exhaustive treatment . . .! Perhaps this is just as well, no-one wants to be exhausted; but it means that one often has to go back to the original literature to be sure what went on. There are many examples where the primary literature represents a progress report, updated and maybe actually negated by subsequent work. Attempting to ®nd out what happened is often hard, but is preferable to repeating the work in ignorance of the original!

5.4.1In situ UHV SEM and LEEM of metals on metals

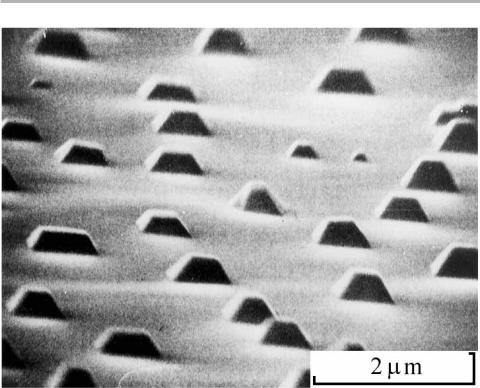

Ultra-high vacuum SEM and related techniques were developed by our group in Sussex, and used to study Stranski±Krastanov growth systems at elevated temperature. The SEM is good for visualizing strongly 3D objects, such as the (001) oriented Ag islands seen on Mo(001) in ®gure 5.12. Since adatoms must diVuse across the substrate to form the islands, we can see very directly that diVusion distances can be many micrometers (Hartig et al. 1978, Venables et al. 1984).

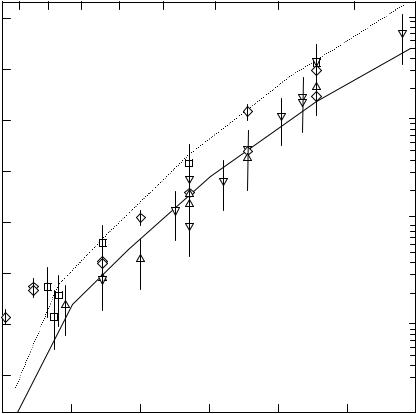

The systems Ag/W(110) and Ag/Fe(110) have been examined in detail with research students and other collaborators over a span of several years (Spiller et al. 1983, Jones & Venables 1985, Jones et al. 1990, Noro et al. 1995, 1996, Persaud et al. 1998). In these systems, 2ML of Ag form ®rst, and then ¯at Ag islands grow in (111) orientation. The experimental nucleation density N(T) is a strong function of substrate temperature, and the results of several Ag/W(110) experiments are shown in ®gure 5.13, in compar-

ison with a nucleation calculation nx(T) of the type outlined in section 5.2. In practice this proceeds by solving (5.14) iteratively, using the complete condensation solution as

the starting point.

Condensation is complete in this system, except at the highest temperatures studied, and the critical nucleus size is in the range 6±34, increasing with substrate temperature.

Energy values were deduced, Ea52.260.1, and the combination energy (Ed12Eb)5 0.6560.03 eV, within which Ed50.1560.1 and Eb50.257 0.05 eV (Jones et al. 1990). Note the errors are anti-correlated, since the combination energy is quite well deter-

mined by the absolute values of the data. What, however, makes these values interesting is that they can be compared with the best available calculations of metallic binding.

Comparison has been made with eVective medium theory, and the agreement is

166 5 Surface processes in epitaxial growth

Figure 5.12. In situ UHV SEM pictures of nucleation and growth of Ag on Mo(001), shown after 20 ML was deposited at T5550°C (from Hartig et al. 1978, reproduced with permission).

striking, as shown in table 5.3 with other values later. In particular, the results demonstrate the non-linearity of metallic binding with increasing coordination number. In the simplest nearest neighbor bond model which we explored in chapter 1, the adsorption energy on (111) corresponds to 3 bonds, or half the sublimation energy for a f.c.c. crystal. So for Ag, with L52.95 eV, such a model would give Ea51.47 eV, whereas the actual value is much larger. The same eVect is at work in the high binding energy of Ag2 molecules, quoted in section 5.3.1 in connection with island growth experiments. However, the last bonds to form are much weaker, so that in this case Eb is much less than L/650.49 eV. This is a general feature of eVective medium or embedded atom calculations on metals, discussed further in section 6.1.

The comparison between Ag/W and Ag/Fe(110) shows that the ®rst two layers are diVerent crystallographically, with two distorted Ag(111)-like layers on W(110) (Bauer et al. 1977), compared to a missing row c531 structure for the ®rst layer, followed by an Ag(111)-like second layer on Fe(110) (Noro et al. 1995). But adatom behavior on top of these two layers is very similar. UHV SEM methods can visualize the ®rst and second MLs, and the islands on top of these MLs in ®nite deposits, using biased secondary electron imaging described in chapter 3. DiVusion in these systems is discussed in section 5.5.2. Some eVects in the ®rst MLs of the related, but rather more reactive systems Cu and Au deposited onto W and Mo(110) have been studied by LEEM

5.4 Metal deposition studied by UHV microscopies |

167 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

T (K) |

|

|

|

800 |

750 |

700 |

650 |

600 |

550 |

500 |

450 |

|

9.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8.5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

i = 6 |

|

8.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

i = 9 |

|

) |

7.5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

/cm |

|

|

|

|

|

i = 17 |

|

|

(N |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Log |

7.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6.5 |

|

|

i = 22 |

|

|

|

|

|

6.0 |

|

|

|

|

Ag/W (110) Jones et al. (1990) |

||

|

|

|

i = 34 |

|

|

Triangles, two samples `clean' |

||

|

|

|

|

|

Squares, `contaminated, stepped' |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

5.5 |

|

|

|

|

Diamonds, Spiller et al. (1983) |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.2 |

|

1.4 |

1.6 |

|

1.8 |

2.0 |

2.2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1000/T (1/K) |

|

|

109

108

107

106

2 /cmN

Figure 5.13. Arrhenius plot of nucleation density for silver islands on 2MLAg/W(110) with nucleation model superimposed. Full line: Ea52.1, Eb50.25, Ed50.135 eV, compared to data on the ¯attest, cleanest samples; dashed line: Ed50.185 eV, other parameters unchanged, compared to data on stepped and/or slightly contaminated samples. Deposition rate R5

0.3 ML/min (from Spiller et al. 1983, and Jones et al. 1990, reproduced with permission).

(Bauer 1997). Although one might attempt to extract detailed binding parameters from such kinetic observations, this has not been emphasized, possibly because of their complexity, including quite marked crystallographic anisotropy. Several of the adsorption energies are however known from older thermal desorption and other thermodynamic measurements (Bauer 1984).

5.4.2FIM studies of surface diffusion on metals

At the other end of the length scale, the ®eld ion microscope (FIM) has been used to study individual atomic jumps and the formation and motion of small clusters. These

168 5 Surface processes in epitaxial growth

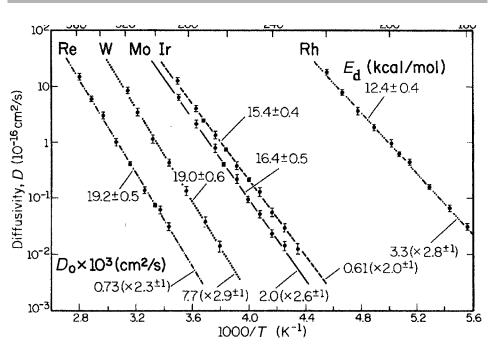

Figure 5.14. FIM measurements of surface diVusion of individual adatoms at a function of temperature on W(211), measured on the same sample. Note that energies Ed are quoted in kcal/mol (23.06 kcal/mol51 eV/atom). Errors in D0 are the factors in brackets (from Ehrlich 1991, after Wang & Ehrlich 1988, reproduced with permission).

observations are made at low temperature, with annealing at higher temperature for given times to eVect the jumps; the imaging ®eld is of course switched oV during the annealing periods. FIM works best for refractory metals, and high quality information has been obtained on diVusion coeYcients of individual atoms and small clusters in systems such as Re, W, Mo, Ir and Rh on tungsten, as shown in ®gure 5.14 for the W(211) surface (Ehrlich 1991, 1995, 1997). DiVusion on this surface is highly aniso-

Å

tropic, essentially moving along 1D channels parallel to the [011] direction, and avoiding jumps between channels. On higher symmetry surfaces, e.g. diVusion on (001) is observed to be isotropic, as it should be.

A particularly elegant application of FIM is to distinguish the hopping diVusion (pictured schematically in ®gure 5.3 and often assumed implicitly as the adatom diVusion mechanism) from exchange diVusion. If we draw a (001) surface of an f.c.c. crystal such as Pt, we know from chapter 1, problem 1.2, where an adatom will sit on this surface. So you can convince yourself that hopping diVusion will proceed in the close-packed K110L directions. By contrast, the exchange process consists of displacing a nearest neighbor of the adatom, and exchanging the adatom with it. The substrate atom `pops out' and the adatom becomes part of the substrate. In this case you can see that the direction of motion during diVusion is along K100L, at 45° to hopping diVusion