C5

.pdf

ated only by walking around it. From one side, the observer sees the Gaul’s intensely expressive face, from another his powerful torso, and from a third the woman’s limp and almost lifeless body. The man’s twisting posture, the almost theatrical gestures, and the emotional intensity of the suicidal act are hallmarks of the Pergamene baroque style and have close parallels in the later frieze of Zeus’s altar.

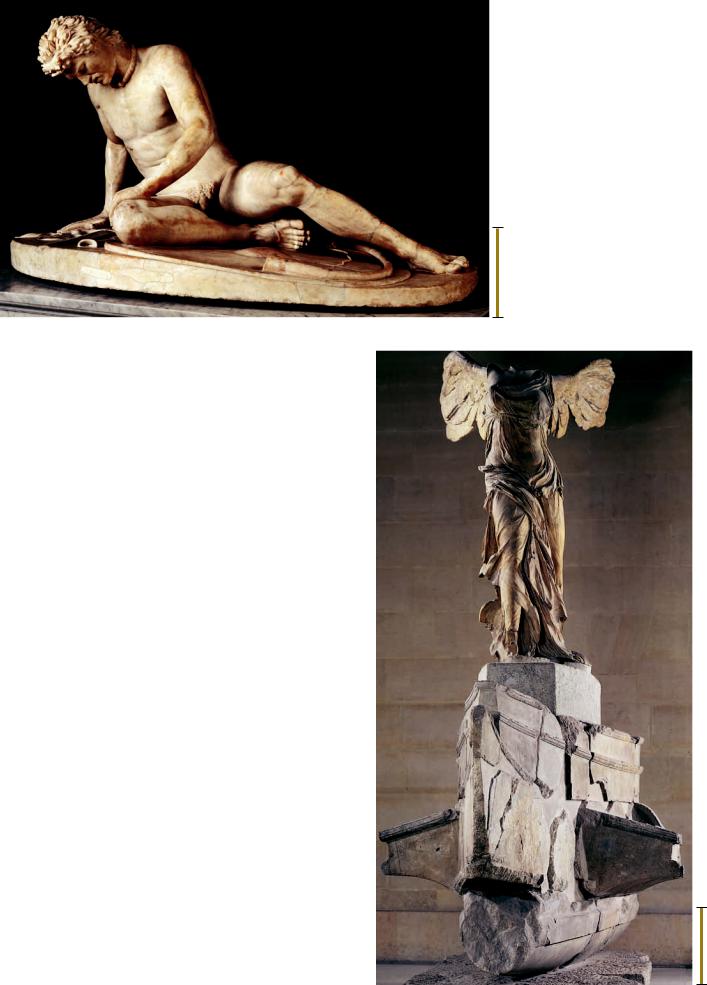

The third Gaul from this group is a trumpeter (FIG. 5-81) who collapses upon his large oval shield as blood pours from the gash in his chest. He stares at the ground with a pained expression. The Hellenistic figure recalls the dying warrior (FIG. 5-29) from the east pediment of the Temple of Aphaia at Aegina, but the pathos and drama of the suffering Gaul are far more pronounced. As in the suicide group and the gigantomachy frieze, the sculptor rendered the male musculature in an exaggerated manner. Note the tautness of the chest and the bulging veins of the left leg—implying that the unseen Attalid hero who has struck down this noble and savage foe must have been an extraordinary warrior. If this figure is the tubicen (trumpeter) Pliny mentioned as the work of the Pergamene master EPIGONOS, then Epigonos may be the sculptor of the entire group and the creator of the dynamic Hellenistic baroque style.

Sculpture

In different ways, Praxiteles, Skopas, and Lysippos had already taken bold steps in redefining the nature of Greek statuary. But Hellenistic sculptors went still further, both in terms of style and in expanding the range of subjects considered suitable for monumental sculpture.

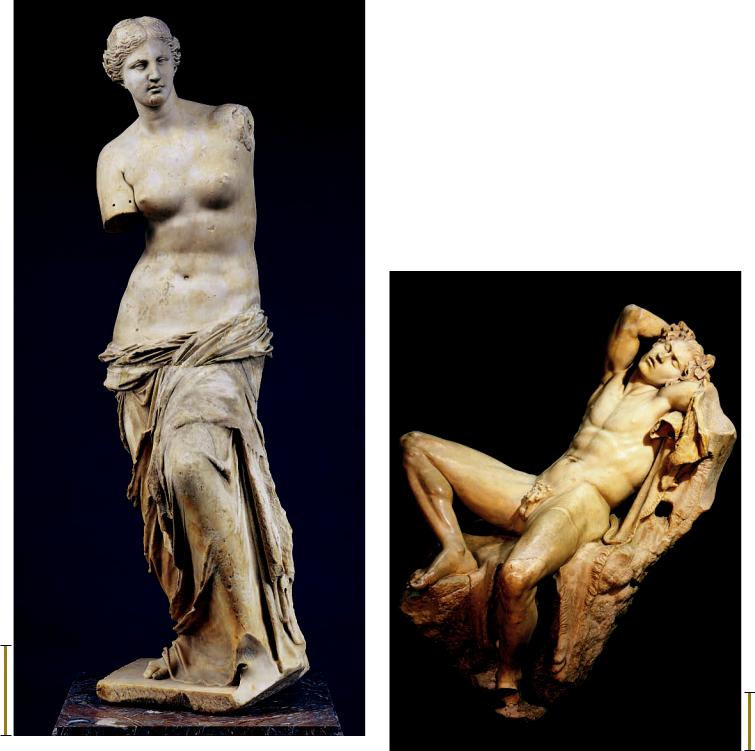

NIKE OF SAMOTHRACE One of the masterpieces of Hellenistic baroque sculpture was set up in the Sanctuary of the Great Gods on the island of Samothrace. The Nike of Samothrace (FIG. 5-82) has just alighted on the prow of a Greek warship. Her missing right arm was once raised high to crown the naval victor, just as Nike placed a wreath on Athena on the Altar of Zeus (FIG. 5-79). But the Pergamene

5-82 Nike alighting on a warship (Nike of Samothrace), from Samothrace, Greece, ca. 190 BCE. Marble, figure 8 1 high. Louvre, Paris.

Victory has just landed on a prow to crown a victor at sea. Her wings still beat, and the wind sweeps her drapery. The placement of the statue in a fountain of splashing water heightened the dramatic visual effect.

5-81 EPIGONOS(?), Dying Gaul. Roman marble copy of a bronze original of ca.

230–220 BCE, 3 – high. Museo Capitolino,

1

2

Rome.

The Gauls in the Pergamene victory groups were shown as barbarians with bushy hair, mustaches, and neck bands, but they were also portrayed as noble foes who fought to the end.

1 ft.

1 ft.

Hellenistic Per iod |

135 |

relief figure seems calm by comparison. The Samothracian Nike’s wings still beat, and the wind sweeps her drapery. Her himation bunches in thick folds around her right leg, and her chiton is pulled tightly across her abdomen and left leg.

The statue’s setting amplified its theatrical effect. The war galley was displayed in the upper basin of a two-tiered fountain. In the lower basin were large boulders. The fountain’s flowing water created

1 ft.

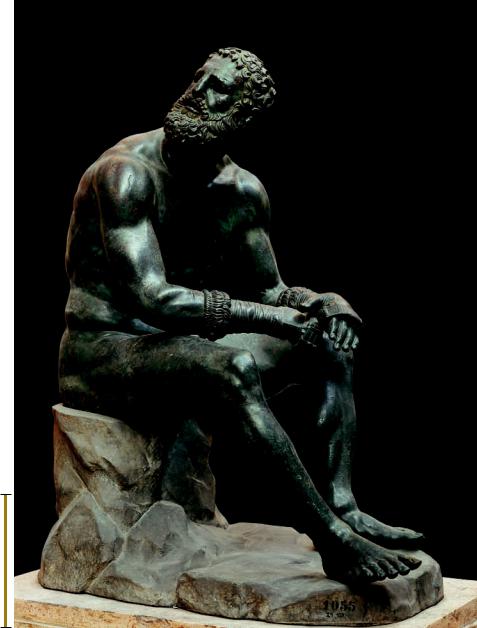

5-83 ALEXANDROS OF ANTIOCH-ON-THE-MEANDER, Aphrodite (Venus

de Milo), from Melos, Greece, ca. 150–125 BCE. Marble, 6 7 high.

Louvre, Paris.

Displaying the eroticism of many Hellenistic statues, this Aphrodite is more overtly sexual than the Knidian Aphrodite (FIG. 5-62). The goddess has a slipping garment to tease the spectator.

the illusion of rushing waves dashing up against the prow of the ship. The statue’s reflection in the shimmering water below accentuated the sense of lightness and movement. The sound of splashing water added an aural dimension to the visual drama. Art and nature were here combined in one of the most successful sculptures ever fashioned. In the Nike of Samothrace and other works in the Hellenistic baroque manner, sculptors resoundingly rejected the Polykleitan conception of a statue as an ideally proportioned, self-contained entity on a bare pedestal. The Hellenistic statues interact with their environment and appear as living, breathing, and intensely emotive human (or divine) presences.

VENUS DE MILO In the Hellenistic period, sculptors regularly followed Praxiteles’ lead in undressing Aphrodite, but they also openly explored the eroticism of the nude female form. The famous Venus de Milo (FIG. 5-83) is a larger-than-life-size marble statue of Aphrodite found on Melos together with its inscribed base (now lost) signed by

the sculptor, ALEXANDROS OF ANTIOCH-ON-THE-MEANDER. In this

statue, the goddess of love is more modestly draped than the Aphrodite of Knidos (FIG. 5-62) but is more overtly sexual. Her left hand (separately preserved) holds the apple Paris awarded her when he judged her the most beautiful goddess of all. Her right hand may have lightly grasped the edge of her drapery near the left hip in a halfhearted attempt to keep it from slipping farther down her body. The

1 ft.

5-84 Sleeping satyr (Barberini Faun), from Rome, Italy, ca. 230–200 BCE. Marble, 7 1 high. Glyptothek, Munich.

In this statue of a restlessly sleeping, drunken satyr, a Hellenistic sculptor portrayed a semihuman in a suspended state of conscious- ness—the antithesis of the Classical ideals of rationality and discipline.

136 Chapter 5 A N C I E N T G R E E C E

sculptor intentionally designed the work to tease the spectator, imbuing his partially draped Aphrodite with a sexuality absent from Praxiteles’ entirely nude image of the goddess.

BARBERINI FAUN Archaic statues smile at their viewers, and even when Classical statues look away from the viewer they are always awake and alert. Hellenistic sculptors often portrayed sleep. The suspension of consciousness and the entrance into the fantasy world of dreams—the antithesis of the Classical ideals of rationality and discipline—had great appeal for them. This newfound interest can be seen in a statue of a drunken, restlessly sleeping satyr (a semihuman follower of Dionysos) known as the Barberini Faun (FIG. 5-84) after the Italian cardinal who once owned it. The statue was found in Rome in the 17th century and restored (not entirely accurately) by Gianlorenzo Bernini, the great Italian Baroque sculptor (see Chapter 19). Bernini no doubt felt that this dynamic statue in the Pergamene manner was the work of a kindred spirit. The satyr has consumed too much wine and has thrown down his panther skin on a convenient rock and then fallen into a disturbed, intoxicated sleep. His brows are furrowed, and one can almost hear him snore.

1 ft.

Eroticism also comes to the fore in this statue. Although men had been represented naked in Greek art for hundreds of years, Archaic kouroi and Classical athletes and gods do not exude sexuality. Sensuality surfaced in the works of Praxiteles and his followers in the fourth century BCE. But the dreamy and supremely beautiful Hermes playfully dangling grapes before the infant Dionysos (FIG. 5-63) has nothing of the blatant sexuality of the Barberini Faun, whose wantonly spread legs focus attention on his genitals. Homosexuality was common in the man’s world of ancient Greece. It is not surprising that when Hellenistic sculptors began to explore the sexuality of the human body, they turned their attention to both men and women.

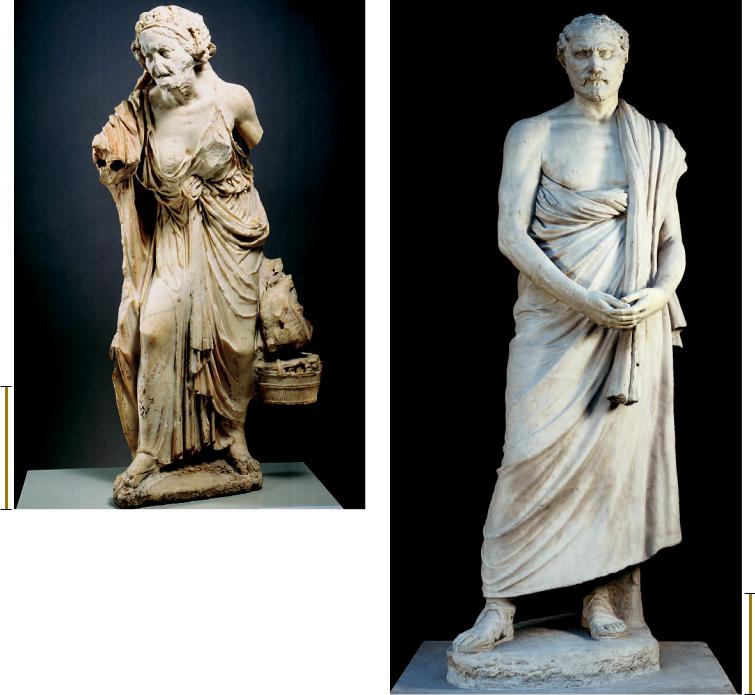

DEFEATED BOXER Although Hellenistic sculptors tackled an expanded range of subjects, they did not abandon such traditional themes as the Greek athlete. But they often rendered the old subjects in novel ways. This is certainly true of the magnificent bronze statue (FIG. 5-85) of a seated boxer, a Hellenistic original found in Rome and perhaps at one time part of a group. The boxer is not a victorious young athlete with a perfect face and body but a heavily battered, defeated veteran whose upward gaze may have been directed at the man

who had just beaten him. Too many punches from powerful hands wrapped in leather thongs—Greek boxers did not use the modern sport’s cushioned gloves—have distorted the boxer’s face. His nose is broken, as are his teeth. He has smashed, “cauliflower” ears. Inlaid copper blood drips from the cuts on his forehead, nose, and cheeks. How radically different is this rendition of a powerful bearded man from that of the noble warrior from Riace (FIGS. 5-35 and I-17) of the Early Classical period. The Hellenistic sculptor appealed not to the intellect but to the emotions when striving to evoke compassion for the pounded hulk of a oncemighty fighter.

5-85 Seated boxer, from Rome, Italy, Bronze, 4 2 high. Museo

Nazionale Romano–Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome.

Even when Hellenistic artists treated traditional themes, they approached them in novel ways. This bronze statue represents an older, defeated boxer with a broken nose and battered ears.

Hellenistic Per iod |

137 |

1 ft.

5-86 Old market woman, ca. 150–100 BCE. Marble, 4 – high.

1

2

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Consistent with the realism of much Hellenistic art, many statues portrayed old men and women from the lowest rungs of society.

They were never considered suitable subjects in earlier Greek statuary.

OLD MARKET WOMAN The realistic bent of much of Hellenistic sculpture—the very opposite of the Classical period’s ideal- ism—is evident above all in a series of statues of old men and women from the lowest rungs of the social order. Shepherds, fishermen, and drunken beggars are common—the kinds of people pictured earlier on red-figure vases but never before thought worthy of monumental statuary. One of the finest preserved statues of this type depicts a haggard old woman (FIG. 5-86) bringing chickens and a basket of fruits and vegetables to sell in the market. Her face is wrinkled, her body bent with age, and her spirit broken by a lifetime of poverty. She carries on because she must, not because she derives any pleasure from life. No one knows the purpose of these statues, but they attest to an interest in social realism absent in earlier Greek statuary.

Statues of the aged and the ugly are, of course, the polar opposites of the images of the young and the beautiful that dominated Greek art until the Hellenistic age, but they are consistent with the period’s changed character. The Hellenistic world was a cosmopolitan place, and the highborn could not help but encounter the poor and a growing number of foreigners (non-Greek “barbarians”) on a daily basis. Hellenistic art reflects this different social climate in the depiction of a much wider variety of physical types, including different ethnic types. The sensitive portrayal of Gallic warriors with their

138 Chapter 5 A N C I E N T G R E E C E

1 ft.

5-87 POLYEUKTOS, Demosthenes. Roman marble copy of a

bronze original of ca. 280 BCE, 6 7 – high. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek,

1

2

Copenhagen.

One of the earliest Hellenistic portraits, frequently copied, was Polyeuktos’s representation of the great orator Demosthenes as a frail man who possessed great courage and moral conviction.

shaggy hair, strange mustaches, and golden torques (FIG. 5-80 and 5-81) has already been noted. Africans, Scythians, and others, formerly only the occasional subject of vase painters, also entered the realm of monumental sculpture in Hellenistic art.

DEMOSTHENES These sculptures of foreigners and the urban poor, however realistic, are not portraits. Rather, they are sensitive studies of physical types. But the growing interest in the individual beginning in the Late Classical period did lead in the Hellenistic era to the production of true likenesses of specific persons. In fact, one of the

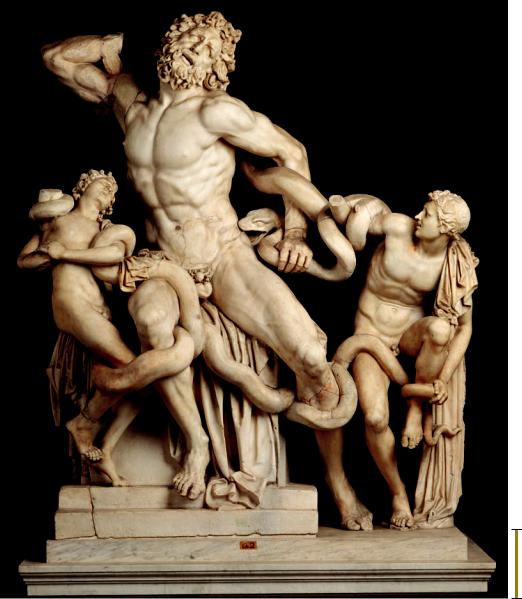

5-88 ATHANADOROS, HAGESANDROS, and POLYDOROS OF RHODES, Laocoön

and his sons, from Rome, Italy, early

first century CE. Marble, 7 10 – high.

1

2

Musei Vaticani, Rome.

Hellenistic style lived on in Rome. Although stylistically akin to Pergamene sculpture, this statue of sea serpents attacking Laocoön and his two sons matches the account given only in the Aeneid.

1 ft.

great achievements of Hellenistic artists was the redefinition of portraiture. In the Classical period, Kresilas was admired for having made the noble Pericles appear even nobler in his portrait (FIG. 5-41). But in Hellenistic times sculptors sought not only to record the actual appearance of their subjects in bronze and stone but also to capture the essence of their personalities in likenesses that were at once accurate and moving.

One of the earliest of these, perhaps the finest of the Hellenistic age and frequently copied in Roman times, was a bronze portrait statue of Demosthenes (FIG. 5-87) by POLYEUKTOS. The original was set up in the Athenian agora in 280 BCE, 42 years after the great orator’s death. Demosthenes was a frail man and in his youth even suffered from a speech impediment, but he had enormous courage and great moral conviction. A veteran of the disastrous battle against Philip II at Chaeronea, he repeatedly tried to rally opposition to Macedonian imperialism, both before and after Alexander’s death. In the end, when it was clear the Macedonians would capture him, he took his own life by drinking poison.

Polyeuktos rejected Kresilas’s and Lysippos’s notions of the purpose of portraiture and did not attempt to portray a supremely confident leader with a magnificent physique. His Demosthenes has an aged and slightly stooped body. The orator clasps his hands nervously in front of him as he looks downward, deep in thought. His

face is lined, his hair is receding, and his expression is one of great sadness. Whatever physical discomfort Demosthenes felt is here joined by an inner pain, his deep sorrow over the tragic demise of democracy at the hands of the Macedonian conquerors.

Hellenistic Art under Roman Patronage

In the opening years of the second century BCE, the Roman general Flaminius defeated the Macedonian army and declared the old poleis of Classical Greece free once again. The city-states never regained their former glory, however. Greece became a Roman province in 146 BCE. When, 60 years later, Athens sided with King Mithridates VI of Pontus (r. 120–63 BCE) in his war against Rome, the general Sulla crushed the Athenians. Thereafter, Athens retained some of its earlier prestige as a center of culture and learning, but politically it was just another city in the ever-expanding Roman Empire. Nonetheless, Greek artists continued to be in great demand, both to furnish the Romans with an endless stream of copies of Classical and Hellenistic masterpieces and to create new statues à la grecque (in the Greek style) for Roman patrons.

LAOCOÖN One such work is the famous group (FIG. 5-88) of the Trojan priest Laocoön and his sons, which was unearthed in Rome in

Hellenistic Per iod |

139 |

1506 in the presence of the great Italian Renaissance artist Michelangelo. The marble group, long believed an original of the second century BCE, was found in the remains of the palace of the emperor Titus (r. 79–81 CE), exactly where Pliny had seen it more than 14 centuries before. Pliny attributed the statue to three sculptors—ATHANADOROS,

HAGESANDROS, and POLYDOROS OF RHODES—whom most art histori-

ans now think worked in the early first century CE. They probably based their group on a Hellenistic masterpiece depicting Laocoön and only one son. Their variation on the original added the son at Laocoön’s left (note the greater compositional integration of the two other figures) to conform with the Roman poet Vergil’s account in the Aeneid. Vergil vividly described the strangling of Laocoön and his two sons by sea serpents while sacrificing at an altar. The gods who favored the Greeks in the war against Troy had sent the serpents to punish Laocoön, who had tried to warn his compatriots about the danger of bringing the Greeks’ wooden horse within the walls of their city.

In Vergil’s graphic account, Laocoön suffered in terrible agony, and the sculptors communicated the torment of the priest and his sons in a spectacular fashion in the marble group. The three Trojans writhe in pain as they struggle to free themselves from the death grip of the serpents. One bites into Laocoön’s left hip as the priest lets out a ferocious cry. The serpent-entwined figures recall the suffering giants of the great frieze of the Altar of Zeus at Pergamon, and Laocoön himself is strikingly similar to Alkyoneos (FIG. 5-79), Athena’s opponent. In fact, many scholars believe that a Pergamene statuary group of the second century BCE was the inspiration for the three Rhodian sculptors.

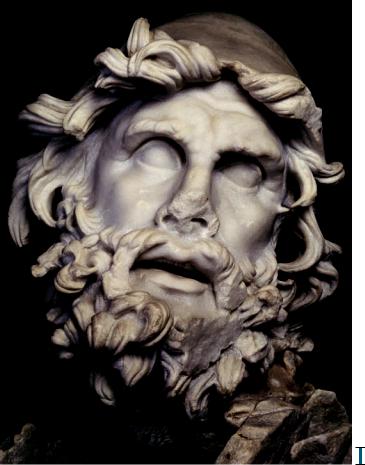

SPERLONGA That the work seen by Pliny and displayed in the Vatican Museums today was made for Romans rather than Greeks was confirmed in 1957 by the discovery of fragments of several Hel- lenistic-style groups illustrating scenes from Homer’s Odyssey. These fragments were found in a grotto that served as the picturesque summer banquet hall of the seaside villa of the Roman emperor Tiberius (r. 14–37 CE) at Sperlonga, some 60 miles south of Rome. One of these groups—depicting the monster Scylla attacking Odysseus’s ship—is signed by the same three sculptors Pliny cited as the creators of the Laocoön group. Another of the groups, installed around a central pool in the grotto, depicted the blinding of the Cyclops Polyphemos by Odysseus and his comrades, an incident also set in a cave in the Homeric epic. The head of Odysseus (FIG. 5-89) from this theatrical group is one of the finest sculptures of antiquity. The hero’s cap can barely contain his swirling locks of hair. Even Odysseus’s beard seems to be swept up in the emotional intensity of the moment. The parted lips and the deep shadows produced by sharp undercutting add drama to the head, which complemented Odysseus’s agitated body.

1 in.

5-89 ATHANADOROS, HAGESANDROS, and POLYDOROS OF RHODES,

head of Odysseus, from Sperlonga, Italy, early first century CE. Marble,

2 1– high. Museo Archeologico, Sperlonga.

1

4

This emotionally charged depiction of Odysseus was part of a mythological statuary group that the Laocoön sculptors made for a grotto at the emperor Tiberius’s seaside villa at Sperlonga.

At Tiberius’s villa in Sperlonga and in Titus’s palace in Rome, the baroque school of Hellenistic sculpture lived on long after Greece ceased to be a political force. When Rome inherited the Pergamene kingdom from the last of the Attalids in 133 BCE, it also became heir to the Greek artistic legacy, and what Rome adopted from Greece it in turn passed on to the medieval and modern worlds. If Greece was peculiarly the inventor of the European spirit, Rome surely was its propagator and amplifier.

140 Chapter 5 A N C I E N T G R E E C E

T H E B I G P I C T U R E

A N C I E N T G R E E C E

GEOMETRIC AND ORIENTALIZING ART, ca. 900–600 BCE

Homer lived during the eighth century BCE, the era when the city-states of Classical Greece took shape, the Olympic Games were founded (776 BCE), and the Greeks began to trade with their neighbors to both east and west.

Also at this time, the human figure returned to Greek art in the form of bronze statuettes and simple silhouettes amid other abstract motifs on Geometric vases.

Increasing contact with the civilizations of the Near East precipitated the so-called Orientalizing phase (ca. 700–600 BCE) of Greek art, when Eastern monsters began to appear on black-figure vases.

Dipylon krater, Athens, ca. 740 BCE

ARCHAIC ART, ca. 600–480 BCE

Around 600 BCE, the first life-size stone statues appeared in Greece. The earliest kouroi emulated the frontal poses of Egyptian statues, but artists depicted the young men nude, the way Greek athletes competed at Olympia.

During the course of the sixth century BCE, Greek sculptors refined the proportions and added “Archaic smiles” to the faces of their statues to make them seem more lifelike.

The Archaic age also saw the erection of the first stone temples with peripteral colonnades and the codification of the Doric and Ionic orders.

The Andokides Painter invented red-figure vase painting around 530 BCE. Euphronios and Euthymides rejected the age-old composite view for the human figure and experimented with foreshortening.

EARLY AND HIGH CLASSICAL ART, ca. 480–400 BCE

Kroisos, kouros from Anavysos, ca. 530 BCE

The Classical period opened with the Persian sack of the Athenian Acropolis in 480 BCE and the Greek victory a year later. The fifth century BCE was the golden age of Greece, when Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides wrote their plays, and Herodotus, the “father of history,” lived.

During the Early Classical period (480–450 BCE), sculptors revolutionized statuary by introducing contrapposto (weight shift) to their figures.

In the High Classical period (450–400 BCE), Polykleitos developed a canon of proportions for the perfect statue. Iktinos and Kallikrates similarly applied mathematical formulas to temple design in the belief that beauty resulted from the use of harmonic numbers.

Under the patronage of Pericles and the artistic directorship of Phidias, the Athenians rebuilt the Acropolis after 447 BCE. The Parthenon, Phidias’s Athena Parthenos, and the works of Polykleitos have defined what it means to be “Classical” ever since.

LATE CLASSICAL ART, ca. 400–323 BCE

In the aftermath of the Peloponnesian War, which ended in 404 BCE, Greek artists, while still adhering to the philosophy that humanity was the “measure of all things,” began to focus more on the real world of appearances than on the ideal world of perfect beings.

Late Classical sculptors humanized the remote deities, athletes, and heroes of the fifth century BCE. Praxiteles, for example, caused a sensation when he portrayed Aphrodite undressed. Lysippos depicted Herakles as a strong man so weary that he needed to lean on his club for support.

In architecture, the ornate Corinthian capital became increasingly popular, breaking the monopoly of the Doric and Ionic orders.

The period closed with Alexander the Great, who transformed the Mediterranean world politically and ushered in a new artistic age as well.

HELLENISTIC ART, ca. 323–30 BCE

The Hellenistic age extends from the death of Alexander until the death of Cleopatra, when Egypt became a province of the Roman Empire. The great cultural centers of the era were no longer the city-states of Archaic and Classical Greece but royal capitals such as Alexandria in Egypt and Pergamon in Asia Minor.

In art, both architects and sculptors broke most of the rules of Classical design. At Didyma, for example, a temple to Apollo was erected that had no roof and contained a smaller temple within it.

Hellenistic sculptors explored new subjects—Gauls with strange mustaches and necklaces, impoverished old women—and treated traditional subjects in new ways—athletes with battered bodies and faces, openly erotic goddesses. Artists delighted in depicting violent movement and unbridled emotion.

Parthenon, Acropolis, Athens,

447–438 BCE

Praxiteles, Aphrodite of Knidos,

ca. 350–340 BCE

Altar of Zeus, Pergamon,

ca. 175 BCE

1 ft.

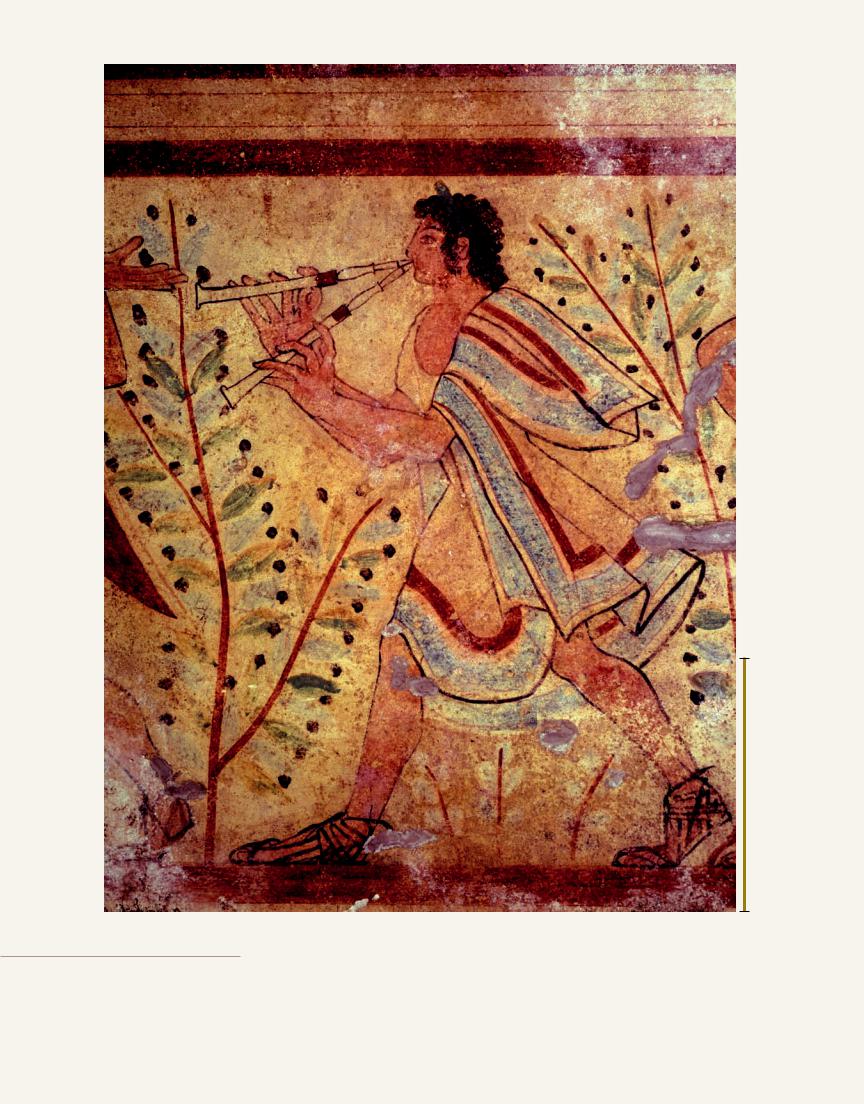

6-1 Double-flute player, detail of a mural painting in the Tomb of the Leopards, Tarquinia, Italy, ca. 480–470 BCE.

Detail 3 3– high.

1

2

Although Etruscan art owes an obvious stylistic debt to Greek art, painted murals in monumental tombs such as the Tomb of the Leopards at Tarquinia are unknown in Greece at the same time.