C5

.pdf

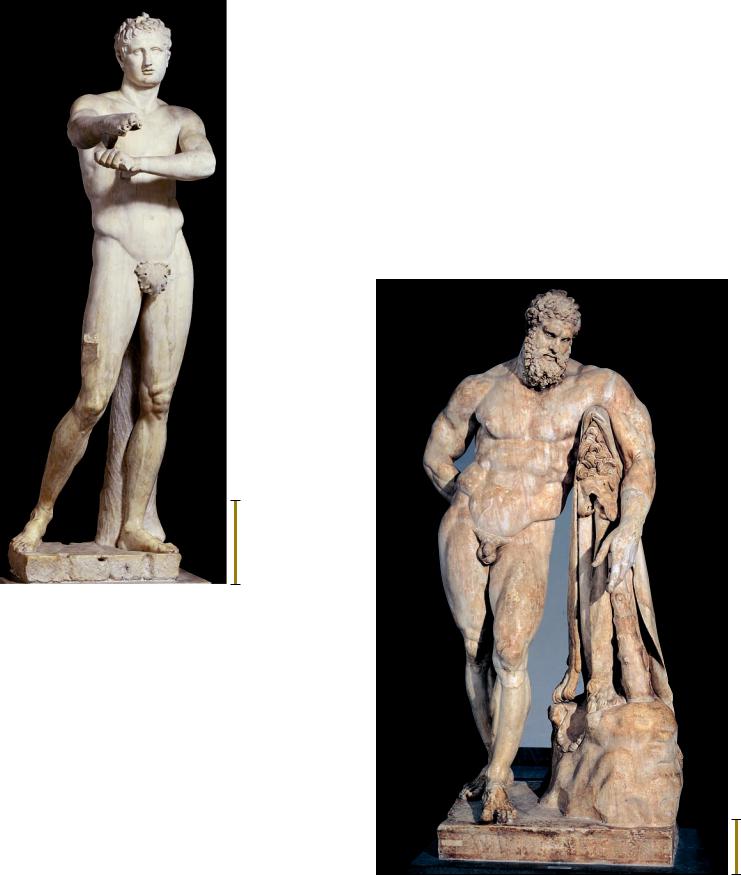

5-65 LYSIPPOS,

Apoxyomenos

(Scraper). Roman marble copy of a bronze original of

ca. 330 BCE, 6 9 high.

Musei Vaticani, Rome.

Lysippos introduced a new canon of proportions and a nervous energy to his statues. He also broke down the dominance of the frontal view and encouraged viewing his statues from multiple angles.

1 ft.

scrape his left arm. At the same time, he will shift his weight and reverse the positions of his legs. Lysippos also began to break down the dominance of the frontal view in statuary and encouraged the observer to look at his athlete from multiple angles. Because Lysippos represented the athlete with his right arm boldly thrust forward, the figure breaks out of the shallow rectangular box that defined the boundaries of earlier statues. To comprehend the action, the observer must move to the side and view Lysippos’s work at a threequarter angle or in full profile.

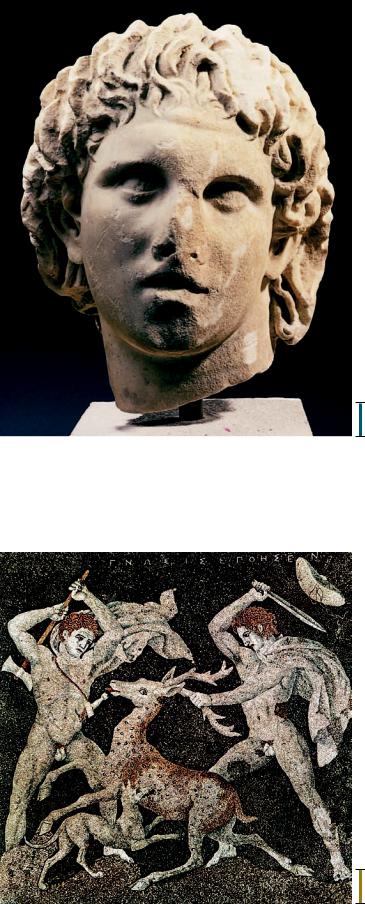

To grasp the full meaning of another work of Lysippos, a colossal statue (FIG. 5-66) depicting a weary Herakles, the viewer must walk around it. Once again, the original is lost. The most impressive of the surviving marble copies is nearly twice life-size and was exhibited in the Baths of Caracalla in Rome. Like the marble copy of Polykleitos’s Doryphoros (FIG. 5-40) from the Roman palaestra at

his frail old age. Most remarkable of all, the hunter himself looks out at the viewer, inviting sympathy and creating an emotional bridge between the spectator and the artwork inconceivable in the art of the High Classical period.

LYSIPPOS The third great Late Classical sculptor, LYSIPPOS OF SIKYON, won such renown that Alexander the Great selected him to create his official portrait. (Alexander could afford to employ the best. The Macedonian kingdom enjoyed vast wealth. King Philip hired the leading thinker of his age, Aristotle, as the young Alexander’s tutor.) Lysippos introduced a new canon of proportions in which the bodies were more slender than those of Polykleitos— whose own canon continued to exert enormous influence—and the heads roughly one-eighth the height of the body rather than oneseventh, as in the previous century. The new proportions are apparent in one of Lysippos’s most famous works, a bronze statue of an apoxyomenos (an athlete scraping oil from his body after exercising), known, as usual, only from Roman copies in marble (FIG. 5-65). A comparison with Polykleitos’s Doryphoros (FIG. 5-40) reveals more than a change in physique. A nervous energy, lacking in the balanced form of the Doryphoros, runs through Lysippos’s Apoxyomenos. The strigil (scraper) is about to reach the end of the right arm, and at any moment the athlete will switch it to the other hand so that he can

1 ft.

5-66 LYSIPPOS, Weary Herakles (Farnese Herakles). Roman marble copy from Rome, Italy, signed by GLYKON OF ATHENS, of a bronze original of ca. 320 BCE, 10 5 high. Museo Archeologico Nazionale,

Naples.

Lysippos’s portrayal of Herakles after the hero obtained the golden apples of the Hesperides ironically shows the mythological strong man as so weary that he must lean on his club for support.

Late Classical Per iod |

125 |

Pompeii, Lysippos’s muscle-bound Greek hero provided inspiration for Romans who came to the baths to exercise. (The copyist, GLYKON OF ATHENS, signed the statue. Lysippos’s name is not mentioned, but the educated Roman public did not need a label to identify the famous work.) In the hands of Lysippos, however, the exaggerated muscular development of Herakles is poignantly ironic, for the sculptor depicted the strong man as so weary that he must lean on his club for support. Without that prop, Herakles would topple over. Lysippos and other fourth-century BCE artists rejected stability and balance as worthy goals for statuary.

Herakles holds the golden apples of the Hesperides in his right hand behind his back—unseen unless the viewer walks around the statue. Lysippos’s subject is thus the same as that of the metope (FIG. 5-33) of the Early Classical Temple of Zeus at Olympia, but the fourth-century BCE Herakles is no longer serene. Instead of expressing joy, or at least satisfaction, at having completed one of the impossible 12 labors, he is almost dejected. Exhausted by his physical efforts, he can think only of his pain and weariness, not of the reward of immortality that awaits him. Lysippos’s portrayal of Herakles in this statue is an eloquent testimony to Late Classical sculptors’ interest in humanizing the great gods and heroes of the Greeks. In this respect, despite their divergent styles, Praxiteles, Skopas, and Lysippos followed a common path.

Alexander the Great

and Macedonian Court Art

Alexander the Great’s favorite book was the Iliad, and his own life was very much like an epic saga, full of heroic battles, exotic places, and unceasing drama. Alexander was a man of singular character, an inspired leader with boundless energy and an almost foolhardy courage. He personally led his army into battle on the back of Bucephalus, the wild and mighty steed only he could tame and ride (FIG. 5-70).

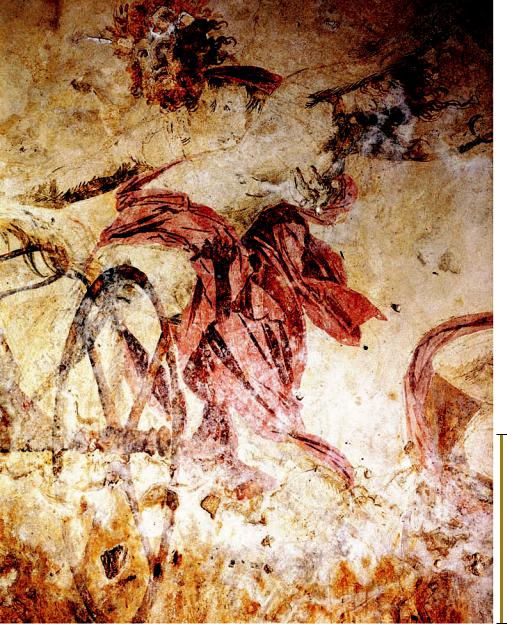

ALEXANDER’S PORTRAITS Ancient sources reveal that Alexander believed only Lysippos had captured his essence in a portrait, and that is why only he was authorized to sculpt the king’s image. Lysippos’s most famous portrait of the Macedonian king was a full-length heroically nude bronze statue of Alexander holding a lance and turning his head toward the sky. Plutarch reported that an epigram inscribed on the base stated that the statue depicted Alexander gazing at Zeus and proclaiming, “I place the earth under my sway. You, O Zeus, keep Olympus.” Plutarch further stated that the portrait had “leonine” hair and a “melting glance.”5 The Lysippan original is lost, and because Alexander was portrayed so many times for centuries after his death, it is very difficult to determine which of the many surviving images is most faithful to the fourth-century BCE portrait. A leading candidate is a third-century BCE marble head (FIG. 5-67) from Pella, the capital of Macedonia and Alexander’s birthplace. It has the sharp turn of the head and thick mane of hair that were key ingredients of Lysippos’s portrait. The sculptor’s treatment of the features also is consistent with the style of the later fourth century BCE. The deep-set eyes and parted lips recall the manner of Skopas, and the delicate handling of the flesh brings to mind the faces of Praxitelean statues. Although not a copy, this head very likely approximates the young king’s official portrait and provides insight into Alexander’s personality as well as the art of Lysippos.

PELLA MOSAICS Alexander’s palace has not been excavated, but the sumptuousness of life at the Macedonian court is evident from the costly objects found in Macedonian graves and from the abundance of mosaics (see “Mosaics,” Chapter 8, page 223)

1 in.

5-67 Head of Alexander the Great, from Pella, Greece, third century BCE. Marble, 1 high. Archaeological Museum, Pella.

Lysippos was the official portrait sculptor of Alexander the Great. This third-century BCE sculpture has the sharp turn of the head and thick mane of hair of Lysippos’s statue of Alexander with a lance.

1 ft.

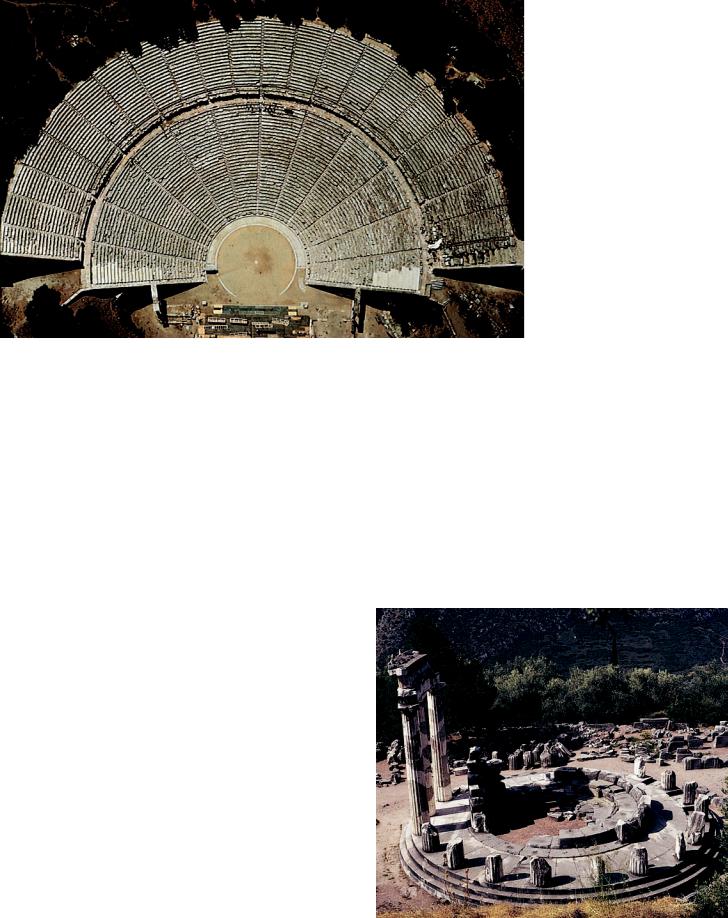

5-68 GNOSIS, Stag hunt, from Pella, Greece, ca. 300 BCE. Pebble mosaic, figural panel 10 2 high. Archaeological Museum, Pella.

The floor mosaics at the Macedonian capital of Pella are of the early type made with pebbles of various natural colors. This stag hunt by Gnosis bears the earliest known signature of a mosaicist.

126 Chapter 5 A N C I E N T G R E E C E

uncovered at Pella in the homes of the wealthy. The Pella mosaics are pebble mosaics. The floors consist of small stones of various colors collected from beaches and riverbanks and set into a thick coat of cement. The finest pebble mosaic yet to come to light has a stag hunt (FIG. 5-68) as its emblema (central framed panel), bordered in turn by an intricate floral pattern and a stylized wave motif (not shown in the illustration). The artist signed his work in the same manner as proud Greek vase painters and potters did: “GNOSIS made it.” This is the earliest mosaicist’s signature known, and its prominence in the design undoubtedly attests to the artist’s reputation. The house owner wanted guests to know that Gnosis himself, and not an imitator, created this floor.

The Pella stag hunt, with its light figures against a dark ground, has much in common with red-figure painting. In the pebble mosaic, however, thin strips of lead or terracotta define most of the contour lines and some of the interior details. Subtle gradations of yellow, brown, and red, as well as black, white, and gray pebbles suggest the interior volumes. The musculature of the hunters, and even their billowing cloaks and the animals’ bodies, are modeled by shading. Such use of light and dark to suggest volume is rarely seen on Greek

painted vases, although examples do exist. Monumental painters, however, commonly used shading. The Greek term for shading was skiagraphia (literally, “shadow painting”), and it was said to have been invented by an Athenian painter of the fifth century BCE named Apollodoros. Gnosis’s emblema, with its sparse landscape setting, probably reflects contemporaneous panel painting.

HADES AND PERSEPHONE Recent excavations at Vergina have provided valuable additional information about Macedonian art and about Greek mural painting. One of the most important finds is a painted tomb with a representation of Hades, lord of the Underworld, abducting Persephone, the daughter of Demeter, the goddess of grain. The mural (FIG. 5-69) is remarkable for its intense drama and for the painter’s use of foreshortening and shading. Hades holds the terrified seminude Persephone in his left arm and steers his racing chariot with his right as Persephone’s garments and hair blow in the wind. The artist depicted the heads of both figures and even the chariot’s wheels in three-quarter views. The chariot, in fact, seems to be bursting into the viewer’s space. Especially noteworthy is the way the painter used short dark brush strokes to

5-69 Hades abducting Persephone, detail of a wall painting in tomb 1, Vergina, Greece, mid-fourth century BCE.

3 3 – high.

1

2

The intense drama, three-quarter views, and shading in this representation of the lord of the Underworld kidnapping Demeter’s daughter are characteristics

of mural painting at the time of Alexander.

1 ft.

Late Classical Per iod |

127 |

1 ft.

5-70 PHILOXENOS OF ERETRIA, Battle of Issus, ca. 310 BCE. Roman copy (Alexander Mosaic) from the House of the Faun, Pompeii, Italy, late second or early first century BCE. Tessera mosaic, 8 10 16 9 . Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples.

Philoxenos’s Battle of Issus (see also FIG. 5-1) was considered one of the greatest paintings of antiquity. In it he captured the psychological intensity of the confrontation between the two kings.

suggest shading on the under side of Hades’ right arm, on Persephone’s torso, and elsewhere. Although fragmentary, the Vergina mural is a precious document of the almost totally lost art of monumental painting in ancient Greece.

BATTLE OF ISSUS Further insight into developments in painting at the time of Alexander comes from a large mosaic that decorated the floor of one room of a lavishly appointed Roman house at Pompeii. In the Alexander Mosaic (FIG. 5-70), as it is usually called, the mosaicist employed tesserae (tiny stones or pieces of glass cut to the desired size and shape) instead of pebbles (see “Mosaics,” Chapter 8, page 223). The subject is a great battle between the armies of Alexander the Great and the Persian king Darius III, probably the battle of Issus in southeastern Turkey, when Darius fled the battlefield in his chariot in humiliating defeat. The mosaic dates to the late second or early first century BCE. It is widely believed to be a reasonably faithful copy of Battle of Issus, a famous panel painting of ca. 310 BCE made by PHILOXENOS OF ERETRIA for King Cassander, one of Alexander’s successors. Some scholars have proposed, however, that the mosaic is a copy of a painting by one of the few Greek female artists whose name is known, Helen of Egypt.

Battle of Issus is notable for the artist’s technical mastery of problems that had long fascinated Greek painters. Even Euthymides would have marveled at the fourth-century BCE painter’s depiction of the rearing horse (FIG. 5-1) seen in a three-quarter rear view below Darius. The subtle modulation of the horse’s rump through shading in browns and yellows is much more accomplished than the comparable attempts at shading in the Pella mosaic (FIG. 5-68) or the Vergina mural (FIG. 5-69). Other details are even more impres-

sive. The Persian to the right of the rearing horse has fallen to the ground and raises, backward, a dropped Macedonian shield to protect himself from being trampled. Philoxenos recorded the reflection of the man’s terrified face on the polished surface of the shield. Everywhere in the scene, men, animals, and weapons cast shadows on the ground. The interest of Greek painters in the reflection of insubstantial light on a shiny surface, and in the absence of light (shadows), was far removed from earlier painters’ preoccupation with the clear presentation of weighty figures seen against a blank background. The Greek painter here truly opened a window into a world filled not only with figures, trees, and sky but also with light. This Classical Greek notion of what a painting should be characterizes most of the history of art in the Western world from the Renaissance on.

Most impressive about Battle of Issus, however, is the psychological intensity of the drama unfolding before the viewer’s eyes. Alexander is on horseback leading his army into battle, recklessly one might say, without even a helmet to protect him. He drives his spear through one of Darius’s trusted “Immortals,” who were sworn to guard the king’s life, while the Persian’s horse collapses beneath him. The Macedonian king is only a few yards away from Darius, and Alexander directs his gaze at the Persian king, not at the man impaled on his now-useless spear. Darius has called for retreat. In fact, his charioteer is already whipping the horses and speeding the king to safety. Before he escapes, Darius looks back at Alexander and in a pathetic gesture reaches out toward his brash foe. But victory has slipped from his hands. Pliny said Philoxenos’s painting of the battle between Alexander and Darius was “inferior to none.”6 It is easy to see why he reached that conclusion.

128 Chapter 5 A N C I E N T G R E E C E

Architecture

In architecture, as in sculpture and painting, the Late Classical period was a time of innovation and experimentation.

THEATER OF EPIDAUROS In ancient Greece, plays were not performed repeatedly over months or years as they are today but only during sacred festivals. Greek drama was closely associated with religious rites and was not pure entertainment. At Athens in the fifth century BCE, for example, the great tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides were performed at the Dionysos festival in the theater dedicated to the god on the southern slope of the Acropolis. The finest theater in Greece, however, constructed shortly after Alexander the Great was born, is located at Epidauros in the Peloponnesos. The architect was POLYKLEITOS THE YOUNGER, possibly a nephew of the great fifth-century sculptor. His theater (FIG. 5-71) is still used for performances of ancient Greek dramas.

The precursor of the formal Greek theater was a place where ancient rites, songs, and dances were performed. This circular piece of earth with a hard, level surface later became the orchestra of the theater. Orchestra literally means “dancing place.” The actors and the chorus performed there, and at Epidauros an altar to Dionysos stood at the center of the circle. The spectators sat on a slope overlooking the orchestra—the theatron, or “place for seeing.” When the Greek theater took architectural shape, the auditorium (cavea, Latin for “hollow place, cavity”) was always situated on a hillside. The cavea at Epidauros, composed of wedge-shaped sections (cunei, singular cuneus) of stone benches separated by stairs, is somewhat greater than a semicircle in plan. The auditorium is 387 feet in diameter, and its 55 rows of seats accommodated about 12,000 spectators. They entered the theater via a passageway between the seating area and the scene building (skene), which housed dressing rooms for the actors and also formed a backdrop for the plays. The design is simple but perfectly suited to its function. Even in antiquity the Epidauros theater won renown for the harmony of its proportions. Although spectators sitting in some of the seats would have had a poor view of the skene, all had unobstructed views of the orchestra. Because of the open-air cavea’s excellent acoustics, everyone could hear the actors and chorus.

5-71 POLYKLEITOS THE YOUNGER,

Theater, Epidauros, Greece, ca. 350 BCE.

The Greeks always situated their theaters on hillsides, which supported the cavea of stone seats overlooking the circular orchestra. The Epidauros theater is the finest in Greece. It accommodated 12,000 spectators.

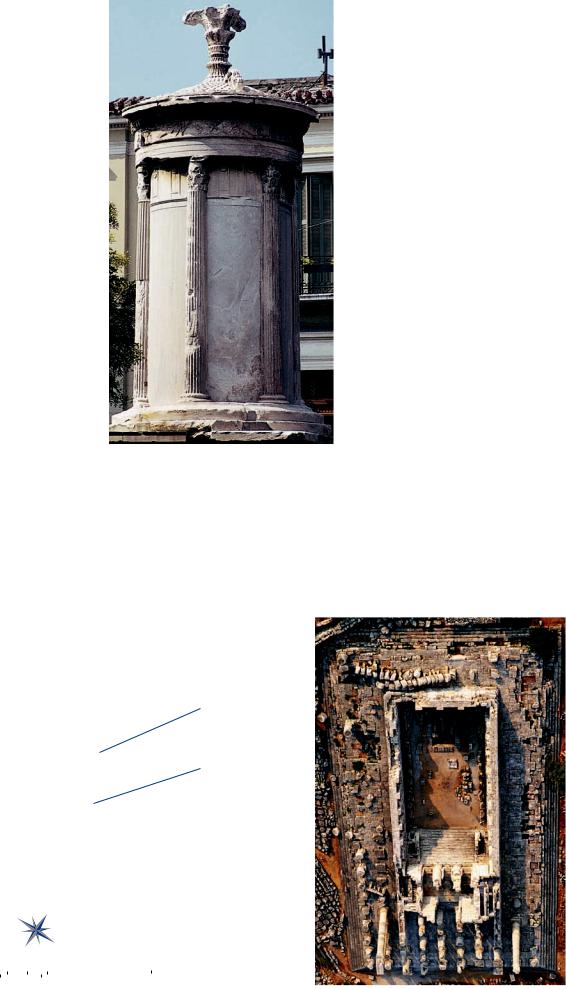

CORINTHIAN CAPITALS The theater at Epidauros is situated some 500 yards southeast of the sanctuary of Asklepios, and Polykleitos the Younger worked there as well. He was the architect of the tholos, the circular shrine that probably housed the sacred snakes of the healing god. That building lies in ruins today, its architectural fragments removed to the local museum, but an approximate idea of its original appearance can be gleaned from the somewhat earlier and partially reconstructed tholos (FIG. 5-72) at Delphi that THEODOROS OF PHOKAIA designed. Both tholoi had an exterior colonnade of Doric columns. Inside, however, the columns had

5-72 THEODOROS OF PHOKAIA, Tholos, Delphi, Greece, ca. 375 BCE.

Theodoros of Phokaia’s tholos at Delphi, although in ruins, is the bestpreserved example of a round temple of the Classical period. It had Doric columns on the exterior and Corinthian columns inside.

Late Classical Per iod |

129 |

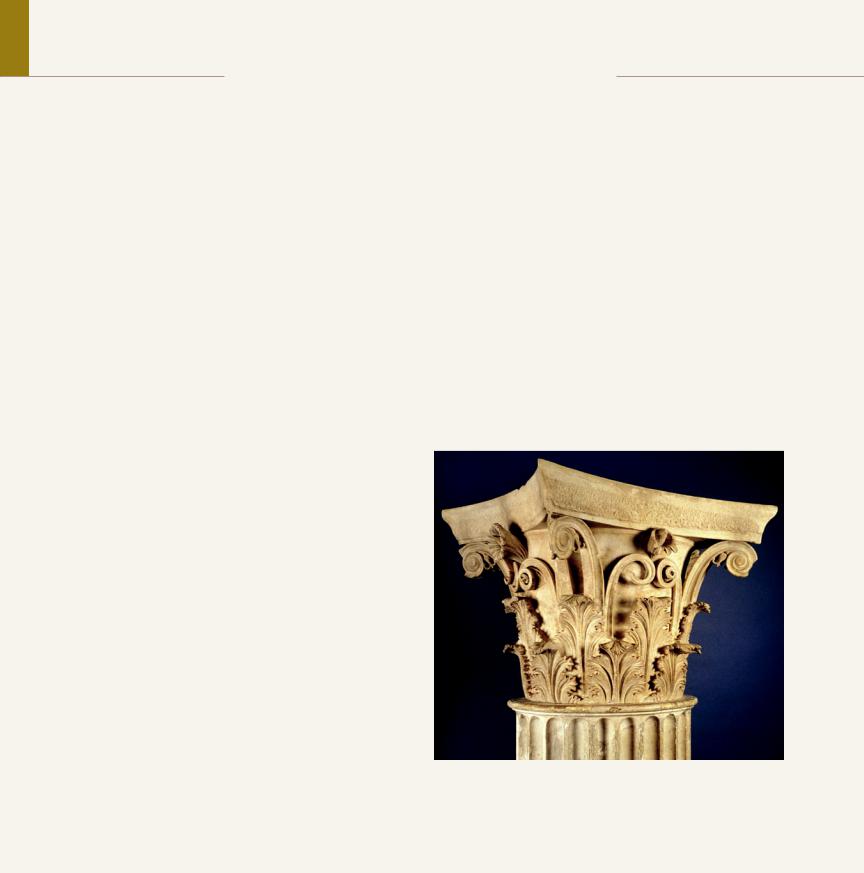

A R C H I T E C T U R A L B A S I C S

The Corinthian Capital

The Corinthian capital (FIG. 5-73) is more ornate than either the Doric or Ionic (FIG. 5-14). It consists of a double row of acanthus leaves, from which tendrils and flowers emerge, wrapped around a bell-shaped echinus. Although this capital often is cited as the distinguishing feature of the Corinthian order, in strict terms no such order exists. Architects simply substituted the new capital type for the

volute capital in the Ionic order.

The sculptor Kallimachos invented the Corinthian capital during the second half of the fifth century BCE. Vitruvius recorded the circumstances that supposedly led to its creation:

A maiden who was a citizen of Corinth . . . died. After her funeral, her nurse collected the goblets in which the maiden had taken delight while she was alive, and after putting them together in a basket, she took them to the grave monument and put them on top of it. In order that they should remain in place for a long time, she covered them with a tile. Now it happened that this basket was placed over the root of an acanthus. As time went on the acanthus root, pressed down in the middle by the weight, sent forth, when it was about springtime, leaves and stalks; its stalks growing up along the sides of the basket and being pressed out from the angles because of the weight of the tile, were forced to form volute-like curves at their extremities. At this point, Kallimachos happened to be going by and noticed the basket with this gentle growth of leaves around it. Delighted with the order and the novelty of the form, he made columns using it as his model and established a canon of proportions for it.*

Kallimachos worked on the Acropolis in Pericles’ great building program. Many scholars believe that a Corinthian column supported the outstretched right hand of Phidias’s Athena Parthenos (FIG. 5-46) because some of the Roman copies of the lost statue include a Corinthian column. In any case, the earliest preserved Corinthian capital dates to the time of Kallimachos. The new type was rarely used before the mid-fourth century BCE, however, and did not become popular until Hellenistic and especially Roman times. Later architects favored the Corinthian capital because of its ornate character and because it eliminated certain problems of both the Doric and Ionic orders.

The Ionic capital, unlike the Doric, has two distinct profiles— the front and back (with the volutes) and the sides. The volutes always faced outward on a Greek temple, but architects met with a vexing problem at the corners of their buildings, which had two adjacent “fronts.” They solved the problem by placing volutes on

*Vitruvius, De architectura, 4.1.8–10. Translated by J. J. Pollitt, The Art of Ancient Greece: Sources and Documents (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 193–194.

Corinthian capitals (FIG. 5-73; see “The Corinthian Capital,” above), an invention of the second half of the fifth century BCE.

Consistent with the extremely conservative nature of Greek temple design, architects did not readily embrace the Corinthian capital. Until the second century BCE, Corinthian capitals were employed, as at Delphi and Epidauros, only for the interiors of sacred buildings. The earliest instance of a Corinthian capital on the exterior of a Greek building is the Choragic Monument of Lysikrates

both outer faces of the corner capitals (as on the Erechtheion, FIG. 5-52, and the Temple of Athena Nike, FIG. 5-55), but the solution was an awkward one.

Doric design rules also presented problems for Greek architects at the corners of buildings. The Doric frieze was organized according to three supposedly inflexible rules:

A triglyph must be exactly over the center of each column.

A triglyph must be over the center of each intercolumniation (the space between two columns).

Triglyphs at the corners of the frieze must meet so that no space is left over.

These rules are contradictory, however. If the corner triglyphs must meet, then they cannot be placed over the center of the corner column (FIGS. 5-25, 5-30, and 5-44).

The Corinthian capital eliminated both problems. Because the capital’s four sides have a similar appearance, corner Corinthian capitals do not have to be modified, as do corner Ionic capitals. And because the Ionic frieze is used for the Corinthian “order,” architects do not have to contend with metopes or triglyphs.

5-73 POLYKLEITOS THE YOUNGER, Corinthian capital, from the tholos, Epidauros, Greece, ca. 350 BCE. Archaeological Museum, Epidauros.

Corinthian capitals, invented in the fifth century BCE by the sculptor Kallimachos, are more ornate than Doric and Ionic capitals. They feature a double row of acanthus leaves with tendrils and flowers.

(FIG. 5-74), which is not really a building at all. Lysikrates had sponsored a chorus in a theatrical contest in 334 BCE, and after he won, he erected a monument to commemorate his victory. The monument consists of a cylindrical drum resembling a tholos on a rectangular base. Engaged Corinthian columns adorn the drum of Lysikrates’ monument, and a huge Corinthian capital sits atop the roof. The freestanding capital once supported the victor’s trophy, a bronze tripod (a deep bowl on a tall three-legged stand).

130 Chapter 5 A N C I E N T G R E E C E

5-74 Choragic

Monument of

Lysikrates, Athens,

Greece, 334 BCE.

The first known instance of the use of the Corinthian

capital on the exterior of a building is the monument Lysikrates erected in Athens to commemorate the victory his chorus won in a theatrical contest.

HELLENISTIC PERIOD

Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Near East and Egypt (where the Macedonian king was buried) ushered in a new cultural age that historians and art historians alike call Hellenistic. The Hellenistic period opened with the death of Alexander in 323 BCE and lasted nearly three centuries, until the double suicide of Queen Cleopatra of Egypt and her Roman consort Mark Antony in 30 BCE after their

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dipteral |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

colonnade |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inner shrine |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Courtyard |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oracular |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

room |

|

|||

|

|

N |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

25 5 |

75 |

1000 feet |

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

5 10 |

20 |

|

30 meters |

|

||||||

decisive defeat at the battle of Actium by Antony’s rival Augustus. That year, Augustus made Egypt a province of the Roman Empire.

The cultural centers of the Hellenistic period were the court cities of the Greek kings who succeeded Alexander and divided his far-flung empire among themselves. Chief among them were Antioch in Syria, Alexandria in Egypt, and Pergamon in Asia Minor. An international culture united the Hellenistic world, and its language was Greek. Hellenistic kings became enormously rich on the spoils of the East, priding themselves on their libraries, art collections, scientific enterprises, and skills as critics and connoisseurs, as well as on the learned men they could assemble at their courts. The world of the small, austere, and heroic city-state passed away, as did the power and prestige of its center, Athens. A cosmopolitan (“citizen of the world,” in Greek) civilization, much like today’s, replaced it.

Architecture

The greater variety, complexity, and sophistication of Hellenistic culture called for an architecture on an imperial scale and of wide diversity, something far beyond the requirements of the Classical polis, even beyond that of Athens at the height of its power. Building activity shifted from the old centers on the Greek mainland to the opulent cities of the Hellenistic monarchs in the East.

TEMPLE OF APOLLO, DIDYMA Great scale, a theatrical element of surprise, and a willingness to break the rules of canonical temple design characterize one of the most ambitious temple projects of the Hellenistic period, the Temple of Apollo at Didyma. The Hellenistic temple was built to replace the Archaic temple at the site the Persians had burned down in 494 BCE when they sacked nearby Miletos. Construction began in 313 BCE according to the design of two architects who were natives of the area, PAIONIOS OF EPHESOS and DAPHNIS OF MILETOS. So vast was the undertaking, however, that work on the temple continued off and on for more than 500 years—and still the project was never completed.

The temple was dipteral in plan (FIG. 5-75, left) and had an unusually broad facade of 10 huge Ionic columns almost 65 feet tall. The sides had 21 columns, consistent with the Classical formula for

5-75 PAIONIOS OF EPHESOS and DAPHNIS OF MILETOS, Temple of

Apollo, Didyma, Turkey, begun 313 BCE. Plan (left) and aerial view (right).

This unusual Hellenistic temple was hypaethral (open to the sky) and featured a double peripteral (dipteral) colonnade with a smaller temple inside the interior courtyard of the larger temple.

Hellenistic Per iod |

131 |

5-76 Restored view of the city of Priene, Turkey, fourth century BCE and later (John Burge).

Despite its irregular terrain, Priene had a strict grid plan conforming to the principles of Hippodamos of Miletos, whom Aristotle singled out as the father of rational city planning.

perfect proportions used for the Parthenon—21 = (2 10) 1—but nothing else about the design is Classical. One anomaly immediately apparent to anyone who approached the building was that it had no pediment and no roof—it was hypaethral, or open to the sky. Also, the grand doorway to what should be the temple’s cella was elevated nearly five feet off the ground so that it could not be entered. The explanation for these peculiarities is that the doorway served rather as a kind of stage where the oracle of Apollo could be announced to those assembled in front of the temple. The unroofed dipteral colonnade was really only an elaborate frame for a central courtyard (FIG. 5-75, right) with a small prostyle shrine containing a statue of Apollo. Entrance to the interior court was through two smaller doorways to the left and right of the great portal and down two narrow vaulted tunnels that could accommodate only a single file of people. From these dark and mysterious lateral passageways, worshipers emerged into the clear light of the courtyard, which also had a sacred spring and laurel trees in honor of Apollo. Opposite Apollo’s inner temple, a stairway some 50 feet wide rose majestically toward three portals leading into the oracular room that also opened onto the front of the temple. This complex spatial planning marked a sharp departure from Classical Greek architecture, which stressed a building’s exterior almost as a work of sculpture and left its interior relatively undeveloped.

HIPPODAMOS OF MILETOS When the Persians were fi- nally expelled from Asia Minor in 479 BCE, the Greek cities there were in near ruin. Reconstruction of Miletos began after 466 BCE according to a plan laid out by Hippodamos of Miletos, whom Aristotle singled out as the father of rational city planning. Hippodamos imposed a strict grid plan on the site, regardless of the terrain, so that all streets met at right angles. Such orthogonal plans actually predate Hippodamos, not only in Archaic Greece and Etruscan Italy but also in the ancient Near East and Egypt. But Hippodamos was so famous that his name has ever since been synonymous with such urban plans. The so-called Hippodamian plan also designated separate quarters for public, private, and religious functions. A “Hippodamian city” was logically as well as regularly planned. This desire to impose order on nature and to assign a proper place in the whole to each of the city’s constituent parts was very much in keeping with the philosophical tenets of the fifth century BCE. Hippodamos’s formula for the ideal city was another manifestation of the same outlook that produced Polykleitos’s Canon and Iktinos’s Parthenon.

132 Chapter 5 A N C I E N T G R E E C E

PRIENE Hippodamian planning was still the norm in Late Classical and Hellenistic Greece. The city of Priene (FIG. 5-76), also in Asia Minor, was laid out during the fourth century BCE. It had fewer than 5,000 inhabitants (Hippodamos thought 10,000 was the ideal number). Situated on sloping ground, many of its narrow northsouth streets were little more than long stairways. Uniformly sized city blocks, the standard planning unit, were nonetheless imposed on the irregular terrain. More than one unit was reserved for major structures such as the Temple of Athena and the theater. The central agora was allotted six blocks.

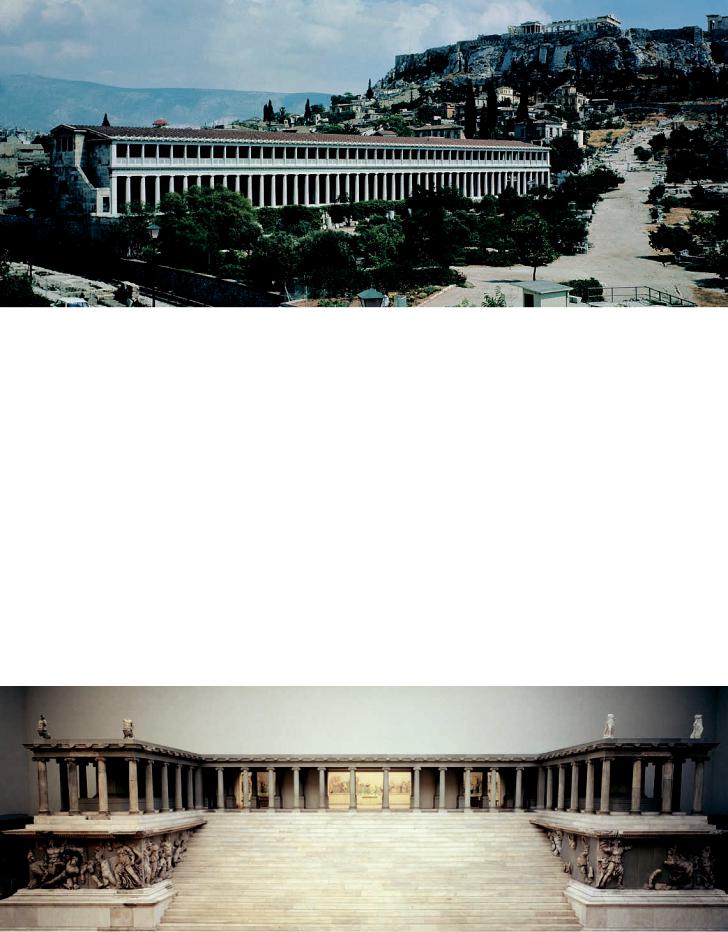

STOA OF ATTALOS, ATHENS Priene’s agora was bordered by stoas. These covered colonnades, or porticos, which often housed shops and civic offices, were ideal vehicles for shaping urban spaces, and they were staples of Hellenistic cities. Even the agora of Athens, an ancient city notable for its haphazard, unplanned development, was eventually framed to the east and south by stoas placed at right angles to one another. These new porticos joined the famous Painted Stoa (see page 121), where the Hellenistic philosopher Zeno and his successors taught. The Stoic school of Greek philosophy took its name from that building.

The finest of the new Athenian stoas was the Stoa of Attalos II (FIG. 5-77), a gift to the city by a grateful alumnus, the king of Pergamon, who had studied at Athens in his youth. The stoa was meticulously reconstructed under the direction of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens and today has a second life as a museum housing more than seven decades of finds from the Athenian agora, as well as the offices of the American excavation team. The stoa has two stories, each with 21 shops opening onto the colonnade. The facade columns are Doric on the ground level and Ionic on the second story. The mixing of the two orders on a single facade had occurred even in the Late Classical period. But it became increasingly common in the Hellenistic period, when architects showed greatly diminished respect for the old rules of Greek architecture, and a desire for variety and decorative effects often prevailed. Practical considerations also governed the form of the Stoa of Attalos. The columns are far more widely spaced than in Greek temple architecture, to allow for easy access. And the builders left the lower third of every Doric column shaft unfluted to guard against damage from constant traffic.

5-77 Stoa of Attalos II, Agora, Athens, Greece, ca. 150 BCE (with the Acropolis in the background).

The Stoa of Attalos II in the Athenian agora has been meticulously restored. Greek stoas were covered colonnades that housed shops and civic offices. They were also ideal vehicles for shaping urban spaces.

Pergamon

Pergamon, the kingdom of Attalos II (r. 159–138 BCE), was one of those born in the early third century BCE after the breakup of Alexander’s empire. Founded by Philetairos, the Pergamene kingdom embraced almost all of western and southern Asia Minor. Upon the death in 133 BCE of its last king, Attalos III (r. 138– 133 BCE), Pergamon was bequeathed to Rome, which by then was the greatest power in the Mediterranean world. The Attalids enjoyed immense wealth, and much of it was expended on embellishing their capital city, especially its acropolis. Located there were the royal palace, an arsenal and barracks, a great library and theater, an agora, and the sacred precincts of Athena and Zeus.

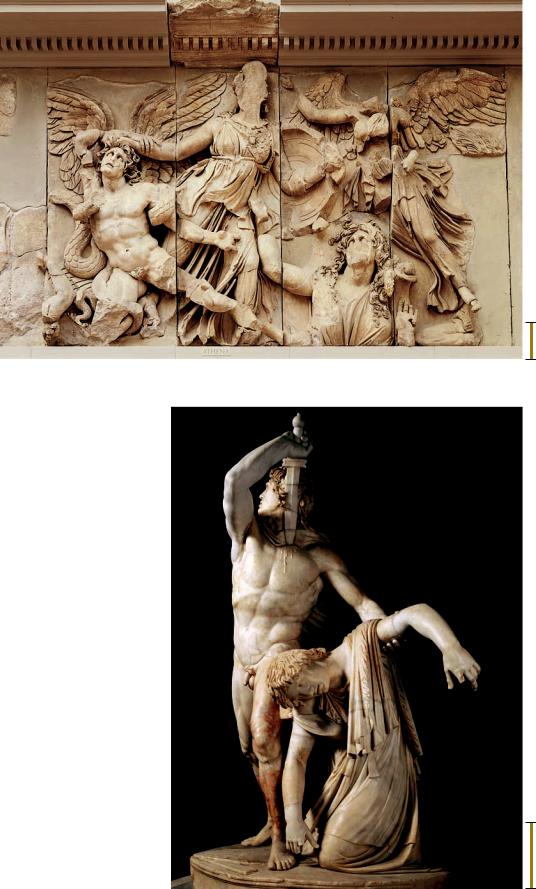

ALTAR OF ZEUS, PERGAMON The Altar of Zeus at Pergamon, erected about 175 BCE, is the most famous Hellenistic sculp-

tural ensemble. The monument’s west front (FIG. 5-78) has been reconstructed in Berlin. The altar proper was on an elevated platform and framed by an Ionic stoalike colonnade with projecting wings on either side of a broad central staircase. All around the altar platform was a sculpted frieze almost 400 feet long, populated by about a hundred larger-than-life-size figures. The subject is the battle of Zeus and the gods against the giants. It is the most extensive representation Greek artists ever attempted of that epic conflict for control of the world. A similar subject appeared on the shield of Phidias’s Athena Parthenos and on some of the Parthenon metopes, where the Athenians wished to draw a parallel between the defeat of the giants and the defeat of the Persians. In the third century BCE, King Attalos I (r. 241–197 BCE) had successfully turned back an invasion of the Gauls in Asia Minor. The gigantomachy of the Altar of Zeus alluded to that Pergamene victory over those barbarians.

5-78 Reconstructed west front of the Altar of Zeus, Pergamon, Turkey, ca. 175 BCE. Staatliche Museen, Berlin.

The gigantomachy frieze of Pergamon’s monumental Altar of Zeus is almost 400 feet long. The battle of gods and giants alluded to the victory of King Attalos I over the Gauls of Asia Minor.

Hellenistic Per iod |

133 |

5-79 Athena battling Alkyoneos, detail of the gigantomachy frieze, from the Altar of Zeus, Pergamon, Turkey, ca. 175 BCE. Marble,

7 6 high. Staatliche Museen,

Berlin.

The tumultuous battle scenes of the Pergamon altar have an emotional power unparalleled in earlier Greek art. Violent movement, swirling draperies, and vivid depictions

of suffering fill the frieze.

1 ft.

A deliberate connection was also made with Athens, whose earlier defeat of the Persians was by then legendary, and with the Parthenon, which already was recognized as a Classical monument— in both senses of the word. The figure of Athena (FIG. 5-79), for example, is a variation of the Athena from the Parthenon’s east pediment. While Ge, the earth goddess and mother of all the giants, emerges from the ground and looks on with horror, Athena grabs the hair of the giant Alkyoneos as Nike flies in to crown her. Zeus himself (not illustrated) was based on the Poseidon of the west pediment. But the Pergamene frieze is not a dry series of borrowed motifs. On the contrary, its tumultuous narrative has an emotional intensity that has no parallel in earlier sculpture. The battle rages everywhere, even up and down the very steps one must ascend to reach Zeus’s altar (FIG. 5-78). Violent movement, swirling draperies, and vivid depictions of death and suffering are the norm. Wounded figures writhe in pain, and their faces reveal their anguish. When Zeus hurls his thunderbolt, one can almost hear the thunderclap. Deep carving creates dark shadows. The figures project from the background like bursts of light. These features have been justly termed “baroque” and reappear in 17th-century European sculpture (see Chapter 19). One can hardly imagine a greater contrast than between the Pergamene gigantomachy frieze and that of the Archaic Siphnian Treasury (FIG. 5-19) at Delphi.

DYING GAULS On the Altar of Zeus, sculptors presented the victory of Attalos I over the Gauls in mythological disguise. An earlier Pergamene statuary group explicitly represented the defeat of the barbarians. Roman copies of some of these figures survive. The sculptor carefully studied and reproduced the distinctive features of the foreign Gauls, most notably their long, bushy hair and mustaches and the torques (neck bands) they frequently wore. The Pergamene victors were apparently not included in the group. The viewer saw only their foes and their noble and moving response to defeat.

In what was probably the centerpiece of the Attalid group, a heroic Gallic chieftain (FIG. 5-80) defiantly drives a sword into his own chest just below the collarbone, preferring suicide to surrender. He already has taken the life of his wife, who, if captured, would have been sold as a slave. In the best Lysippan tradition, the group can be fully appreci-

1 ft.

5-80 EPIGONOS(?), Gallic chieftain killing himself and his wife. Roman marble copy of a bronze original of ca. 230–220 BCE, 6 11 high.

Museo Nazionale Romano–Palazzo Altemps, Rome.

The defeat of the Gauls was also the subject of Pergamene statuary groups. The centerpiece of one group was a Gallic chieftain committing suicide after taking his wife’s life. He preferred death to surrender.

134 Chapter 5 A N C I E N T G R E E C E