PC Recording Studios for Dummies (Jeff Strong)

.pdf

312 Part V: Playing with Plug-Ins

4.Choose either the 1-Band EQ II or 4-Band EQ II option.

Your chosen EQ plug-in window opens. (The 1-Band EQ II option lets you set one EQ parameter, whereas the 4-Band EQ II option lets you work with four parameters. For more on which option would work best for you, check out the following section.)

5.Adjust the parameters that you want to EQ.

You can find the particulars for each kind of EQ — parametric, low-shelf/ high-shelf, and low-pass/high-pass — later in the chapter.

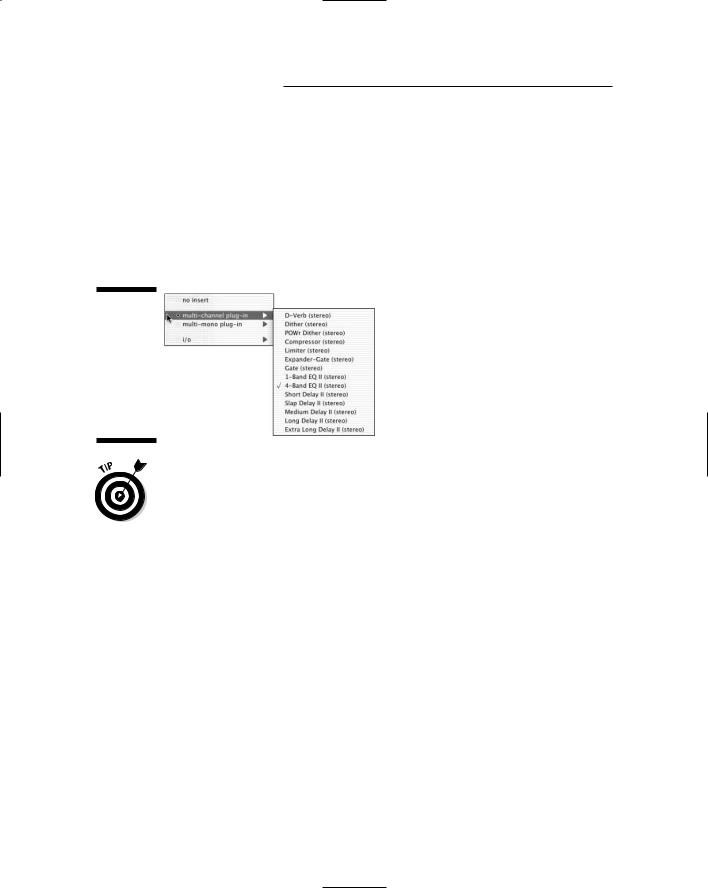

Figure 16-1:

Open the Inserts popup menu and choose the EQ plugin to insert into your track.

If you want to EQ a bunch of tracks in Pro Tools at the same time and use the same settings (submixes, for example), you can do this the following way:

1.Select one of the buses (the path that the Sends use to route a signal) from the Output selector in each track that you want to submix.

2.Choose File New Track.

The New Track dialog box appears.

3.Use the drop-down lists to enter the number of tracks that you want (1), the type (Auxiliary Input), and whether you want your track in stereo.

4.Use your new track’s Input selector to select the bus that you used for the output of the submix tracks as the input for this auxiliary track.

5.Insert one of the EQ plug-ins from the Insert pop-up menu in this auxiliary track.

The EQ Plug-In window opens.

6.Adjust the EQ settings to get the sound that you want.

You can find the particulars for each kind of EQ — parametric, low-shelf/ high-shelf, and low-pass/high-pass — later in the chapter.

TEAM LinG - Live, Informative, Non-cost and Genuine !

Chapter 16: Using Equalization 313

Examining EQ options

Using an EQ in computer-based audio recording programs consists of selecting one of the plug-ins, inserting it into the track that you want to affect, and then setting your parameters. Most programs come with a nice selection of EQ plug-in options. The most useful are multiband EQ, such as the 4-band EQ in Pro Tools (see Figure 16-2) and the Channel EQ in Logic (shown in Figure 16-3). As its name suggests, multiband EQ lets you apply different levels of equalization to specific frequencies, and is really great if you have to tweak your bass guitar so that it doesn’t get lost behind the kick drum, for example.

All audio programs allow you to use third-party EQ plug-ins as long as they are in the supported format (Pro Tools uses RTAS, and Logic uses AU; Chapter 15 has more on these format types), but any such plug-ins have to be purchased separately. If you do an Internet search with the keywords RTAS plug-ins (Pro Tools) or AU Plug-ins (Logic), you’re sure to find tons to choose from.

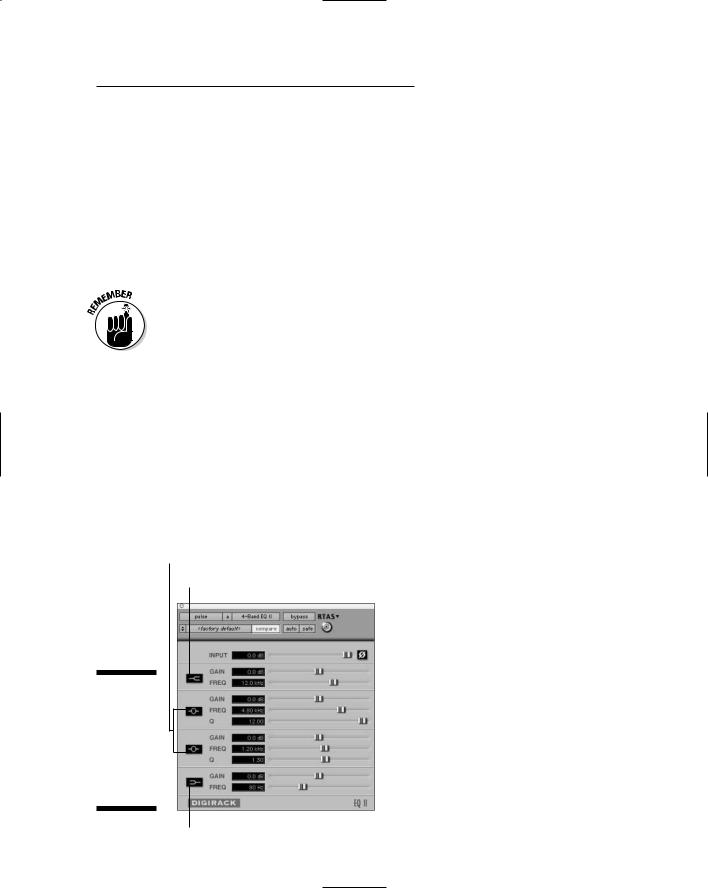

Pro Tools’ 4-band EQ

The 4-band EQ in Pro Tools, shown in Figure 16-2, lets you adjust up to four EQ filters to a track. This type of EQ is useful when you have to do some major EQing to a track. You can choose from a low-shelf, a high-shelf, and two parametric (Peak) EQs.

In the 4-Band EQ Plug-In window, the high-shelf is located at the top of the window and the low-shelf at the bottom. The two parametric EQs are located between the two shelf EQs.

Parametric

High-Shelf

Figure 16-2:

The 4-band EQ in Pro Tools lets you apply four EQ filters to a track.

Low-Shelf

TEAM LinG - Live, Informative, Non-cost and Genuine !

314 Part V: Playing with Plug-Ins

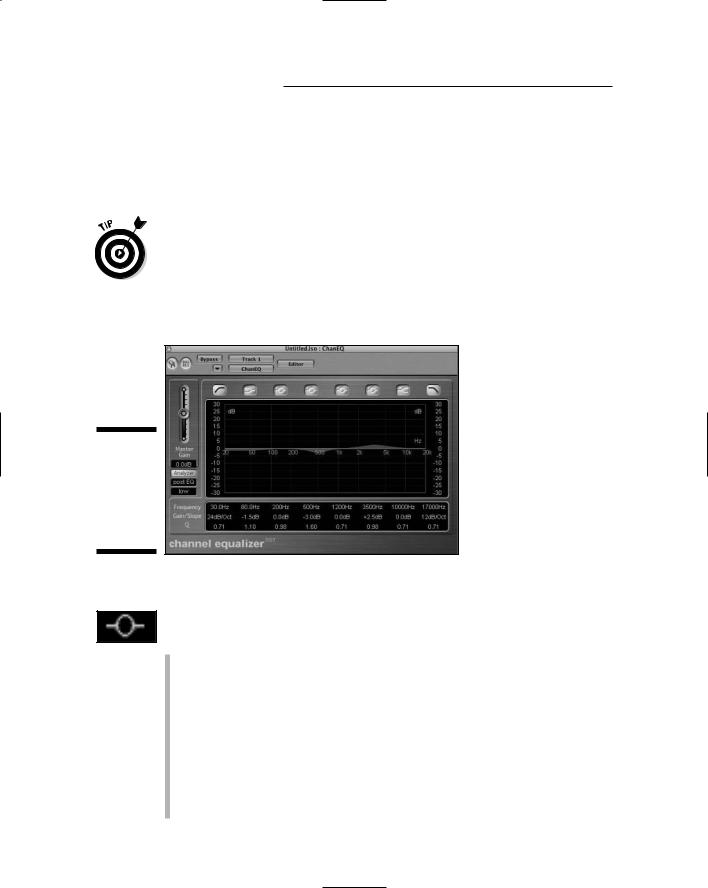

Logic’s Channel EQ

Logic’s Channel EQ is an 8-band EQ with four parametric bands, one highshelf EQ, one low-shelf EQ, one high-pass filter, and one low-pass filter. As you can see in Figure 16-3, the EQ types are listed at the top of the graph, but the adjustments for these bands are located under the main graph.

Logic’s EQ has a really great feature where you can see the frequency response of your track. This function is engaged by clicking the Analyzer button on the left side of the plug-in window. This is handy because, with the Analyzer button engaged, you can actually see the changes you’re making to your track as you make them. This is also a potential problem because many people rely on their eyes instead of their ears. Be careful not to let what you see affect what you hear.

Figure 16-3:

The Channel EQ in Logic lets you apply four EQ filters to a track.

Using parametric EQ

To use the parametric EQ, click the Peak EQ button in the EQ plug-in window you have open. You have three settings to adjust:

Gain: This is the amount of boost (increase) or cut (decrease) that you apply to the signal. In Pro Tools, you can either type in the amount in the text box next to the Peak EQ button or use the slider to the right. In Logic, to get your boost (gain) amount, you can either point your mouse over the parameter and click and drag up or down or you can click in the EQ graph above the parameter controls and drag up or down.

Freq: This frequency is the center of the EQ. You select the range of frequencies above and below this point by using the Q setting (see next bullet). In Pro Tools, you can either type the frequency in the text box on the left or you can use the slider to make your adjustment. In Logic, to get the desired frequency you can either point your mouse over the

TEAM LinG - Live, Informative, Non-cost and Genuine !

Chapter 16: Using Equalization 315

parameter and click and drag up or down or you can click in the EQ graph above the parameter controls and drag left or right.

Q: This is the range of frequencies that your EQ will affect. The higher the number, the narrower the range that gets EQed. In Pro Tools, you adjust this setting either by moving the slider or by clicking in the text box and typing a value between 0.33 and 12. In Logic, you can point your mouse over the parameter and click and drag up or down to get the Q value you want. Your settings can be anywhere from 0.10 to 100.

Using low-shelf/high-shelf EQ

To use low-shelf/high-shelf EQ, click the Low Shelf and High Shelf buttons in the EQ plug-in window. When you use low-shelf/high-shelf EQ, you have two parameters to adjust in Pro Tools and three on Logic:

Gain: This is the amount of boost or cut that you apply to the signal. In Pro Tools, you can either type in the amount in the text box next to the shelf button or use the slider to the right. In Logic, to set the boost (gain) you can either point your mouse over the parameter and click and drag up or down or you can click in the EQ graph above the parameter controls and drag up or down.

Freq: This is the starting frequency for the shelf. In Pro Tools, you can either type in the frequency in the text box or use the slider to make your adjustment. In Logic, to set your desired frequency you can either point your mouse over the parameter and click and drag up or down or you can click in the EQ graph above the parameter controls and drag left or right.

Q: This is the steepness of your EQ’s shelf in Logic. (Pro Tools doesn’t have this option.) The higher the number, the steeper the shelf that’s applied — meaning that you have a narrower range of frequencies that are affected to create the gain change of the shelf. To adjust this parameter, you can point your mouse over the parameter and click and drag up or down to get the Q value you want. Your settings can be anywhere from 0.10 to 2.

Using low-pass/high-pass EQ

Here’s where you tell your plug-in which frequencies to avoid in the course of adjusting the EQ. The lowand high-pass buttons appear in the margin.

To use the lowor high-pass filter, click the appropriate button in the EQ window. In Pro Tools, the only option to set is Freq, which is the frequency that the filter begins filtering. Any frequency below (high-pass) or above (lowpass) the setting is removed from the track. You can either type the frequency in the text box or use the slider to make your adjustment.

TEAM LinG - Live, Informative, Non-cost and Genuine !

316 Part V: Playing with Plug-Ins

In Logic, you have the same three settings — frequency, gain/slope, and Q — as the rest of the EQ types. And as with the other EQ types, you adjust the settings by pointing your mouse over the column of the setting and clicking and dragging the parameter that you want to adjust. With the high-pass and lowpass EQ (filters), the gain/slope parameter adjusts the slope of the filter — how quickly it totally cuts off the frequency.

Equalizing Your Tracks

Only so many frequencies are available for all the instruments in a mix. If multiple instruments occupy a particular frequency range, they can get in each other’s way and muddy the mix. Your goals when EQing during the mixing process are to reduce the frequencies that add clutter and/or to enhance the frequencies that define an instrument’s sound. To do this, make a little space for each instrument within the same general frequency range, which you can accomplish by EQing the individual tracks as you mix. The first part of this chapter shows you how to get up to the point of doing some EQing. The rest of the chapter gets your hands dirty with some real EQing experience.

Here’s a good trick to use when initially trying to decide which frequencies to boost or cut: First, solo the track(s) that you’re working on and set your parametric EQ to a narrow Q setting (a high number). Next, turn the boost all the way up (move the Gain slider all the way to the right) and sweep the frequency setting as you listen. (To sweep, just move the Freq slider to the left and right.) Noticing the areas where the annoying or pleasing sounds are located can help you better understand the frequencies that your instrument produces. When you find a frequency to adjust, experiment with the Q setting to find the range that produces the best sound, and then adjust the amount of boost or cut until it has the effect that you want.

After you determine the frequencies that you want to work with, do your EQing to the individual track while the instrument is in the mix (not soloed). You want to make the instrument fit as well as possible with the rest of the instruments, and to do this you need to know how your instrument sounds in relation to all the music going on around it.

Your goal when making adjustments in EQ is to make all the tracks blend together as well as possible. In some instances, you might have to make some radical EQ moves. Don’t be afraid to do whatever it takes to make your mix sound good — even if it means having cuts or boosts as great as 12dB or more.

TEAM LinG - Live, Informative, Non-cost and Genuine !

Chapter 16: Using Equalization 317

General guidelines

Although some instruments do call for specific EQ guidelines, you need to think about some general considerations when EQing, regardless of the instrument involved. When it comes to the audible frequency spectrum (which is about 20 Hz to 20 kHz), certain frequencies have special characteristics:

Frequencies below 100 Hz can either warm up an instrument or add boominess to it.

Frequencies between 100 and 200 Hz can be muddy for some instruments and can add fullness to others.

Frequencies around 400 Hz can sound boxy.

Frequencies around 800 Hz can add depth or body.

The 1-kHz to 2-kHz frequencies can add attack (initial signal) or punch (pronounced attack) to some instruments and can create a nasally sound in others.

Frequencies from 2 kHz to 5 kHz can increase the presence of instruments.

Frequencies of 5 kHz to 8 kHz can sound harsh on some instruments.

Frequencies from 8 kHz to 17 kHz add airiness or brightness to an instrument.

You’re generally better off cutting a frequency than boosting one. This belief goes back to the days of analog EQs, which often added noise when boosting a signal. This can still be a factor with some digital EQs, but the issue is much less. Out of habit, I still try to cut frequencies before I boost them, and I recommend that you do the same (not out of habit, of course, but because if a noise difference exists between cutting and boosting, you might as well avoid it).

The exact frequencies that you end up cutting or boosting depend on three factors: the sound you’re after, the tonal characteristic of the instrument, and the relationship between all the instruments in the song. In the following sections, I list a variety of frequencies to cut or boost for each instrument. If you don’t want to follow all the suggestions, choose only the ones that fit with your goals.

Use parametric EQ when you’re trying to get your tracks to fit together. Parametric EQ gives you the greatest control over the range of frequencies you can adjust. You can often successfully use the other EQ types (high-shelf, low-shelf, high-pass, low-pass) for the top or bottom frequencies that I list in the following sections.

TEAM LinG - Live, Informative, Non-cost and Genuine !

318 Part V: Playing with Plug-Ins

To adjust frequencies by using Pro Tool’s EQ plug-ins, use the Frequency slider to choose the frequency you want to EQ and the Gain slider to control the amount of EQ that you boost (move the slider to the right) or cut (move the slider to the left) from your track. In Logic, you can point your cursor the frequency in the graphic section of the EQ window and click and drag up or down to adjust the gain.

Vocals

For the majority of popular music, the vocals are the most important instrument in the song. You need to hear them clearly, and they should contain the character of the singer’s voice and style. One of the most common mistakes in mixing vocals is to make them too loud. The next most common mistake is to make them too quiet. (The second mistake most often occurs when a shy or self-conscious vocalist is doing the mixing.) You want the lead vocals to shine through, but you don’t want them to overpower the other instruments. The best way to do this is to EQ the vocal tracks so they can sit nicely in the mix and still be heard clearly. The following guidelines can help you do this.

Lead

The lead vocal can go a lot of ways, depending on the singer and the style of music. For the most part, I tend to cut a little around 200 Hz and add a couple decibels at 3 kHz and again at 10 kHz. In general, follow these guidelines:

To add fullness, add a few decibels at 150 Hz.

To get rid of muddiness, cut a few decibels at 200 to 250 Hz.

To add clarity, boost a little at 3 kHz.

For more presence, add at 5 kHz.

To add air or to brighten, boost at 10 kHz.

To get rid of sibilance, cut a little between 7.5 and 10 kHz.

Backup

To keep backup vocals from competing with lead vocals, cut the backup vocals a little in the low end (below 250 Hz) and at the 2.5- to 3.5-kHz range. To add clarity, boost a little around 10 kHz without letting it get in the way of the lead vocal.

Guitar

For the most part, you want to avoid getting a muddy guitar sound and make sure that the guitar attack comes through in the mix.

TEAM LinG - Live, Informative, Non-cost and Genuine !

Chapter 16: Using Equalization 319

Electric

Electric guitars often need a little cutting below 100 Hz to get rid of muddiness. A boost between 120 and 250 Hz adds warmth. A boost in the 2.5- to 4-kHz range brings out the attack of the guitar, and a boost at 5 kHz can add some bite.

Acoustic

Acoustic guitars often do well with a little cut below 80 Hz and again around 800 Hz to 1 kHz. If you want a warmer tone and more body, try boosting a little around 150 to 250 Hz. Also, try adding a few decibels around 3 to 5 kHz if you want more attack or punch. A few decibels added at 7 kHz can add a little more brightness to the instrument.

Bass

This instrument can get muddy pretty fast. The mud generally happens in the 200to 300-Hz range, so I either leave that alone or cut just a little if the bass lacks definition. I rarely add any frequencies below 100 Hz. If the instrument sounds flat or thin, I boost some between 100 and 200 Hz. Adding a little between 500 Hz and 1 kHz can increase the punch, and a boost between 2.5 and 5 kHz accentuates the attack, adding a little brightness to the bass.

One of the most important things to keep in mind with the bass guitar is to make sure that it and the kick drum can both be heard. You need to adjust the frequencies of these two instruments to make room for both. If you add a frequency to the kick drum, try cutting the same frequency from the bass.

Drums

The guidelines for EQing the drums depend on whether you use live acoustic drums or a drum machine. (The drum machine probably requires less EQ because the sounds were already EQed when they were created.) The type and placement of your mic or mics also affects how you EQ the drums. (You can find out more about mic placement in Chapter 9.)

Kick

You want the kick drum to blend with the bass guitar. To do this, reduce the frequencies that the bass guitar takes up. For example, if I boost a few decibels between 100 and 200 Hz for the bass guitar, I generally cut them in the kick drum (and maybe go as high as 250 Hz). To bring out the bottom end of the kick drum, I sometimes add a couple of decibels between 80 and 100 Hz. The kick drum can get boxy sounding (you know, like a cardboard box), so I

TEAM LinG - Live, Informative, Non-cost and Genuine !

320 Part V: Playing with Plug-Ins

often cut a little between 400 and 600 Hz to get rid of the boxiness. To bring out the click from the beater hitting the head, try adding a little between 2.5 and 5 kHz. This increases the attack of the drum and gives it more presence.

Snare

The snare drum drives the music, making it the most important drum in popular music. As such, it needs to really cut through the rest of the instruments. Although the adjustments that you make depend on the pitch and size of the drum and whether you used one mic or two during recording, you can usually boost a little at 100 to 150 Hz for added warmth. You can also try boosting at 250 Hz to add some depth. If the drum sounds too boxy, try cutting at 800 Hz to 1 kHz. A little boost at around 3 to 5 kHz increases the attack, and an increase in the 8- to 10-kHz range can add crispness to the drum.

If you used two mics during recording, you might consider dropping a few decibels on the top mic in both the 800-Hz to 1-kHz range and the 8- to 10-kHz range. Allow the bottom mic to create the crispness. I generally use a shelf EQ to roll off the bottom end of the bottom mic below, say, 250 to 300 Hz. Depending on the music (R&B and pop, for instance), I might use a shelf EQ to add a little sizzle to the bottom mic by boosting frequencies above 10 kHz.

For many recording engineers and producers, the snare drum sound is almost a signature. If you listen to different artists’ songs from the same producer, you’ll likely hear similarities in the songs’ snare drum sound. Don’t be afraid to take your time getting the snare drum to sound just right. After all, if you become a famous producer, you’ll want people to recognize your distinct snare drum sound. And you want it to sound good anyway.

Tom-toms

Tom-toms come in a large range of sizes and pitches. For mounted toms, you can boost a little around 200 to 250 Hz to add depth to the drum. A boost in the 3- to 5-kHz range can add more of the sticks’ attack, and for some additional presence, try adding a little in the 5- to 8-kHz range. If the drums sound too boxy, try cutting a little in the 600-Hz to 1-kHz range.

For floor toms, you can try boosting the frequency range 40 to 125 Hz if you want to add some richness and fullness. You might also find that cutting in the 400to 800-Hz range can get rid of any boxy sound that the drum might have. To add more attack, boost the 2.5- to 5-kHz range.

Hi-hats

Most of the time, the hi-hats are pretty well represented in the rest of the mics in the drum set, but depending on which mics are picking up the hi-hats, you can use the mics to bring out their sheen or brightness. To do this, try

TEAM LinG - Live, Informative, Non-cost and Genuine !

Chapter 16: Using Equalization 321

boosting the frequencies above 10 kHz with a shelf EQ. You might also find that cutting frequencies below 200 Hz eliminates any rumble created by other drums that the hi-hat mic picked up.

Cymbals

With the cymbals, I usually cut anything below 150 to 200 Hz with a shelf EQ to get rid of any rumbling that these mics pick-up. I also drop a few decibels at 1 to 2 kHz if the cymbals sound kind of trashy or clanky. Adding a shelf EQ above 10 kHz can add a nice sheen to the mix.

Overhead mics

If you used overhead mics to pick up both the drums and the cymbals, be careful about cutting too much from the lower frequencies — doing so just sucks the life right out of your drums. Also, if the drums coming through the overhead mics sound boxy or muddy, work with the 100to 200-Hz frequencies for the muddiness and 400-Hz to 1-kHz frequencies for the boxiness.

Percussion

High-pitched percussion instruments (shakers, for example) sound good when the higher frequencies are boosted a little bit, over 10 kHz for instance. This adds some brightness and softness to their sound. You can also roll off many of the lower frequencies, below 500 Hz, to eliminate any boxiness that might be present from miking too closely. (See Chapter 9 for more on mic placement.)

Lower-pitched percussion instruments, such as maracas, can also have the lower frequencies cut a little — use 250 Hz and lower. Try boosting frequencies between 2.5 and 5 kHz to add more of the instrument’s attack. To brighten them up, add a little bit in the 8- to 10-kHz range.

Piano

For pianos, you often want to make sure that the instrument has both a nice attack and a warm-bodied tone. You can add attack in the 2.5- to 5-kHz range, and warmth can be added in the 80to 150-Hz range. If your piano sounds boomy or muddy, try cutting a little between 200 and 400 Hz.

TEAM LinG - Live, Informative, Non-cost and Genuine !