The Teachers Grammar Book - James Williams

.pdfNOAM CHOMSKY AND GRAMMAR |

169 |

THE BASICS OF TRANSFORMATION RULES

For the time being, let’s set aside the issue of meaning in a theory of language and grammar and turn to the transformation rules themselves. Transformation rules have undergone significant change over the years. Necessarily, this section serves merely as an introduction to some of the rules in Chomsky’s early work. Later in the chapter, we consider the current approach to transformations. Thus, the goal here is to provide some understanding of the general principles of T-G grammar rather than an in-depth analysis.

In Syntactic Structures and Aspects, Chomsky (1957, 1965) proposed a variety of transformation rules, some obligatory and others optional. The rules themselves specify their status. Rather than examining all possible transformation rules, only a few are presented, those that govern some common constructions in English. Before turning to these rules, however, it is important to note that transformations are governed by certain conventions. Two of the more important are the ordering convention and the cycle convention. When a sentence has several transformations, they must be applied in keeping with the order of the rules. In addition, when a sentence has embedded clauses, we must begin applying the transformations in the clause at the lowest level and work our way up. This is the cycle convention. Failure to abide by these conventions when analyzing structure with T-G grammar may result in ungrammatical sentences. What we see in T-G grammar, therefore, is a formalistic model of language production that employs a set of rigid rules that must operate in an equally rigid sequence to produce grammatical sentences.

The Passive Transformation

The relation between actives and passives was an important part of Chomsky’s (1957) critique of phrase-structure grammar, so it is fitting that we examine the rule that governs passives first. Only sentences with transitive verbs can be passivized, and we always have the option of keeping them in the active form, which means that the passive transformation is an optional rule.

Consider sentence 5:

5. Fred bought a ring.

If we change this sentence to the passive form, it becomes:

5a. A ring was bought by Fred.

In keeping with the early version of T-G grammar, sentence 5 represents the deep structure of 5a. The process of the transformation is as follows: First, the

170 |

CHAPTER 5 |

object NP (a ring) shifted to the subject position. Second, the preposition by appeared, and the deep-structure subject (Fred) became the object of the preposition. Third, be and the past participle suffix appeared in the auxiliary, turning the deep structure verb buy into a passive verb form.

The grammar rule represents these changes symbolically. In this rule, the symbol fi means “is transformed into”:

Passive Transformation Rule.

NP1 Aux V NP2 (Fred bought a ring)

fi

NP2 Aux + be -ed/en V by + NP1 (A ring was bought by Fred)

With respect to sentence 5:

NP1 = Fred

NP2 = a ring

V = bought

T-G grammar is predicated on examining the history of a given sentence, and the most effective way of doing so is through tree diagrams, which allow us to examine the deep structure and its corresponding surface structure. The process, however, is different from phrase-structure analysis because it requires a minimum of two trees, one for the deep structure and one for the surface structure. For more complicated sentences, there are more trees, each one reflecting a different transformation and a different stage in the history of the sentence. A convenient guideline is that the number of trees in a T-G analysis will consist of the number of transformations plus one. We can see how this process works by examining sentence 5a on the next page.

Passive Agent Deletion. In many instances, we delete the agent in passive sentences, as in sentence 6:

6. The cake was eaten.

When the subject agent is not identified, we use an indefinite pronoun to fill the slot where it would appear in the deep structure, as in 6a:

6a. [Someone] ate the cake.

This deep structure, however, would result in the surface structure of sentence 6b:

Sentence 5.5a: A ring was bought by Fred.

171

172 |

CHAPTER 5 |

6b. The cake was eaten [by someone].

To account for sentence 6, T-G grammar proposes a deletion rule that eliminates the prepositional phrase containing the subject agent. We can say, therefore, that sentence 6 has undergone two transformations, passive and passive agent deletion. The deletion rule appears as:

Agent Deletion Rule.

NP2 Aux + be -ed/en V by + NP1

fi

NP2 Aux + be -ed/en V

In many cases, passive agent deletion applies when we don’t know the agent of an action or when we do not want to identify an agent. Consider sentences 7 through 10:

7.The plot of the play was developed slowly.

8.The accident occurred when the driver’s forward vision was obstructed.

9.The family was driven into bankruptcy.

10.Buggsy’s favorite goon was attacked.

In sentence 7, we may not know whether the slow plot development should be attributed to the playwright or the director. In 8, the cause of the obstruction may be unknown, but we can imagine a scenario in which someone would not want to attribute causality, owing to the liability involved. Perhaps the obstruction occurred when the driver—a female, say—poked herself in the eye when applying mascara while driving.

APPLYING KEY IDEAS

Directions: Produce diagrams for the following sentences. Remember: T-G grammar requires two trees for any sentence that has undergone transformation.

1.Maria was thrilled by the music in the park.

2.Mrs. DiMarco was stunned by the news.

3.The door was opened slowly.

4.Fred was stung by a swarm of bees.

5.The nest had been stirred up deliberately.

NOAM CHOMSKY AND GRAMMAR |

173 |

Usage Note

Many writing teachers tell students not to use the passive in their work, and they urge students to focus on “active” rather than “passive” verbs. However, teachers usually do not link passive verbs to passive constructions but instead identify them as forms of be, which creates quite a bit of confusion. For example, students who write something like “The day was hot” might find their teacher identifying was as a passive verb—even though it is not in this case—and recommending a revision into something like “The sun broiled the earth.” Of course, this revision entirely changes the meaning of the original, and in some contexts it will be inappropriate. The injunction against passives is meaningful in the belles-lettres tradition that has shaped the critical essay in literature, but it is misplaced in the broader context of writing outside that tradition.

In science and social science, the passive is a well-established and quite reasonable convention. It normally appears in the methods section of scientific papers, where researchers describe the procedures they used in their study and how they collected data. The convention is based on the worthwhile goal of providing an objective account of procedures, one that other researchers can use, if they like, to set up their own, similar study. This objectivity is largely a fiction because anyone reading a scientific paper knows that the authors were the ones who set up the study and collected the data. Nevertheless, the passive creates an air of objectivity by shifting focus away from the researchers as agents and toward the actions: “The data were collected via electrodes leading to three electromyograms.” Moreover, contrary to what some claim, there is nothing insidious about the fiction of objectivity.

The widespread use of passive constructions outside the humanities indicates that blanket injunctions against them are misguided. It is the case, however, that the passive is inappropriate in many situations. Even in a scientific paper, the passive usually appears only in two sections—methods and results. In the introduction and conclusion sections, writers tend to use active constructions. In addition, most school-sponsored writing is journalistic in that it does not address a specific audience of insiders, as a scientific paper or even a lab report does. Journalistic writing by its very nature is written by outsiders for outsiders, and it follows conventions associated with the goals of clarity, conciseness, and generating audience interest. Any writing with these goals will not use passives with much frequency. Quite simply, it is easier for people to process sentences in the active voice with a readily identifiable subject.

Because the passive allows us to delete subject agents, many people use it to avoid assigning responsibility or blame. Sentence 8 on page 172, for example,

174 |

CHAPTER 5 |

came from an automaker’s report on faulty hood latches in a certain line of cars. The driver’s forward vision was obstructed by the hood (subject agent deleted) of his car, which unlatched at 60 miles an hour and wrapped itself around the windshield. The report writers could not include the subject agent without assigning responsibility and potential liability to the company, which they avoided for obvious reasons. Using the passive, with agent deleted, allowed them to describe the circumstances of the accident without attaching blame, which was left to a court to determine.

Industry and government are the primary but not the sole sources of such evasiveness. Passives appear spontaneously in the speech and writing of people who strive, for one reason or another, to be circumspect. The usage question regarding passive constructions, consequently, revolves around situation.

APPLYING KEY IDEAS

Directions: Examine a paper you’ve written for another class and see whether you can find any passive constructions. If you find some, determine whether they are appropriate to that context, given the previous discussion. If they are not appropriate, rewrite them in active form.

RELATIVE CLAUSE FORMATION

Relative clauses generally function as modifiers that supply information about nouns. In addition, they generally allow us to avoid repeating a noun. Consider the following sentences:

11.The message, which Macarena had left near the flowers, baffled Fred.

12.The wallet that held Macarena’s money was in the trunk.

13.The woman whom I love has red hair.

Each of these sentences contains an independent clause and a relative clause. Each relative clause is introduced by a relative pronoun. The respective clauses are shown here:

11a. the message baffled Fred/which Macarena had left near the flowers 12a. the wallet was in the trunk/that held Macarena’s money

13a. the woman has red hair/whom I love

Being able to identify the underlying clauses in a sentence that has a relative clause is an important part of understanding the grammar. On this account, if

NOAM CHOMSKY AND GRAMMAR |

175 |

we consider the deep structure of each sentence, we need to look at the underlying noun phrases that get replaced during relativization. Doing so results in the clause pairs as shown:

11b. the message baffled Fred/Macarena had left the message near the flowers 12b. the wallet was in the trunk/the wallet held Macarena’s money

13b. the woman has red hair/I love the woman

Teaching Tip

Students often find relative clauses confusing. Examining the underlying structure of sentences like those cited helps students recognize the duplicate NPs that must be changed to relative pronouns. It also provides a foundation for discussing sentence combining. Many students tend to write short, choppy sentences of the sort that we would have if we punctuated the clauses in 11b through 13b as independent clauses:

•The message baffled Fred. Macarena had left the message near the flowers.

•The wallet was in the trunk. The wallet held Macarena’s money.

•The woman has red hair. I love the woman.

Showing students how to join these clauses through relativization is a quick and easy way to help them improve their writing. Indeed, as mentioned previously, T-G grammar provided the foundation for sentence combining, a very effective method for teaching students how to increase their sentence variety.

In T-G grammar, relative clauses are generated with the following rule:

Relative Clause Rule

NP1 S[Y NP2 Z]S

fi

NP1 S[wh-pro Y Z]S

RP wh-pro Æ

prep RP

This rule looks more complicated than it is. Y and Z are variables that T-G grammar uses to account for constituents that do not affect the transformation. The important factors are that NP1 must equal NP2 and that there is a clause, represented by S and the brackets, that branches off NP1. The transformation takes NP2 and turns it into a relative pronoun, which is designated as wh-pro because so many relative pronouns begin with the letters wh. In the event that NP2 is the subject of the clause, the variable Y will be empty. In the event that NP2 is the object, Y will be everything in front of the object.

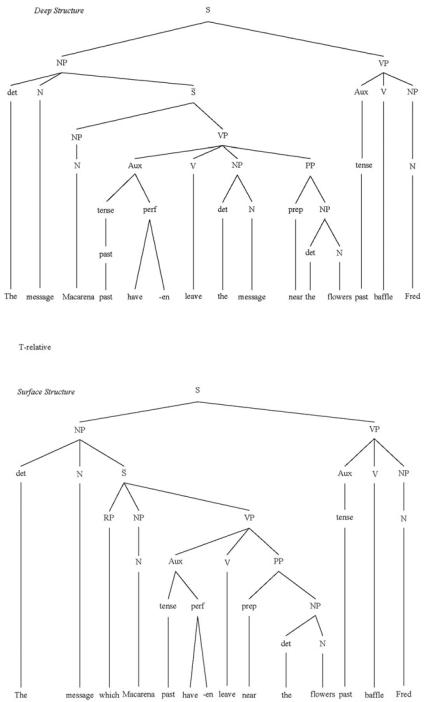

The diagrams 5.11 through 5.13 illustrate how the transformation works.

Sentence 5.11: The message, which Macarena had left near the flowers, baffled Fred.

Sentence 5.11: The message, which Macarena had left near the flowers, baffled Fred. (continued)

176

Sentence 5.12: The wallet that held Macarena’s money was in the trunk.

Sentence 5.12: The wallet that held Macarena’s money was in the trunk. (continued)

177

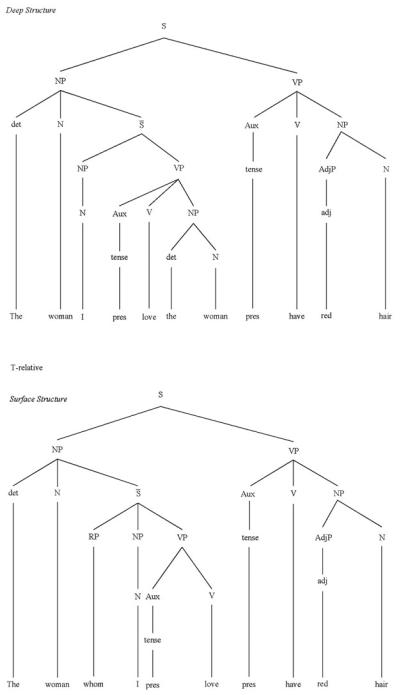

Sentence 5.13: The woman whom I love has red hair.

Sentence 5.13: The woman whom I love has red hair. (continued)

178