The Teachers Grammar Book - James Williams

.pdf

PHRASE STRUCTURE GRAMMAR |

129 |

soon. The use of will in the first person does not express simple future but instead signifies a promised action, as in I will give you the loan. The use of shall in the second and third persons signifies a command, as in You shall stop seeing that horrible woman immediately. Currently, there are only two instances of widespread use of shall in American English, even among Standard speakers: in legal documents and in questions, as in Shall we go now?

Do Support

In English, the word do is used to emphasize a statement, as in these examples:

29.Fred does like the veal.

30.Macarena did deposit the check into her account.

Sentence 4.30: Macarena did deposit the check into her account.

130 |

CHAPTER 4 |

When do is used for emphasis, it is referred to as do support. Do is analyzed as part of the auxiliary. In Standard English, do cannot appear with another modal, although it can in Black English Vernacular. We therefore need to change our rule for the auxiliary once again:

Aux Æ tense (M) (DO)

A diagram of sentence 30 illustrates what our current analysis would look like.

APPLYING KEY IDEAS

Directions: Analyze the following sentences, identifying each of their components.

1.Fred and Macarena drove to the beach.

2.Fritz called Macarena several times.

3.Rita de Luna did return the telephone call.

4.Fritz polished the lenses of the telescope and considered the possibilities.

5.They would be at that special spot near Malibu.

6.Quickly, Fritz made himself a chicken salad sandwich and poured lemonade into the thermos.

7.Fritz could drive to Malibu in 40 minutes from the apartment in Venice.

8.Buggsy must employ a dozen goons.

9.If Buggsy were fully retired, he would become bored.

10.Mrs. DiMarco does forget things sometimes.

11.Someday, he will regret those poor eating habits.

12.If Buggsy were honest, he would turn himself over to the police.

13.They might vacation in Acapulco.

14.She can spend money in some remarkable ways.

15.Fred and Fritz do get jealous of each other.

PROGRESSIVE VERB FORMS

The progressive verb form in English indicates the ongoing nature of an action and is considered to be a feature of aspect. Progressives are formed with be and a verb to which the suffix -ing is attached. Progressive (prog) is analyzed as part of the auxiliary, which means that we need to make another adjustment to our phrase-structure rule:

Aux Æ tense (M) (DO) (prog)

prog Æ be -ing

PHRASE STRUCTURE GRAMMAR |

131 |

This new rule allows us to analyze sentences like the following:

31.Macarena was dancing at China Club.

32.The band members were playing a hot salsa.

33.They are thinking about the next break.

Progressive Verb Forms and Predicate Adjectives

English presents an analytical problem with sentences like the following:

34.Raul was running.

35.His toe was throbbing.

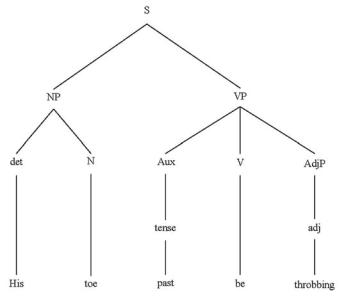

The structure of these sentences seems to be very similar, and, in fact, it may seem reasonable to analyze them both as having progressive form verb phrases. Such an analysis, however, is not accurate. Sentence 34 indeed has a progressive form verb phrase, but sentence 35 does not; instead, the VP consists of a linking verb and a predicate adjective. The tree diagrams for these sentences clearly illustrate the difference between the two sentences.

Sentence 4.34: Raul was running.

132 |

CHAPTER 4 |

Sentence 4.35: His toe was throbbing.

The key to understanding the difference lies in recognizing the distinct roles the two subjects have in these sentences. In sentence 34, the subject is an agent performing an action. In sentence 35, the subject is not an agent, so it does not perform an action, which means that throbbing cannot describe an action in this case because no action is performed. Instead, throbbing provides existential information. On this account, we can say that progressive forms always have an agentive subject. Whenever the subject is not an agent, the verb phrase consists of a linking verb and predicate adjective. This analysis is supported by the structures of sentences like the following:

•Mrs. DiMarco was boring.

•Mrs. DiMarco was boring Raul.

In the first example, Mrs. DiMarco is not an agentive subject, whereas in the second she is. The difference in function not only results in different grammatical analyses but also, as we should expect, in different meanings. Further support comes from the fact that words like throbbing also can function as simple adjectives, as in She had a throbbing headache. Following are some additional examples for illustration:

• Macarena was jogging along the beach. (progressive verb form)

PHRASE STRUCTURE GRAMMAR |

133 |

•The waves were glistening. (predicate adjective)

•Buggsy was watching from the deck of his beach house. (progressive verb form)

•He found that the sight of all the happy people was tiring. (predicate adjective)

PERFECT VERB FORMS

The perfect verb form in English consists of have and a verb to which the past participle suffix -ed/-en has been attached. It signifies more than one temporal relation.

•The past perfect, for example, indicates that one event occurred before another event.

•The present perfect indicates that an event has recurred or that it already has occurred.

•The future perfect indicates that an event will have occurred by the time that another event will be happening.

These three possibilities, respectively, are illustrated in the following sentences:

36.Fred had eaten at Spago many times before that fateful day. (past perfect)

37.Macarena has looked everywhere for the diskette. (present perfect)

38.Fritz will have driven 150 miles before dark. (future perfect)

Like the progressive, the perfect verb form is analyzed as part of the auxiliary; we abbreviate it here as perf . Making the necessary adjustment to the phrase-structure rule results in:

Aux Æ tense (M) (DO) (prog) (perf)

Perf Æ have -ed/-en

POSSESSIVES

English forms the possessive using pronouns or a noun and a possessive (poss) marker, as in her book or Maria’s book. Possessives are considered to be in the category of determiners. To this point, our discussion of determiners has included only articles, but now we need to expand our notion of this grammatical category. We can describe the nature of possessives by using an expression such as the following:

134 |

CHAPTER 4 |

pro |

|

|

|

det Æ NP |

poss |

|

|

art |

|

poss Æ ’s

This analysis shows that a determiner is a pronoun, a noun plus possessive marker, or an article. We can use sentence 39 to analyze the underlying nature of noun possessives:

39. Fred’s shirt had a hole in it.

Most grammatical analyses pay little attention to possessive pronouns for good reason. The problem lies with pronouns. Designating the possessive her as she + poss seems counterintuitive because there is no evidence that her exists as anything other than an independent pronoun. We form the possessive noun by attaching the possessive marker to the noun. Possessive pronouns, however, exist as independent lexical items and are not formed at all—they already exist in the lexicon. Initially, it may seem strange to classify possessive NPs and pronouns as determiners, but they nevertheless do resemble articles. For example, we do not form an by adding n to a; the two forms exist independently. The same holds true for possessive pronouns. Consequently, most analyses exclude possessive pronouns from the domain of the NP and place them in the domain of determiner.

RESTRICTIVE AND NONRESTRICTIVE MODIFICATION

Let’s consider the following sentences:

40.The goon with a gun in his hand stood guard at the entrance.

41.The goon, with a gun in his hand, stood guard at the entrance.

42.Buggsy’s girlfriend Rita loved Porsches.

43.Buggsy’s girlfriend, Rita, loved Porsches.

These sentences are very similar, but at the same time they are quite different. We first notice that the modifiers—with a gun in his hand and Rita—are functioning adjectivally to provide information to the noun phrases The goon and Buggsy’s girlfriend, respectively.2 In sentence 40, we understand that there

2Rita also renames the NP. Nouns that function in this way are often called noun phrase appositives.

PHRASE STRUCTURE GRAMMAR |

135 |

are several goons and that one of them has a gun in his hand. In 41, there is only one goon, and he just happens to have a gun in his hand. A similar situation exists in sentences 42 and 43: In 42, we understand that Buggsy has more than one girlfriend and that the one named Rita loved Porsches; in 43, Buggsy has one girlfriend, she loved Porsches, and her name just happens to be Rita.

What differentiates the sentences in each case is the nature of the modifiers. Note that the PP with a gun in his hand and the NP Rita in sentences 40 and 42, respectively, are not set off with punctuation, whereas in 41 and 43 they are. Moreover, the PP in sentence 40 defines the goon, distinguishing him from others. The same can be said of the NP Rita in sentence 42. In sentences 41 and 43, on the other hand, the modifiers are set off with commas, and they simply supply additional information, not defining information. We use the terms restrictive and nonrestrictive modification to differentiate the two types of structures. Restrictive modifiers provide defining information and are not punctuated. Nonrestrictive modifiers provide nondefining information and are punctuated.

Teaching Tip

Restrictive and nonrestrictive modification is one of the more confusing topics in writing classes. By the time students reach high school, for example, a majority will use nonrestrictive modification when they should use restrictive, and vice versa. We see this most frequently with regard to the titles of literary works, with students regularly producing sentences such as:

•?Steinbeck’s novel, The Grapes of Wrath, was inspired by the wave of socialism that swept America in the 1930s.

The problem here is that Steinbeck wrote several novels, not just one. Because the title is punctuated as a nonrestrictive modifier, the writer communicates that he or she believes otherwise—not a good position to be in if writing for an audience that knows anything at all about John Steinbeck. The correct form is:

•Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes of Wrath was inspired by the wave of socialism that swept America in the 1930s.

Most students have a hard time remembering the terms “restrictive” and “nonrestrictive,” so in many cases it is easier to focus on the role of punctuation. When there is no punctuation around the modifier—when it functions restrictively, in other words—the modifier is defining one among many. When there is punctuation around the modifier—when it functions nonrestrictively—the modifier is nondefining, just supplying additional information, and there is only one. Of course, one needs a certain amount of knowledge in some situations to make this distinction. If a student doesn’t know anything about Steinbeck, determining the correct punctuation is a real problem. But solving the problem offers opportunities for learning.

136 |

CHAPTER 4 |

SUBORDINATE CLAUSES

We discussed subordinate clauses (SC) on pages 86 to 89 and noted that they always begin with a subordinating conjunction. When a sentence contains a subordinate clause (or any other type of dependent clause) it is called a complex sentence. (A sentence with coordinated independent clauses and at least one dependent clause is called a compound-complex sentence.) Some of the more common subordinating conjunctions were listed previously and are shown again here for convenience:

because |

if |

as |

until |

since |

whereas |

although |

though |

while |

unless |

so that |

once |

after |

before |

when |

whenever |

as if |

even if |

in order that |

as soon as |

even though |

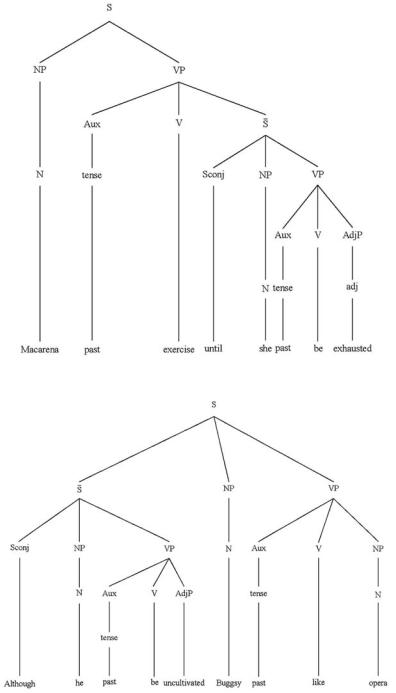

Subordinate clauses function as adverbials; thus, they modify a verb phrase or an entire clause. In the latter case, they are sentence-level modifiers. The difference is related to the restrictive or nonrestrictive nature of the modifier. Let’s examine these two possibilities:

44.Fred drove to Las Vegas because he liked the desert air.

45.Macarena exercised until she was exhausted.

46.Although he was uncultivated, Buggsy liked opera.

47.Fritz wore a sweater, even though the evening was warm.

48.Raul, because he was young, showed the confidence of youth.

In sentences 44 and 45, the SC is a restrictive modifier, which means that it supplies necessary or defining information to a verb phrase. In sentences 46 through 47, however, the subordinate clause is a nonrestrictive modifier in the initial, final, and medial positions, respectively. Nonrestrictive subordinate clauses are sentence-level modifiers. However, some subordinate clauses at the beginning of a sentence may not be punctuated if the writer is using the length convention for initial modifiers. Such initial subordinate

PHRASE STRUCTURE GRAMMAR |

137 |

clauses nevertheless are deemed nonrestrictive. They have to be because as adverbials they must modify either a VP or an S. In the initial position, they can modify only an S.

With certain verbs, subordinate clauses can function as complements, as in:

49.We wondered whether the fish were fresh.

50.They could not decide whether the trip was worth the cost.

In an ideal world, we would be able to write a phrase-structure rule that describes all these structures and that also captures the fact that a subordinate clause functions adverbially as part of the verb phrase or as a sen- tence-level modifier. But there is no way to provide such information in the rule, so we must be satisfied with a rule that just describes the structure; only diagrams can illustrate how the SC functions. Several possibilities exist for rules, but the simplest seems to be one similar to the XP rule we used for coordination. If we think of a dependent clause as S (read bar-S), our rule would be:

XP Æ XP S

S Æ Sconj NP VP

The first expression states that any phrase, XP, can be rewritten as that phrase plus S. S, in turn, can be rewritten as a subordinating conjunction (Sconj), a noun phrase, and a verb phrase. Stated another way, any XP may have a S attached to it. As in the rule for coordination, XP can represent either a clause or a phrase. We must explain outside the rule, as a constraint, that S attaches either to S or VP. We can do this because the grammar is concerned primarily with describing existing sentences. If structuralists had given the grammar a generative component—that is, if it were more concerned with how people generate sentences with subordinate clauses—they might have attempted to develop an expression that addresses the question of placement. Without this concern, the issue is moot because placement is given in the utterance being described.

We want a rule that is very generalizable, of course, so shortly in this chapter we expand the definition of S to include other types of dependent clauses, which means that S attaches to various types of phrases.

A couple of diagrams can make it easier to understand the nature of SC modification. Consider these diagrams for sentences 45 and 46:

Sentence 4.45: Macarena exercised until she was exhausted.

Sentence 4.46: Although he was uncultivated, Buggsy liked opera.

138