Usher Political Economy (Blackwell, 2003)

.pdf382 |

L A W |

the relatives of the victims of murder who might extract justice privately if the law will not act on their behalf. On this view, the death penalty is preferable to long imprisonment even if the number of murders deterred is exactly the same. Execution of murderers on this view is a “good” rather than a “bad,” and imprisonment would only be preferable to the death penalty if imprisonment were a fate worse than death or if imprisonment were the greater deterrent to crime.

Weighting vengeance and deterrence, and ignoring the risk of wrongful conviction, the death penalty would be warranted if

MD + γDGD < MI + γIGI |

(5) |

where GD is the number of people found guilty and executed for murder, GI is the number of people found guilty and imprisoned for murder, γD is one’s degree of concern for the executed murderer, and γI is one’s degree of concern for the imprisoned murderer.

If deterrence were one’s only concern in the design of the law, then γD > γI > 0 on the principle that harm to anybody is deemed unfortunate. If vengeance were one’s only concern in the design of the law, then γD < γI < 0 on the principle that harm inflicted by the state on murderers is per se desirable and that execution is a more fitting retribution than imprisonment. Obviously, GD < MD and GI < MI because the criminal justice system is imperfect.

Some people consider all killing, by the murderer and by the state, as almost equally deplorable. One may see the murderer as an unfortunate by-product of a disturbed childhood in a poorly organized society, or one may have a special abhorrence to killing by the state. Though the hangman does the deed, each citizen is implicated in an execution because he, as voter, commanded the deed to be done. Deterrence would then become the only justification for punishment, and the values of γI and γD would be positive. Other people believe that everyone must take full responsibility for his actions and see the killing of a murderer by the state as appropriate and right, regardless of the consequence for the incidence of murder. Such people see vengeance as the justification for punishment, and their values of γI and γD are negative.

The cost of detection, litigation, and punishment

Just as society buys safety in the construction of roads or the provision of medical care, so too does society buy safety through the criminal justice system. Expenditure on the police reduces the incidence of crime, allowing the streets to be patrolled more carefully and more resources to be devoted to each and every investigation. Expenditure on the judiciary reduces the incidence of crime, allowing prosecutions to be conducted more quickly and more thoroughly, and raising the probability that the criminal will be punished in accordance with the law.

A person’s trade-off between cost and safety is similar to Robinson Crusoe’s tradeoff between bread and cheese in chapter 3. Ignoring both the well-being of the criminal and the wrongful conviction of the innocent, a person’s taste can be represented by indifference curves over two goods, income and the probability of survival, where income (assumed net of the cost of the criminal justice system) is the value at

Income (y)

L A W |

383 |

– |

x |

y |

y

0 |

s |

1 |

Survival probability (s)

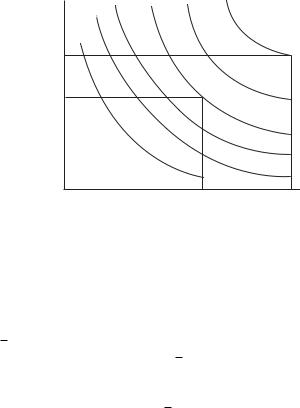

Figure 11.2 A person’s indifference curves for income and probability of survival.

current prices of bread, cheese, and all other goods consumed, where the only threat to survival is murder and where all quantities are per year.

The person’s indifference curves are shown in figure 11.2 with income, y, on the vertical axis and survival probability, s, on the horizontal axis. The point x, with coordinates y and 1, represents the person’s situation as it would be if murder vanished spontaneously. His income would be y and his survival probability would be 1. Otherwise, his net income is y and his survival probability is s, where

y = |

y |

− c |

(6) |

s = 1 − m |

(7) |

||

where c is the cost to that person of the criminal justice system, and m is his probability of being murdered in the course of the year.

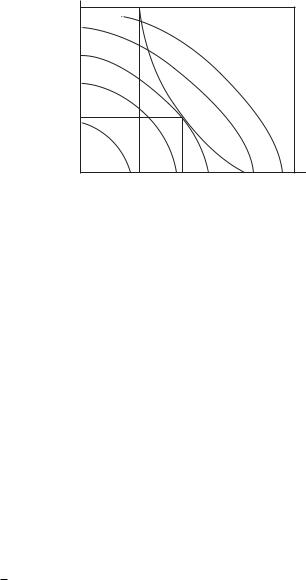

For depicting the cost of crime, it is helpful to reformulate indifference curves with reference to c and m (the cost per person of the criminal justice system and the murder rate) rather than with reference to y and s. That is easily done. Figure 11.3 is a reconstruction of figure 11.2 with indifference curves looked at not from the origin, 0, but upside-down and back-to-front from the point x. The point x in figure 11.3 becomes the mirror image of the point 0 in figure 11.2. By construction, the indifference curves are bowed out rather than bowed in and a person’s welfare increases toward the origin rather than away from it.

The technology of crime prevention can be represented as an extra curve in figure 11.3. This is the dashed curve beginning on the horizontal axis at the point m (the murder rate as it would be if nothing were spent on the criminal justice system and no punishment were ever inflicted by the state) and rising ever more steeply until the entire national income is devoted to crime prevention and the murder rate is reduced to m . Note that m remains greater than 0 because not all murder can be deterred; some murder is inevitably committed no matter how large a share of the nation’s resources is devoted to the prevention of crime. Think of figure 11.3 as

384

|

|

|

y |

|

detection,of litigation |

|

punishment(c = y – y) |

||

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

c*** |

||

Cost |

and |

|||

|

0 |

|

||

L A W

x*

x***

m** |

m*** |

m* |

1 |

murder rate (m = 1 – s) |

|

|

|

Figure 11.3 Indifference curves for the cost of the criminal justice system and the murder rate.

referring to a typical person so that the cost of deterrence to this person and the cost per head to society as a whole are one and the same.

Optimal deterrence is signified by the point x where the “cost of deterrence” curve is just tangent to an indifference curve, the highest (in the sense of making a person as well off as possible) indifference curve attainable with the available technology of crime detection and prosecution. The corresponding expenditure per head on the prevention of murder is c , and the corresponding murder rate is m . The common slope of the indifference curve and the “cost of deterrence” curve at the point x is the typical person’s dollar value of murder prevention, a close relative of the value of life in cost-benefit analysis as discussed in the last chapter. The slope represents the amount of money this person is prepared to pay for a reduction in the murder rate.

When society must choose between the death penalty and imprisonment, each punishment can be represented by a distinct cost of deterrence curve, and each curve is tangent to an indifference curve at a point like x in figure 11.3. The punishments can then be evaluated in accordance with the locations of the corresponding x . The better punishment is whichever brings the person to the “higher” (the closer to the origin) indifference curve. Of course, the locations of the cost of deterrence curves need not remain stationary over time, and, by definition, prosperity increases the average y for society as a whole, so that, as argued above, the better punishment at one time and place need not remain the better punishment everywhere and forever.

Years ago, the cost of execution would have been very much less than the cost of life imprisonment. Today, that is no longer so. The cost of actually putting a person to death may be small by comparison with the cost of keeping a person in prison for the rest of his life, but the full cost of punishment by execution is far greater than the cost of the execution itself. Societies that still impose the death penalty go to enormous effort and expense in litigation to be sure that only the appropriate criminals are executed. Not all murders are alike as we have so far assumed, and the law typically reserves the death penalty for murders that are especially heinous or brutal. Fear of

L A W |

385 |

placing a convicted murderer in the wrong category compounds the fear of mistaken conviction. When Canada had the death penalty, the federal cabinet had to approve each execution, and frequently commuted the sentence to life imprisonment. In the United States, a convicted murderer can expect to spend ten to fifteen years in prison while his appeals to higher courts are being considered, at vast expense to cover the cost of lawyers for the defense, lawyers for the prosecution, the court, and imprisonment while waiting for a final determination. Of course, this extra cost per murderer might be offset by a lower murder rate if the death penalty really were a significantly greater deterrent, a question about which there is no firm consensus in the literature of crime and punishment.

Pulling all this together, a citizen would prefer to punish murder by execution rather than by imprisonment if

[αMD + γDGD + βDWD + CD] < [αMI + γIGI + βIWI + CI] |

(8) |

where the subscripts D and I refer to the death penalty and imprisonment, M is the number of murders committed, G is the number of guilty murderers punished, W is the number of innocent people punished for murder by mistake, C is the dollar value of the cost of detection, conviction, and punishment of murderers, and α, β, and γ are a person’s weights of the different harms associated with murder, all expressed as dollar values so that the weight attached to C is automatically equal to 1.

Society can be thought of as choosing the punishment for murder and arranging the specifics of the criminal justice system to minimize the weighted sum of all four harms of crime, M, G, W, and C. One favors the death penalty if the weighted sum of the four costs is less when murderers are executed than when murderers are imprisoned. The four harms are weighted in equation (8) by supposedly invariant parameters representing the preferences of the citizen. In reality, the weighting would be more complex. Attainable combinations of M, G, W and C would be represented by a function comparable to the dashed curve showing attainable combinations of M and C in figure 11.3. In a community of identical people, all combinations of M, G, W and C, attainable or not, could be represented by multi-dimensional indifference curves. Society’s choice of M, G, W and C would then lie on the highest attainable indifference curve.

Each side of equation (8) is the minimized value of the full social cost of murder when one of the two punishments is in force. The technology of crime detection and punishment varies from place to place and from time to time, but, at any given place and time, society is confronted with a fixed set of choices among the four harms, regardless of anybody’s views about their relative importance. By contrast, the weightings of the four harms – α, β, and γ – are a matter of individual taste, and may vary from one person to the next. This is especially evident for the parameter γ which is positive for people who place no weight on vengeance per se and who see punishment as a regrettable necessity, but negative for people who look upon punishment as desirable for its own sake. In fact, our designation of M, G, W, and C as four harms is inaccurate for people in the latter group who see G as a “good” rather than as a “bad.” People differ, though less radically, about α and β as well. Some see all violent death, from murder and from wrongful execution, as equally deplorable; for such people, α = β. Others have a special horror of mistaken execution, holding themselves in some sense

386 |

L A W |

responsible or fearing a general corruption of the state from the execution of the innocent; for such people β > α. Concern for the plight of the guilty may also differ markedly from one person to another.

Is there a natural law of murder that is sufficiently comprehensive and exact to rank execution and imprisonment? Can we speak unambiguously of one punishment or the other as the more conducive to the common good? It has been clear since chapter 1 that the appropriate law must be conditional on the technology of the economy and society. That was evident when patricide was seen as necessary, and therefore just, in some societies, though it is an abomination in others. The law of product safety and the law of murder have both changed radically in many countries over the last one hundred years. All that can reasonably be asked is whether there can be identified a “best” law in the service of the common good at any specific place and time.

As illustrated in the law of product liability, the efficiency criterion (the maximization of expected national income at invariant prices and with adjustments for changes in personal goods normally excluded from the measure of the national income) may, for some torts and crimes, be an adequate indicator of the common good. Behind the veil of ignorance, not knowing one’s place in society when the veil is lifted, and as likely to end up as defendant or plaintiff, one might as well opt for the maximization of the national income because whatever maximizes the national income must maximize one’s own expected income as well. Efficiency is a reasonable surrogate for the common good not just for the law of product liability, but for most commercial law.

A similar assessment can be made for the choice between imprisonment and execution as punishment for murder as long as the minimization of the number of murders is the overwhelmingly predominant consideration. The assessment changes fundamentally when the choice of punishment requires a balancing of the four harms together, for there is no legal analogue to market-determined prices by which different harms may be compared on a common, universally accepted scale. Just as people differ in the shapes of their indifference curves for amounts of bread and cheese, so too do they differ in their weightings of the four harms. People’s weightings may be conditioned to some extent by their circumstances in society, but, even behind the veil, some differences in weightings would normally persist. The veil of ignorance test corrects for people’s circumstances in society but not for their tastes. Thus, even behind the veil, there is no universally agreed upon best punishment, no punishment that everybody would choose as in his own interest when he is equally likely to occupy the station of each and every person in society: the law-abiding citizen fearing crime, the wrongfully accused, and the murderer himself. People with different weightings of the four harms are no more likely to agree on the best punishment for murder behind the veil than when the veil is lifted. It is hard to see how differences among people’s criteria for the law of murder can be reconciled, except politically when there is a general agreement to accept whatever a majority of voters and legislators decides.

Natural law remains as a goal or ideal. We would all like to think that there is a “best” law out there to be discovered, a law most conducive to the welfare of society as a whole, a law we would all agree to adopt if only we understood the full needs of society and the full technology of social interaction. Sometimes such law can be identified. Sometimes not.

L A W |

387 |

LAW AS A CONSTRAINT UPON THE LEGISLATURE AND

THE ADMINISTRATION

The analysis of voting in chapter 9 began with James Madison’s gloomy assertion in The Federal Papers that “democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security, or the rights of property; and have, in general, been as short in their lives, as they have been violent in their deaths.” Madison’s concerns were reflected in the exploitation problem in voting about the allocation of a sum of money among the voters themselves. No equilibrium emerged except with the connivance of a coalition of voters, the most likely coalition consisting of a bare majority prepared to take the entire sum for themselves and excluding the minority altogether. Strictly speaking, there is no telling within the formal analysis who the members of the majority coalition will be, but the formation of a majority coalition is facilitated by any pre-existing line of division among voters. Race, religion, ethnicity, location, and language may all serve as badges by which members of a majority coalition are identified. Badges need not be inherently divisive. They become divisive because democracy renders them profitable. The exploitation problem was not just that a majority exploits a minority, but that democracy self-destructs because nobody is prepared to accept the outcome of the vote peacefully. Chapter 9 then identified several defenses of democracy: natural defenses where voting is about matters not reducible to the allocation of a sum of money among voters, procedural defenses in the design of the voting mechanism, and institutional defenses – private property and civil rights – that enable society to avoiding voting about matters equivalent to the allocation of money among voters.

The discussion of civil rights in chapter 9 was brief and formal, almost as though, once enshrined in a constitution, civil rights could enforce themselves. In practice, the protection of civil rights must be assigned to a judiciary with some degree of independence from the legislature and the administration. Defense against exploitation of unpopular individuals or minority groups is the domain of public law, which may be divided into two branches: administrative law placing constraints on the discretion of the bureaucracy, and constitutional law placing constraints upon voters and legislators. A written or unwritten constitution is a defense of civil rights and a specification of the spheres of jurisdiction of the federal and provincial governments in those countries where the powers of lower levels of government are constitutionally entrenched. We consider these matters in turn.

Administrative discretion

A modern society needs a great deal of regulation. Public agencies decide when a person is qualified to become an immigrant, oversee standards of cleanliness in restaurants, check the safety of employment, run schools and hospitals, certify doctors and lawyers, and so on. Public agencies cannot do their job without a certain amount of discretion in their dealings with the public. Parliament can demand certification of doctors, but

388 |

L A W |

cannot specify in detail what skill is required, and must trust the certification board to discriminate between good doctors and bad, by examination or by watching candidates at work. Discretion cannot be unlimited, for administrators armed with unlimited discretion could victimize anybody, destroying the independence of the citizen required for the maintenance of democratic government. A few cases will illustrate what may be at stake.

Yick Wo v. Hopkins (US Supreme Court, 1886) was about the right to operate a laundry. Ostensibly as a fire regulation, an ordinance of the city of San Francisco required permission of the Board of Supervisors of the city to operate a laundry. Anybody operating a laundry without permission would be imprisoned. Yick Wo, who had been operating a laundry in San Francisco for twenty years in compliance with the earlier fire regulations, was said by the sheriff to be in violation of the new regulations and ordered to close his business. Yick Wo sued the sheriff. The suit eventually reached the Supreme Court. It was noted by the court that “all Chinese applications are, in fact, denied, and those of Caucasians granted,” from which it was inferred that the regulations “seem intended to confer, and actually do confer . . . naked and arbitrary power to give or withhold consent, not only as to places, but as to persons . . . depriving parties of their property without due process of law.” The Supreme Court sided with lower courts in pronouncing the San Francisco regulations to be in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment of the American Constitution, specifically of the clause: “Nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty or property without due process of law: nor deny any persons within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

United States v. Ju Toy (US Supreme Court, 1904) illustrates how extensive and how pernicious unconstrained administrative discretion can be. Ju Toy arrived at San Francisco on a ship from China. At that time, Chinese immigration to the United States (and to Canada as well) was prohibited. However, Ju Toy claimed to be an American citizen born in the United States and returning home from a trip to China. The immigration officers refused to believe him. A written appeal to the Secretary of Commerce and Labor was rejected. The case was appealed all the way up to the Supreme Court. The legal question in this case was whether there could be an appeal to ordinary courts of law from a determination by immigration officials with concurrence by the office of the Secretary of Commerce and Labour. A majority of the Supreme Court decreed that there could not, that the decision of the administration would be final and binding, that “due process of law does not require judicial trial” in this type of case. Leave aside the rights and wrongs of the ban on Chinese immigration. That was the law of the land at that time, however unjust it may appear to us today. The matter before the Supreme Court was the limit, if any, upon the authority of immigration officials to determine whether a person was native born. Dissenting from the verdict, a minority of the judges noted that the Act by which Ju Toy was being excluded placed the “burden of proof . . .

upon Chinese persons claiming the right of admission to the United States,” giving claimants very little opportunity to verify their claims and creating a state of affairs in which a “citizen of the United States must, by virtue of the ruling of a ministerial officer, be banished from the country of which he is a citizen.” A law banning immigration of Chinese could be converted by administrative discretion into a procedure

L A W |

389 |

for banishment of some native born Americans unless the courts were prepared to intervene, as they were not in this case. A spirited dissent by the minority judges did succeed in influencing the climate of opinion against excessive administrative discretion.

Flemming v. Nestor (US Supreme Court 1960) was about the citizen’s right to an old age pension. Ephram Nestor had immigrated to the United States in 1913 and was a member of the Communist Party from 1933 to 1939. From 1935 to 1955, Nestor and his employers contributed to the US government’s old age and survivors trust fund to provide him with an old age pension. In 1956, Nestor was deported for having been a communist, his old age pension was terminated and his wife in America was impoverished. The law under which Nestor was deported stipulated that a person not born in the United States, but a legal immigrant, could be banished if he had at any time been a member of the communist party, even at a time when membership itself was not against the law. It is strange that the Supreme Court tolerated a law banishing Nestor for an act which was not a crime when the act was committed, but that is not our concern here. Our concern is with the denial of the old age pension as an administrative decision. The Supreme Court upheld the administration in this case, on the peculiar ground that Nestor’s benefits were not an “accrued property right” and “cannot be soundly analogized to that of a holder of an annuity.” Once again, victimization of an individual by the administration could have been blocked by the courts, and was not.

Roncarelli v. Duplessis (Canadian Supreme Court, 1959) illustrates how an agency of government might destroy a person’s livelihood as unofficial punishment for adherence to an unpopular religion. Mr Roncarelli was the owner of a successful restaurant in Montreal and a member of the Witnesses of Jehovah. For some time, Witnesses of Jehovah had been arrested and tried for distributing their magazines, The Watch Tower and Awake, which were deemed insulting and offensive to the religious feelings of the general population. Mr Roncarelli did not distribute these magazines himself, but he provided bail for his coreligionists. The success of Mr Roncarelli’s restaurant depended on his having a permit to sell liquor. Permits were issued by the Liquor Commission which had the authority “to cancel any permit at its discretion.” On instructions from Mr Duplessis (who was at once the attorney general and the premier of the province), the administrator of the Liquor Commission cancelled Mr Roncarelli’s permit. Mr Roncarelli sued Mr Duplessis, and the case eventually reached the Canadian Supreme Court. The court found for Mr Roncarelli on the grounds that the government’s reasons for denying a permit “should unquestionably be such and only such as are incompatible with the purpose envisaged by the statute . . . There is no such thing as absolute and untrammelled ‘discretion,’ . . . for any reason that can be suggested to the mind of the administrator; no legislative act . . . can be taken to contemplate an unlimited arbitrary power, regardless of the nature or purpose of the statute.”

All of these cases may be seen as pertaining to the rule of law. We speak of the rule of law as “the absence of arbitrary power on the part of the government” and as a constraint on the society whereby “no man is punishable or can be lawfully made to suffer in body or goods except for a distinct breach of law established in the ordinary legal manner before the ordinary courts of the land.”

390 |

L A W |

The protection of civil rights

Though there is no watertight division between administrative law and the protection of civil rights, a rough and ready distinction can be drawn between trespassing on people’s rights by the administration in its interpretation of otherwise unobjectionable laws and trespassing on people’s rights by the legislature through laws that are inherently discriminatory or in violation of the written or unwritten constitution. The one pits the courts against the bureaucracy. The other pits the courts against the legislature.

The court’s willingness to strike down legislation as unconstitutionally discriminatory is dramatically illustrated by the contrast two famous cases, Plessy v. Ferguson (US Supreme Court, 1896) and Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (US Supreme Court, 1954). The first of these cases permitted the United States to segregate people by race; the second overturned the first. Plessy v. Ferguson was about segregation by race of passengers on railroads. The State of Louisiana assigned white and colored passengers to different coaches. Though seven-eighths white, Plessy was classified as colored and arrested when he insisted on riding in the coach reserved for whites. The Supreme Court denied that “the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority” and confirmed the decision of the lower courts to let the Louisiana law stand. Dissenting, a minority of the judges asserted instead that “everyone knows that the statute in question had its origin in the purpose, not so much to exclude white persons from railroad cars occupied by blacks, as to exclude colored people from coaches occupied by or assigned to white persons.” Over half a century was to pass before that decision was reversed in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. The case was about segregated schooling rather than travel, but the principle was much the same. The court decreed that “in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate facilities are inherently unequal.” It is interesting to speculate whether Brown was absolutely necessary, whether the massive change in the climate of opinion after the Second World War could have put an end to legal segregation by legislation without intervention by the judiciary. American federalism might have been an insuperable barrier. Segregation might have been abolished in some states but preserved in others indefinitely.

The constitutional entrenchment of property rights

The protection of private property could be, and to a large extent is, left to the good sense of the legislature. Legislatures can be presumed to understand the benefits of private property – prosperity and democracy itself – and to realize that to undermine private property is to lose almost everything of value in a modern industrial state. Property rights may, nevertheless, be more secure when constitutionally entrenched. A political party in office must resist the temptation to victimize or expropriate its opponents, to enrich its supporters and to preserve itself in office indefinitely. A political party is more likely to restrain itself today, the more certain it can be that the opposition party will be equally restrained tomorrow. A degree of constitutional entrenchment of property may help to provide that certainty. On the other hand, a comprehensive

L A W |

391 |

constitutional injunction against expropriation of private property may affect society in unintended and unfortunate ways.

A degree of constitutional protection is provided by the principle of just compensation. People can only be said to own property if they are reasonably sure the government will not arbitrarily take it away. The virtues of the institution of private property – the efficiency of the competitive economy and the economic conditions for government by majority rule – require not perfect security of tenure, but more security than there would be if the government of the day had no compunction about canceling one’s property rights as it sees fit. A school is to be built in my town. Somebody’s property has to be acquired and his house demolished to make way for the new school. Ideally, the municipal government would buy a property from a willing seller. That is not always possible because the owner of the only suitable site may not wish to sell or may try to hold the municipality to ransom. Purchase becomes especially difficult when many adjacent properties have to be acquired to make way for a road. If the municipality were empowered to take the property without compensation, everybody’s property would become insecure and the threat of expropriation could be used by the government in office to intimidate its opponents. If every property owner could hold out for a mutually acceptable price, schools and roads might become exorbitantly expensive. The rule within the common law is that the government may take private property but must compensate the owner according to the going market price. The Fifth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States includes the phrase, “nor shall private property be taken for public use without just compensation.”

The principle of just compensation can be widely or narrowly interpreted, and there has evolved a large body of law about the boundary between the taking of property for which compensation is mandatory and the exercise of the police power where people may be affected differently but no compensation is required. Consider the list of public policies with private consequences: My house is expropriated to make way for the construction of a school or a road. My land is flooded when an adjacent river is dammed. My business is ruined when the street on which it is located is converted from two-way to one-way. My distillery becomes valueless when the municipality imposes prohibition. My property loses much of its value because of the noise from a new airport nearby. A municipal ordinance forbids me to drain a swamp on my land for a housing project. An increase in the progressivity of the income tax reduces my net after-tax income if I am rich and increases my net income if I am poor. In all of these cases, public policy transfers income or property from one person or group to another. Some would argue that every one of these transfers is unconstitutional. Others would restrict compensation to the direct taking of tangible property. The courts have no choice but to sort the matter out case by case. Pennsylvania Central Transportation Co. v. New York City (US Supreme Court, 1958) was about Grand Central Station in New York. The City designated Grand Central Station a historical site, disallowing the construction of a very profitable skyscraper on the site. The owner of the property sued for compensation, claiming the loss of potential revenue to be a taking and arguing that it ought not to be penalized now for building a beautiful structure a hundred years ago. The court sided with the city that the designation of a building as a historical site, together with restrictions on alterations, is not a taking prohibited by the Fifth Amendment.