Usher Political Economy (Blackwell, 2003)

.pdf

302 |

V O T I N G |

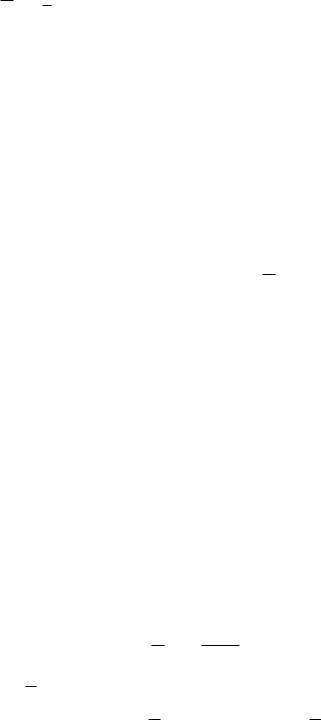

Table 9.6 The impact on voters of the redistribution of income in a community with three voters where taxable income may shrink in response to taxation

|

|

|

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

|

|

|

Post-tax, |

Post-tax, |

Post-tax, |

Total post-tax, |

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

post-transfer |

post-transfer |

post-transfer |

post-transfer |

Tax |

Total tax |

Tax revenue |

income of the |

income of the |

income of the |

income, |

rate |

revenue |

per person |

high-wage |

middle-wage |

low-wage |

(all three people) |

(%) |

($) |

(2)/3($) |

person ($) |

person ($) |

person ($) |

($) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

240.0 |

140.0 |

114.0 |

494 |

1 |

3.40 |

1.1 |

238.7 |

140.4 |

114.8 |

494 |

11 |

35.20 |

11.7 |

225.5 |

144.0 |

122.4 |

492 |

21 |

59.64 |

19.9 |

211.9 |

145.3 |

127.9 |

485 |

31 |

81.84 |

27.3 |

199.5 |

146.7 |

132.9 |

479 |

41 |

93.38 |

31.1 |

185.6 |

144.6 |

134.7 |

465 |

51 |

97.92 |

32.4 |

171.0 |

140.8 |

135.3 |

447 |

61 |

98.82 |

32.9 |

157.7 |

137.6 |

133.6 |

429 |

71 |

89.46 |

29.8 |

142.8 |

131.6 |

129.5 |

404 |

81 |

61.56 |

20.5 |

124.9 |

120.4 |

119.6 |

365 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

99.0 |

99.0 |

99.0 |

297 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

always pays more in tax than he gets back from the transfer. His personal interest is in having no redistribution at all. For the middle-wage person, the star appears at 31 percent. His post-tax post-transfer income is less at any lower or at any higher rate of tax. Recall that he is the person with the median wage ($10 per hour) which is less than the average wage ($12 per hour). As explained above, this discrepancy would lead him to favour a tax rate of 100 percent if all pre-tax incomes were invariant. But they are not invariant. The switch to do-it-yourself activities causes all taxable incomes to shrink as the tax rate increases, so that the middle-wage person is best off not at a tax rate of 100 percent, but at a tax rate of only 31 percent. The low-wage person would prefer a tax rate of 51 percent.

Note in passing that the relation between tax rate and tax revenue in column (3) of table 9.6 is similar to the relation between tax rate and tax revenue in table 4.1. In both tables, tax revenue begins at 0 when the tax rate is 0 percent, rises to a peak at some tax rate well short of 100 percent, and gradually falls to 0 again as the tax rate approaches 100 percent. In both tables, the relation between rate and revenue is hive-shaped because the tax base shrinks as the tax rate increases. In chapter 4, the tax base was the consumption of cheese in a bread-and-cheese economy where only cheese could be taxed. Here, the tax base is earned income where do-it-yourself activities cannot be taxed. The example in table 9.6 is generalized in the next chapter, and other similarities to the story in chapter 4 will be examined.

Since the middle-wage person is the median voter, his preference prevails. The electoral equilibrium tax rate is 31 percent, yielding a net transfer of $27.30 per person, causing a net loss of $40.50 to the high-wage person, a net gain of about $6.70 to the middle-wage person, a net gain of about $18.90 to the low-wage person, and a net reduction of $15 worth of goods and services [$494–$479] to the three

V O T I N G |

303 |

people together. Majority rule voting results in some redistribution of income, but not at confiscatory rates. The gap between rich and poor is narrowed, but not eliminated altogether. The rich remain relatively rich. The poor remain relatively poor. It is in nobody’s interest to close the gap completely.

Though the example is made up, the main conclusion extends, with qualifications, to more realistic environments. First, it was essential to the example that the average wage exceed the median wage, for, otherwise, the median voter would have opposed redistribution altogether. The median voter would have opposed all redistribution if, for example, the wages had been $20, $15, and $7 per hour instead of $20, $10, and $6 per hour as we assumed. With wages of $20, $15, and $7 per hour, the median wage is $15 an hour, the average wage is only $12 per hour, and the median voter is made worse off, not better off, by redistribution. But the assumption in the tables that the average wage exceeds the median wage is entirely realistic, a reflection of the fact that all income distributions ever observed have been skewed with a few rich and many poor.

Second, the flight from paid work to do-it-yourself activities is only one of several incentives generated by taxation. As the tax rate increases, people tend increasingly to divert time from work to leisure, to substitute barter for the market, to participate in the underground economy, and to employ lawyers and accountants to discover ingenious ways of minimizing their tax bill. All this tends to reinforce the story in our example of do-it-yourself activities that the pie shrinks as you share it, limiting the extent of sharing in the interest of the recipients of redistribution. A somewhat uncharacteristic feature of the example is that the alternative to earning taxable income is the same for everybody, rich and poor alike. Everybody is supposed to be equally adept at do-it-yourself activities. Other opportunities for reducing tax paid, notably legal tax avoidance, are likely to be more available to the rich than to the poor.

Third and most important, the redistribution of income, depicted here as the choice of a rate for a negative income tax, is in practice very much more complicated. There is no single rate of tax. Instead, there is a progression of tax rates, a basic exemption, a low rate on additional income up to some amount, a higher rate on the next chunk of income, and so on. There is no single source of income. Instead, there are different kinds of income – wages, dividends, rent, capital gains – each with its own tax rates and tax exemptions. There is no uniform transfer of income. Instead, the transfer is targeted in many programs including welfare to the demonstrably poor, unemployment insurance, the old age pension, and public provision of health and education financed by taxation but provided equally to everybody in the appropriate circumstances. It is nevertheless possible to make a crude assessment of the degree of redistribution in tax and expenditure together, and there is some counterpart in real politics to the median voter whose sense of the appropriate degree of redistribution is a basis for public choice among the possible redistributive programs. More will be said about this in the next chapter.

The ordered and self-limited redistribution in this example is in sharp contrast to the exploitation problem as discussed above under the general heading of the diseases of democracy. In the exploitation problem, voting about the allocation of income yielded no equilibrium or stopping place, and the impact of voting on people’s incomes was so dramatic – transporting people from very rich to very poor at the whim of the

304 |

V O T I N G |

electorate – that people would soon cease to respect the outcome of the vote or, in one last vote or by coup d’etat, would replace government by voting with some more stable form of government. By contrast, in the present example, there is a unique electorial equilibrium and the people’s incomes are less drastically affected by the outcome of the vote. The rich, though poorer, remain relatively rich. The poor, though richer, remain relatively poor.

The principal difference between the exploitation problem exemplified by voting about the allocation of $700,000 and the redistribution of income in our three-person example is that the transfer of income in the latter is systematic. Though people vote on the magnitude of redistribution (on the value of t), there is a prior agreement about the form of taxation that is completely absent in the specification of the exploitation problem. The ordering of incomes on the scale of rich and poor is taken off the agenda because people choose not to vote about it. In actual politics, voting is substantially less constrained, but is not unconstrained altogether. Democratic societies avoid ad hominem taxation. Though taxation may be redistributive, there is some respect for the principle of horizontal equity according to which people with equal incomes are to be equally taxed.

A variant of the anti-democratic argument, referred to by James Madison in the quotation at the beginning of this chapter, is that the poor cannot be entitled to vote because they would use the vote to expropriate the rich, removing the incentive to become rich or to invest one’s wealth productively and, in the end, impoverishing the nation as a whole. On this argument, property rights can only be maintained by restricting franchise to the well-to-do. Our example of redistribution in a three-person society suggests that universal franchise may have less dramatic consequences. To be sure, the poor do use the vote to expropriate the rich to some extent, narrowing the gap between the rich and the poor, but there is a natural stopping place to redistribution, a stopping place well short of 100 percent confiscation of wealth, where the median voter is content. There is an electoral equilibrium where the rich get to keep enough of their income to induce a substantial degree of enterprise and thrift. It may even be that improvements in accounting over the last century have made possible a self-limiting redistribution of income – through progressive taxation, welfare, the old age pension and other measures – as distinct from the free-for-all that might have been the outcome of universal franchise in years gone by when systemic redistribution was infeasible.

Procedural defenses

Procedural defenses of majority rule voting are subsidiary conventions about how voting is conducted. We do not just vote. We vote in context, and the context matters. Voting for bills in the legislature is conducted according to parliamentary procedure, a set of rules about when amendments are permitted, who may propose amendments, the order of voting once all amendments are on the table, the length of debate, and a host of other matters. Legislators may be chosen by plurality voting (the candidate with the most votes wins) in single-member constituencies, by proportional representation in multi-member constituencies, or by two-stage elections in which the two candidates with the most votes in the first round become the only candidates in the second. There

V O T I N G |

305 |

is inevitably some residue of the paradox of voting and the exploitation problem in any and every method of voting, but, as we shall see, the virulence of these diseases of voting can be reduced considerably.

James Madison himself placed considerable weight on the division of powers between the central government and the state government, among legislature, executive and judiciary within the central government, and between the Senate and the House of Representatives. The hope was that factions or coalitions of factions within one branch of government would be neutralized by other factions within other branches of government. If the agricultural interests come to dominate the Senate, then perhaps the manufacturing interests will come to dominate the House of Representatives. If assent of both houses is required for the passage of a bill, then competing factions in the two houses may give rise to a compromise that is not too bad for either faction or for the country as a whole. Outcomes are determined to some extent by the constellation of voters’ preferences, but not entirely so. Just as bargaining and deal-making supplement the price mechanism in guiding the economy, so too do bargaining and deal-making supplement the voting mechanism in public decisionmaking. It might even be said that actual democratic government is designed to be inefficient, to move slowly, and to frustrate a party in office with a clear vision of how society ought to be redesigned, curbing the power of factions or coalitions of factions to change society today in ways that cannot be reversed tomorrow.

To see how political outcomes can depend on subsidiary voting rules, consider a simple society without private property where three people, called A, B, and C, vote about the allocation of the national income, Y, among themselves2. An allocation of income, written as {yA , yB, yC}, is an assignment of incomes yA to person A, yB to person B, and yC to person C, where yA + yB + yC = Y. Voting about such an assignment collapsed into incoherence in the seven-person example above where all voters were free to propose amendments indefinitely. Suppose instead that there is a prior agreement among the three people that the voting will be conducted as follows:

Step 1

The three people draw lots to determine who among them may propose a bill specifying the allocation among themselves of a fixed national income, Y. The bill proposed by the winner of the draw is designated as {yA0 , yB0 , yC0 }. This bill is chosen to provide the proposer with the highest possible income, not immediately, but in the final outcome of the voting process.

Step 2

Once a bill {yA0 , yB0 , yC0 } has been proposed, there is automatically a vote on fast-track consideration. If fast-track consideration is approved, no amendment to the bill is allowed and voting proceeds to step 3. If fast-track consideration is denied, voting proceeds to step 4 where an amendment is allowed. Approval of fast-track consideration may require either unanimity or acceptance by a majority of the voters. It will be

306 |

V O T I N G |

shown below that the requirement has a marked influence upon the allocation of the national income among the three voters.

Step 3

There is a vote on the original bill. If a majority favors the bill, it becomes law and the allocation {yA0 , yB0 , yC0 } prevails. If a majority opposes the bill, it does not become law and voting proceeds to step 4.

Step 4

The three people draw lots once again to determine who among them may propose an amendment designated as {yAa , yBa , yCa }. If the author of the original bill wins the lottery to propose the amendment as well, he may, but need not, choose to repeat the original bill as an amendment. A vote is conducted between the original bill {yA0 , yB0 , yC0 } and the amendment {yAa , yBa , yCa }. The winner of that vote becomes law, and the allocation of income is determined accordingly. No additional amendments are allowed.

Voting always ends at step 3 or step 4. The outcome of voting at step 3 is either the original bill or a decision to permit an amendment. The outcome of voting at step 4 is either the original bill or the amendment. At both steps, voting is by majority rule, which, in a society of three people, means that whichever option is favored by two out of the three voters becomes law. The voting rule at stage 2 – on whether to grant fast-track consideration for the original bill – may be by majority rule or by unanimity. In fact, the entire point of the example is to show how the outcome of the voting process can be radically different depending how voting at stage 2 – on whether to grant fast-track consideration for the original bill – is conducted. One of the following two rules is adopted.

1Fast track consideration (proceeding to step 3) is only granted if approved by voters

unanimously.

2Fast track consideration is granted if approved by a majority, two out of three voters.

But for the special voting rules we have imposed, this situation would have all the hallmarks of a standard exploitation problem with no electoral equilibrium. From our discussion of the exploitation problem, we might expect a deal between two of the three people, providing each with half the income and excluding the third altogether. If the deal is between person A and person B, then the outcome becomes yA = yB = Y/2 and yC = 0. As long as the deal holds, any other outcome is voted down. We assume instead that there can be no deals among voters, that each voter behaves rationally and selfishly at each step of the voting procedure (an assumption that yielded no outcome when every proposal could be outvoted by some other

V O T I N G |

307 |

proposal put forward as an amendment) but that voting is circumscribed by strong procedures.

We also assume that everybody is somewhat risk averse. In a choice among gambles, each person acts to maximize his expected utility, where the utility of income, y, is assumed to be √y. For example, a person would be indifferent between an income of 4 for sure and equal chances of incomes of 1 and 9, even though the expected income associated with equal chances of incomes of 1 and 9 is 5 rather than 4. With

equal chances of incomes 1 and 9, a person’s expected income is 5, [ 1 (1) + 1 (9)],

√ √ 2 2

but his expected utility is 2, [ 1 1 + 1 9], while the utility of a sure income of 4 is

√ 2 2

also equal to 2, [ 4]. With these assumptions – no coalitions, pure selfishness and restricted voting – the outcome of voting becomes determinate.

Consider first what happens when voting about fast-track consideration is by majority rule. There is no harm in assuming that person A wins the draw to propose the original bill. The outcomes when B or C win are analogous. Person A would like to take the entire national income for himself, setting yA0 = Y, yB0 = 0 and yC0 = 0. The bill would be {Y, 0, 0}. He dare not propose that bill because it would surely lose the vote over fast-track consideration at stage 2, and person A would have a two-thirds chance of ending up with nothing at the end of stage 4. If, by chance, person A wins the draw to propose the amendment as well, he could acquire the national income by proposing an amendment that supplies a penny to person B, and nothing at all to person C. With the original bill as the alternative, persons A and B vote for the amendment at stage 4, and it becomes law. But if either person B or person C wins the draw to propose the amendment, he would propose an income of Y less a penny for himself, a penny for the other, and nothing for person A.

A better course for person A is to offer one of the other two people, say person B, enough income to induce him, in his own self-interest, to vote for fast-track consideration and then to support the original proposal at step 3. Person A’s original proposal becomes {Y − yB0 , yB0 , 0} where yB0 is just high enough to induce person B to vote as person A requires. How large must yB0 be? That depends on what person B anticipates in the event of an amendment. Person B compares the certainty of yB0 if he votes for fast-track consideration with equal chances of incomes yBaA , yBaB, and yBaC depending on who wins the draw to propose the amendment. If person A wins, his amendment provides a penny for person C, Y less a penny for himself, and nothing for person B. Thus, yBaA = 0. If person B wins, his amendment provides nothing for person A, a penny for person C, and Y less a penny for himself. Thus, since a penny is virtually nothing, yBaB = Y. If person C wins, his amendment provides nothing for person A, yB0 plus a penny for person B, and Y − yB0 less a penny for himself. Thus, yBaC = yB0 . The amendment always wins over the original proposal because the amendment is designed to provide the proposer of the amendment with the largest possible income consistent with one other person being better off with the amendment than with the original bill.

Pulling all this together, we see that person A’s original proposal contains the

smallest y0 |

such that |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

B |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

= 31 √ |

|

+ 31 √ |

|

+ 31 |

|

|

|

||

|

|

yB0 |

> 31 |

yBaA |

+ 31 |

|

yBaB |

+ 31 |

yBaC |

|

yB0 |

(8) |

|||||||

|

0 |

Y |

|||||||||||||||||

308 V O T I N G

√

Thus, 2 yB0 = Y or yB0 − Y/4. Person A’s original bill must be yA0 = 3Y/4, yB0 = Y/4,

and yC0 = 0. With majority rule voting on fast-track consideration, the fortunate person who wins the draw to make the original proposal gets to keep three-quarters of the income for himself, offers a quarter of total income to one of the other two persons and offers the remaining person nothing.

Now consider the other voting rule for the granting of fast-track consideration. Suppose fast-track consideration is denied unless the vote in favor is unanimous. If person A wins the draw for the right to propose a bill for the allocation of the national income among the three people, he must be more accommodating to persons B and C because either of them can force an amendment by voting against fast-track consideration. Person A’s bill must provide incomes of y0 to both person B and person C, leaving an income of Y − 2y0 for himself, where y0 must be large enough that nobody wants to vote against fast-track consideration.

Consider person B’s calculation of his options, bearing in mind that the circumstances of person C are identical. If person B approves fast-track consideration and on the understanding that the proposal will be adopted in the vote to follow, person B’s

income becomes y0 and his expected utility becomes y0. Alternatively, if fast-track consideration is denied, his expected utility depends on who wins the draw to propose the amendment. If person B wins, he proposes an amendment providing person C with y0 plus a penny, providing person A with nothing, and leaving an income of Y – (y0 plus a penny) for himself. If person C wins, his proposal is analogous, providing person B with y0 plus a penny, providing person A nothing and leaving Y – (y0 plus a penny) for himself. If person A wins, the calculation is a bit more complex. It would be in person A’s interest to cut out either person B or person C. Person A does not care which of the two is excluded, though he does not announce his decision prior to the vote on fast-track consideration for fear of antagonizing the excluded party. He flips a coin. If the coin comes up heads, he provides an income of y0 plus a penny to person B, and nothing to person C, leaving an income of Y – (y0 plus a penny) for himself. If the coin comes up tails, he substitutes person C for person B.

Thus, in the event of an amendment (and recognizing that a penny is virtually nothing) person B acquires a one-third chance of an income of Y − y0, a one-third chance of an income of y0, an additional one-sixth chance of an income of y0, and a one-sixth chance of an income of 0. Now person A’s original proposal contains the

smallest y0 such that |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

> 31 |

|

|

+ 31 |

|

|

+ 61 |

|

|

+ 61 √ |

|

|

|

y0 |

Y − y0 |

y0 |

y0 |

(9) |

||||||||||

0 |

||||||||||||||

It follows at once that |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

1 |

y0 = |

1 |

Y − y0 |

(10) |

2 |

3 |

so that y0 = ( 134 )Y. When the motion for fast track consideration of the original proposal requires unanimous assent, the proposer of the original motion offers each of the other two parties an income of 134 Y and takes an income of 135 Y for himself. It is still advantageous to win the draw to make the original proposal, but for less so than when fast-track consideration required only a majority of votes.

V O T I N G |

309 |

The moral of the story is that voting rules matter. On the critical assumption that everybody votes selfishly and with no side deals among voters, the outcome of the vote over the allocation of the national income is very skewed when fast-track consideration requires the assent of a majority of voters – 34 Y to one person, 14 Y to a second, and nothing to a third – but is almost equal when fast-track consideration requires unanimity. It must be borne in mind, however, that side deals are often feasible in practice and that the outcome of voting then depends critically on which group of voters comes together to vote as a block.

The reader should be wary of this example. Though instructive about how subsidiary rules can affect the outcome of the vote, the example is misleading in several respects. First, actual parliamentary procedure is very much more intricate than the voting rules in this example. In particular, the right to propose bills lies primarily with the party in office and not with randomly chosen legislators. At best, the rules about private members’ bills bear some resemblance to our example. Second, rules of actual parliamentary procedure are very much more elastic and more open to negotiation than our example would suggest. Third, there is an inextricable component of bargaining in parliamentary procedure. Though more nearly determinate than our discussion of the paradox of voting and of the exploitation problem would suggest, the outcome of voting is less determinate and the electoral equilibrium is less well grounded than one might infer from our example of voting procedures.

Institutional defenses

Procedural constraints on majority rule voting place restrictions upon how we vote. By contrast, institutional constraints place restrictions upon what we vote about. We do not vote about fining, imprisonment, disenfranchisement, or expropriation of particular people or groups of people because everybody – or a substantial majority of citizens – understands that he himself might be placed in jeopardy if such ad hominem voting were allowed. We do not vote about who owns what, in the sense of establishing a complete, brand-new allocation of property among citizens. We refrain from voting about people’s civil rights or property rights, and we protect these domains from the authority of the civil service. Civil rights are protected in a written or unwritten constitution that the great majority of citizens is prepared to respect and defend because the alternative is despotism or chaos. Property rights are protected in part by the constitution but primarily because of a general understanding that, without security of property, neither prosperity nor democracy itself could be sustained. These institutional constraints defend democracy by relying upon institutions other than voting, on the market and on the constitution, to resolve disputes that would prove dangerous and divisive in the hands of the legislature.

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms in the Canadian constitution and the Bill of Rights in the American constitution set bounds that no government, federal or state, can overstep without at the same time signaling to citizens and to public officials that loyalty toward one’s government, and obedience of inferior to superior within the government, may be dissolved. Among the provisions of the Bill of

310 |

V O T I N G |

Rights are that “Congress shall make no law respecting the establishment of religion,” that a person may not “be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law,” and that “private property shall (not) be taken for public use without just compensation.” The separation of church and state is to prevent a majority of one religion from using the authority of the government to impose that religion on others or to acquire special privileges for its adherents. “Due process of law” blocks the legislature, the courts and the administration from punishing a person – no matter how greatly they may disapprove of his actions and no matter how unpopular he may be – unless that person has actually broken the law. The prohibition of taking without compensation means that the legislature may not expropriate a person’s property, although it may take property with compensation as when a person’s land is in the path of a new road or is needed for a school. In such cases, the government may expropriate a person’s property but must compensate that person at market value. Similar constraints on voting are included in the constitutions of virtually every democratic country, though, as in the UK, the constraints may reside in the “unwritten” constitution rather than in an officially sanctioned text. Entrenchment of civil rights in a constitution cannot guarantee that civil rights will always be respected, but it increases the likelihood that civil rights will be respected by providing each citizen with an extra degree of assurance that his respect for civil rights, and for the constraints they impose upon political behavior, will be reciprocated by his fellow citizens.

Expectations play a major role in the institutional defense of democracy. The duly elected government today desists from the disenfranchisement of its opponents as long as the personnel of the government and their supporters among the electorate are confident that they themselves will not be disenfranchised tomorrow when they find themselves excluded from a new majority coalition. Were that not so, if I as a member of a majority coalition today expect to be disenfranchised when I am excluded from the new majority coalition tomorrow, then I had better abandon all restraint and entrench my privileges while I can. Nobody can be 100 percent confident that the constraints will always be respected, but constraints are more likely to be respected when entrenched in a constitution.

Another institutional defense is equally important. Democracy needs private ownership of the means of production. Recall the principal example in chapter 3 where five people – called A, B, C, D, and E – each owned land that could be used to make bread or to make cheese. In that economy, the production of bread and cheese, the return to each plot of land and the allocation of all produce among the five people were guided by prices in an impersonal market. A unique outcome emerged automatically, and that outcome was efficient as long as each person maximized his income at market clearing prices. A fundamental assumption in that example was that ownership was secure. No explanation was provided of how people acquired land or of how property rights were maintained. Secure ownership was simply taken for granted.

Now suppose these five people live in a civil society where public decisions are by majority rule voting and where, for the sake of the argument, there are no constraints whatsoever on what people may vote about. That being so, the five people might choose to hold all land collectively rather than privately. Collective ownership would constitute no violation of civil rights, but it is extremely unlikely that majority rule

V O T I N G |

311 |

voting could at the same time be maintained. Without private ownership of the means of production, a political mechanism would be required to determine how much bread and cheese to produce and, more importantly, how to allocate the produce among the five people. The allocation of the national income would have to be determined by voting. Allocation by voting would confront society with a standard exploitation problem. In such a society, there would be nothing to stop three out of the five voters from expropriating the land of the other two. It would be convenient, though by no means necessary, for the members of the majority coalition to have something in common. Three of the five people might differ from the other two by race, language, religion, or occupation. Any characteristic of voters might serve as a badge to distinguish the majority of the exploiters from the minority of the exploited. The minority might be disproportionally taxed, dispossessed of its land, disenfranchised, enslaved, or executed.

Why not? If people are unlimitedly greedy, as they are assumed in the study of economics to be, why should not a majority employ the vote to take the land of the minority? This question has been posed for centuries as an argument against democracy itself. The only answer would seem to be that voters desist from these extremes of predatory behavior for fear of destroying democratic government. No government in office would risk defeat at the ballot box, no temporary majority would risk the loss of its privileges in an election, and no political party, on losing an election, would accept defeat gracefully if the loss of an election meant the loss of one’s property or one’s life. Governments risk loss of office, their supporters risk loss of privileges and political parties accept defeat gracefully because the institution of voting is expected to persist, so that a person who finds himself in a minority today has a reasonable chance of finding himself in a majority in a new vote on a different issue tomorrow. The substitution of allocation by markets with allocations by voting automatically raises the stakes of an election beyond what citizens can tolerate and ultimately corrodes the electoral process.

Property protects voting by attending to a task that voting cannot perform. The moral of our discussion of the exploitation problem was that the national income cannot be allocated by voting because there is no unique electoral equilibrium allocation when each voter behaves selfishly and because the most likely form of cooperation in voting about the allocation of income is for some majority to vote as a block to dispossess the remaining minority. Understanding how voting works, citizens would cease to respect the rules. Sooner or later, a party in power would abolish voting rather than risk the privileges of office at the ballot box. A market mechanism based on private ownership of the means of production (including one’s own skill and labor power) circumvents the exploitation by placing the allocation of the national income among citizens outside the political arena.

Markets determine wages, rents, land prices, and returns to the ownership of capital, as well as prices of ordinary consumption goods, like bread and cheese. Formally, the price mechanism stops at the door of the public sector, so that wages of public servants have to be determined politically, but the market supplies a standard that the government may choose to respect, just as the incomes of the police could, but need not, be set to equal the incomes of fishermen in the model of predatory behavior