Nafziger Economic Development (4th ed)

.pdf676Part Five. Development Strategies

14.Is China a good role model for LDCs that wish a market socialist economy?

15.What is an input–output table? Of what value is input–output analysis to a planner? What are some of the weaknesses of the input–output table as a planning tool?

16.What policies can planners undertake to encourage the expansion of private sector production?

17.What advice would you give to the person in charge of development planning in a LDC with a large private sector?

18.Since the fall of communism in 1989–91, is there any role for governmental planning?

GUIDE TO READINGS

World Bank, World Development Report (2003i:133–56) discusses strengthening national coordination, governance, and the provision of public goods.

Lewis (1966) has useful suggestions for planning in a mixed and capitalist LDC. Chenery (1989b) on resource allocation in planning, Chenery (1989a) on country experience with planning, and Robinson (1989) on multisector models are survey articles.

Miernyk (1965) offers an elementary explanation of input–output analysis, and Thirwall (1977) and Kenessey (1978) provide concise applications to LDC planning. Heston (1994) critiques input–output data and national accounts in LDCs.

Sundrum (1987) looks at India’s growth and planning; Kornai (1987) focuses on Hungary’s socialist market economy; Schrenk (1987) examines the former Yugoslavia’s worker-managed socialism; and Gregory and Stuart (2001) analyze Soviet economic planning. Lange and Taylor (1965), Horvatˆ (1975), Vanek (1975), and Nove (1983) discuss market socialism.

Stewart (1985) responds to Lal’s (1983) critique of dirigisme. The contributors to Boettke (1994) present their views of The Collapse of Development Planning.

Coase (1937:368–405), Williamson (1981:137–168; 1967:123–139), and Williamson and Winter (1991), although focusing on the firm, have implications for the relative costs of monitoring and other transactions under the plan and the market.

Ayittey (2005) provides the most detailed documentation of post-independence misdirection, administrative ineptitude, and rural neglect by Africa’s political elites, resulting in widespread reduced well-being over the last 45 years. For him, Africa’s failure not only results from wars and AIDS but also the failure of agriculture, indicative of the contempt of predatory rulers for the peasants, that results from an emphasis on mechanization (not donkeys, horses, wooden carts, and bush paths), the exploitation of peasants through price disincentives, and widespread efforts at statism (socialism). Ayittey would rely less on modernizing elites and more on traditional chiefs whose rule he considers closer to that of bottom-up development.

Amsden (1989:80) indicates that the South Korean state instigated “every major shift in industrial diversification” in the 1960s and 1970s, including import substitution in cement, fertilizers, oil refining, and synthetic fibers. Over time, joint public-private ventures became more common.

678Part Five. Development Strategies

bank loans to middle-income countries (Wall Street Journal 1988:19; Mossberg 1988:1, 24).

After 1987, the World Bank group (including its soft-loan window, the International Development Association or IDA), the IMF (Structural Adjustment, later Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility), and bilateral donors concentrated the SPA on low-income debt-distressed sub-Saharan Africa. The SPA increased co-financing of adjustment with other donors, and provided greater debt relief, including cancellation of debt from aid and concessional rescheduling for commercial debt from creditor governments. Also, the Bank created a Debt Reduction Facility for the poorest debt-distressed countries in 1989 and joined the IMF in 1996 to set up the initiative for highly indebted poor countries (HIPCs) (Chapter 16).

International Monetary Fund

A balance of payments equilibrium refers to an international balance on the goods and services balance over the business cycle, with no undue inflation, unemployment, tariffs, and exchange controls. Countries with chronic balance-of-payments deficits eventually need to borrow abroad, often from the IMF as the lender of last resort. In practice, a member borrowing from the IMF, in excess of the reserve tranche, agrees to certain performance criteria, with emphasis on a long-run international balance and price stability. IMF standby arrangements assure members of the ability to borrow foreign exchange during a specified period up to a specified amount if they abide by the arrangement’s terms. IMF conditionality, a quid pro quo for borrowing, includes the borrower’s adopting adjustment policies to attain a viable payments position – a necessity for preserving the revolving nature of IMF resources. These policies may require that the government reduce budget deficits through increasing tax revenues and cutting back social spending, limiting credit creation, achieving market-clearing prices, liberalizing trade, devaluing currency, eliminating price controls, or restraining public-sector employment and wage rates. The Fund monitors domestic credit, the exchange rate, debt targets, and other policy instruments closely for effectiveness. Even though the quantitative significance of IMF loans for LDC external deficits has been small, the seal of approval of the IMF is required before the World Bank, regional development banks, bilateral and multilateral lenders, and commercial banks provide funds.

Policies generally shift internal relative prices from nontradable to tradable goods, promoting exports and “efficient” import substitution. Although policies generally move purchasing power from urban to rural areas, consumers to investors, and labor to capital, subgroups within these categories may be affected very differently; moreover, government functionaries who oversee and administer programs still possess discretion in distributing rewards and sanctions. Conditions attached to IMF credits sometimes provoke member discontent, as in Nigeria’s anti-structural adjustment “riots” in mid-1989.

The DCs’ collective vote, based on members quotas, is 68 percent. And LDCs often support DCs in laying down conditions for borrowers so as not to jeopardize

19. Stabilization, Adjustment, Reform, and Privatization |

679 |

the IMF’s financial base. Still, many African and Latin American borrowers say that IMF conditionality is excessively intrusive. Thus, for example, in 1988, in exchange for IMF lending to finance a shortfall in export earnings from cocoa, coffee, palm products, and peanuts, Togo relinquished much policy discretion, agreeing to reduce its fiscal deficit, to restrain current expenditures, to select investment projects more rigorously, to private some public enterprise, and to liberalize trade. Yet the IMF must be satisfied that a borrower can repay a loan. Lacking adjustment by surplus nations, there may be few alternatives to monetary and fiscal restrictions or domesticcurrency devaluation for eliminating a chronic balance-of-payments deficit (Nafziger 1993:101–102).

Critics from LDCs, supported by the Brandt Commission (see Chapter 15), charged that the IMF presumes that international payments problems can be solved only by reducing social programs, cutting subsidies, depreciating currency, and restructuring similar to Togo’s 1988 program. According to the Brandt report, the IMF’s insistence on drastic measures in short time periods imposes unnecessary burdens on lowincome countries that not only reduce basic-needs attainment but also occasionally lead to “IMF riots” and the downfall of governments. These critics prefer that the IMF concentrate on results rather than means (Independent Commission on International Development Issues 1980:215–216; Mills 1989:10).

Despite a decline in funds from the 1970s to the 1980s, the IMF maintained or even increased its leverage for enforcing conditions on borrowers in the 1980s, for during the 1980s and early 1990s, World Bank loans consolidated conditions set by the IMF. The IMF became gatekeeper and watchdog for the international financial system, as IMF standby approval served as a necessary condition for loans or aid by others. Moreover, the World Bank led donor coordination between DCs and the Bank and Fund, increasing their external leverage. Many low-income recipients, especially from Africa, lacked personnel, abdicating responsibility for coordinating external aid, and increasing the influence of the Bank, IMF, and other donors.1

Internal and External Balance

A country needs to adjust whenever it fails to attain balance of payments and domestic macroeconomic equilibria, that is, equilibra referring to both external and internal balances. The following is a simplified explanation of how to attain both external and internal balance.

1 Loxley (1986:96–103); Economic Commission for Africa (1985); Weeks (1989:57).

An example of skillfully playing the World Bank against the IMF for public relations gains involved President Ibrahim Babangida, who from 1985 to 1986 conducted a yearlong dialogue with the Nigerian public, resulting in a rejection of IMF terms for borrowing. The Babangida military government secured standby approval from the IMF but rejected its conditions, while agreeing to impose similar terms “on its own” approved by the Bank. In October 1986, the Bank, with Western commercial and central support, delivered $1,020 million in quickly disbursed loans and $4,280 million in three-year project loans (Nafziger 1993:130).

680 Part Five. Development Strategies

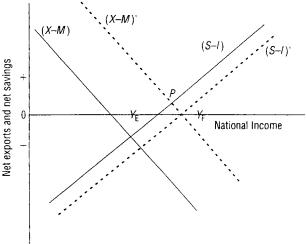

FIGURE 19-1. Internal and External Balances.

Remember national-income equation 15-5:

S = I + (X − M) |

(19-1) |

where S = Savings, I = domestic investment, X = exports of goods and services, and M = imports of goods and services.

If we subtract I from both sides of the equation, |

|

S − I = X − M |

(19-2) |

or savings minus investment equals the international balance on goods and services. Internal balance refers to full employment (and price stability); external balance refers to exports equal to imports. Figure 19-1, a simple model of Keynesian macroeconomic income determination, shows the relationships between income and expenditures and internal and external balances. Figure 19-1’s upward-sloping line shows net domestic savings, Savings (S) minus Investment (I). The downward-sloping line shows net exports, Exports (X) minus Imports (M). (Savings and imports depend on income; investment is dependent on the interest rate and the expected rate of return; and exports are dependent on foreign income.) The intersection of S − I with X − M indicates net savings and net exports on the vertical axis, and on the horizontal axis,

an equilibrium income (YE) short of the full-employment level of income (YF).

A simple algebraic manipulation changes our equation to the macroeconomic equilibrium where

S + M (leakages) = I + X (injections) |

(19-3) |

that is, aggregate demand equals aggregate supply, or expenditures equal income. Countries facing a persistent external deficit can (1) borrow overseas without

changing economic policies (feasible if the deficit is temporary), (2) increase trade restrictions and exchange controls, which reduce efficiency and may violate international rules but may be tolerated in LDCs, or (3) undertake contractionary monetary

19. Stabilization, Adjustment, Reform, and Privatization |

681 |

and fiscal policies or expenditure-reducing policies (a shift of the [S − I] curve upward and to the left), which sacrifice internal goals of employment and growth for external balance. Remedy (3), which critics call “leeching” after the 19th-century medical practice of using bloodsuckers to extract “unhealthy blood” from the sick, works with sufficient regularity to be considered the creditor community’s least-risk choice. An economy, if depressed sufficiently, will at some point reduce its balance-of- payments deficit. And indeed, World Bank evidence for 30 countries, 1980–85, indicates that LDCs undergoing adjustment gave up domestic employment and spending objectives to cut their payments deficit (Weeks 1989:61; World Bank 1988a:1–3). If the deficit is chronic, additional borrowing without policy change only postpones the need to adjust. When the World Bank or IMF requires improved external balance in the short run (two years or so), the agency may conditions its loan on

(4) expenditure switching, that is, switching spending from foreign to domestic sources, through devaluing local currencies. For long-term adjustment, the Bank or Fund prescribes supply-side adjustments through infrastructure, market development, institutional changes, price (including interest rate) reforms, reduced trade and payments controls, and technology inducement to improve efficiency and capacity to facilitate growth with external balance, but these changes take too much time for short-run adjustment.

Consider the intersection of (X − M) and (S − I) in Figure 19-1, corresponding to an external deficit with unemployment. To attain both external or internal balances, the country combines expenditure-switching (depreciating domestic currency) and expenditure-increasing (expansionary monetary and fiscal) policies.

Depreciating the currency – for example, increasing the shilling’s (domestic currency) price of the dollar from Sh15 = $1 to Sh20 = $1 – results in the country’s export prices falling in dollars. If the sums of the price elasticities of demand for exports plus imports are at least roughly equal to one, the country’s goods and services balance will improve. Thus, net exports (X − M) increase (say) to (X − M) , an international surplus. At the same time, the net export and net savings schedules intersect at a point further to the right (P), corresponding to higher income and employment, but still at less than full employment.

Increasing demand through reduced interest rates or a rising government budget deficit (higher government spending or lower tax rates), an expenditure-increasing policy, lowers net savings (S − I) to (S − I) . The new net savings and net export schedules intersect at a full employment level of income, YF, with a zero balance of goods and services balance, attaining both internal and external balances.

Critique of the World Bank and IMF Adjustment Programs

Many LDC critics feel the IMF focuses only on demand while ignoring productive capacity and long-term structural change. These critics argue that the preceding model of two balances shows the cost of using austerity programs – contractionary monetary and fiscal policies – prescribed by the IMF. Additionally, these governments object to the Fund’s market ideology and neglect of external determinants of stagnation and instability. Moreover, IMF austerity curtails programs to reduce poverty

19. Stabilization, Adjustment, Reform, and Privatization |

683 |

of cuts on social public expenditures; falling educational and training standards; rising malnutrition and health problems; and rising poverty levels and income inequalities. . . . Many African governments have had to effect substantial cuts in their public social expenditures such as education, health and other social services in order to release resources for debt service and reduce their budget deficits. From the point of view of long-term development, the reduction in public expenditures on education . . . necessitated by stabilization and structural investment programs, has meant a reversal of the process, initiated in the early 1960s, of heavy investment in human resources development. . . . Today, per capita expenditure on education in Africa is not only the lowest in the world but is also declining. . . . All indications are to the effect that structural adjustment programs are not achieving their objectives.

Indeed, ECA Executive Secretary Adebayo Adedeji (1989:21–25) argued that structural adjustment “has produced little enduring poverty alleviation and certain [of its] policies have worked against the poor.”

The ECA objected to the World Bank’s and IMF’s adjustment programs emphasizing deregulating prices, devaluing domestic currency, liberalizing trade and payments, promoting domestic savings, restricting money supply, reducing government spending, and privatizing production. These programs, ECA argued, fail in economies like those of Africa with a fragile and rigid production structure not responsive to market forces.

The ECA (1989:–iii, 26–46, 49–53) called for a holistic alternative to failed Bank and IMF structural adjustment programs, with an emphasis on increased growth and long-run capacity to adjust. Yet the ECA’s list of policy instruments, although ambitious, was short on specifics. But the ECA emphasized adjustment programs as primarily the responsibility of Africans, who may set up programs in partnership with outside agencies, rather than having these agencies do the formulating, designing, implementing, and monitoring.

A Political Economy of Stabilization and Adjustment

Economic stagnation, frequently accompanied by chronic international balance on goods and services deficits and growing external debts, intensifies the need for economic adjustment and stabilization. A persistent external disequilibrium has costs whether countries adjust or not. But nonadjustment has the greater cost; the longer the disequilibrium, the greater is the social damage and the more painful the adjustment. Countries such as Yugoslavia and Algeria, which failed to adjust, were more vulnerable to poverty, displacement, and even war. Woodward (1995) blames the Yugoslav conflict on the disintegration of government authority and breakdown of political and civil order from the inability to adjust to a market economy and democracy. Yugoslavia’s rapid growth during the 1960s and 1970s, fueled by foreign borrowing, was reversed by more than a decade of an external debt crisis amid declining terms of trade and global credit tightening, forcing austerity and declining living standards. In Algeria, the lack of adjustment, stabilization, and growth in the

684Part Five. Development Strategies

1980s strengthened Islamist party opposition, which recruited substantially among discontented unemployed young men for terrorism (Morrisson 2000).

More than a decade of slow growth, rising borrowing costs, reduced concessional aid, a mounting debt crisis, and the increased economic liberalism of donors, the IMF, and World Bank compelled LDC elites to change their strategies during the 1980s and 1990s. Widespread economic liberalization and adjustment provided chances for challenging existing elites, threatening their positions, and contributing to increased opportunistic rent-seeking and overt repression. And cuts in spending reduced the funds to distribute to clients, and required greater military and police support to remain in power.

Political elites in Africa and other LDCs faced increasing pressure from slow growth and international debt crises, as well as external pressure by donors and the Bretton Woods’ institutions to liberalize and privatize. Pressures to cut the size of the state, amid shrinking resources, put substantial constraints on the ability of elites, particularly in Africa, to reward and sanction political actors, contributing to greater political instability. These pressures and constraints make it more difficult to undertake coherent programs for macroeconomic stabilization and structural adjustment and to attract more foreign direct investment and aid.

Although stagnation, a current-account deficit, and inflation are components of a macroeconomic disequilibrium, IMF stabilization programs in LDCs focus on the last two components, while neglecting stagnation. In Chapter 14, we mentioned the study by Bruno and Easterly (1998) that shows no negative correlation between inflation and economic growth for inflation rates under 40 percent annually. Amid South Korea’s 1997 crisis, the IMF told “the Korean Central Bank . . . not only to be more independent but to focus exclusively on inflation, although Korea had not had a problem with inflation, and there was no reason to believe that mismanaged monetary policy had anything to do with the crisis,” according to Joseph Stiglitz (2002b:45). When he asked why, Stiglitz was shocked by the IMF team’s answer: “we always insist that countries have an independent central bank focusing on inflation.” Cramer and Weeks (2002:43–61) argue that the focus of IMF orthodox programs on inflation (often draconian monetary measures) is usually unnecessary, and that reviving growth should generally take precedence over monetary and fiscal orthodoxy.

Indeed, as long as the IMF continues its orthodox emphasis, one essential reform is to strengthen independent financial power within the world economy – independent of the IMF Good Housekeeping seal for stabilization programs required before the World Bank, OECD governments, or commercial banks will provide loans, debt writeoffs and writedowns, and concessional aid. For Cramer and Weeks, the “evidence [is] that adjustment did not stimulate recovery in [low-income countries] LICs.” The World Bank (1992b), in its overview of adjustment, identified growth as the “long-term objective” and discussed “moving from adjustment to growth.” Indeed, for the Bank, the aim of adjustment loans “is to support programs of policy and institutional change to modify the structure of an economy so that it can maintain its growth rates and the viability of its balance of payments” (ibid.).

19. Stabilization, Adjustment, Reform, and Privatization |

685 |

The poorest countries, primarily in sub-Saharan Africa, that are most vulnerable to political instability, would benefit from the expansion of funding from Japan, the European Union, or its member states, or from banks or regional development banks independent of two sides (the IMF and U.S. government) of the triangle of the Washington institutions’ lending and policy cartel.2 Official donors and lenders, with their emphasis on democratization, political stability, and socioeconomic development and their provision of project and humanitarian aid, have a broader agenda than the IMF’s priority on the balance of payments (or even the World Bank on development and adjustment). Thus, donors should not condition funds on the recipient country’s stabilization agreement with the IMF. Bilateral agencies (and the EU) need to be more active in designing and monitoring the programs they co-finance with the IMF and World Bank. In addition, the monitoring by bilaterals should be separate, or at least supplementary, to that of the Bank/Fund (Aguilar 1997).3

Empirical Evidence

IMF and World Bank adjustment programs seek to restore viability to the balance of payments and maintain it in an environment of price stability and sustainable rates of growth. How successful have these programs been?

Adjustment programs resulting in switching expenditures from foreign to domestic sources (usually through devaluation) are supposed to improve the external balance while increasing growth. A World Bank (1988a) study of 54 LDCs receiving adjustment lending during 1980–87 indicated that more than half of the recipients improved their current account; however, their average growth was slower than before despite being significantly higher in the short run (though no more sustained) than nonrecipients’. Also recipients’ export growth and import decline were faster than others’ were, although some recipients’ import reduction resulted from lack of foreign exchange. Moreover, although recipients’ social indicators were generally higher than others’ were, recipients’ calorie intake stagnated or declined during the 1980s, a trend worse than other LDCs experienced.

The World Bank also measured the net change in performance of countries receiving adjustment loans (ALs) in the three years before to the three years after receiving ALs and compared this change to countries not receiving these loans. Among low-income countries generally, current-account balances and debt-service ratios improved faster, growth was slower, and inflation faster among recipients than the comparison groups. Middle-income countries receiving ALs, however, had faster growth (though faster inflation) than the comparators. For both low-income and middle-income countries, the burden of adjustment fell heavily on investment.

2 The third side of the triangle is the World Bank (Nafziger 1993).

3Ehrenpreis (1997) indicates that the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency or Sida “is planning to integrate [program-aid] support more closely with the over-all country strategy planning of development cooperation.” Sida is to define criteria related to the policy reform process without, however, setting the same conditions as the World Bank or IMF.